Luck, Good and Bad

In Asia, the feathers of the peacock are considered auspicious and protective. However in the early part of the 20th-century in the West, it was considered very bad luck to keep them in the home.

One silly explanation for this superstition is that it was promoted intentionally to prevent people from eating this large, delicious member of the pheasant family. In that way, the bird would be protected from extinction, for many people thought it was rare -- a quintessential rara avis.

The reason for the superstition has more to do with the eye-like markings at the tips of the feathers which, around the Mediterranean, recall the dreaded "evil eye"-- the ever watchful and envious glance of the she-demon, Lilith. She was blamed for otherwise inexplicable deaths of infants, among other misfortunes.

Only partly as a result of this association with the evil eye was it believed that the flesh of the peacock is poisonous. But in any case, that is nonsense.

At the height of both the Greek and Roman cultures, the bird was served at formal dinners with its feathers cunningly pasted back on, possibly with a honey mixture used as glue, so that the dramatic beauty concealed the roasted fowl. At the excessive and luxurious banquets of European kings and queens of the Renaissance, there was an epicurean delight consisting of stuffed roast birds one inside the other like the famous Russian wooden mamushka dolls. The outermost shell was the glorious peacock, its many-eyed train stretching the length of the middle of the "groaning board."

As Margaret Visser, in Much Depends On Dinner points out: People have always thought that what looks amazing must certainly taste wonderful, too.

From the time of Cicero until the Renaissance, no truly sumptuous European feast was held without a dish of peacock, often adorned with the bird's feathered head and fan of tail feathers. (A dish of swan could also be similarly displayed, the impressive wings taking pride of place instead of the fan.) According to "Food fashions of the Renaissance" in Food: The History of Taste, where you can see illustrations of tables set with these extravagant dishes, it was the rapid rise in popularity of the meat of the North American turkey that ended the reign of "peacock supreme."

Deities and Royalty

The peacock was associated with the Middle Eastern deity, Tammuz, consort of the goddess, Anat. In Greece, it was sacred to Hera, queen of heaven and lawful wife of Zeus -- a pair of them drew her chariot --, and they were kept at her temples. In the Roman Empire, peacocks were Juno's birds and on coins symbolized the females of the ruling houses, the lineage princesses.

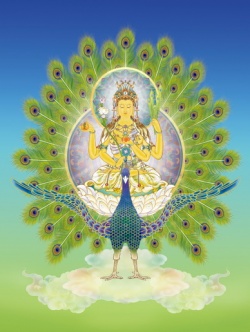

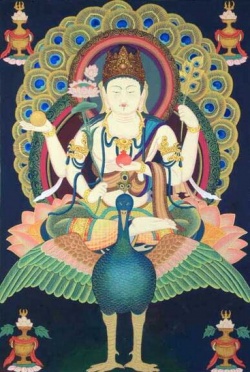

In both the Hindu and the Buddhist traditions, the peacock's influence is mainly in the realm of worldly appearance. (This is in contrast to the swan which is a symbol of the higher realms. ) Hence, the Mother-of-Buddhas, Mahamayuri-vidyarajni (Skt.) has a peacock as her vehicle. In Japan, she appears as Kujaku.

Skanda (also called Murugan,) one of the two sons of Indian god, Shiva, has a peacock for his mount. Lord of the elements of form, he is also a war god.

A standard made of peacock feathers used to indicate the presence of a 19th-century rajah, whose power is worldly.

In the old Chinese bureaucratic system, members of the third highest level displayed a peacock as the insignia of rank. These badges were in the form of large embroidered squares applied to the front of an official's formal gown. (A similar system for indicating status was used in the Byzantine Empire.)

Peacocks are considered sacred in India, especially in the north where its feathers may be burnt to ward off disease, and even to cure snakebite.

In a Buddhist tale about the travels of some Indian merchants to Baveru or Babylon, we learn that the inhabitants of that great city marvelled at the gorgeous bird which the merchants had brought with them.

The motif of two peacocks, one on each side of the Tree of Life, is a well-known feature of Persian decorative arts. A pair of peacocks stands for the "psychic duality of man" similar to the role played by the Gemini in western astrology, says Cirlot (A Dictionary of Symbols.) However it must be said that the notion of two natures -- in man or in the world that surrounds him -- is certainly not a universal one.

Because of that, in the iconography of European alchemy and hermaneutics, the peacock represents the soul. In Christianity, it stands for immortality and the incorruptibility of the soul, as in this XIth-century Byzantine image. It is an obvious solar symbol, too, because of the resemblance between the rays of the sun and the circular fan of the tail in full display.

"The Birds in Alchemy" by Adam McLean

J.E. Cirlot points out that in the Ars Symbolica of Hieronymus Bosch this blue-green bird represents the blending of all the colours of the spectrum (rainbow) and hence, the idea of totality. Tibetan culture among many others also views green as the mixture of all hues.

Among the Muslims of Java in Indonesia there is a myth about how the peacock guarding the gates to Paradise ate the devil, and that is how he managed to get inside. This myth makes a unity of the duality of good and evil, and also explains the bird's mysterious iridescent colour. It also incorporates the Indian notion of the incorruptibility of the peacock.

Purification

As we have seen, in the Hindu tradition the peacock is the vehicle [Skt.: vahana) of, or animal associated with, Kartikkeya, a.k.a. Skanda the 6-armed, 6-headed god of war who is a son of Lord Shiva. Kumari (Skanda/Subrahamanya's shakti) rides a peacock in the retinue of the Goddess Durga. Its [Latin] scientific name, pavo, derives from a Sanskrit epithet, Pavana (purity) that refers to the Hindu deity Vayu, the wind who is also the breath of life and the father of the hero Rama's friend, Hanuman.

It is said that at the time of Creation of the universe, when the primordial poison was churned out of the Sea of Milk and transmuted into the amrita of immortality, it was a peacock that absorbed the negative effects. Thus the bird is thought of as a protector, though its flesh is consequently considered to be poisonous.

Since a potentially deadly emotion such as anger is depicted as a serpent, and the peacock is immune, the peacock also symbolizes victory over poisonous tendencies in sentient beings. Hence the title of a well-known text for training the mind, Peacock in the Poison Grove by Dharmarakshita, a Tibetan classic in translation.

In the discourse, The Wheel of Sharp Weapons, another Buddhist treatise by Dharmarakshita, the peacock is credited with an ability to neutralize and use black aconite (aconitum ferox) as a nutriment. This highly toxic plant, also known as “'wolf-bane,” is an important ingredient in traditional Asian medicine including that of Tibet. Mixed with other ingredients, it was used in treatments for mental illness, among other complaints.

Goldenglow

Long ago, Brahmadutta was king of Benares, and he had wealth, treasure and possessions galore. He also had a most beautiful and elegant wife with a face that was lovely beyond compare, and her name was Peerless. This noblewoman was especially dear to the King, and he gladly satisfied her every whim.

At the time, on the southern slope of Kâilâsh, king of mountains, there lived a peacock whose name was Goldenglow, and he ruled a flock of five hundred followers. His limbs and body gleamed and his beak was like a jewel. Everywhere he went, he was acknowledged the grandest of all the peacocks.

One night, within the city of Benares, the call of the peacock-king rang out in the middle of the night and the following day, every one in the city was talking about it. The wife of Brahmadutta happened to be on the her terrace that night, so she asked the king, "Sire, whose stirring and mellifluous voice was that, last night?"

The King answered, "Princess, though I have never seen him, from its remarkable qualities, that voice must belong to Goldenglow, king of the peacocks, who lives on the southern slope of Kâilâsh.

Then the Queen said, "Sire, please have the king of peacocks brought here." The King replied, "But what good is it to see him going through the air?"

But the Queen said, "Sire, if you do not let me see this Suvar.naprabhâsa, I shall surely die."

So the King, who was very much in love with her, gave in saying, "All right, I will send for my huntsmen and fowlers." This he did, and he said to them, "They say that on the southern slope of Kâilâsh, chief of mountains, lives the peacock king, Suvarnaprabhâsa, whose limbs and body are glossy, and whose bill is like a jewel. Go, net or snare him, and bring him back. If you succeed, fine. But if you fail, I will have all of you put to death."

So the hunters and fowlers, in fear of losing their lives, took up their nets and snares and started off for Kâilâsh's southern slope. When they arrived at their destination, they set up their nets and set their traps all over the peacock- king's terrain, but though they waited seven days, they couldn't catch him, and they were all out of provisions, and very hungry.

Finally, out of compassion for them, the king of peacocks appeared and said, "You are hunters. Why do you stay here in this one place when you are starving?"

They replied, "This is the reason, Peacock-king: King Brahmadutta given us orders to 'Go, and with your nets and snares, catch me Suvarna-prabhâsa, the peacock king, whose limbs and body are glossy, whose bill is like a jewel, and who lives with five hundred followers on the southern slope of Kâilâsh, chief of mountains. If you bring him here, well and good, but if you do not, you shall all be put to death;' so in fear of our lives, we have come to try and capture you."

The king of peacocks responded, "Violent Ones, I cannot be taken by means of snares and nets, but if the King of Benares wants to see me, let him have the city swept, sprinkled with scented water, and decorated with flowers. And let him raise white awnings and banners, and burn incense. Let him prepare chariots bedecked with the seven jewels, and then, if in seven days he arrives in the company of his

entire army, I will go back to Benares with him, of my own free will."

So the hunters packed up their nets and snares, and returned to the King and told him everything that had happened, and what Suvarnaprabhâsa had proposed.

King Brahmadatta decided to take the King Peacock up on his offer, and he had the city of Benares prepared as the bird had instructed and then, his chariots ornamented with the seven kinds of precious stones, and surrounded by his cohorts he went off to the southern slope of Kâilâsh, chief of mountains.

The king of the peacocks, Suvarnaprabhâsa, also riding in a chariot decked with seven kinds of precious stones, uttered a cry which was heard by the whole army. King Brahmadatta was thrilled, and such joy filled his heart that he felt impelled to do homage to the bird. He prostrated to him and made offerings; and honouring him, they all went back together to Benares.

When they arrived at the town gates, the peacock again uttered his cry, and it was heard throughout the whole city. From all quarters, men, women, boys and girls all rushed to the gates. Then King Brahmadatta again honoured the peacock king, paying homage, making offerings, and bowing to him.

Once at the palace, he went to get the queen, and said to her, "Princess, the king of the peacocks, Suvarnaprabhâsa, has arrived at your dwelling."

Now King Brahmadatta had undertaken to make daily offerings of fruits and flowers to the great Peacock, but it so happened that there came a day that the King was very busy, and so he thought, "Who can make the proper offerings to Suvarnaprabhâsa?" and it occurred to him that Princess Peerless was both knowledgeable and skillful, and that she could certainly do it.

So King Brahmadatta sent for her and said, "Princess, please make the offerings to the king of the peacocks exactly as I have done," and the King's consort did so.

Time passed, and it so happened that the peerless queen had an affair and found out that she was pregnant. She realized that if she did not want the King to find out her adultery and have her put to death, she would have to silence the bird. So this

woman tried to poison the king of the peacocks by feeding him poisoned food and drink, but the more she gave him, the healthier he appeared -- he became even more lovely and resplendent, and the Queen was amazed.

Then Suvarnaprabhâsa called out, "Shame, shame on you! I know your kind. Because you are carrying another man's child, and this bird knows about it , you think that you can poison me so that the King will not find out from me and put you to death. But you never kill me with poison!

On hearing that, the Queen fainted and lost a great deal of bright blood. She wasted away, and when she finally died, she was born in hell.

"The King of Benares is now Shariputra, and I (Buddha) was Goldenglow, king of the peacocks."

~ Edited from the "Shariputra Sutra" as translated by Wm. Woodville Rockhill (1897.)

Protector and Preserver

One of Green Tara's many epithets is The Peahen ( Skt. Mayuri.)

Mahamayuri is green with 8 arms and 3 heads. Her faces are white, green and blue. Her eight hands display: Right side -- varadamudra, a sword, vajra and jewel; left side -- a bowl, a treasure jar, a bell and a flower. Seated on a lotus throne, she wears all the ornaments and celestial garments of a bodhisattva.

According to the Mahamayuri Sutra of Pancharaksha, there was a bhikshu in the Buddha's sangha called Svati, who was newly ordained. He was unfortunately bitten by a poisonous snake and fainted. Seeing his condition, Ananda reported this incident to Buddha Shakyamuni. Out of compassion for the newly ordained monk and for the future ones, Lord Buddha disclosed a dharani capable of eliminating poisonous harm and malignant diseases. This is the dharani of Arya Mahamayuri.

Maha-Mayuri became in Japan, a male figure called Kujaku Myo-o. This Buddhist wisdom deity associated with the peacock (whose call is believed to herald the rain) protects against calamity, especially drought.

Palden Lhamo, (pron. Penden Hamo, Skt. Shri Devi) the dark blue protector of all Tibetan Buddhist denominations who rides her mule through a burning [with wisdom) sea of blood (life in bodily form) is sheltered by a peacock-feather umbrella.

Lakshmi, wife of the Hindu god, Vishnu, sometimes is depicted with armbands in the form of peacocks. The birds are sacred to her since their cries are associated with the rainy season and hence, fertility.

The hero of the Indian epic, Mahabharat is called Arjun, a name that refers to the peacock. Also, there is a north Indian/Nepali deity called Janguli who protects against snakebite and poisoning. Described as having 3 faces, 6 arms, her vehicle is, not surprisingly, a peacock.

In Nepal, practitioners of Jhankrism, a shamanic tradition pre-dating both Buddhism and Hinduism, wear a tall head-dress of peacock feathers as an essential part of their regalia. Also notice the type of drum that is typical among shamans.

The peacock's beautiful and distinctive colouring is said to be a gift from the god, Indra. One day the King of Gods was doing battle with Ravana, the Demon King. The peacock, which in those days resembled his plain brown hen, took pity on Indra and raised its tail to form a blind or screen behind which Indra could hide himself. As a reward for this act of compassion, the bird was honored with the jewel-like blue-green plumage that it bears to this day.

Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu who is God-as-the-one-responding -to-devotion, is also depicted in the company of peacocks. One of Krishna's roles is as the irresistible divine suitor. Perhaps that is the link to the recommendation in The Kama Sutra that, if a man wishes to appear attractive to others, he can wear a peacock's bone covered in gold tied to his right hand.

Amitabha

The association of this jewel-tone bird with its sun-like fan of a tail evocative of the Wheel of Dharma -- the Buddha's teachings; its connection to the ideas of immortality and compassion, and the unification of views or opposites, as well as the correspondence with the Garden which is the Pure Land, demonstrates in Mahayana Buddhism the archetypical nature of the relationship between the peacock and Amitabha.

In the depiction of this Buddha of Eternal Light, he is seated under a tree; we see its flowers and leaves peeking through the pavilion. Tenga Rinpoche says, " . . . birds, in particular, have strong desire and craving, so, as a symbol of craving transformed into discriminating wisdom, Amitabha's throne is supported by peacocks."

There are actually eight peacocks that support his throne, one at each corner of the base. They stand for the idea that no matter the misdeeds committed during one's lifetime[s], rebirth is possible in Sukhavati, the Pure Land of Great Bliss that is the Western Paradise of Opameh (Tibetan for Amitabha). Any and all evil-doing is eventually absorbed.

Six peacock feathers arranged as a fan ornament the vase (bumpa) and sprinkling utensil used for distributing the blessing or purifying water in Tibetan Buddhist empowerments and other rituals. In this role they are not only a symbol of compassion, but also a symbol of immortality by virtue of their capacity to absorb and neutralize, and to act as a universal antidote against poisons including the kleshas [imperfections or obscurations) such as anger, greed and ignorance that are inherently human.

Natural History

The peacock is the male of a variety of the pheasant species, pavo cristatus. The female is a peahen; both are known as peafowl. It is native to India and Shri Lanka. A green variety, p. muticus, is found in neighbouring countries of south Asia. The Phoenicians introduced the peafowl to the pharaohs of Egypt, then it made its way to Europe among the spoils of Alexander of Macedon's returning army.

Each mature male may keep a harem of around 5 hens which it wins in fierce competition with other males. Screeching, preening, displaying [strutting and raising and lowering the "fan"] and a vigorous rustling of the tail-feathers are some elements in the courtship competitions. After the mating, the female lays a clutch of 4 to 6 spotted eggs in a hidden nest.

Peafowl spend most of the day on the ground pecking for food but as evening falls, they roost in the trees. In the spring, and when disturbed, the male can produce a sound very like that of a diesel truck's air horn. These birds are fairly intelligent, and can be trained to come when called. They are very hardy, adapting to fairly extreme temperatures. They are sometimes kept on estates not only as decorative birds, but as reliable "watchdogs."

3rd domestic bird on page is the peafowl. Hear its usual cry.

The peacock flies beautifully, but requires at least a 5-metre "runway" in order to get the lift required for take off. A surreal sequence of a white peacock in flight through lightly falling snow at the beginning of the 1973 Fellini film Amarcord is reason alone to get the dvd.

Two important writers who featured the peacock are Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964) who knew them well, and Raymond Carver (1938-1988) in Feathers.

___________________________________________________________________

Treasure pot: Buried or kept to attract prosperity or otherwise benefit a dwelling. Read about the Peace Vase Project for the types of contents.

rara avis: A Latin expression used to emphasize, often ironically, the exotic singularity of an individual. Of course the peacock is not rare at all and should not be confused with Birds of Paradise, the paradisidae species that are rapidly disappearing from New Guinea due to loss of habitat as well as the demand for gorgeous feathers.

Dharmarakshita: Known as Serlingpa in Tibetan, for having come from Sumatra, "the land of gold," he was Atisha's teacher (11th century.) He is the author of Wheel of Sharp Weapons. An earlier monk (ca. 261 BCE) of that name, who some say was a Greek, was invited to India by King Ashoka.

Goldenglow: Skt. Suvarnaprabhasa or Suparna, for short. Rockhill calls him "Golden-Sheen."

At the time of the Churning: An alternate view is that Lord Shiva's throat is dark because it was He who drank the poison, thus his epithet, Neelakantha. Shiva is also Mahakala, meaning both "Great Dark One" and "Great Time," the embodiment of Impermanence.