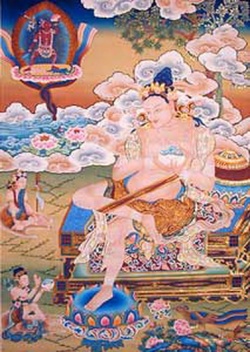

Mahasiddha Sri Naropa

Naropa was born into a noble family of Pullahari, in Kashmir, in 1016 AD. We are told that he was originally named Samantabhadra. He was raised as an aristocrat, with the intention that he would inherit the position of his father as a major ruler and leader of the people. However, by the age of eight his inclination was towards religion. He began to explore the field of learning and became a noted young scholar. Then, according to the well established customs of India, his parents arranged a marriage for him with a lovely Brahmin girl named Vimaladipe. Although the couple were happy together, Naropa's inner desire to pursue a religious course more and more began to dominate their lives. Vimaladipe became his disciple in this pursuit.

According to the story of Naropa's life, he deserted home and went to the main monastery of Kashmir for ordination. There he was ordained as a novice monk (sramanera) in the Sarvastivada order of Buddhism and engaged himself in scholastic studies for the next three years. Kashmir, at this time in history, was famous as a place of great learning and science.

At the age of 28, now a fully ordained monk (bhikkshu), Naropa graduated to Nalanda University in the heart of India. This state-sponsored University was an extremely famous place, with a faculty of 500 professors and a vast number of students, many from as far away as Ceylon, Indonesia, or even Greece and China. In those days nobody was considered truly learned unless they had studied at Nalanda University. The curriculum consisted of a ten year course and was extremely tough.

Nalanda had four grand gate houses leading into the University, and it was the privilege of the four most learned and highly respected professors of the University each to reside in one of these special houses. With time, Naropa rose through the ranks and eventually became one of these four professors. At this time in his life he was known as Mahapandita Abhayakirti. His fame spread far and wide, and for eight years he taught at this great institution of learning.

One day, so it is said, when Naropa was sitting in the shade of a large banyan tree, studying his books, an ugly old woman come up to him. She asked him if he could understand the words which he was reading. "Yes, of course," he replied, thinking that she was just some old illiterate peasant woman. At this she cackled with laughter. Then she asked him if he experienced the meaning of what he was reading. Again, he replied, "Of course." The old hag burst into tears.

"Why do you cry?" Naropa asked. She then explained to him that first she was overjoyed when he said he could comprehend the words, but she wept when he also claimed to really know the meaning. "You, having not experienced Enlightenment, cannot possibly really know the actual meaning," she explained. "Yet, being a scholar, you mistakenly believe that intellectual comprehension equals genuine Enlightened experience." Naropa had to admit that she was correct.

"How can I realize Enlightenment," he asked. "My brother is the great yogi Tilopa," she explained, "and he can guide you on the path of direct mystical experience."

As with many tales in the lives of an initiate, the legend of Naropa describes how he went through twelve painful trials, to receive the mystical teachings of the "Way of the Yogi" from Tilopa. Each trial that Naropa had to undergo demonstrated some aspect of the teaching and also broke through Naropa's pride. Though he suffered tremendously during these trials, Naropa persevered to the end and won through to Enlightenment in only a few years. By now, Naropa had renounced the life of a monk and become a white clad yogi in Tilopa's tradition. He wandered through Bengal.

After his Enlightenment, Naropa returned to Pullahari. It is said that his former wife became a great Yogini there, while following Naropa's guidance. She is famous as the Yogini Niguma and in many treatises is referred to as Naropa's sister. A lineage of instruction has come down from her to this day.

Naropa is renowned as the teacher of the Tibetan mystic, Marpa of Lhodrak. When Marpa, as a young man, first left Tibet, he traveled over the high passes to Parphing, in Nepal. He stayed at Parphing for some time, adjusting to the climate, prior to traveling down into the hot plains of India. It was while at Parphing that he met two Yogi brothers, both disciples of Naropa. This led to Marpa eventually seeking out Naropa and becoming his disciple. This is how the Tibetan Ka'gyu lineage began.

Marpa received the full Four Transmissions of Oral Instructions of Tilopa from his guru, and also gathered further instructions in Dream Yoga and the After-death state. This has come down to us as the Six Doctrines of Naropa.

Naropa came from Pataliputra, of mixed-caste parentage. His father was a liquor seller, but when the time came to follow his father's profession, Naropa rejected it and went into the forest to become a wood gatherer. Even there his restless, seeking soul gave him no rest.

One evening he chanced to hear tales of the great sage Tilopa. Then and there he decided that Tilopa was his guru and he would not rest until he had found him. The next day he traded a load of wood to a hunter for the yogin's traditional deerskin and set off toward Visnunagar in search of his master.

When he reached his destination he was dismayed to learn that the great sage had recently left and no one knew where he might be. Undaunted, Naropa set off on a journey that was to last for years and take him the length and breadth of India, as he followed every hint, every whisper of where Tilopa might be.

One day, when the dust sat heavy in the windless air, Naropa was on the road to nowhere in particular when he chanced to see a figure approaching in the hazy distance. For no discernible reason, his heart leaped in his throat. As if they had a mind of their own, his feet flew down the road toward the as yet unrecognizable figure.

But the closer he came the surer he grew. And finally, when he could make out the face and form of the other traveler, he knew. He had found Tilopa at last. He flew to the master's side, prostrated himself in the dust at his feet, then began dancing circles about him addressing him as "guru", and inquiring after his health.

Tilopa stopped still in the middle of the road, fixed Naropa with an angry stare and shouted: "Stop all this nonsense. I am not your guru. You are not my disciple. I have never seen you before and hope never to lay eyes on you again!" Then he thrashed Naropa soundly with his stout walking stick and told him to get out of his way.

But Naropa was neither surprised nor discouraged. Now that he had found the master he had sought for so many years, his faith was certainly not going to be shaken by a few blows. He simply set off for the nearest town to beg food for them both.

When he returned, Tilopa ate heartily without so much as a word of greeting and beat him soundly once again. Silent, Naropa contented himself with the leftover scraps, and once again walked around and around his guru in reverential circles.

For twelve long years he remained by Tilopa's side, begging food and serving him in all things. Not once did he receive a kind word. Not once did Tilopa acknowledge him as his pupil. And not once did Naropa's faith waver.

Toward the end of the twelfth year they chanced upon a village celebrating the wedding feast of a wealthy man's daughter. The generous host had provided the guests with eighty-four different types of curry. One of the dishes was a delicacy so rare and so exquisite that one taste would make you believe you had dined with the gods.

Naropa was given large helpings of all the curries, including the great delicacy. When he returned to Tilopa and spread out the feast, an amazing thing happened. For the first time in all the years Naropa had known him, Tilopa smiled. Then he helped himself to every morsel of the special dish. Licking his fingers, he handed Naropa his empty bowl, asking, "Where did you find this, my son? Please return and fetch me some more."

"'My son!' He called me 'my son!'" thought Naropa, happy as a Bodhisattva on the first level of the path. "For twelve years I have sat at my guru's feet without so much as being asked my name. And now he has called me 'my son!'" Floating in ecstasy, he returned to the wedding feast to ask for more of the special curry for his master.

But such was Tilopa's appetite that he sent his disciple back again and again. Each time, to Naropa's great relief, he was given more of the elegant dish. But when Tilopa sent him back yet a fifth time, Naropa was ashamed to show his face, and a great inner struggle raged within him. Finally, unable to face his guru's displeasure, he made up his mind to steal the entire pot.

Waiting for the right moment, he lingered on the fringes of the crowd, edging slowly toward the pot of curry. And as soon as all the guests and servants were preoccupied with some ceremonial occurrence, he abandoned his self-respect, snatched up the pot, hid it under his robes, and made his getaway.

Tilopa praised him for lowering himself to such a level of humiliation, further commending him for all his years of perseverance. Calling him "my diligent son," Tilopa then bestowed the initiation and blessing of Vajra Varahi upon him and gave him instruction in meditation.

Within six months Naropa gained mahamudra-siddhi, and a light began to flow from his being so intensely that it could be seen as far as a month's journey from his hermitage. His fame spread like wildfire, and devotees flocked to him from the four quarters of the world.

After years of tireless devotion to his countless disciples, he was assumed bodily into the Paradise of the Dakinis.

The Ka’bab Zhi (bKa’ babs bZhi) lineage of teachings were brought to Tibet by Marpa. They were initially received from Dharmakaya Buddha Dorje Chang (rDo rJe lCang) by the Mahasiddha Tilopa, who transmitted them to Naropa, Maitripa and Marpa. The lineage was then passed down through Milarépa to the Kagyüd (bKa’ brGyud) lineage of the Karmapas and other Lamas of both Kagyüd and Nyingma lineages.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche comments: "Tilopa is a profound example of the vajra master. He spared no effort in confronting his disciple Naropa with what was necessary. Naropa’s ability to receive transmission was obstructed by a welter of concepts as to what constituted spirituality and Tilopa manifested in the guise of whatever conflicted with Naropa’s conditioning. Because Naropa believed that Tilopa was the only one who could set him free from the constraints of his incomprehension, he was prepared to undergo repeated shocks to his ideological infrastructure. Tilopa was entirely politically incorrect from the point of view of Brahmanic society, and Naropa was locked into the Brahmanic paradigm. This was an explosive situation and one that led to Naropa’s realisation."

"People often think that Naropa’s trials at the hands of his teacher Tilopa are allegorical – but this may be a mistake, because the allegory is real. The vajra master in today’s world may not conjure in the same way that Tilopa conjured with Naropa, but he or she will still confront the disciple with his or her perceptual obstacles. The vajra master today will still cause offence to duality by whatever means are necessary. The disciple today will still complain that the vajra master is ‘unreasonable’ and expect the vajra master to conform to his or her own version of what spirituality should be. Naropa’s capacity may have been great – but his confusion is not different from our confusion. The stylistics of our confusion are different from those of Naropa and so the vajra master will approach our confusion as it is. The similarity is that the Mahasiddha vajra master will always offend our duality. The Mahasiddha vajra master will always insult our duality. The Mahasiddha vajra master will always infuriate our duality."

Naropa eventually passed away, resurrected into light, leaving no physical remains. His body of teachings, however, continues. Today it is the Gyalwa Karmapa who is the custodian of these precious methods whereby a person may attain Enlightenment in a single short lifetime.

Naropa, Mahasiddha: one of the principal Tantric Buddhist siddha of India. He is counted in both the Vajrasana and Abhayadatta Shri systems of enumerating the eighty-four mahasiddha. These great accomplished ones are regarded as being the original human source for most if not all of the Tantric literature and practice traditions of Tantric Buddhism. Naropa figures prominently in many lineages of tantric practice - especially honoured in the early Marpa Kagyu lineage of teachers.

The Tibetan Marpa Chokyi Lodro (1012-1099), founder of the Marpa Kagyu Tradition, having journeyed three times to India, studied extensively with Naropa. In the Sakya School Naropa is honoured as the originator of an important cycle of Vajrayogini practice counted as one of the very special teachings of Sakya. Lineages that include the name Naropa weave through all of the Sarma Schools of Tibetan Buddhism.