Th e idea to write Red Shambhala developed gradually

The idea to write Red Shambhala developed gradually as a natural off shoot of my other projects. Th e fi rst spark came ten years ago when I was doing research for my book Th e Beauty of the Primitive, a cultural history of shamanism. By chance, I found out that in a secret laboratory in the 1920s Gleb Bokii the chief Bolshevik cryptographer, master of codes, ciphers, electronic surveillance—and his friend Alexander Barchenko, an occult writer from St. Petersburg, explored Kabala, Sufi wisdom, Kalachakra, shamanism, and other esoteric traditions, simultaneously preparing an expedition to Tibet to search for the legendary Shambhala. A natural question arose: what could the Bolshevik commissar have to do with all this? Th e story of the life and death of

the Bolshevik secret police offi cer Bokii and his friend intrigued me. Meanwhile, I learned that during the same years, on the other side of the ocean in New York City, the Russian émigré painter Nicholas Roerich and his wife, Helena, were planning a venture into Inner Asia, hoping to use the Shambhala prophecy to build a spiritual kingdom in Asia that would provide humankind with a blueprint of an ideal social commonwealth. To promote his spiritual

scheme, he toyed with an idea to blend Tibetan Buddhism and Communism. Th en I stumbled upon the German-Armenian historian Emanuel Sarkisyanz’s Russland and der Messianismus des Orients, which mentioned that the same Shambhala legend was used by Bolshevik fellow travelers in Red Mongolia to anchor Communism

among nomads in the early 1920s.1 I came across this information when I was working on a paper dealing with the Oirot/Amursana prophecy that sprang up among Altaian nomads of southern Siberia at the turn of the twentieth century. Th is prophecy, also widespread in neighboring western Mongolia, dealt with the legendary hero some named Oirot and others called Amursana. The resurrected hero was expected to redeem suff ering people from alien intrusions and

lead them into a golden age of spiritual bliss and prosperity. Th is legend sounded strikingly similar to the Shambhala prophecy that stirred the minds of Tibetans and the nomads of eastern Mongolia. In my research I also found that the Bolsheviks used the Oirot/Amursana prophecy in the 1920s to anchor

themselves in Inner Asia. I began to have a feeling that all the individuals and events mentioned above might have somehow been linked. First of all, I need to outline at least briefl y what Shambhala means. It was a prophecy that emerged in the world of Tibetan Buddhism between the nine and eleven

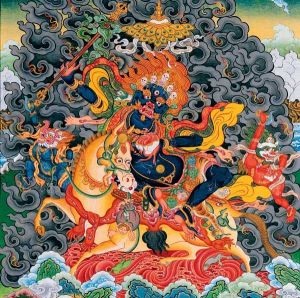

hundreds ce, centered on a legend about a pure and happy kingdom located somewhere in the north; the Tibetan word Shambhala means “source of happiness.”2 Th e legend said that in this mystical land people enjoyed spiritual bliss, security, and prosperity. Having mastered special techniques, they turned themselves into godlike beings and exercised full control over forces of nature. Th ey were blessed with long lives, never argued, and lived in harmony as

brothers and sisters. At one point, as the story went, alien intruders would corrupt and undermine the faith of Buddha. Th at was when Rudra Chakrin (Rudra with a Wheel), the last king of Shambhala, would step in and in a great battle would crush the forces of evil. Aft er this, the true faith, Tibetan Buddhism, would prevail and spread all over the world. Scholars argue that the paradisal image of Shambhala and the motif of the fi nal battle between good and evil, elements missing in original Buddhism, most likely were borrowed from neighboring religious traditions, particularly from Manichaeism and Islam, which was making violent advances on Buddhism in the early Middle Ages. In the course of time, indigenous lamas and later Western spiritual seekers muted

the “crusade” notions of the prophecy, and Shambhala became the peaceable kingdom that could be reached through spiritual enlightenment and perfection. Th e famous founder of Th eosophy Helena Blavatsky was the fi rst to introduce this cleansed version of the legend into Western esoteric lore in the 1880s. At the same time, she draped Shambhala in the mantle of evolutionary theory and progress, ideas widely popular among her contemporaries. Blavatsky’s Shambhala

was the abode of the Great White Brotherhood hidden in the Himalayas. Th e mahatmas from this brotherhood worked to engineer the socalled sixth race of spiritually enlightened and perfect human beings, who possessed superior knowledge and would eventually take over the world. Aft er 1945, when this kind of

talk naturally went out of fashion, the legend was refurbished to fi t new spiritual needs. Today in Tibetan Buddhism and spiritual literature, in both the

East and the West, Shambhala is presented as an ideal spiritual state seekers should aspire to reach by practicing compassion, meditation, and high spirituality. In this most recent interpretation of the legend, the old “holy war” feature is not simply set aside but recast into an inner war against

internal demons that block a seeker’s movement toward perfection.3 Recently it has become fashionable, especially among scholars, to debunk Western spiritual seekers who feed on Oriental wisdom. Anthropologists, cultural-studies scholars, and historians of religion deconstruct this spiritual trend that

has been very visible since the 1960s as a naïve “New Age myth” and point out how incorrect it is and how this spiritual romanticism has nothing to do with the “authentic” and “traditional” Tibetan Buddhism of Inner Asia.4 I want to stress at the outset that my book is not another academic exposure of the

Shambhala myth as a Western invention. The reason I am not going to do this is very simple: I am convinced that in matters of religion and spirituality it is pointless to argue what is authentic and genuine and what is not. Incidentally, I adopted the same approach in my previous book The Beauty of the

Primitive. So my premise is that in the field of spirituality everything is authentic, genuine, and traditional, including Eastern and Western versions of

Tibetan Buddhism along with its Shambhala myth in old and new forms. At the same time, Red Shambhala is not a spiritual treatise that calls you to partake of this myth by virtually traveling to the Shambhala land to reach some sort of spiritual enlightenment. Other authors, spiritual seekers, have

already done this, the best example being Edwin Bernbaum’s The Way to Shambhala. Th e purpose of my book is diff erent. I want to explore how the

Shambhala myth and related prophecies were used in Inner Asia and beyond between the 1890s and 1930s. I draw attention to the fact that the original Shambhala myth with its two sides (the spiritual paradise and the crusade against infi dels) and its later versions served diff erent purposes, depending

on circumstances and the people dealing with the legend. Some individuals profi led in this book became more attracted to the image of Shambhala as a country of spiritual bliss and the container of superior knowledge. Others turned to Shambhala as a vehicle to bring about a grand Buddhist theocracy in

Inner Asia. At the same time, several people were drawn to the old avenging side of the legend and used it as a tool of spiritual resistance. So the story I am going to tell deals with both the peaceful and avenging sides of the Shambhala myth. As the account unfolds, I will show why Shambhala suddenly became

relevant for a number of groups and individuals inside and outside Asia between the1890s and the 1930s. Prophecies usually stay dormant in times of peace and prosperity. Under normal circumstances, few people believe in utopias, share doomsday dreams of the total renewal of the world, or follow political

messiahs. Yet in a time of severe crisis or natural calamity, when the established routine of life falls apart and people feel insecure, prophecies, along with messiahs, multiply and come to the forefront. Th at is when people invoke old myths and legends and cling to various utopias promising ultimate

salvation. Th e period between the 1890s and 1930s was rich in social and political calamities, not only in Asia but all over the world. World War I and the collapse of four large empires (Chinese, Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian) followed by bloody revolutions created a fertile environment for

various religious and secular prophecies. Red Shambhala is the fi rst book in English that recounts the story of political and spiritual seekers, from the West and the East who used Tibetan Buddhist prophecies to promote their spiritual, social, and geopolitical agendas and schemes. Th ese were people of diff

erent persuasions and backgrounds: lamas (Ja-Lama and Agvan Dorzhiev), a painter-Th eosophist (Nicholas Roerich), a Bolshevik secret police cryptographer (Gleb Bokii), an occult writer with left ist leanings (Alexander Barchenko), Bolshevik diplomats and revolutionaries (Georgy Chicherin, Boris Shumatsky) along with their indigenous fellow-t ravelers (Elbek-Dorji Rinchino, Sergei Borisov, and Choibalsan), and the rightwing fanatic “Bloody White Baron” Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. Despite their diff erent backgrounds and loyalties, they shared the same totalitarian temptation—the faith in ultimate solutions. Th ey were on the quest for what one of them (Bokii) defi ned as the search for the source of absolute good and absolute evil. All of them were true

believers, idealists who dreamed about engineering a perfect free-of-socialvice society based on collective living and controlled by enlightened spiritual or ideological masters (an emperor, the Bolshevik Party, the Great White Brotherhood, a reincarnated deity) who would guide people on the “correct” path.

Healthy skepticism and moderation, rare commodities at that time anyway, never visited the minds of the individuals I profi le in this book. In this sense, they were true children of their time—an age of extremes that gave birth to totalitarian society. Much has been written about the appropriation of Tibet

and Shambhala by conservative and right-wing “cultural workers.” For example, we already know a great deal about Nazi ventures to the Himalayan Forbidden Kingdom that Himmler and his associates envisioned as the motherland of the Aryans.5 In Politics and the Occult, Gary Lachman has pointed out that popular

imagination tends to link the occult to the Right, which is not exactly correct.6 Red Shambhala proves yet again that people on the Left were no strangers to the occult, and they were equally mesmerized by the light from the East. In fact, it is more so in our day. Geographically I focus on Inner Asia, which roughly includes areas populated by people who either belonged to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition (Tibetans, Mongols, Tuvans, Buryat, and Kalmyk) or stood on its fringes (such as Altaians, sometimes called the Oirot people). For the

sake of convenience, I call this area the Mongol-Tibetan cultural area. At the same time, I will be making numerous detours to Russia, the United States,

Germany, and India. First, I will introduce the Mongol-Tibetan cultural area along with its deities and situate Shambhala and related prophecies in the historical context of Inner Asia. I propose that Shambhala, rather than being something unique, was part of the prophetic culture of the Mongol Tibetan world. What made the Shambhala legend stand out were the eff orts of the Panchen Lamas, spiritual leaders of Tibet who propagated it beginning in the 1700s, and later attempts of Western seekers to single out this legend and disseminate it in the West. My research into Oirot / Amursana prophecy and insights into the Geser legend popular among the Mongols and Buryat convinced me that we deal here with the same prophetic culture. Th e legends about

Oirot, Amursana, Geser, and Shambhala, which the nomads of Inner Asia frequently confl ated, essentially boil down to a story about a heroic redeemer who would appear when the world neared its end, save the righteous from the evil ones, and bring to life a dreamland of spiritual and material prosperity. Next my attention shift s to Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and Moscow of the 1920s as the Shambhala myth looms in the background. Here, I introduce English-speaking readers for the fi rst time to a fascinating story about the unusual partnership between the esoteric scientist and writer Alexander Barchenko and

his patron Gleb Bokii, the chief Bolshevik cryptographer who wanted to supplement a secular utopia (Communism) with a spiritual one (Shambhala). Driven by their desire to construct a new, nobler type of human being—a popular ideological fad among the early Bolsheviks—both wanted to tap into the Shambhala myth

and Kalachakra tantra, an esoteric Tibetan Buddhist teaching. Th e goal was to reinforce the Communist cause by using Asian wisdom. From Red Russia I shift back to Inner Asia and show how in the fi rst three decades of the twentieth century Shambhala, Geser, Oirot, and Amursana prophecies fed the rising nationalism of the Tibetans,

Mongols, Buryat, and Altaians. I explore the world of Bolshevik revolutionaries and their fellow travelers (Shumatsky, Borisov, and Rinchino) who tried to use popular Buddhism, including the mentioned prophecies, to anchor Bolshevism within Inner Asia. Th e fact that the Bolsheviks learned well how to massage

nationalist sentiments explains why Red Russia was able to sway some indigenous people in this area to its side, at least in the beginning of the 1920s. Here I also discuss Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, a notorious baron with occultist leanings, who briefl y highjacked Mongolia in 1921. I propose that both his rise and then quick demise could be attributed to his attitude to Mongol nationalism. Th en from Inner Asia I move to New York City and explore the world of two Russian émigré Theosophists, the painter Nicholas Roerich and his wife, Helena, companions in the quest for Shambhala. In the mid 1920s,

Nicholas, along with Helena and their son George, ventured to Tibet, posing as a reincarnation of the fi ft h Dalai Lama. With equal zeal he courted Red Russian diplomats and spies, American presidents, and Japanese politicians, promoting himself as a cultural celebrity destined to deliver an important

spiritual message to humankind. While many present-day Russian seekers treat the Roeriches as patriots and powerful spiritual teachers, American literature portrays them as dangerous gurus who at one point seduced FDR’s Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, costing him the presidential nomination in 1948. My

research for Red Shambhala at fi rst took me to the St. Petersburg Museum of Anthropology (Kunstkamera), where in 2007 I explored archival materials on Oirot and Amursana prophecies. Two years later, in order to better understand how the Bolsheviks used Tibetan Buddhism to promote their agenda in Inner

Asia in the 1920s, I visited the Russian Archive of Social and Political History in Moscow. Th ere I mined the papers of Comintern, a Moscow-based organization that had been preoccupied with sponsoring Communism all over the world. Another source, the recently published spiritual journals of Helena Roerich, gave me deeper insight into the minds of the Roeriches.7

However, I do not want to create the impression that I am the fi rst trailblazer to touch upon these topics. I have several important predecessors, mostly

from Russia, and I drew heavily upon their valuable works. I owe much to the historian Alexandre Andreev, who was the first to track Bolshevik advances into Tibet.8 I am equally indebted to another historian, Vladimir Rosov, whose two volumes on Roerich are the most complete biography of this painter and

spiritual seeker.9 I also used Barchenko’s correspondence and the records of his interrogation from formerly classified documents first brought to light by Moscow investigative reporter Oleg Shishkin.10 During the early stages of this project, I also greatly benefi ted from John McCannon’s and Markus

Osterrieder’s essays, which provide the best overviews of Nicholas Roerich’s activities available in English.11 For thought-provoking ideas that helped me situate Tibetan Buddhist prophecies and Bolshevik relations with Asian nomads, I am indebted to Sarkisyanz and to Terry Martin.12 Sarkisyanz has not only

discussed Soviet Marxism as a form of a surrogate secular religion, but also was the fi rst to show how the Bolshevik prophetic message was customized to the aspirations of traditional and tribal societies in Russia and Asia. Although lengthy and not exactly easy to read, Martin’s book provides a brilliant analysis of the Bolsheviks’ policies in the 1920s that allowed them to woo to their side various non-Russian nationalities, including nomadic societies of

Asia. Th e last but not least words of gratitude go to the people who made this book possible. First of all, I want to mention Richard Smoley from Quest Books, who liked the idea of Red Shambhala from the very beginning and encouraged me to put it into a book form. Sharron Dorr and Will Marsh, two other editors from the same press, made sure that this project was put into a good shape. Moreover, Will went as far as immersing himself into my topic and

giving me valuable tips that saved me from several embarrassing inconsistencies. I also want to thank the Department of History at the University of Memphis, and especially its chair, Dr. Jannan Sherman, who created wonderful writing opportunities for me, made sure that I had funding for my research, and helped

make my first two years in Memphis as smooth as possible. At the final stage of the project, Daniel Entin, director of the Roerich Museum in New York City, generously provided all necessary photographs and copies of rare articles that I urgently needed to complete this book. To be honest, I have never

experienced such prompt help in any other libraries and archives. And, finally, I am grateful to A. E. G. Patterson, who suddenly, as if by magic, emerged on the horizon and offered me rigorous editorial assistance in improving the text.