The Philosophy behind Buddhism - Mary Hendriks

A contemporary view of Buddhism with reference to the contemporary Buddhist author Stephen Batchelor from his book “Buddhism without Beliefs”.

The theme of today's talk is the central philosophy of Buddhism, and I will discuss this from two perspectives, one from the conventional understanding of many Buddhist groups and the other from Stephen Batchelor's contemporary work, as outlined in his book "Buddhism Without Beliefs".

First I will be talking about commonly accepted Buddhist teaching. In the second part of the talk, I will cover Stephen Batchelor's ideas.

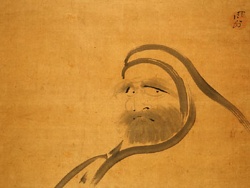

Just to set the scene - the man called Siddhartha Gautama, who became known as The Buddha, lived around 2,500 years ago in northern India near the border of Nepal. He grew up a wealthy prince, married and had a son, but left this short life of affluence for a spiritual journey to find answers to the questions of suffering, ageing and death.

He felt that these were the main questions about living. We all face suffering -I think it would be safe to say that everyone here, at some time, has suffered. Despite cosmetic surgery and face creams, we all age. I'd like you to put your hand up if you are intending to live forever! So we all are touched by death. And that was Siddhartha's quest, to find meaning in living. Out of that journey, Siddhartha Gautama developed a teaching known as the "Dharma".

After several years of learning from the teachers of his day, and living a very austere and meditative life, Siddhartha reached an understanding, called "enlightenment", and became known from this point as "the Buddha", meaning the "awakened one". For the next 50 years, he travelled around India talking to people, discussing and sharing what he had learned.

What he taught was a guideline, not a set of rules, for successful living, and the Buddha never claimed divinity, nor did he teach about a higher or divine presence. This teaching spread across Asia and, over time, became different schools, just as we have many styles of Christian practice. After two hundred years, the world of dharma teaching split into two - the more traditional Theravada and the newer Mahayana school, from which today we have several Zen and Pure Land styles of teaching. A much later evolution produced a third stream called Vajrayana and this resulted in four Tibetan schools. Most people associate His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama, with Buddhism as a whole group, but he is the spiritual leader of just one of the Tibetan Buddhist schools and does not represent all Buddhists, just like the Pope who represents Catholics but not all Christians.

The Buddha taught a process of thinking - he actually used a parable of a raft to tell us to use that thinking - like a raft - to take us to another level, and then - if it no longer meets our needs, (Shock horror) - to let it go! -to move on to another level.

This is not the stuff of religion where a security of fixed belief is paramount. However, as happens, over time, Buddhism, in most of its various forms, developed into religious communities with belief systems. In this modern time, across the world, Buddhist leaders are invited to join in interfaith meetings, as "clergy".

But is Buddhism a religion? It does not teach about a personal God. And the founder said that what he showed was a path, he was like the man pointing at the moon. And that we should not look at the pointing finger, (not at him) but we should all look for the moon.

What are the main teachings of Buddhism? The primary teaching of the Buddha, the dharma, centres around what is known as The Four Noble Truths, The Eightfold Path and Dependent Origination. Buddhism also has this cool practice of meditation, a listening within, which I will not discuss today, as this really is a full topic on its own.

The Four Noble Truths, which the Buddha understood at the enlightenment, is a logical process of seeing life, seeing all actions, not as we wish to see them, but as they really are.

The first truth is that life always incorporates suffering or Dukkha as it was called then. Dukkha has a broader meaning than suffering. It can be the feeling you experience when you encounter pain, old age, sickness, loss, or separation from loved ones, but it can also represent a general unsatisfied feeling. If you feel that your life is like pushing a supermarket trolley, which always wants to go in a different direction, then that's dukkha.

The second noble truth is that suffering in its broad sense, comes from desire, and specifically, desire for meeting our expectations and for self fulfillment as we see it. By desiring for ourselves rather than the whole, we will always have suffering.

In our society, we are raised on the principle of desire, it's what makes our society the way it is, and we are encouraged to desire, to want more, to acquire and then to then move on to another desire. All the time, our lives are only temporarily satisfied.

These two truths are the bad news! But Buddhism is a positive philosophy, and the next two noble truths give an optimistic message.

The third noble truth tells us that if our attachment to desire ends, so too will the suffering. Specifically, if we change our perception and reduce our attachment to desire, suffering will also reduce. This is not intended to lead to a cancellation of the zest for life, but to an understanding of the nature of life and to controlling those desires, which come from that lack of understanding. And I see this as a significant truth for our society, that once we come to a deeper understanding then we begin to see the nature and origin of our desires and our expectations -expectations about marriage partners, about children, about our desire for new goods, a bigger house, a faster car, about our desire for travel, for entertainment, and always seeking something new. Once we realize that we are attached to that continuous cycle of desire, we can then begin to let go of that attachment. This process of letting go is the key to freedom from suffering.

The fourth noble truth is a practical set of understanding and ethics to help us to reduce suffering. The Buddha called this the middle way, and it's a set of eight guidelines called the Eightfold path. The Eightfold Path outlines guidelines for day-to-day living, a system of right understanding and right action. There is some analogy here with the Ten Commandments in Christianity, but the Eightfold Path was meant as a guideline and a course of action, rather than a set of strict rules.

The Buddha reached this middle way after himself living the extremes of life. In his early years, he was surrounded by luxury, as a local Prince, given access to all pleasures available at that time. In his search, he lived the opposite life, one where he deprived himself of even the essentials, and faced death. The Noble Eightfold path leads to a way, which embraces life and is neither indulgent nor austere.

The other main teaching of Buddhism is the concept of Dependent Origination, which sounds complex, but is really quite simple. It's one of the most important concepts of the Buddhist teaching and I think, the one which defines Buddhism as an agnostic philosophy.

The Buddha said, that to become enlightened, you need only to understand The Four Noble Truths and Dependent Origination.

Dependent Origination is also called the law of causality. It teaches that nothing exists on its own, but has always come from earlier circumstances. Therefore, there is no divine intervention.

A piece of paper does not come into existence spontaneously. It is made from wood pulp and water. The wood comes from trees, which comes from seeds from earlier trees. If you burn paper, it becomes smoke and ash, so it has not disappeared but transformed. The essential components of that piece of paper were always there, and will always be there. A pot is made because once a potter took clay and formed it on a wheel and then fired the pot. Many circumstances and components were needed for the process.

In the same way, we did not spontaneously come into existence at birth. We are the result of our parents, of the circumstances of their meeting, and of all that happened before. You are alive today because you were once born, as a result of your parents meeting at an earlier time. Every thing is always a consequence of something before, that is, the origin of everything is not unique, and everything depends on a particular set of circumstances having happened. This is a changing reality, and the Buddha did not see us as having anything fixed. That includes no fixed soul. We have a spiritual nature, but that is dynamic and flowing, not something that we acquire at birth, nor something we are stuck with, but a spiritual nature that is changing, from moment to moment. We are the result of our genetics, our environment, our parents, our societies, and of our own choices and actions. And this is not fixed.

If you begin to see everything as dependent on everything else, then you will need to look to the larger picture, where everything we think and do affects the future. As in the writing of the Vietnamese monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, "the world is woven of interconnected threads". So we are living in a world that is the result of previous generations, and our actions add to the shape the world of the future. We are individually and collectively responsible.

In essence, the Buddha did not see a separate and benevolent creator who could act on our behalf. He saw the interdependence of all life and the cause and effect of actions, which create their own future.

Buddhism therefore is not about humans having dominion over nature - we are just one part of the process of life. The Buddha was revolutionary in his teaching. He taught that women were equal and could teach, that slavery was wrong and he also questioned ownership of animals. How could one part of life own another?

This is why Buddhism, at its inception, was more of a way of life than a religion. However, now it is practiced more as a religion by many followers who worship in the temples and seek divine guidance from the Buddha nature.

In many Buddhist schools, the four noble truths are taught as a belief system, something fixed, rather than as something to be understood, and this brings me to the second part of this talk - about the views of Stephen Batchelor.

Stephen Batchelor was formally trained in Buddhist traditions. He was born in Scotland in 1953, grew up in England, and left for India at age 18, to train as a monk in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. He later trained in the Zen Buddhist tradition in South Korea. In 1985, he disrobed, married ex Buddhist nun, Martine, and returned to England where he co-founded Sharpham College for Buddhist Studies and Contemporary Inquiry.

In his book "Buddhism without Beliefs", Stephen says that the Buddha was not a mystic, and that he did not claim to have "privileged, esoteric information of how the universe ticks". According to Stephen, the Buddha experienced the four truths as "ennobling", as a new freedom, and Stephen refers to the four ennobling truths, which are like a prescription, a recipe to empower.

Stephen Batchelor writes about quite a different and evolving contemporary dharma practice, one based on the original teaching and new thinking, a philosophy of action, rather than a dogmatic belief system.

Stephen's view, from his extensive research into Buddhist literature, his experiences, and his own thinking, is that Buddhism has become an "ism", a belief system, a religious, dogmatic and ritualized practice. His view is that Siddhartha Gautama suggested a course of action, a challenge to act. The first and second ennobling truths challenge our relationship to our existence, to our habit of fear and worry. By understanding desire, by developing a new view of ourselves and the world, we are able to let go, to move, perhaps just for a moment, to a new dimension of the flow of life. Stephen sees this "like a momentary gap in the clouds".

Over time, many of the Buddhist groups taught that the state of "awakening" was some higher and less achievable state, one that required their own defined, and lengthy processes to reach this knowledge. Some groups even decided that women were unlikely to ever achieve this knowledge in one life. Stephen rejects this, but leaves us with some ambiguous logic by saying "awakening is indeed close by - and supreme effort is required to realize it. Awakening is indeed far away - and readily accessible".

Stephen writes that the dharma, as taught by the Buddha, is not something to believe in, but something to do. Therefore, Buddhism is an agnostic philosophy, a method to be investigated and trialed. He agues that this is an agnosticism based on a recognition that "I do not know", and that this agnosticism could be for some, a system of ethics, for others a philosophy or a contemplative psychotherapy. He sees a trend, however, of Buddhism being identified with religion and with the many styles of meditation, and thereby no longer able to offer practice for an agnostic and pluralistic world.

One main chapter in the book "Buddhism without Beliefs" covers the topic of rebirth. Stephen Batchelor begins this chapter with a comment: "religions are united not by belief in God but by belief in life after death".

All religions have some explanation for what happens after death, and the ancient Indian religions of the era when the Buddha lived provided an explanation of reincarnation, with a rebirth based on the ethical actions of the previous life. And the Buddha is quoted as describing his previous lives and of teaching about the cycle of rebirth. Stephen argues that this simply reflected the worldview at that time. He says that most people at that time also believed the world to be flat, rather than the quite pretty round shape we can see from space. Religious Buddhism emphasized that the denial of rebirth would undermine social and ethical responsibility and so it stayed.

Stephen comments that belief in a future rebirth allows orthodox Buddhist schools to teach postponing personal and social fulfillment until a future rebirth. These schools rarely become involved in the anguish of the contemporary world, and focus on an individual's personal awakening and future rebirth. And except for a few schools, they rarely become involved in social issues.

And on this point I am in agreement with Stephen Batchelor. My personal view is that Buddhism is a great philosophy for personal development and for understanding our connection with nature and with life, but it lacks a culture of social engagement. Buddhist philosophy deals with understanding our place in the living world, but many 21st Century Buddhist leaders offer little guidance for a world that desperately needs a new world-view, a world where we rethink and redefine our concepts of what makes a successful global community.

There is still possibility for change. Buddhism has a long history, and each time it moved into a new civilization or historical period, it had the challenge of maintaining coherent tradition and being relevant to the needs of the people in the new situation. So the colourful history of the many groups today has led to Buddhism in many flavours, most with hierarchies, rules and traditions. And Stephen writes that this is the strength of religious Buddhism in that these hierarchic institutions have weathered centuries of turmoil and change. However, at the same time, he writes that it is now time for new look with contemporary eyes.

I would like to quote Stephen's last paragraph of his book "Buddhism without Beliefs". Stephen writes: " An agnostic Buddhist vision of a culture of awakening will inevitably challenge many of the time-honoured roles of religious Buddhism. No longer will it see the role of Buddhism as providing pseudoscientific authority on subjects such as cosmology, biology, and consciousness as it did in pre-scientific Asian cultures. Nor will it see its role as offering consoling assurances of a better afterlife by living in accord with the worldview of karma and rebirth. Rather than the pessimistic Indian doctrine of temporal degeneration, it will emphasize the freedom and responsibility to create a more awakened and compassionate society on this earth. Instead of authoritarian, monolithic institutions, it could imagine a decentralized tapestry of small-scale, autonomous communities of awakening. Instead of a mystical religious movement ruled by autocratic leaders, it would forsee a deep agnostic, secular culture founded on friendships and governed by collaboration."

And -, as you can guess from this quote, Stephen Batchelor is not popular with many orthodox Buddhist groups!

The world of the 21st century is one where we are questioning the way our societies have evolved, and the values of the consumer society and growth economy. It is also one where personal awareness and freedom are highly valued, and so one where many find the teaching of the Buddha very appealing.

In his work, Stephen has taken a contemporary look at the dharma, the teaching of the Buddha, and rejected the elitism, the dogma, the rituals and some ancient beliefs of religious Buddhism. At the same time, he has reminded us of the core nature of Buddhist philosophy and about a path of action, a way of being in our communities and responding to the challenges of our existence.

Stephen Batchelor is an agnostic philosopher with a great passion for the work of another exceptional philosopher, a man who lived 2,500 years ago, a man who was called the Buddha.