Difference between revisions of "The historical Buddha"

(Created page with "<poem> THE historical Buddha, as known to the custodians of the Esoteric Doctrine, is a personage whose birth is not invested with the quaint marvels popular story has crowde...") |

|||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{DisplayImages|1933|187|504|661|1545|650|1971|1314|400|277|637|1096|916|423|1694|1463|1470|347|92}} | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| + | In January 1898 an Englishman, W. C. Peppe, digging into a mound on his estate at Pipdihwa just the [[Indian]] side of the IndianNepalese border, unearthed a soapstone [[vase]] some six inches in height with a brief inscription around its lid. The inscription, written in the [[Brahmi]] [[script]] and dating from about the second century BCE, was in one of the {{Wiki|ancient Indian}} {{Wiki|dialects}} or [[Prakrits]] collectively referred to as Middle [[Wikipedia:Indo-Aryan peoples|Indo-Aryan]]. The precise [[interpretation]] of the inscription remains problematic, but it appears to claim that the [[vase]] is 'a receptacle of [[relics]] of the Blessed [[Buddha]] of the Sakyas'.1 The circumstances of this find and the find itself actually reveal a considerable amount about the [[nature]] and long history of what we know today as '[[Buddhism]]'. | ||

| − | + | Peppe was among the early excavators of ruined [[Buddhist]] stiipas or monumental burial mounds. Such [[stupas]] vary considerably in size. The largest were made to enshrine the [[relics]] of the [[Buddha]] himself or of [[Buddhist]] '[[saints]]' or [[arhats]] ([[Pali]] [[arahat]]), while smaller ones contained the remains of more ordinary men and women.2 Today countless [[stupas]] are to be found scattered across the [[Indian]] subcontinent (where over the {{Wiki|past}} hundred years a few have been restored to something of their former glory) and also other countries where [[Buddhism]] spread. [[Buddhism]] was, then, in origin an [[Indian]] [[phenomenon]]. Beginning in the fifth century BCE, its teachings and {{Wiki|institutions}} continued to flourish for some fifteen centuries on [[Indian]] soil, inspiring and moulding the [[intellectual]], [[religious]], and {{Wiki|cultural}} [[life]] of [[India]]. | |

| − | + | During this period [[Buddhism]] spread via the old trade routes far beyond the confines of [[India]] right across {{Wiki|Asia}}, from {{Wiki|Afghanistan}} in the [[west]] to [[Japan]] in the [[east]], affecting and [[touching]] the [[lives]] of millions of [[people]]. Yet by around the close of the twelfth century Bud" dhist {{Wiki|institutions}} had all but disappeared from [[India]] proper, and it is in the countries and cultures that lie beyond [[India]] that [[Buddhism]] flourishes today. None the less all the variou~ living [[traditions]] of [[Buddhism]] in some way look back to and revere a figure who has a certain basis in history-a figure who lived and [[died]] in {{Wiki|northern India}} several centuries before the beginning of the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}} and belonged to a [[people]] known as the [[Sakyas]] ([[Pali]] [[Sakya]]). He is [[Sakya-muni]], 'the [[Wikipedia:Sage (sophos|sage]] of the [[Sakyas]]', or as our inscription prefers to call him [[buddho]] bhagavii-'the Blessed [[Buddha]]', 'the [[Lord Buddha]]'. So who, and indeed what, was the [[Lord Buddha]]? | |

| − | + | This is a quesc tion that might be answered in a number of different ways, a question about which both the [[Buddhist tradition]] and the historian have something to say. The [[nature]] of the [[Buddha]] is a [[subject]] that the [[Buddhist tradition]] itself has expounded on at length and to which we will return below but, in brief, the [[word]] b_uddha is not a [[name]] but a title; its meaning is 'one who has woken up'. This title is generally applied by the [[Buddhist tradition]] to a class of [[beings]] who are, from the {{Wiki|perspective}} of ordinary [[humanity]], extremely rare and quite [[extraordinary]]. In contrast to these [[Buddhas]] or '[[awakened ones]]' the {{Wiki|mass}} of [[humanity]]; along with the other creatures and [[beings]] that constitute the [[world]], are asleep-asleep in the [[sense]] that they pass through their [[lives]] never [[knowing]] and [[seeing]] the [[world]] 'as it is' (yathii-bhutarrt). As a consequence they [[suffer]]. | |

| − | + | A [[buddha]] on the other hand awakens to the [[knowledge]] of the [[world]] as it truly is and in so doing finds [[release]] from [[suffering]]. Moreover-and this is perhaps the greatest significance of a [[buddha]] for the rest of [[humanity]], and indeed for all the [[beings]] who make up the universe-a [[buddha]] teaches. He teaches out of [[sympathy]] and [[compassion]] for the [[suffering]] of [[beings]], for the [[benefit]] and {{Wiki|welfare}} of all [[beings]]; he teaches in order to lead others to [[awaken]] to the [[understanding]] that brings final relief from [[suffering]]. An {{Wiki|ancient}} [[formula]] still used in [[Buddhist]] devotions today puts it as follows: For the following [[reasons]] he is a [[Blessed One]]: he is an [[Arhat]], a perfectly and completely [[awakened one]], {{Wiki|perfect}} in his [[understanding]] and conduct, [[happy]], one who [[understands]] the [[world]], an [[unsurpassed]] trainer of unruly men, the [[teacher]] of both [[gods]] and men, a blessed buddha.3 Such is a [[buddha]] in general terms, but what of the particular [[buddha]] with whom we started, whose [[relics]] appear to have been enshrined in a number of [[stupas]] across the [[north]] of [[India]] and to whom the [[Buddhist tradition]] looks as its particular founderthe [[historical Buddha]]? | |

| − | + | Let us for the [[moment]] consider the question not so much from the {{Wiki|perspective}} of the [[Buddhist tradition]] as from the {{Wiki|perspective}} of the historian. The [[Buddha]] and the [[Indian]] 'renouacer' [[tradition]] We can know very little of the [[historical Buddha]] with any [[degree]] of {{Wiki|certainty}}. Yet within the bounds of reasonable historical {{Wiki|probability}} we can [[form]] quite a clear picture of the kind of [[person]] the [[Buddha]] was and the main events of his [[life]]. The oldest [[Buddhist]] sources, which provide us with a number of details concerning the [[person]] and [[life of the Buddha]], date from the fourth or third century BCE. Unfortunately when we tum to the nonBuddhist sources of a similar date, namely the earliest texts of the [[Jain]] and [[brahmanical]] [[traditions]], there is no explicit mention of the [[Buddha]] at all.4 It would be a mistake to conclude, however, that [[non-Buddhist]] sources thus provide us with no corroborative {{Wiki|evidence}} for the picture of the [[Buddha]] painted in early [[Buddhist texts]]. | |

| − | + | [[Essentially]] the [[latter]] {{Wiki|present}} the [[Buddha]] as a sramatJa ([[Pali]] samaf}a). This term means literally 'one who strives' and belongs to the technical vocabulary of [[Indian]] [[religion]], referring as it does to 'one who strives' religiously or [[spiritually]]. It points towards a particular [[tradition]] that in one way or another has been of great significance in [[Indian]] [[religious]] history, be it [[Buddhist]], [[Jain]], or [[Hindu]]. Any quest for the [[historical Buddha]] must begin with the sramatJa [[tradition]]. Collectively our sources may not allow us to write the early history of this {{Wiki|movement}} but they do enable us to say a certain amount concerning its [[character]]. The [[tradition]] is sometimes called the 'renouncer (sarrmyiisin) [[tradition]]'. What we are concerned with here is the [[phenomenon]] of {{Wiki|individuals}}' renouncing their normal role in {{Wiki|society}} as a member of an extended 'household' in order to devote themselves to some [[form]] of [[religious]] or [[spiritual]] [[life]]. The 'renouncer' abandons [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] means of [[livelihood]], such as {{Wiki|farming}} or trade, and adopts instead the [[religious]] [[life]] as a means of [[livelihood]]. That is, he | |

| − | + | becomes a [[religious]] {{Wiki|mendicant}} dependent on [[alms]]. What our sources make clear is that by the fifth century BCE this [[phenomenon]] was both widespread and varied. Thus while 'renouncers' had in common the fact .that they had 'gone forth from the [[household life]] into homelessness' (to use a [[phrase]] common in [[Buddhist]] sources), the kind of [[lifestyle]] they then adopted was not necessarily the same. This is suggested by some of the terms that we find in the texts: in addition to 'one who strives' and 'renouncer', we fil).d '{{Wiki|wanderer}}' (parivriijaka/paribbiijaka), 'one who begs his share [of [[alms]])' (bhik(fulbhikkhu), 'naked [[ascetic]]' (ace/aka), 'matted-hair [[ascetic]]' ([[jatila]]), as well as a number of other terms.5 | |

| + | Some of these [[wanderers]] and [[ascetics]] seem to have been loners, while others seem to have organized themselves into groups and lived under a [[teacher]]. Early renouncers seem to· have been for the most part {{Wiki|male}}, although with the growth of [[Buddhism]] and [[Jainism]] it is certainly the case that women too began to be numbered among. their ranks. | ||

| − | + | Three kinds of [[activity]] seem to have preoccupied these [[wanderers]] and. [[ascetics]]. First, there is the [[practice of austerities]], such as going naked in all weathers, enduring all [[physical]] discomforts, [[fasting]], or {{Wiki|undertaking}} the [[vow]] to live like a {{Wiki|cow}} or . even a dog.6 Secondly, there is the [[cultivation]] of [[meditative]] and {{Wiki|contemplative}} techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as 'altered states of [[consciousness]]'. | |

| − | + | In the technical vocabulary of [[Indian]] [[religious]] texts such states come to be termed '[[meditations]]' (dhyiina/jhiina) or 'concentrations' (samiidhi); the [[attainment]] of such states of [[consciousness]] was generally regarded as bringing the [[practitioner]] to some deeper [[knowledge]] and [[experience]] of the [[nature]] of the [[world]]. Lastly there is the [[development]] of various [[philosophical]] [[views]] providing the [[intellectual]] {{Wiki|justification}} for particular practices and the {{Wiki|theoretical}} expression of the '[[knowledge]]' to which they led. While some groups and {{Wiki|individuals}} seem to have combined all three [[activities]], others favoured one at the expense of the others, and the line between th'e [[practice of austerities]] and the practice of [[meditation]] may not always be clear: the practice of extreme austerity will certainly alter one's [[state of mind]]. | |

| − | + | The [[existence]] of some of these different groups of {{Wiki|ancient Indian}} [[wanderers]] and [[ascetics]] with their various practices and theories finds expression in [[Buddhist texts]] in a stock description of 'six [[teachers]] of other schools', who are each represented as expounding a particular [[teaching]] and practice. Another list, with no details of the associated teachings and practices, gives ten types of renouncer. In fact two other {{Wiki|ancient Indian}} [[traditions]] that were subsequently of some importance in the [[religious]] [[life]] of [[India]] (the [[Ajivikas]] and the [[Jains]]) find a place in both these {{Wiki|ancient}} [[Buddhist]] lists; the [[Jain]] [[tradition]], of course, survives to this day.7 But one of the most significant groups for the [[understanding]] of the [[religious]] {{Wiki|milieu}} of the [[historical Buddha]] is omitted from these lists; this is the early [[brahmanical]] [[tradition]]. To explain who the · [[brahmins]] ( briihma1Ja) were requires a brief excursus into the early [[evolution]] of [[Indian]] {{Wiki|culture}} and {{Wiki|society}}. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | THE [[historical Buddha]], as known to the custodians of the [[Esoteric]] [[Doctrine]], is a personage whose [[birth]] is not invested with the quaint marvels popular story has crowded round it. Nor was his progress to adeptship traced by the literal occurrence of the [[supernatural]] struggles depicted in [[symbolic]] legend. On the other hand, the [[incarnation]], which may outwardly be described as the [[birth]] of [[Buddha]], is certainly not regarded by [[occult]] [[science]] as an event like any other [[birth]], nor the [[spiritual]] [[development]] through which [[Buddha]] passed during his earth-life a mere process of [[intellectual]] [[evolution]], like the [[mental]] {{Wiki|history}} of any other [[philosopher]]. | |

| − | + | The mistake which ordinary {{Wiki|European}} writers make in dealing with a problem of this sort lies in their inclination to treat [[exoteric]] legend either as a record of a [[miracle]] about which no more need be said, or as [[pure]] [[myth]], putting merely a fantastic decoration on a remarkable [[life]]. This, it is assumed, however remarkable, must have been lived according to the theories of [[Nature]] at {{Wiki|present}} accepted by the nineteenth century. The account which has now been given in the foregoing pages may prepare the way for a statement as to what the [[Esoteric]] [[Doctrine]] teaches concerning the {{Wiki|real}} [[Buddha]], who was born, as {{Wiki|modern}} [[investigation]] has quite correctly ascertained, 648 years before the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}}, at Kapila-Vastu near [[Benares]]. | |

| − | + | [[Exoteric]] conceptions, [[knowing]] [[nothing]] of the laws which govern the operations of [[Nature]] in her higher departments, can only explain an abnormal [[dignity]] attaching to some particular [[birth]] by supposing that the [[physical body]] of the [[person]] concerned was generated in a miraculous [[manner]]. Hence the popular notion about [[Buddha]], that his [[incarnation]] in this [[world]] was due to an immaculate {{Wiki|conception}}. [[Occult]] [[science]] [[knows]] [[nothing]] of any process for the production of a [[physical]] [[human]] child other than that appointed by [[physical]] laws; but it does [[know]] a good deal concerning the limits within which the progressive “one [[life]],” or “[[spiritual]] monad,” or continuous thread of a series of [[incarnations]], may select definite child-bodies as their [[human]] tenements. By the operation of [[Karma]], in the case of ordinary mankind, this election is made, {{Wiki|unconsciously}} as far as the antecedent, [[spiritual]] [[Ego]] [[emerging]] from [[Devachan]] is concerned. | |

| − | + | But in those abnormal cases where the one [[life]] has already forced [[it-self]] into the sixth [[principle]] — that is to say, where a man has become an {{Wiki|adept}}, and has the [[power]] of guiding his [[own]] [[spiritual]] [[Ego]], in full [[consciousness]] as to what he is about, after he has quitted the [[body]] in which he won adept-ship, either temporarily or permanently — it is quite within his [[power]] to select his [[own]] next [[incarnation]]. During [[life]], even, he gets above the [[Devachanic]] [[attraction]]. He becomes one of the [[conscious]] directing [[powers]] of the {{Wiki|planetary}} system to which he belongs; and great as this {{Wiki|mystery}} of selected [[re-incarnation]] may be, it is not by any means restricted in its application to such [[extraordinary]] events as the [[birth]] of a [[Buddha]]. | |

| − | + | It is a [[phenomenon]] frequently reproduced by the higher {{Wiki|adepts}} to this day, and while a great deal recounted in popular {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[mythology]] is either purely fictitious or entirely symbolical, the [[re-incarnation]] of the [[Dalai]] and Teshu [[Lamas]] in [[Tibet]], at which travelers only [[laugh]] for want of the [[knowledge]] that might enable them to sift fact from fancy, is a sober [[scientific]] [[achievement]]. In such cases the {{Wiki|adept}} states beforehand in what child, when and where to be born, he is going to [[re-incarnate]], and he very rarely fails. | |

| − | + | We say very rarely, because there are some accidents of [[physical]] [[nature]] which cannot be entirely guarded against; and it is not absolutely certain that, with all the foresight even an {{Wiki|adept}} may bring to bear upon the {{Wiki|matter}}, the child he may choose to become, in his re-incarnated [[state]], may attain [[physical]] maturity successfully. And, meanwhile, in the [[body]], the {{Wiki|adept}} is relatively helpless. Out of the [[body]] he is just what he has been ever since he became an {{Wiki|adept}}; but as regards the new [[body]] he has chosen to inhabit, he must let it grow up in the ordinary course of [[Nature]], and educate it by ordinary {{Wiki|processes}}, and [[initiate]] it by the regular [[occult]] method into adeptship, before he has got a [[body]] fully ready again for [[occult]] work on the [[physical]] plane. | |

| − | + | All these {{Wiki|processes}} are immensely simplified, it is true, by the peculiar [[spiritual]] force working within; but at first, in the child’s [[body]], the {{Wiki|adept}} [[soul]] is certainly cramped and embarrassed, and, as ordinary [[imagination]] might suggest, very uncomfortable and ill at ease. The situation would be very much misunderstood if the reader were to [[imagine]] that [[re-incarnation]] of the kind described is a privilege which {{Wiki|adepts}} avail themselves of with [[pleasure]]. | |

| − | + | [[Buddha’s]] [[birth]] was a {{Wiki|mystery}} of the kind described, and by the [[light]] of what has been said it will be easy to go over the popular story of his miraculous origin, and trace the [[symbolic]] references to the facts of the situation in some even of the most grotesque fables. None, for example, can look less [[promising]] as an allusion to anything like a [[scientific]] fact than the statement that [[Buddha]] entered the side of his mother as a young white [[elephant]]. | |

| − | + | But the white [[elephant]] is simply the [[symbol]] of adept-ship, — something considered to be a rare and [[beautiful]] specimen of its kind. So with other ante-natal {{Wiki|legends}} pointing to the fact that the {{Wiki|future}} child’s [[body]] had been chosen as the habitation of a great [[spirit]] already endowed with superlative [[wisdom]] and [[goodness]]. [[Indra]] and [[Brahma]] came to do homage to the child at his [[birth]]; that is to say, the [[powers]] of [[Nature]] were already in submission to the [[Spirit]] within him. The [[thirty-two signs]] of a [[Buddha]], which {{Wiki|legends}} describe by means of a ludicrous [[physical]] [[symbolism]], are merely the various [[powers]] of adept-ship. | |

| − | + | The [[selection]] of the [[body]] known as [[Siddhartha]], and afterwards as [[Gautama]], son of [[Suddhodana]], of Kapila-Vastu, as the [[human]] tenement of the [[enlightened]] [[human]] [[spirit]], who had submitted to [[incarnation]] for the [[sake]] of [[teaching]] mankind, was not one of those rare failures spoken of above; on the contrary, it was a signally successful choice in all respects, and [[nothing]] interfered with the [[accomplishment]] of adeptship by the [[Buddha]] in his new [[body]]. The popular {{Wiki|narrative}} of his [[ascetic]] struggles and temptations, and of his final [[attainment]] of [[Buddhahood]] under the [[Bo-tree]], is [[nothing]] more, of course, than the [[exoteric]] version of his [[initiation]]. | |

| − | + | From that period onward, his work was of a dual [[nature]]; he had to reform and revive the {{Wiki|morals}} of the populace and the [[science]] of the {{Wiki|adepts}}, — for adeptship itself is [[subject]] to cyclic changes, and in need of periodical {{Wiki|impulses}}. The explanation of this branch of the [[subject]], in plain terms, will not alone be important for its [[own]] [[sake]], but will be [[interesting]] to all students of [[exoteric Buddhism]], as elucidating some of the puzzling complications of the more abstruse “[[Northern]] [[doctrine]].” | |

| − | + | A [[Buddha]] visits the [[earth]] for each of the seven races of the great {{Wiki|planetary}} period. The [[Buddha]] with whom we are occupied was the fourth of the series, and that is why he stands fourth in the list quoted by Mr. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}}, from Burnouf,—quoted as an illustration of the way the [[Northern]] [[doctrine]] has been, as Mr. Davids supposes, inflated by [[metaphysical]] subtleties and absurdities crowded round the simple [[morality]] which sums up [[Buddhism]] as presented to the populace. The fifth, or [[Maitreya]] [[Buddha]], will come after the final [[disappearance]] of the fifth race, and when the sixth race will already have been established on [[earth]] for some hundreds of thousands of years. The sixth will come at the beginning of the seventh race, and the seventh towards the close of that race. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | This arrangement will seem, at the first glance, out of [[harmony]] with the general design of {{Wiki|human evolution}}. Here we are in the middle of the fifth race, and yet it is the fourth [[Buddha]] who has been identified with this race, and the fifth will not come till the fifth race is practically [[extinct]]. The explanation is to be found, however, in the great outlines of the [[esoteric]] {{Wiki|cosmogony}}. At the beginning of each great {{Wiki|planetary}} period, when {{Wiki|obscuration}} comes to an end, and the [[human]] tide-wave in its progress round the chain of [[worlds]] arrives at the shore of a {{Wiki|globe}} where no [[humanity]] has existed for milliards of years, a [[teacher]] is required from the first for the new crop of mankind about to spring up. Remember that the preliminary [[evolution]] of the mineral, vegetable, and [[animal]] {{Wiki|kingdoms}} has been accomplished in [[preparation]] for the new round period. | |

| − | + | With the first infusion of the life-current into the “missing link” {{Wiki|species}} the first race of the new series will begin to evolve it is then that the [[Being]], who may be considered the [[Buddha]] of the first race, appears. The {{Wiki|planetary}} [[spirit]];, or Dhyan (Chohan, who is — or, to avoid the suggestion of an erroneous [[idea]] by the use of a singular verb, let us defy [[grammar]] and say, who are — [[Buddha]] in all his or their developments, [[incarnates]] among the young, innocent, teachable forerunners of the new [[humanity]], and impresses the first broad {{Wiki|principles}} of right and wrong and the first [[truths]] of the [[esoteric]] [[doctrine]] on a sufficient number of receptive [[minds]] to insure the continued reverberation of the [[ideas]] so implanted through successive generations of men in the millions of years to come, before the first race shall have completed its course. It is this advent in the beginning of the round period of [[Divine]] [[Being]] in [[human]] [[form]] that starts the ineradicable {{Wiki|conception}} of the {{Wiki|anthropomorphic}} [[God]] in all [[exoteric]] [[religions]]. | |

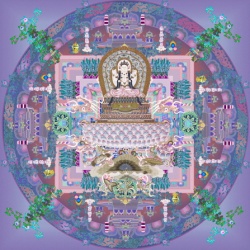

| − | + | The first [[Buddha]] of the series in which [[Gautama Buddha]] stands fourth is thus the second [[incarnation]] of Avaloketiswara, — the {{Wiki|mystic}} [[name]] of the hosts of the [[Dhyan Chohans]], or {{Wiki|planetary}} [[spirits]], belonging to our {{Wiki|planetary}} chain; and though [[Gautama]] is thus the fourth [[incarnation]] of [[enlightenment]] by [[exoteric]] reckoning, he is really the fifth of the true series, and thus properly belonging to our fifth race. | |

| − | + | Avaloketiswara, as just stated, is the {{Wiki|mystic}} [[name]] of the hosts of the [[Dhyan Chohans]]; the proper meaning of the [[word]] is [[manifested]] [[wisdom]], just as Addi-Buddha and [[Amitabha]] both mean abstract [[wisdom]]. | |

| − | These explanations constitute but a sketch of the whole position. I do not possess the arguments nor the literary leisure which would be required for its amplification into a finished picture of the relations which really subsist between the inner principles of Hinduism and those of Buddhism. And I am quite alive to the possibility that many learned and painstaking students of the subject will have formed, as the consequences of prolonged and erudite research, conclusions with which the explanations I am now enabled to give may seem at first sight to conflict. But none the less are these explanations directly gathered from authorities to whom the subject is no less familiar in its scholarly than in its esoteric aspect. And their inner knowledge throws a light upon the whole position which wholly exempts them from the danger of misconstruing texts and mistaking the bearings of obscure symbology. To know when Gautama Buddha was born, what is recorded of his teaching, and what popular legends have gathered round his biography is to know next to nothing of the real Buddha, so much greater than either the historical moral teacher or the fantastic demi-god of tradition. And it is only when we have comprehended the link between Buddhism and Brahmanism that the greatness of the esoteric doctrine rises into its true proportions. | + | The [[doctrine]], as quoted by Mr. Davids, that — “every [[earthly]] {{Wiki|mortal}} [[Buddha]] has his [[pure]] and glorious counterpart in the {{Wiki|mystic}} [[world]], free from the debasing [[conditions]] of this material [[life]], or rather that the [[Buddha]] under material [[conditions]] is only an [[appearance]], the {{Wiki|reflection}}, or [[emanation]], or type of a [[Dhyani Buddha]],” is perfectly correct. |

| + | |||

| + | The number of [[Dhyani Buddhas]], or [[Dhyan Chohans]], or {{Wiki|planetary}} [[spirits]], perfected [[human]] [[spirits]] of former [[world]] periods, is [[infinite]], but only five are practically identified in [[exoteric]] and seven in [[esoteric]] [[teaching]]; and this identification, be it remembered, is a [[manner]] of {{Wiki|speaking}} which must not be interpreted too literally, for there is a {{Wiki|unity}} in the [[sublime]] spirit-life in question that leaves no room for the isolation of [[individuality]]. All this will be seen to harmonize perfectly with the revelations concerning [[Nature]] [[embodied]] in previous chapters, and need not in any way be attributed to {{Wiki|mystic}} imaginings. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Dhyani Buddhas]], or [[Dhyan Chohans]], are the perfected [[humanity]] of previous Manwantaric epochs, and their collective {{Wiki|intelligence}} is described by the [[name]] “Addi-Buddha,” which Mr. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}} is mistaken; in treating as a comparatively recent invention of the [[Northern]] [[Buddhist]]. Addi-Buddha means [[primordial wisdom]], and is mentioned in the oldest [[Sanskrit]] [[books]]. For example, in the [[philosophical]] {{Wiki|dissertation}} on the “ [[Mandukya]] [[Upanishad]],” by Gowdapatha, a [[Sanskrit]] author contemporary with [[Buddha]] himself, the expression is freely used and expounded in exact accordance with the {{Wiki|present}} statement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A [[friend]] of mine in [[India]], a [[Brahmin]] [[pundit]] of first-rate [[attainments]] as a [[Sanskrit]] [[scholar]], has shown me a copy of this [[book]], which has never yet, that he [[knows]] of, been translated into English, and has pointed out a sentence bearing on the {{Wiki|present}} question, giving me the following translation: “{{Wiki|Prakriti}} itself, in fact, is Addi-Buddha, and all the [[Dharmas]] have been [[existing]] from {{Wiki|eternity}}.” Gowdapatha is a [[philosophical]] writer respected by all [[Hindu]] and [[Buddhist]] sects alike, and widely known. He was the [[guru]], or [[spiritual]] [[teacher]] of the first [[Sankaracharya]], of whom I shall have to speak more at length very shortly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Adeptship, when [[Buddha]] [[incarnated]], was not the condensed, compact {{Wiki|hierarchy}} that it has since become under his [[influence]]. There has never been an age of the [[world]] without its {{Wiki|adepts}}; but they have sometimes been scattered throughout the [[world]]; they have sometimes been isolated in separate seclusions; they have gravitated now to this country, now to that; and finally, be it remembered, their [[knowledge]] and [[power]] has not always been inspired with the elevated and severe [[morality]] which [[Buddha]] [[infused]] into its latest and [[highest]] [[organization]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The reform of the [[occult]] [[world]] by his instrumentality was, in fact, the result of his great {{Wiki|sacrifice}}; of the self-denial which induced him to reject the blessed [[condition]] of [[Nirvana]] to which, after his earth-life as [[Buddha]], he was fully entitled, and undertake the [[burden]] of renewed [[incarnations]] in [[order]] to carry out more thoroughly the task he had taken in hand, and confer a correspondingly increased [[benefit]] on mankind. [[Buddha]] re-incarnated himself, next after his [[existence]] as [[Gautama Buddha]], in the [[person]] of the great [[teacher]] of whom but little is said in [[exoteric]] works on [[Buddhism]], but without a [[consideration]] of whose [[life]] it would be impossible to get a correct {{Wiki|conception}} of the position in the Eastern [[world]] of [[esoteric]] [[science]], — namely, [[Sankaracharya]]. The [[latter]] part of this [[name]], it may be explained— [[acharya]] — merely means [[teacher]]. The whole [[name]] as a title is perpetuated to this day under curious circumstances, but the {{Wiki|modern}} bearers of it are not in the direct line of [[Buddhist]] [[spiritual]] [[incarnations]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Sankaracharya]] appeared in [[India]] — no [[attention]] [[being]] paid to his [[birth]], which appears to have taken place on the Malabar coast — about sixty years after [[Gautama]] [[Buddha’s]] [[death]]. [[Esoteric]] [[teaching]] is to the effect that [[Sankaracharya]] simply was [[Buddha]] in all respects, in a new [[body]]. This [[view]] will not be acceptable to uninitiated [[Hindu]] authorities, who attribute a later date to Sankaracharya’s [[appearance]], and regard him as a wholly {{Wiki|independent}} [[teacher]], even inimical to [[Buddhism]], but none the less is the statement just made the {{Wiki|real}} opinion of [[initiates]] in [[esoteric]] [[science]], whether these call themselves [[Buddhists]] or [[Hindus]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I have received the [[information]] I am now giving from a [[Brahmin]] Adwaiti, of Southern [[India]], — not directly from my [[Tibetan]] instructor, — and all [[initiated]] [[Brahmins]], he assures me, would say the same. Some of the later [[incarnations]] of [[Buddha]] are described differently as over-shadowings by the [[spirit]] of [[Buddha]], but in the [[person]] of [[Sankaracharya]] he reappeared on [[earth]]. [[The object]] he had in [[view]] was to fill up some gaps and repair certain errors in his [[own]] previous [[teaching]]; for there is no contention in esotoric [[Buddhism]] that even a [[Buddha]] can be absolutely infallible at every [[moment]] of his career. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The position was as follows: Up to the [[time]] of [[Buddha]], the [[Brahmins]] of [[India]] had jealously reserved [[occult]] [[knowledge]] as the appanage of their [[own]] [[caste]]. Exceptions were oocasionally made in favor of Tshatryas, but the {{Wiki|rule}} was exclusive in a very high [[degree]]. This {{Wiki|rule}} [[Buddha]] broke down, admitting all [[castes]] equally to the [[path]] of adeptship. The change may have been perfectly right in [[principle]], but it paved the way for a great deal of trouble, and as the [[Brahmins]] [[conceived]] for the degradation of [[occult]] [[knowledge]] itself; that is to say, its [[transfer]] to unworthy hands, — not unworthy merely because of [[caste]] {{Wiki|inferiority}}, but because of the [[moral]] {{Wiki|inferiority}} which they [[conceived]] to be introduced into the [[occult]] [[fraternity]], together with brothers of low [[birth]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Brahmin]] contention would not by any means be that because a man should be a [[Brahmin]] it followed that he was necessarily [[virtuous]] and trustworthy; but the argument would be: It is supremely necessary to keep out all but the [[virtuous]] and trustworthy from the secrete and [[powers]] of [[initiation]]. To that end it is necessary not only to set up all the ordeals, probations, and tests we can think of, but also to take no candidates except from the class which, on the whole, by [[reason]] of its [[Wikipedia:Heredity|hereditary]] advantages, is likely to be the best nursery of fit candidates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later [[experience]] is held on all hands now to have gone far towards vindicating the [[Brahmin]] [[apprehension]], and the next [[incarnation]] of [[Buddha]], after that in the [[person]] of [[Sankaracharya]], was a {{Wiki|practical}} admission of this; but meanwhile, In the [[person]] of [[Sankaracharya]], [[Buddha]] was engaged in smoothing over, beforehand, the {{Wiki|sectarian}} strife in [[India]] which be saw impending. The active [[opposition]] of the [[Brahmins]] against [[Buddhism]] began in Asoka’s [[time]], when the great efforts made by that [[ruler]] to spread [[Buddhism]] provoked an [[apprehension]] on their part in reference to their {{Wiki|social}} and {{Wiki|political}} ascendency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It must be remembered that [[initiates]] are not wholly free in all cases from the prejudices of their [[own]] individualities. They possess some such god-like [[attributes]] that outsiders, when they first begin to understand something, of these, are apt to divest them, in [[imagination]], even too completely of [[human]] frailties. [[Initiation]] and [[occult]] [[knowledge]] held in common is certainly a bond of union among {{Wiki|adepts}} of all nationalities, which is far stronger than any other bond. But it has been found on more occasions than one to fail in obliterating all other {{Wiki|distinctions}}. [[Thus]] the [[Buddhist]] and [[Brahmin]] [[initiates]] of the period referred to were by no means of one [[mind]] on all questions, and the [[Brahmins]] very decidedly disapproved of the [[Buddhist]] reformation in its [[exoteric]] aspects. [[Chandragupta]], Asoka’s grandfather, was an upstart, and the [[family]] were [[Sudras]]. This was enough to render his [[Buddhist]] policy unattractive to the representatives of the {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[Brahmin]] [[faith]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The struggle assumed a very embittered [[form]], though ordinary {{Wiki|history}} gives us few or no particulars. The party of primitive [[Buddhism]] was entirely worsted, and the [[Brahmin]] ascendency completely reestablished in the [[time]] of [[Vikramaditya]], about 80 B.C. But [[Sankaracharya]] had traveled all over [[India]] in advance of the great struggle, and had established various mathams, or schools of [[philosophy]], in several important centres. He was only engaged in this task for a few years, but the [[influence]] of his [[teaching]] has been so stupendous that its very magnitude disguises the change wrought. He brought [[exoteric]] [[Hinduism]] into {{Wiki|practical}} [[harmony]] with the [[esoteric]] “[[wisdom]] [[religion]],” and left the [[people]] amusing themselves still with their {{Wiki|ancient}} {{Wiki|mythologies}}, but leaning on [[philosophical]] guides who were [[esoteric]] [[Buddhists]] to all intents and purposes, though in reconciliation with all that was ineradicable in [[Brahmanism]]. The great fault of previous [[exoteric]] [[Hinduism]] lay in its [[attachment]] to vain {{Wiki|ceremonial}} and its adhesion to idolatrous conceptions of the [[divinities]] of the [[Hindu]] {{Wiki|pantheon}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Sankaracharya]] emphasized, by his commentaries on the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, and by his original writings, the necessity of pursuing gnyanam in [[order]] to obtain [[moksha]]; that is to say, the importance of the secret [[knowledge]] to [[spiritual]] progress, and the consummation thereof. He was the founder of the [[Vedantin]] system, — the proper meaning of [[Vedanta]] [[being]] the final end or {{Wiki|crown}} of [[knowledge]], — though the sanctions of that system are derived by him from the writings of [[Vyasa]], the author of the “{{Wiki|Mahabharata}},” the “{{Wiki|Puranas}},” and the “Brahmasutras.” I make these statements, the reader will understand, not on the basis of any researches of my [[own]], — which I am not {{Wiki|Oriental}} [[scholar]] enough to attempt, — but on the authority of a [[Brahmin]] [[initiate]] who is himself a first-rate [[Sanskrit]] [[scholar]] as well as an [[occultist]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Vedantin]] school at {{Wiki|present}} is almost coextensive with [[Hinduism]], making allowance, of course, for the [[existence]] of some special sects like the {{Wiki|Sikhs}}, the Vallabacharyas, or {{Wiki|Maharajah}} [[sect]], of very unfair [[fame]], and may be divided into three great divisions, — the Adwaitees, the Vishishta Adwaitees, and the Dwaitees. The outline of the [[Adwaitee]] [[doctrine]] is that brahmum or [[purush]], the [[universal]] [[spirit]], acts only through [[prakriti]], {{Wiki|matter}}; that everything takes place in this way through the [[inherent]] [[energy]] of {{Wiki|matter}}. Brahmum, or [[Parabrahm]], is thus a passive, incomprehensible, [[unconscious]] [[principle]], but the [[essence]], one [[life]], or [[energy]] of the [[universe]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this way the [[doctrine]] is [[identical]] with the [[transcendental]] {{Wiki|materialism}} of the {{Wiki|adept}} [[esoteric]] [[Buddhist philosophy]]. The [[name]] [[Adwaitee]] {{Wiki|signifies}} not dual, and has reference partly to the [[non-duality]] or {{Wiki|unity}} of [[universal]] [[spirit]], or [[Buddhist]] one [[life]], as {{Wiki|distinguished}} from the notion of its operation through {{Wiki|anthropomorphic}} [[emanations]]; partly to the {{Wiki|unity}} of the [[universal]] and the [[human]] [[spirit]]. As a natural consequence of this [[doctrine]], the Adwaitees infer the [[Buddhist doctrine]] of [[Karma]], regarding the {{Wiki|future}} [[destiny]] of man as altogether depending on the [[causes]] he himself engenders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Vishishta Adwaitees modify these [[views]] by the interpolation of [[Vishnu]] as a [[conscious]] [[deity]], the [[primary]] [[emanation]] of [[Parabrahm]], [[Vishnu]] [[being]] regarded as a personal [[god]], capable of intervening in the course of [[human]] [[destiny]]. They do not regard yog, or [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|training}}, as the proper avenue to [[spiritual]] [[achievement]], but [[conceive]] this to be possible chiefly by means of [[Bhakti]], or devoutness. Roughly stated in the {{Wiki|phraseology}} of {{Wiki|European}} {{Wiki|theology}}, the [[Adwaitee]] may thus be said to believe only in {{Wiki|salvation}} by works, the Vishishta [[Adwaitee]] in {{Wiki|salvation}} by grace. The Dwaitee differs but little from the Vishishta [[Adwaitee]], merely [[affirming]], by the designation he assumes, with increased {{Wiki|emphasis}}, the [[duality]] of the [[human]] [[spirit]] and the [[highest]] [[principle]] of the [[universe]], and [[including]] many {{Wiki|ceremonial}} observances as an [[essential]] part of [[Bhakti]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But all these differences of [[view]], it must be borne in [[mind]], have to do merely with the [[exoteric]] variations on the fundamental [[idea]], introduced by different [[teachers]] with varying [[impressions]] as to the capacity of the populace for assimilating [[transcendental]] [[ideas]]. All leaders of [[Vedantin]] [[thought]] look up to [[Sankaracharya]] and the Mathams he established with the greatest possible reverence, and their inner [[faith]] runs up in all cases into the one [[esoteric]] [[doctrine]]. In fact, the [[initiates]] of all schools in [[India]] interlace with one another. Except as regards {{Wiki|nomenclature}}, the whole system of {{Wiki|cosmogony}} as held by the Buddhist-Arhats, and as set forth in this volume, is equally held by [[initiated]] [[Brahmins]], and has been equally held by them since before [[Buddha’s]] [[birth]]. Whence did they obtain it? the reader may ask. Their answer would be, From the {{Wiki|Planetary}} [[Spirit]], or Dhyan Chohan, who first visited this {{Wiki|planet}} at the dawn of the [[human]] race in the {{Wiki|present}} round period, —more millions of years ago than I like to mention on the basis of conjecture, while the {{Wiki|real}} exact number is withheld. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Sankaracharya]] founded four [[principal]] Mathams: one at Sringari, in Southern [[India]], which has always remained the most important; one at Juggernath, in {{Wiki|Orissa}}; one at Dwaraka, in Kathiawar; and one at Gungotri, on the slopes of the [[Himalayas]] in the [[North]]. The chief of the Sringari [[temple]] has always borne the designation [[Sankaracharya]], in addition to some {{Wiki|individual}} [[name]]. From these four centres others have been established, and Mathams now [[exist]] all over [[India]], exercising the utmost possible [[influence]] on [[Hinduism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I have said that [[Buddha]], by his third [[incarnation]], [[recognized]] the fact that he had, in the excessive [[confidence]] of his [[loving]] [[trust]] in the perfectibility of [[humanity]], opened the doors of the [[occult]] [[sanctuary]] too widely. His third, [[appearance]] was in the [[person]] of [[Tsong-kha-pa]] the great [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|adept}} reformer of the fourteenth century. In this [[personality]] he was. exclusively concerned with the affairs of the {{Wiki|adept}} [[fraternity]], by that [[time]] collecting chiefly in [[Tibet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From [[time]] immemorial there had been a certain secret region in [[Tibet]], which to this day is quite unknown to and unapproachable by any but [[initiated]] persons, and inaccessible to the [[ordinary people]] of the country as to any others, in which {{Wiki|adepts}} have always congregated. But the country generally was not in [[Buddha’s]] [[time]], as it has since become, the chosen habitation of the great brotherhood. Much more than they are at {{Wiki|present}} were the [[Mahatma]] in former times distributed about the [[world]]. The progress of {{Wiki|civilization}}, engendering the {{Wiki|magnetism}} they find so trying, had, however, by the date with which we are now dealing — the fourteenth century — already given rise to a very general {{Wiki|movement}} towards [[Tibet]] on the part of the previously dissociated [[occultists]]. Far more widely than was held to be consistent with the safety of mankind was [[occult]] [[knowledge]] and [[power]] then found to be disseminated. To the task of putting it under the control of a rigid system of {{Wiki|rule}} and law did [[Tsong-kha-pa]] address himself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Without reestablishing the system on the previous unreasonable basis of [[caste]] exclusiveness, he elaborated a code of {{Wiki|rules}} for the guidance of the {{Wiki|adepts}}, the effect of which was to weed out of the [[occult]] [[body]] all but those who sought [[occult]] [[knowledge]] in a [[spirit]] of the most [[sublime]] [[devotion]] to the [[highest]] [[moral]] {{Wiki|principles}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An article in the “{{Wiki|Theosophist}}” for March, 1882, on “Re-incarnations in [[Tibet]],” for the complete [[trustworthiness]] of which in all its {{Wiki|mystic}} bearings I have the [[highest]] assurance, gives a great deal of important [[information]] about the branch of the [[subject]] with which we are now engaged, and the relations between [[esoteric]] [[Buddhism]] and [[Tibet]], which cannot be examined too closely by any one who [[desires]] an exhaustive [[comprehension]] of [[Buddhism]] in its {{Wiki|real}} signification. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The regular system,” we read, “of the Lamaic [[incarnations]] of ‘Sangyas’(or [[Buddha]]) began with [[Tsong-kha-pa]]. This reformer is not the [[incarnation]] of one of the five [[celestial]] Dhyans, or [[heavenly]] [[Buddhas]], as is generally supposed, said to have been created by [[Sakya]] Muni after he had risen to [[Nirvana]], but that of [[Amita]], one of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} names for [[Buddha]]. The records preserved in the | ||

| + | Gon-pa ([[lamasery]]) of Tda-shi Hlum-po (spelt by the English Teshu Lumbo) show that Sangyas [[incarnated]] himself in [[Tsong-kha-pa]], in consequence of the great degradation his [[doctrines]] had fallen into. Until then there had been no other [[incarnations]] than those of the five [[celestial]] [[Buddhas]] and of their Buddhisatvas, each of the former having created (read overshadowed with his [[spiritual]] [[wisdom]]) five of the last named. . . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was because, among many other reforms, [[Tsong-kha-pa]] forbade {{Wiki|necromancy}} (which is practiced to this day, with the most disgusting [[rites]], by the Bhöns, — the aborigines of [[Tibet]], with whom the [[Red]] Caps, or Shammars, had always fraternized) that the [[latter]] resisted his authority. This act was followed by a split between the two sects. Separating entirely from the Gyalukpas, the Dugpas ([[Red]] Caps), from the first in a great minority, settled in various parts of [[Tibet]], chiefly its borderlands, and principally in [[Nepaul]] and Bhootan. But, while they retained a sort of {{Wiki|independence}} at the [[monastery]] of Sakia-Djong, the [[Tibetan]] residence of their [[spiritual]] (?) chief, Gong-sso Rimbo-chay, the Bhootanese have been from their beginning the tributaries and vassals of the [[Dalai]] [[Lamas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The Tda-shi [[Lamas]] were always more powerful and more highly considered than the [[Dalai]] [[Lamas]]. The [[latter]] are the creation of the Tda-shi [[Lama]], Nabang-lob-sang, the sixth [[incarnation]] of [[Tsong-kha-pa]], himself an [[incarnation]] of [[Amitabha]], or [[Buddha]].” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several writers on [[Buddhism]] have entertained a {{Wiki|theory}}, which Mr. Clements [[Markham]] formulates very fully in his “{{Wiki|Narrative}} of the [[Mission]] of [[George Bogle]] to [[Tibet]],” that whereas the original [[scriptures]] of [[Buddhism]] were taken to [[Ceylon]] by the son of [[Asoka]], the [[Buddhism]], which found its way into [[Tibet]] from [[India]] and [[China]], was gradually overlaid with a {{Wiki|mass}} of {{Wiki|dogma}} and [[metaphysical]] speculation. And {{Wiki|Professor}} {{Wiki|Max Muller}} says; “The most important [[element]] in the [[Buddhist]] reform has always been its {{Wiki|social}} and [[moral]] code, not its [[metaphysical]] theories. That [[moral]] code, taken by itself, is one of the most {{Wiki|perfect}} which the [[world]] has ever known; and it was this [[blessing]] that the introduction of [[Buddhism]] brought into [[Tibet]].” | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The [[blessing]],” says the authoritative article in the “{{Wiki|Theosophist}},” from which I have just been quoting, “has remained and spread all over the country, there [[being]] no kinder, purer-minded, more simple or sin-fearing {{Wiki|nation}} than the [[Tibetans]]. But for all that, the popular [[lamaism]], when compared with the {{Wiki|real}} [[esoteric]] or [[Arahat]] [[Buddhism]] of [[Tibet]], offers a contrast as great as the snow trodden along a road in the valley, to the [[pure]] and undefiled {{Wiki|mass}} which glitters on the top of a high mountain peak.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The fact is that [[Ceylon]] is saturated with [[exoteric]], and [[Tibet]] with [[esoteric]], [[Buddhism]], [[Ceylon]] concerns itself merely or mainly with the {{Wiki|morals}} [[Tibet]], or rather the {{Wiki|adepts}} of [[Tibet]], with the [[science]], of [[Buddhism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These explanations constitute but a sketch of the whole position. I do not possess the arguments nor the {{Wiki|literary}} leisure which would be required for its amplification into a finished picture of the relations which really subsist between the inner {{Wiki|principles}} of [[Hinduism]] and those of [[Buddhism]]. And I am quite alive to the possibility that many learned and painstaking students of the [[subject]] will have formed, as the {{Wiki|consequences}} of prolonged and erudite research, {{Wiki|conclusions}} with which the explanations I am now enabled to give may seem at first [[sight]] to conflict. But none the less are these explanations directly [[gathered]] from authorities to whom the [[subject]] is no less familiar in its [[scholarly]] than in its [[esoteric]] aspect. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And their inner [[knowledge]] throws a [[light]] upon the whole position which wholly exempts them from the [[danger]] of misconstruing texts and mistaking the bearings of obscure symbology. To know when [[Gautama Buddha]] was born, what is recorded of his [[teaching]], and what popular {{Wiki|legends}} have [[gathered]] round his {{Wiki|biography}} is to know next to [[nothing]] of the {{Wiki|real}} [[Buddha]], so much greater than either the historical [[moral]] [[teacher]] or the fantastic [[demi-god]] of [[tradition]]. And it is only when we have comprehended the link between [[Buddhism]] and [[Brahmanism]] that the greatness of the [[esoteric]] [[doctrine]] rises into its true proportions. | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Life and Legends of Buddha]] |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.american-buddha.com/cult.esotericbuddhismsinnett.9.htm www.american-buddha.com] | [http://www.american-buddha.com/cult.esotericbuddhismsinnett.9.htm www.american-buddha.com] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:50, 2 May 2020

In January 1898 an Englishman, W. C. Peppe, digging into a mound on his estate at Pipdihwa just the Indian side of the IndianNepalese border, unearthed a soapstone vase some six inches in height with a brief inscription around its lid. The inscription, written in the Brahmi script and dating from about the second century BCE, was in one of the ancient Indian dialects or Prakrits collectively referred to as Middle Indo-Aryan. The precise interpretation of the inscription remains problematic, but it appears to claim that the vase is 'a receptacle of relics of the Blessed Buddha of the Sakyas'.1 The circumstances of this find and the find itself actually reveal a considerable amount about the nature and long history of what we know today as 'Buddhism'.

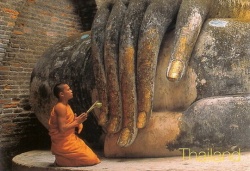

Peppe was among the early excavators of ruined Buddhist stiipas or monumental burial mounds. Such stupas vary considerably in size. The largest were made to enshrine the relics of the Buddha himself or of Buddhist 'saints' or arhats (Pali arahat), while smaller ones contained the remains of more ordinary men and women.2 Today countless stupas are to be found scattered across the Indian subcontinent (where over the past hundred years a few have been restored to something of their former glory) and also other countries where Buddhism spread. Buddhism was, then, in origin an Indian phenomenon. Beginning in the fifth century BCE, its teachings and institutions continued to flourish for some fifteen centuries on Indian soil, inspiring and moulding the intellectual, religious, and cultural life of India.

During this period Buddhism spread via the old trade routes far beyond the confines of India right across Asia, from Afghanistan in the west to Japan in the east, affecting and touching the lives of millions of people. Yet by around the close of the twelfth century Bud" dhist institutions had all but disappeared from India proper, and it is in the countries and cultures that lie beyond India that Buddhism flourishes today. None the less all the variou~ living traditions of Buddhism in some way look back to and revere a figure who has a certain basis in history-a figure who lived and died in northern India several centuries before the beginning of the Christian era and belonged to a people known as the Sakyas (Pali Sakya). He is Sakya-muni, 'the sage of the Sakyas', or as our inscription prefers to call him buddho bhagavii-'the Blessed Buddha', 'the Lord Buddha'. So who, and indeed what, was the Lord Buddha?

This is a quesc tion that might be answered in a number of different ways, a question about which both the Buddhist tradition and the historian have something to say. The nature of the Buddha is a subject that the Buddhist tradition itself has expounded on at length and to which we will return below but, in brief, the word b_uddha is not a name but a title; its meaning is 'one who has woken up'. This title is generally applied by the Buddhist tradition to a class of beings who are, from the perspective of ordinary humanity, extremely rare and quite extraordinary. In contrast to these Buddhas or 'awakened ones' the mass of humanity; along with the other creatures and beings that constitute the world, are asleep-asleep in the sense that they pass through their lives never knowing and seeing the world 'as it is' (yathii-bhutarrt). As a consequence they suffer.

A buddha on the other hand awakens to the knowledge of the world as it truly is and in so doing finds release from suffering. Moreover-and this is perhaps the greatest significance of a buddha for the rest of humanity, and indeed for all the beings who make up the universe-a buddha teaches. He teaches out of sympathy and compassion for the suffering of beings, for the benefit and welfare of all beings; he teaches in order to lead others to awaken to the understanding that brings final relief from suffering. An ancient formula still used in Buddhist devotions today puts it as follows: For the following reasons he is a Blessed One: he is an Arhat, a perfectly and completely awakened one, perfect in his understanding and conduct, happy, one who understands the world, an unsurpassed trainer of unruly men, the teacher of both gods and men, a blessed buddha.3 Such is a buddha in general terms, but what of the particular buddha with whom we started, whose relics appear to have been enshrined in a number of stupas across the north of India and to whom the Buddhist tradition looks as its particular founderthe historical Buddha?

Let us for the moment consider the question not so much from the perspective of the Buddhist tradition as from the perspective of the historian. The Buddha and the Indian 'renouacer' tradition We can know very little of the historical Buddha with any degree of certainty. Yet within the bounds of reasonable historical probability we can form quite a clear picture of the kind of person the Buddha was and the main events of his life. The oldest Buddhist sources, which provide us with a number of details concerning the person and life of the Buddha, date from the fourth or third century BCE. Unfortunately when we tum to the nonBuddhist sources of a similar date, namely the earliest texts of the Jain and brahmanical traditions, there is no explicit mention of the Buddha at all.4 It would be a mistake to conclude, however, that non-Buddhist sources thus provide us with no corroborative evidence for the picture of the Buddha painted in early Buddhist texts.

Essentially the latter present the Buddha as a sramatJa (Pali samaf}a). This term means literally 'one who strives' and belongs to the technical vocabulary of Indian religion, referring as it does to 'one who strives' religiously or spiritually. It points towards a particular tradition that in one way or another has been of great significance in Indian religious history, be it Buddhist, Jain, or Hindu. Any quest for the historical Buddha must begin with the sramatJa tradition. Collectively our sources may not allow us to write the early history of this movement but they do enable us to say a certain amount concerning its character. The tradition is sometimes called the 'renouncer (sarrmyiisin) tradition'. What we are concerned with here is the phenomenon of individuals' renouncing their normal role in society as a member of an extended 'household' in order to devote themselves to some form of religious or spiritual life. The 'renouncer' abandons conventional means of livelihood, such as farming or trade, and adopts instead the religious life as a means of livelihood. That is, he

becomes a religious mendicant dependent on alms. What our sources make clear is that by the fifth century BCE this phenomenon was both widespread and varied. Thus while 'renouncers' had in common the fact .that they had 'gone forth from the household life into homelessness' (to use a phrase common in Buddhist sources), the kind of lifestyle they then adopted was not necessarily the same. This is suggested by some of the terms that we find in the texts: in addition to 'one who strives' and 'renouncer', we fil).d 'wanderer' (parivriijaka/paribbiijaka), 'one who begs his share [of alms)' (bhik(fulbhikkhu), 'naked ascetic' (ace/aka), 'matted-hair ascetic' (jatila), as well as a number of other terms.5

Some of these wanderers and ascetics seem to have been loners, while others seem to have organized themselves into groups and lived under a teacher. Early renouncers seem to· have been for the most part male, although with the growth of Buddhism and Jainism it is certainly the case that women too began to be numbered among. their ranks.

Three kinds of activity seem to have preoccupied these wanderers and. ascetics. First, there is the practice of austerities, such as going naked in all weathers, enduring all physical discomforts, fasting, or undertaking the vow to live like a cow or . even a dog.6 Secondly, there is the cultivation of meditative and contemplative techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as 'altered states of consciousness'.

In the technical vocabulary of Indian religious texts such states come to be termed 'meditations' (dhyiina/jhiina) or 'concentrations' (samiidhi); the attainment of such states of consciousness was generally regarded as bringing the practitioner to some deeper knowledge and experience of the nature of the world. Lastly there is the development of various philosophical views providing the intellectual justification for particular practices and the theoretical expression of the 'knowledge' to which they led. While some groups and individuals seem to have combined all three activities, others favoured one at the expense of the others, and the line between th'e practice of austerities and the practice of meditation may not always be clear: the practice of extreme austerity will certainly alter one's state of mind.

The existence of some of these different groups of ancient Indian wanderers and ascetics with their various practices and theories finds expression in Buddhist texts in a stock description of 'six teachers of other schools', who are each represented as expounding a particular teaching and practice. Another list, with no details of the associated teachings and practices, gives ten types of renouncer. In fact two other ancient Indian traditions that were subsequently of some importance in the religious life of India (the Ajivikas and the Jains) find a place in both these ancient Buddhist lists; the Jain tradition, of course, survives to this day.7 But one of the most significant groups for the understanding of the religious milieu of the historical Buddha is omitted from these lists; this is the early brahmanical tradition. To explain who the · brahmins ( briihma1Ja) were requires a brief excursus into the early evolution of Indian culture and society.

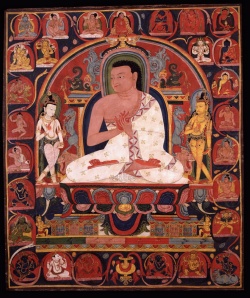

THE historical Buddha, as known to the custodians of the Esoteric Doctrine, is a personage whose birth is not invested with the quaint marvels popular story has crowded round it. Nor was his progress to adeptship traced by the literal occurrence of the supernatural struggles depicted in symbolic legend. On the other hand, the incarnation, which may outwardly be described as the birth of Buddha, is certainly not regarded by occult science as an event like any other birth, nor the spiritual development through which Buddha passed during his earth-life a mere process of intellectual evolution, like the mental history of any other philosopher.

The mistake which ordinary European writers make in dealing with a problem of this sort lies in their inclination to treat exoteric legend either as a record of a miracle about which no more need be said, or as pure myth, putting merely a fantastic decoration on a remarkable life. This, it is assumed, however remarkable, must have been lived according to the theories of Nature at present accepted by the nineteenth century. The account which has now been given in the foregoing pages may prepare the way for a statement as to what the Esoteric Doctrine teaches concerning the real Buddha, who was born, as modern investigation has quite correctly ascertained, 648 years before the Christian era, at Kapila-Vastu near Benares.

Exoteric conceptions, knowing nothing of the laws which govern the operations of Nature in her higher departments, can only explain an abnormal dignity attaching to some particular birth by supposing that the physical body of the person concerned was generated in a miraculous manner. Hence the popular notion about Buddha, that his incarnation in this world was due to an immaculate conception. Occult science knows nothing of any process for the production of a physical human child other than that appointed by physical laws; but it does know a good deal concerning the limits within which the progressive “one life,” or “spiritual monad,” or continuous thread of a series of incarnations, may select definite child-bodies as their human tenements. By the operation of Karma, in the case of ordinary mankind, this election is made, unconsciously as far as the antecedent, spiritual Ego emerging from Devachan is concerned.

But in those abnormal cases where the one life has already forced it-self into the sixth principle — that is to say, where a man has become an adept, and has the power of guiding his own spiritual Ego, in full consciousness as to what he is about, after he has quitted the body in which he won adept-ship, either temporarily or permanently — it is quite within his power to select his own next incarnation. During life, even, he gets above the Devachanic attraction. He becomes one of the conscious directing powers of the planetary system to which he belongs; and great as this mystery of selected re-incarnation may be, it is not by any means restricted in its application to such extraordinary events as the birth of a Buddha.

It is a phenomenon frequently reproduced by the higher adepts to this day, and while a great deal recounted in popular Oriental mythology is either purely fictitious or entirely symbolical, the re-incarnation of the Dalai and Teshu Lamas in Tibet, at which travelers only laugh for want of the knowledge that might enable them to sift fact from fancy, is a sober scientific achievement. In such cases the adept states beforehand in what child, when and where to be born, he is going to re-incarnate, and he very rarely fails.

We say very rarely, because there are some accidents of physical nature which cannot be entirely guarded against; and it is not absolutely certain that, with all the foresight even an adept may bring to bear upon the matter, the child he may choose to become, in his re-incarnated state, may attain physical maturity successfully. And, meanwhile, in the body, the adept is relatively helpless. Out of the body he is just what he has been ever since he became an adept; but as regards the new body he has chosen to inhabit, he must let it grow up in the ordinary course of Nature, and educate it by ordinary processes, and initiate it by the regular occult method into adeptship, before he has got a body fully ready again for occult work on the physical plane.

All these processes are immensely simplified, it is true, by the peculiar spiritual force working within; but at first, in the child’s body, the adept soul is certainly cramped and embarrassed, and, as ordinary imagination might suggest, very uncomfortable and ill at ease. The situation would be very much misunderstood if the reader were to imagine that re-incarnation of the kind described is a privilege which adepts avail themselves of with pleasure.

Buddha’s birth was a mystery of the kind described, and by the light of what has been said it will be easy to go over the popular story of his miraculous origin, and trace the symbolic references to the facts of the situation in some even of the most grotesque fables. None, for example, can look less promising as an allusion to anything like a scientific fact than the statement that Buddha entered the side of his mother as a young white elephant.

But the white elephant is simply the symbol of adept-ship, — something considered to be a rare and beautiful specimen of its kind. So with other ante-natal legends pointing to the fact that the future child’s body had been chosen as the habitation of a great spirit already endowed with superlative wisdom and goodness. Indra and Brahma came to do homage to the child at his birth; that is to say, the powers of Nature were already in submission to the Spirit within him. The thirty-two signs of a Buddha, which legends describe by means of a ludicrous physical symbolism, are merely the various powers of adept-ship.

The selection of the body known as Siddhartha, and afterwards as Gautama, son of Suddhodana, of Kapila-Vastu, as the human tenement of the enlightened human spirit, who had submitted to incarnation for the sake of teaching mankind, was not one of those rare failures spoken of above; on the contrary, it was a signally successful choice in all respects, and nothing interfered with the accomplishment of adeptship by the Buddha in his new body. The popular narrative of his ascetic struggles and temptations, and of his final attainment of Buddhahood under the Bo-tree, is nothing more, of course, than the exoteric version of his initiation.

From that period onward, his work was of a dual nature; he had to reform and revive the morals of the populace and the science of the adepts, — for adeptship itself is subject to cyclic changes, and in need of periodical impulses. The explanation of this branch of the subject, in plain terms, will not alone be important for its own sake, but will be interesting to all students of exoteric Buddhism, as elucidating some of the puzzling complications of the more abstruse “Northern doctrine.”

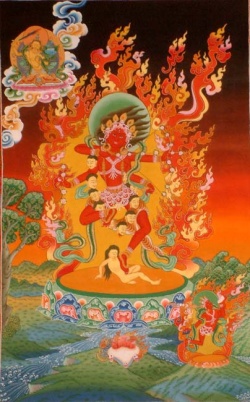

A Buddha visits the earth for each of the seven races of the great planetary period. The Buddha with whom we are occupied was the fourth of the series, and that is why he stands fourth in the list quoted by Mr. Rhys Davids, from Burnouf,—quoted as an illustration of the way the Northern doctrine has been, as Mr. Davids supposes, inflated by metaphysical subtleties and absurdities crowded round the simple morality which sums up Buddhism as presented to the populace. The fifth, or Maitreya Buddha, will come after the final disappearance of the fifth race, and when the sixth race will already have been established on earth for some hundreds of thousands of years. The sixth will come at the beginning of the seventh race, and the seventh towards the close of that race.

This arrangement will seem, at the first glance, out of harmony with the general design of human evolution. Here we are in the middle of the fifth race, and yet it is the fourth Buddha who has been identified with this race, and the fifth will not come till the fifth race is practically extinct. The explanation is to be found, however, in the great outlines of the esoteric cosmogony. At the beginning of each great planetary period, when obscuration comes to an end, and the human tide-wave in its progress round the chain of worlds arrives at the shore of a globe where no humanity has existed for milliards of years, a teacher is required from the first for the new crop of mankind about to spring up. Remember that the preliminary evolution of the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms has been accomplished in preparation for the new round period.

With the first infusion of the life-current into the “missing link” species the first race of the new series will begin to evolve it is then that the Being, who may be considered the Buddha of the first race, appears. The planetary spirit;, or Dhyan (Chohan, who is — or, to avoid the suggestion of an erroneous idea by the use of a singular verb, let us defy grammar and say, who are — Buddha in all his or their developments, incarnates among the young, innocent, teachable forerunners of the new humanity, and impresses the first broad principles of right and wrong and the first truths of the esoteric doctrine on a sufficient number of receptive minds to insure the continued reverberation of the ideas so implanted through successive generations of men in the millions of years to come, before the first race shall have completed its course. It is this advent in the beginning of the round period of Divine Being in human form that starts the ineradicable conception of the anthropomorphic God in all exoteric religions.

The first Buddha of the series in which Gautama Buddha stands fourth is thus the second incarnation of Avaloketiswara, — the mystic name of the hosts of the Dhyan Chohans, or planetary spirits, belonging to our planetary chain; and though Gautama is thus the fourth incarnation of enlightenment by exoteric reckoning, he is really the fifth of the true series, and thus properly belonging to our fifth race.

Avaloketiswara, as just stated, is the mystic name of the hosts of the Dhyan Chohans; the proper meaning of the word is manifested wisdom, just as Addi-Buddha and Amitabha both mean abstract wisdom.

The doctrine, as quoted by Mr. Davids, that — “every earthly mortal Buddha has his pure and glorious counterpart in the mystic world, free from the debasing conditions of this material life, or rather that the Buddha under material conditions is only an appearance, the reflection, or emanation, or type of a Dhyani Buddha,” is perfectly correct.

The number of Dhyani Buddhas, or Dhyan Chohans, or planetary spirits, perfected human spirits of former world periods, is infinite, but only five are practically identified in exoteric and seven in esoteric teaching; and this identification, be it remembered, is a manner of speaking which must not be interpreted too literally, for there is a unity in the sublime spirit-life in question that leaves no room for the isolation of individuality. All this will be seen to harmonize perfectly with the revelations concerning Nature embodied in previous chapters, and need not in any way be attributed to mystic imaginings.

The Dhyani Buddhas, or Dhyan Chohans, are the perfected humanity of previous Manwantaric epochs, and their collective intelligence is described by the name “Addi-Buddha,” which Mr. Rhys Davids is mistaken; in treating as a comparatively recent invention of the Northern Buddhist. Addi-Buddha means primordial wisdom, and is mentioned in the oldest Sanskrit books. For example, in the philosophical dissertation on the “ Mandukya Upanishad,” by Gowdapatha, a Sanskrit author contemporary with Buddha himself, the expression is freely used and expounded in exact accordance with the present statement.

A friend of mine in India, a Brahmin pundit of first-rate attainments as a Sanskrit scholar, has shown me a copy of this book, which has never yet, that he knows of, been translated into English, and has pointed out a sentence bearing on the present question, giving me the following translation: “Prakriti itself, in fact, is Addi-Buddha, and all the Dharmas have been existing from eternity.” Gowdapatha is a philosophical writer respected by all Hindu and Buddhist sects alike, and widely known. He was the guru, or spiritual teacher of the first Sankaracharya, of whom I shall have to speak more at length very shortly.

Adeptship, when Buddha incarnated, was not the condensed, compact hierarchy that it has since become under his influence. There has never been an age of the world without its adepts; but they have sometimes been scattered throughout the world; they have sometimes been isolated in separate seclusions; they have gravitated now to this country, now to that; and finally, be it remembered, their knowledge and power has not always been inspired with the elevated and severe morality which Buddha infused into its latest and highest organization.

The reform of the occult world by his instrumentality was, in fact, the result of his great sacrifice; of the self-denial which induced him to reject the blessed condition of Nirvana to which, after his earth-life as Buddha, he was fully entitled, and undertake the burden of renewed incarnations in order to carry out more thoroughly the task he had taken in hand, and confer a correspondingly increased benefit on mankind. Buddha re-incarnated himself, next after his existence as Gautama Buddha, in the person of the great teacher of whom but little is said in exoteric works on Buddhism, but without a consideration of whose life it would be impossible to get a correct conception of the position in the Eastern world of esoteric science, — namely, Sankaracharya. The latter part of this name, it may be explained— acharya — merely means teacher. The whole name as a title is perpetuated to this day under curious circumstances, but the modern bearers of it are not in the direct line of Buddhist spiritual incarnations.

Sankaracharya appeared in India — no attention being paid to his birth, which appears to have taken place on the Malabar coast — about sixty years after Gautama Buddha’s death. Esoteric teaching is to the effect that Sankaracharya simply was Buddha in all respects, in a new body. This view will not be acceptable to uninitiated Hindu authorities, who attribute a later date to Sankaracharya’s appearance, and regard him as a wholly independent teacher, even inimical to Buddhism, but none the less is the statement just made the real opinion of initiates in esoteric science, whether these call themselves Buddhists or Hindus.

I have received the information I am now giving from a Brahmin Adwaiti, of Southern India, — not directly from my Tibetan instructor, — and all initiated Brahmins, he assures me, would say the same. Some of the later incarnations of Buddha are described differently as over-shadowings by the spirit of Buddha, but in the person of Sankaracharya he reappeared on earth. The object he had in view was to fill up some gaps and repair certain errors in his own previous teaching; for there is no contention in esotoric Buddhism that even a Buddha can be absolutely infallible at every moment of his career.

The position was as follows: Up to the time of Buddha, the Brahmins of India had jealously reserved occult knowledge as the appanage of their own caste. Exceptions were oocasionally made in favor of Tshatryas, but the rule was exclusive in a very high degree. This rule Buddha broke down, admitting all castes equally to the path of adeptship. The change may have been perfectly right in principle, but it paved the way for a great deal of trouble, and as the Brahmins conceived for the degradation of occult knowledge itself; that is to say, its transfer to unworthy hands, — not unworthy merely because of caste inferiority, but because of the moral inferiority which they conceived to be introduced into the occult fraternity, together with brothers of low birth.

The Brahmin contention would not by any means be that because a man should be a Brahmin it followed that he was necessarily virtuous and trustworthy; but the argument would be: It is supremely necessary to keep out all but the virtuous and trustworthy from the secrete and powers of initiation. To that end it is necessary not only to set up all the ordeals, probations, and tests we can think of, but also to take no candidates except from the class which, on the whole, by reason of its hereditary advantages, is likely to be the best nursery of fit candidates.

Later experience is held on all hands now to have gone far towards vindicating the Brahmin apprehension, and the next incarnation of Buddha, after that in the person of Sankaracharya, was a practical admission of this; but meanwhile, In the person of Sankaracharya, Buddha was engaged in smoothing over, beforehand, the sectarian strife in India which be saw impending. The active opposition of the Brahmins against Buddhism began in Asoka’s time, when the great efforts made by that ruler to spread Buddhism provoked an apprehension on their part in reference to their social and political ascendency.

It must be remembered that initiates are not wholly free in all cases from the prejudices of their own individualities. They possess some such god-like attributes that outsiders, when they first begin to understand something, of these, are apt to divest them, in imagination, even too completely of human frailties. Initiation and occult knowledge held in common is certainly a bond of union among adepts of all nationalities, which is far stronger than any other bond. But it has been found on more occasions than one to fail in obliterating all other distinctions. Thus the Buddhist and Brahmin initiates of the period referred to were by no means of one mind on all questions, and the Brahmins very decidedly disapproved of the Buddhist reformation in its exoteric aspects. Chandragupta, Asoka’s grandfather, was an upstart, and the family were Sudras. This was enough to render his Buddhist policy unattractive to the representatives of the orthodox Brahmin faith.

The struggle assumed a very embittered form, though ordinary history gives us few or no particulars. The party of primitive Buddhism was entirely worsted, and the Brahmin ascendency completely reestablished in the time of Vikramaditya, about 80 B.C. But Sankaracharya had traveled all over India in advance of the great struggle, and had established various mathams, or schools of philosophy, in several important centres. He was only engaged in this task for a few years, but the influence of his teaching has been so stupendous that its very magnitude disguises the change wrought. He brought exoteric Hinduism into practical harmony with the esoteric “wisdom religion,” and left the people amusing themselves still with their ancient mythologies, but leaning on philosophical guides who were esoteric Buddhists to all intents and purposes, though in reconciliation with all that was ineradicable in Brahmanism. The great fault of previous exoteric Hinduism lay in its attachment to vain ceremonial and its adhesion to idolatrous conceptions of the divinities of the Hindu pantheon.