Devachan is the man’s own self-conscious personality

IT was not possible to approach a consideration of the states into which the higher human principles pass at death, without first indicating the general framework of the whole design worked out in the course of the evolution of man. That much of my task, however, having now been accomplished, we may pass on to consider the natural destinies of each human Ego in the interval which elapses between the close of one objective life and the commencement of another. At the commencement of another, the Karma of the previous objective life determines the state of life into which the individual shall be born.

This doctrine of Karma is one of the most interesting features of Buddhist philosophy. There has been no secret about it at any time, though for want of a proper comprehension of elements in the philosophy, which have been strictly esoteric, it may sometimes have been misunderstood. Karma is a collective expression applied to that complicated group of affinities for good and evil generated by a human being during life, and the character of which inheres in his fifth principle all through the interval which elapses between his death out of one objective life and his birth into the next. As stated sometimes, the doctrine seems to be one which exacts the notion of a superior spiritual authority summing up the acts of a man’s life at its close, taking into consideration his good deeds and his bad, and giving judgment about him on the whole aspect of the case.

But a comprehension of the way in which the human principles divide up at death, will afford a clue to the comprehension of the way in which Karma operates, and also of the great subject we may better take up first - the immediate spiritual condition of man after death. At death the three lower principles - the body, its mere physical vitality, and its astral counterpart - are finally abandoned by that which really is the Man himself, and the four higher principles escape into that world immediately above our own; above our own, that is, in the order of spirituality - not above it at all, but in it and of it, as regards real locality - the astral plane or kâma loca, according to a very familiar Sanskrit expression. Here a division takes place between the two duads, which the four higher principles include.

The explanation already given concerning the imperfect extent to which the upper principles of man are as yet developed, will show that this estimation of the process, as in the nature of a mechanical separation of the principles, is a rough way of dealing with the matter. It must be modified in the reader’s mind by the light of what has been already said. It may be otherwise described as a trial of the extent to which the fifth principle has been developed. Regarded in the light of the former idea, however, we must conceive the sixth and seventh principles, on the one hand, drawing the fifth, the human soul, in one direction, while the fourth draws it back earthwards in the other.

Now, the fifth principle is a very complex entity, separable itself into superior and inferior elements. In the struggle which takes place between its late companion principles, its best, purest, most elevated and spiritual portions cling to the sixth, its lower instincts, impulses and recollections adhere to the fourth, and it is in a measure torn asunder. The lower remnant, associating itself with the fourth, floats off in the earth’s atmosphere, while the best elements, those, be it understood, which really constitute the Ego of the late earthly personality, the individuality, the consciousness thereof, follow the sixth and seventh into a spiritual condition, the nature of which we are about to examine.

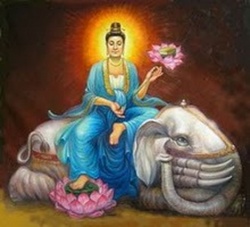

Rejecting the popular English name for this spiritual condition, as encrusted with too many misconceptions to be convenient, let us keep to the Oriental designation of that region or state into which the higher principles of human creatures pass at death. This is additionally desirable because, although the Devachan of Buddhist philosophy corresponds in some respects to the modern European idea of heaven, it differs from heaven in others which are even more important.

Firstly, however, in Devachan, that which survives is not merely the individual monad, which survives through all the changes of the whole evolutionary scheme, and flits from body to body, from planet to planet, and so forth - that which survives in Devachan is the man’s own self-conscious personality, under some restrictions indeed, which we will come to directly, but still it is the same personality as regards its higher feelings, aspirations, affections, and even tastes, as it was on earth. Perhaps it would be better to say the essence of the late self-conscious personality.

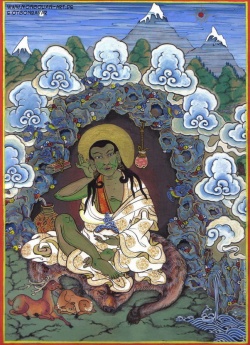

It may be worth the reader’s while to learn what Colonel H S. Olcott has to say in his “Buddhist Catechism” (14th thousand) of the intrinsic difference between “individuality” and “personality.” Since he wrote not only under the approval of the High Priest of the Sripada and Galle, Sumangala, but also under the direct instruction of his Adept Guru, his words will have weight for the student of occultism. This is what he says in his appendix: - “Upon reflection I have submitted ‘personality’ for ‘individuality,’ as written in the first edition. The successive appearances upon one or many earths, or ‘descents into generation’ of the tanhaically coherent parts (Skandas) of a certain being, are a succession of personalities. In each birth the personality differs from that of the previous or next succeeding birth. Karma, the deus ex machinâ, masks (or shall we say, reflects?) itself now in the personality of a sage, again as an artisan, and so on throughout the string of births.

But though personalities ever shift, the one line of life along which they are strung like beads runs unbroken. “It is ever that particular line, never any other. It is therefore individual, an individual vital undulation which began in Nirvana or the subjective side of Nature, as the light or heat undulation through ?¦ther began at its dynamic source; is careering through the objective side of Nature, under the impulse of Karma and the creative direction of Tanha; and tends through many cyclic changes back to Nirvana.

Mr Rhys Davids calls that which passes from personality to personality along the individual chain ‘character’ or ‘doing.’ Since ‘character’ is not a mere metaphysical abstraction, but the sum of one’s mental qualities and moral propensities, would it not help to dispel what Mr Rhys Davids calls ‘the desperate expedient of a mystery,’ if we regarded the life undulation as individuality, and each of its series of natal manifestations as a separate personality?

“The denial of ‘soul’ by Buddha (see ‘Sanyutto Nikaya,’ the Sutta Pitaka) points to the prevalent delusive belief in an independent transmissible personality; and entity that could move from birth to birth unchanged, or go to a place or state where, as such perfect entity, it could eternally enjoy or suffer. And what he shows is that the ‘I am I’ consciousness is, as regards permanency, logically impossible, since its elementary constituents constantly change, and the ‘I’ of one birth differs from the ‘I’ of every other birth. But everything that I have found in Buddhism accords with the theory of a gradual evolution of the perfect man - viz.

A Buddha through numberless natal experiences. And in the consciousness of that person who at the end of a given chain of beings attains Buddha-hood, or who succeeds in attaining the fourth stage of Dhyâna, or mystic self-development, in any one of his births anterior to the final one, the scenes of all these serial births are perceptible. In the ‘Jatakattahavannana,’ so well translated by Mr Rhys Davids, an expression continually recurs which I think rather supports such an idea - viz. ‘Then the blessed one made manifest an occurrence hidden by change of birth,’ or ‘that which had been hidden by, &c.’ Early Buddhism, then, clearly held to a permanency of records in the Akâsa, and the potential capacity of man to read the same when he has evoluted to the stage of true individual enlightenment.”

The purely sensual feelings and tastes of the late personality will drop off from it in Devachan, but it does not follow that nothing is preservable in that state, except feelings and thoughts having a direct reference to religion or spiritual philosophy. On the contrary, all the superior phases, even of sensuous emotion, find their appropriate sphere of development in Devachan. To suggest a whole range of ideas by means of one illustration, a soul in Devachan, if the soul of a man who was passionately devoted to music, would be continuously enraptured by the sensations music produces.

The person whose happiness of the higher sort on earth had been entirely centered in the exercise of the affections will miss none in Devachan of those whom he or she loved. But, at once it will be asked, if some of these are not themselves fit for Devachan, how then? The answer is, that does not matter. For the person who loved them they will be there. It is not necessary to say much more to give a clue to the position. Devachan is a subjective state. It will seem, as real as the chairs and tables round us; and remember that, above all things, to the profound philosophy of occultism are the chairs and tables, and the whole objective scenery of the world, unreal and merely transitory delusions of sense.

As real as the realities of this world to us, and even more so, will be the realities of Devachan to those who go into that state. From this it ensues that the subjective isolation of Devachan, as it will perhaps be conceived at first, is not real isolation at all, as the word is understood on the physical plane of existence; it is companionship with all that the true soul craves for, whether persons, things, or knowledge. An a patient consideration of the place in Nature which Devachan occupies will show that this subjective isolation of each human unit is the only condition which renders possible anything which can be described as a felicitous spiritual existence after death for mankind at large, and Devachan is as much a purely and absolutely felicitous condition for all who attain it, as Avitchi is the reverse of it.

There is no inequality or injustice in the system; Devachan is by no means the same thing for the good and the indifferent alike, but it is not a life of responsibility, and therefore there is no logical place for it for suffering, any more than in Avitchi there is any room for enjoyment or repentance. It is a life of effects, not of causes; a life of being paid your earnings, not of labouring for them. Therefore it is impossible to be during that life cognizant of what is going on on earth. Under the operation of such cognition there would be no true happiness possible in the state after death. A heaven which constituted a watch-tower, from which the occupants could still survey the miseries of the earth, would really be a place of acute mental suffering for its most sympathetic, unselfish, and meritorious inhabitants.

If we invest them in imagination with such a very limited range of sympathy that they could be imagined as not caring about the spectacle of suffering after the few persons to whom they were immediately attached had died and joined them, still they would have a very unhappy period of waiting to go through before survivors reached the end of an often long and toilsome existence below. And even this hypothesis would be further vitiated by making heaven most painful for occupants who were most unselfish and sympathetic, whose reflected distress would thus continue on behalf of the afflicted race of mankind generally, even after their personal kindred had been rescued by the lapse of time.

The only escape from this dilemma lies in the supposition that heaven is not yet opened for business, so to speak, and that all people who have ever lived from Adam downwards are still lying in a death-like trance, waiting for the resurrection at the end of the world. This hypothesis also has its embarrassments, but we are concerned at present with the scientific harmony of esoteric Buddhism, not with the theories of other creeds. Readers, however, who may grant that a purview of earthly life from heaven would render happiness in heaven impossible, may still doubt whether true happiness is possible in the state, as it may be objected, of monotonous isolation now described.

The objection is merely raised from the point of view of an imagination that cannot escape from its present surroundings. To begin with, about monotony. No one will complain of having experienced monotony during the minute, or moment, or half-hour, as it may have been of the greatest happiness he may have enjoyed in life. Most people have had some happy moments, at all events, to look back to for the purpose of this comparison; and let us take even one such minute or moment, too short to be open to the least suspicion of monotony, and imagine its sensations immensely prolonged without any external events in progress to mark the lapse of time.

There is no room, in such a condition of things, for the conception of weariness. The unalloyed, unchangeable sensation of intense happiness goes on and on, not for ever, because the causes which have produced it are not infinite themselves, but for very long periods of time, until the efficient impulse has exhausted itself. Nor must it be supposed that there is, so to speak, no change of occupation for souls in Devachan - that any one moment of earthly sensation is selected for exclusive perpetuation. As a teacher of the highest authority on this subject writes: - “There are two fields of causal manifestations - the objective and subjective.

The grosser energies - those which operate in the denser condition of matter - manifest objectively in the next physical life, their outcome being the new personality of each birth marshaling within the grand cycle of the evolving individuality.

It is but the moral and spiritual activities that find their sphere of effects in Devachan. And, thought and fancy being limitless, how can it be argued for one moment that there is anything like monotony in the state of Devachan? Few are the men whose lives were so utterly destitute of feeling, love, or of a more or less intense predilection for some one line of thought as to be made unfit for a proportionate period of Devachanic experience beyond their earthly life. So, for instance, while the vices, physical and sensual attractions, say, of a great philosopher, but a bad friend and a selfish man, may result in the birth of a new and still greater intellect, but at the same time a most miserable man, reaping the Karmic effects of all the causes produced by the ‘old’ being, and whose make-up was inevitable from the pre-ponderating proclivities of that being in the preceding birth, the intermedial period between the two physical births cannot be, in Nature’s exquisitely well-adjusted laws, but a hiatus of unconsciousness.

There can be no such dreary blank as kindly promised, or rather implied, by Christian Protestant theology, to the ‘departed souls,’ which, between death and ‘resurrection,’ have to hang on in space, in mental catalepsy, awaiting the ‘Day of Judgment.’ Causes produced by mental and spiritual energy being far greater and more important than those that are created by physical impulses, their effects have to be, for weal or woe, proportionately as great. Lives on this earth, or other earths, affording no proper field for such effects, and every labourer being entitled to his own harvest, they have to expand in either Devachan or Avitchi.

The lowest states of Devachan interchain with those of Avitchi.] Bacon for instance, whom a poet called ‘The brightest, wisest, meanest of mankind,’might reappear in his next incarnation as a greedy moneygetter, with extraordinary intellectual capacities. But, however great the latter, they would find no proper field in which that particular line of thought, pursued during his previous lifetime by the founder of modern philosophy, could reap all its dues. It would be but the astute lawyer, the corrupt Attorney-General, the ungrateful friend, and the dishonest Lord Chancellor, who might find, led on by his Karma, a congenial new soil in the body of the money-lender, and reappear as a new Shylock. But where would Bacon, the incomparable thinker, with whom philosophical inquiry upon the most profound problems of Nature was his ‘first and last and only love,’ where would this ‘intellectual giant of his race,’ once disrobed of his lower nature, go to?

Have all the effects of that magnificent intellect to vanish and disappear? Certainly not. Thus his moral and spiritual qualities would also have to find a field in which their energies could expand themselves. Devachan is such a field. Hence all the great plans of moral reform, of intellectual research into abstract principles of Nature - all the divine, spiritual aspirations that had so filled the brightest part of his life would, in Devachan, come to fruition; and the abstract entity, known in the preceding birth as Francis Bacon, and that maybe known in its subsequent re-incarnation as a despised usurer - that Bacon’s own creation, his Frankenstein, the son of his Karma - shall in the meanwhile occupy itself in this inner world, also of its own preparation, in enjoying the effects of the grand beneficial spiritual causes sown in life.

It would live a purely and spiritually conscious existence - a dream of realistic vividness - until Karma, being satisfied in that direction, and the ripple of force reaching the edge of its sub-cycle basin, the being should move into its next area of causes, either in this same world or another, according to his stage of progression . . . . Therefore, there is’ a change of occupation,’ a continual change, in Devachan.

For that dreamlife is but the fruition, the harvest-time, of those psychic seed-germs dropped from the tree of physical existence in our moments of dream and hope - fancy-glimpses of bliss and happiness, stifled in an ungrateful social soil, blooming in the rosy dawn of Devachan, and ripening under its ever-fructifying sky. If man had but one single moment of ideal experience, not even then could it be, as erroneously supposed, the indefinite prolongation of that ‘single moment.’ That one note, struck from the lyre of life, would form the key-note of the being’s subjective state, and work out into numberless harmonic tones and semitones of psychic phantasmagoria.

There, all unrealized hopes, aspirations, dreams, become fully realized, and the dreams of the objective become the realities of the subjective existence. And there, behind the curtain of Maya, its vaporous and deceptive appearances are perceived by the Initiate, who has learned the great secret how to penetrate thus deep into the Arcana of Being . . . .” As physical existence has its cumulative intensity from infancy to prime, and its diminishing energy thenceforward to dotage and death, so the dream-life of Devachan is lived correspondentially.

There is the first flutter of psychic life, the attainment of prime, the gradual exhaustion of force passing into conscious lethargy, semi-unconsciousness, oblivion and - not death, but birth! - birth into another personality and the resumption of action which daily begets new congeries of causes that must be worked out in another term of Devachan. “It is not a reality then, it is a mere dream,” objectors will urge; “the soul so bathed in a delusive sensation of enjoyment, which has no reality all the while, is being cheated by Nature, and must encounter a terrible shock when it wakes to its mistake.” But, in the nature of things, it never does or can wake.

The waking from Devachan is its next birth into objective life, and the draught of Lethe has then been taken. Nor as regards the isolation of each soul is there any consciousness of isolation whatever; nor is there ever possibly a parting from its chosen associates. Those associates are not in the nature of companions who may wish to go away, of friends who may tire of the friend that loves them, even if he or she does not tire of them. Love, the creating force, has placed their living image before the personal soul which craves for their presence, and that image will never fly away. On this aspect of the subject I may again avail myself of the language of my teacher:- “Objectors of that kind will be simply postulating an incongruity, an intercourse of entities in Devachan, which applies only to the mutual relationship of physical existence!

Two sympathetic souls, both disembodied, will each work out its own Devachanic sensations, making the other a sharer in its subjective bliss. This will be as real to them, naturally, as though both were yet on this earth. Nevertheless, each is dissociated from the other as regards personal or corporeal association. While the latter is the only one of its kind that is recognized by our earth experience as an actual intercourse, for the Devachanee it would be not only something unreal, but could have no existence for it in any sense, not even as a delusion: a physical body or even a Mâyâvi-rûpa remaining to its spiritual senses as invisible as it is itself to the physical senses of those who loved it best on earth.

Thus even though one of the ‘sharers’ were alive and utterly unconscious of that intercourse in his waking state, still every dealing with him would be to the Devachanee an absolute reality, And what actual companionship could there ever be other than the purely idealistic one, as above described, between two subjective entities which are not even as material as that ethereal body-shadow - the Mâyâvi-rûpa? To object to this on the ground that one is thus ‘cheated by Nature,’ and to call it ‘ a delusive sensation of enjoyment which has no reality,’ is to show oneself utterly unfit to comprehend the conditions of life and being outside of our material existence.

For how can the same distinction be made in Devachan - i.e. outside of the conditions of earth-life - between what we call a reality and a factitious or an artificial counterfeit of the same, in this, our world? The same principle cannot apply to the two sets of conditions. It is conceivable that what we call a reality in our embodied physical state will exist under the same conditions as an actuality for a disembodied entity? On earth, man is dual - in the sense of being a thing of matter and a thing of spirit; hence the natural distinction made by his mind - the analyst of his physical sensations and spiritual perceptions - between an actuality and a fiction; though, even in this life, the two groups of faculties are constantly equilibrating each other, each group when dominant seeing as fiction or delusion what the other believes to be most real.

But in Devachan our Ego has ceased to be dualistic, in the above sense, and becomes a spiritual, mental entity. That which was a fiction, a dream in life, and which had its being but in the region of ‘fancy,’ becomes, under the new conditions of existence, the only possible reality. Thus, for us to postulate the possibility of any other reality for a Devachanee is to maintain an absurdity, a monstrous fallacy, an idea unphilosophical to the last degree. The actual is that which is acted or performed de facto: ‘the reality of a thing is proved by its actuality.’ And the suppositions and artificial having no possible existence in that Devachanic state, the logical sequence is that everything in it is actual and real. For, again, whether overshadowing the five principles during the life of the personality, or entirely separated from the grosser principles by the dissolution of the body - the sixth principle, or our ‘Spiritual Soul,’ has no substance - it is ever Arupa; nor is it confined to one place with a limited horizon of perceptions around it.

Therefore, whether in or out of its mortal body it is ever distinct, and free from its limitations; and if we call its Devachanic experiences ‘a cheating of Nature,’ then we should never be allowed to call ‘reality’ any of those purely abstract feelings that belong entirely to, and are reflected and assimilated by, our higher soul - such, for instance, as an ideal perception of the beautiful, profound philanthropy, love, &c., as well as every other purely spiritual sensation that during life fills our inner being with either immense joy or pain.” We must remember that by the very nature of the system described there are infinite varieties of wellbeing in Devachan, suited to the infinite varieties of merit in mankind. If “the next world” really were the objective heaven which ordinary theology preaches, there would be endless injustice and inaccuracy in its operation.

People, to begin with, would be either admitted or excluded, and the differences of favour shown to different guests within the all-favoured region would not sufficiently provide for differences of merit in this life. But the real heaven of our earth adjusts itself to the needs and merits of each new arrival with unfailing certainty. Not merely as regards the duration of the blissful state, which is determined by the causes engendered during objective life, but as regards the intensity and amplitude of the emotions which constitute that blissful state, the heaven of each person who attains the really existent heaven is precisely fitted to his capacity for enjoying it.

It is the creation of his own aspirations and faculties. More than this it may be impossible for the uninitiated comprehension to realize. But this indication of its character is enough to show how perfectly it falls into its appointed place in the whole scheme of evolution. “Devachan,” to resume my direct quotations, “is, of course, a state, not a locality, as much as Avitchi, its antithesis (which please not to confound with hell). Esoteric Buddhist philosophy has three principal lokas so-called - namely, 1. Kâma loka; 2. Rûpa loka; and 3. Arûpa loka; or in their literal translation and meaning - 1. world of desires or passions, of unsatisfied earthly cravings - the abode of ‘Shells’ and Victims, of Elementaries and Suicides; 2. the world of forms - i.e., of shadows more spiritual, having form and objectivity, but no substance; and 3. the formless world, or rather the world of no form, the incorporeal, since its denizens can have neither body, shape, nor colour for us mortals, and in the sense that we give to these terms.

These are the three spheres of ascending spirituality in which the several groups of subjective and semi-subjective entities find their attractions. All but the suicides and the victims of premature violent deaths go, according to their attractions and powers, either into the Devachanic or the Avitchi state, which two states form the numberless subdivisions of Rûpa and Arûpa lokas - that is to say, that such states not only vary in degree, or in their presentation to the subject entity as regards form, colour, &c., but that there is an infinite scale of such states, in their progressive spirituality and intensity of feeling, from the lowest in the Rûpa, up to the highest and the most exalted in the Arûpa-loka. The student must bear in mind that personality is the synonym for limitation; and that the more selfish, the more contracted the person’s ideas, the closer will he cling to the lower spheres of being, the longer loiter on the plane of selfish social intercourse.”

Devachan being a condition of mere subjective enjoyment, the duration and intensity of which is determined by the merit and spirituality of the earth-life last past, there is no opportunity, while the soul inhabits it, for the punctual requital of evil deeds. But Nature does not content herself with either forgiving sins in a free and easy way, or damning sinners outright, like a lazy master too indolent, rather than too good-natured, to govern his household justly. The Karma of evil, be it great or small, is at certainly operative at the appointed time as the Karma of good. But the place of its operation is not Devachan, but either a new rebirth, or Avitchi - a state to be reached only in exceptional cases and by exceptional natures. In other words, while the common-place sinner will reap the fruits of his evil deeds in a following re-incarnation, the exceptional criminal, the aristocrat of sin, has Avitchi in prospect - that is to say, the condition of subjective spiritual misery which is the reverse side of Devachan.

“Avitchi is a state of the most ideal spiritual wickedness, something akin to the state of Lucifer, so superbly described by Milton. Not many, though, are there who can reach it, as the thoughtful reader will perceive. And if it is urged that since there is Devachan for nearly all, for the good, the bad, and the indifferent, the ends of harmony and equilibrium are frustrated, and the law of retribution and of impartial, implacable justice, hardly met and satisfied by such a comparative scarcity, if not absence of its antithesis, then the answer will show that it is not so. ‘Evil is the dark son of Earth (matter), and Good - the fair daughter of Heaven’ (or Spirit), says the Chinese philosopher; hence the place of punishment for most of our sins is the earth - its birth-place and play-ground.

There is more apparent and relative than actual evil even on earth, and it is not given to the hoi polloi to reach the fatal grandeur and eminence of a ‘Satan’ every day.” Generally the re-birth into objective existence is the event for which the Karma of evil patiently waits; and then it irresistibly asserts itself, not that the Karma of good exhausts itself in Devachan, leaving the unhappy monad to develop a new consciousness with no material beyond the evil deeds of its last personality. The re-birth will be qualified by the merit as well as the demerit of the previous life, but the Devachan existence is a rosy sleep - a peaceful night, with dreams more vivid than day, and imperishable for many centuries. It will be seen that the Devachan state is only one of the conditions of existence which go to make up the whole spiritual or relatively spiritual complement of our earth life. Observers of spiritualistic phenomena would never have been perplexed, as they have been, if there were no other but the Devachan state to be dealt with.

For once in Devachan there is very little opportunity for communication between a spirit, then wholly absorbed in its own sensations and practically oblivious of the earth left behind, and its former friends still living. Whether gone before or yet remaining on earth, those friends, if the bond of affection has been sufficiently strong, will be with the happy spirit still, to all intents and purposes for him, and as happy, blissful, innocent, as the disembodied dreamer himself. It is possible, however, for yet living persons to have visions of Devachan, though such visions are rare, and only one-sided, the entities in Devachan, sighted by the earthly clairvoyant, being quite unconscious themselves of undergoing such observation.

The spirit of the clairvoyant ascends into the condition of Devachan in such rare visions, and thus becomes subject to the vivid delusions of that existence. It is under the impression that the spirits, with which it is in Devachanic bonds of sympathy, have come down to visit earth and itself, while the converse operation has really taken place. The clairvoyant’s spirit has been raised towards those in Devachan. Thus many of the subjective spiritual communications - most of them when the sensitives are pure-minded - are real, though it is most difficult for the uninitiated medium to fix in his mind the true and correct pictures of what he sees and hears.

In the same way some of the phenomena called psychography (though more rarely) are also real. The spirit of the sensitive, getting odylized, so to say, by the aura of the spirit in the Devachan, becomes for a few minutes that departed personality, and writes in the handwriting of the latter, in his language and in his thoughts, as they were during his lifetime. The two spirits become blended in one, and the preponderance of one over the other during such phenomena determines the preponderance of personality in the characteristic exhibited. Thus it may incidentally be observed, what is called rapport, is, in plain fact, an identity of molecular vibration between the astral part of the incarnate medium and the astral part of the disincarnate personality. As already indicated, and as the common sense of the mater would show, there are great varieties of states in Devachan, and each personality drops into its befitting place there.

Thence, consequently he emerges in his befitting place in the world of causes, this earth or another, as the case may be, when his time for re-birth comes. Coupled with survival of the affinities, comprehensively described as Karma, the affinities both for good and evil engendered by the previous life, this process will be seen to accomplish nothing less than an explanation of the problem which has always been regarded as so incomprehensible - the inequalities of life. The conditions on which we enter life are the consequences of the use we have made of our last set of conditions. They do not impede the development of fresh Karma, whatever they may be, for this will be generated by the use we make of them in turn. Nor is it to be supposed that every event of a current life which bestows joy or sorrow is old Karma bearing fruit.

Many may be the immediate consequences of acts in the life to which they belong - ready-money transactions with Nature, so to speak, of which it may be hardly necessary to make any entry in her books. But the great inequalities of life, as regards the start in it which different human beings make, is a manifest consequence of old Karma, the infinite varieties of which always keep up a constant supply of recruits for all the manifold varieties of human condition. It must not be supposed that the real Ego slips instantaneously at death from the earth life and its entanglements, into the Devachanic condition. When the division of, or purification of the fifth principle has been accomplished in Kâma loca by the contending attractions of the fourth and sixth principles, the real Ego passes into a period of unconscious gestation.

I have spoken already of the way in which the Devachanic life is in itself a process of growth, maturity, and decline; but the analogies of earth are even more closely preserved. There is a spiritual ante-natal state at the entrance to spiritual life, as there is a similar and equally unconscious physical state at the entrance to objective life. And this period, in different cases, may be of very different duration - from a few moments to immense periods of years. When a man dies, his soul or fifth principle becomes unconscious and loses all remembrance of things internal as wall as external.

Whether his stay in Kâma loca has to last but a few moments, hours, days, weeks, months or years, whether he dies a natural or a violent death, whether this occurs in youth or age, and whether the Ego has been good, bad, or indifferent, his consciousness leaves him as suddenly as the flame leaves a wick when it is blown out. When life has retired from the last particle of the brain matter, his perceptive faculties become extinct for ever, and his spiritual powers of cognition and volition become for the time being as extinct as the others. His Mâyâvi-rûpa may be thrown into objectivity, as in the case of apparitions after death, but unless it is projected by a conscious or intense desire to see or appear to some one shooting through the dying brain, the apparition will be simply automatic.

The revival of consciousness in Kâma loca is obviously, from what has been said, a phenomenon that depends on the characteristic of the principles passing, unconsciously at the moment, out of the dying body. It may become tolerably complete under circumstances by no means to be desired, or it may be obliterated by a rapid passage into the gestation state leading to Devachan. This gestation state may be of very long duration in proportion to the Ego’s spiritual stamina, and Devachan accounts for the remainder of the period between death and the next physical re-birth.

The whole period is, of course, of very varying length in the case of different persons, but re-birth in less than fifteen hundred years is spoken of as almost impossible, while the stay in Devachan, which rewards a very rich Karma is sometimes said to extend to enormous periods.

The comments I have to make on the doctrine embodied in the foregoing chapter will be postponed most conveniently to the end of the next, and offered in connection with those applying to the conditions of Kâma loca.