Gautama

Gautama - Buddha's family name, or last name. His first name was Siddhartha.

No comprehensive account of Gotama Buddha is as yet possible. The details given in this article are those generally accepted by orthodox Theravādins and contained in their books, chiefly the Pāli Commentaries, more especially the Nidānakathā of the Jātaka and the Buddhavamsa Commentary.

Biographical details are also found in Mahā Vagga and the Culla Vagga of the Vinaya Pitaka, the Buddhavamsa and in various scattered passages of the Nikayas of the Sutta Pitaka. References to these are given where considered useful. Controversy exists with regard to many of the matters mentioned; for discussion of the varying views regarding these, reference should be made to the works of Oldenberg, Rhys Davids (both Professor and Mrs. Rhys Davids), Kern, E. J. Thomas and other scholars. Further particulars of persons and places mentioned can be obtained by reference to the articles under the respective names.

He was a Sākiyan (the Sākiyans were evidently subjects of the Kosala king; the Buddha calls himself a Kosalan, M.ii.124), son of Suddhodana (all Pāli Commentaries and Sanskrit works represent the Buddha as the son of a king, descendant of a long line of famous ancestors), chief ruler of Kapilavatthu, and of Mahā Māyā, Suddhodana’s chief consort, and he belonged to the Gotama-gotta. Before his conception he was in the Tusita heaven, waiting for the due time for his birth in his last existence. Then, having made the “five investigations” (pañcavilolcanāni) (see Buddha), he took leave of his companions and descended to earth. (According to the Lalitavistara he appointed the Bodhisatta Maitreya as king of Tusita in his place). Many wondrous and marvellous events attended his conception and birth. (Given in the Acchariyabbhutadhamma Sutta, M.iii.118f; also D.ii.12f. A more detailed account is found in J. i.47ff; both the Lai. and the Mtu.ii.14ff differ as to the details given here of the conception and the birth).

The conception takes place on the full-moon day of Āsālha, with the moon in Uttarāsālha, and Maya has no relations with her husband. She has a marvellous dream in which the Bodhisatta, as a white elephant, enters her womb through her side. When the dream is mentioned to the brahmins, they foretell the birth of a son who will be either a universal monarch or a Buddha. An earthquake takes place and thirty-two signs appear, presaging the birth of a great being. The first of these signs is a boundless, great light, flooding every corner of the ten thousand worlds; everyone beholds its glory, even the fires in all hells being extinguished. Ten months after the conception, in the month of Visākha, Māyā wishes to visit her parents in Devadaha. On the way thither from Kapilavatthu she passes the beautiful Lumbini grove, in which she desires to wander; she goes to a great sāla-tree and seizes a branch in her hand; labour pains start immediately, and, when the courtiers retire, having drawn a curtain round her, even while standing, she is delivered of the child. It is the day of the full moon of Visākha; four Mahābrahmas receive the babe in a golden net, and streams of water descend from the sky to wash him. The boy stands on the earth, takes seven steps north-wards and utters his lion-roar, “I am the chief in the world.” On the same day seven other beings were born: the Bodhi-tree, Rāhula’s mother (Rāhulamātā, his future wife), the four Treasure-Troves (described at DA.i.284), his elephant, his horse Kanthaka, his charioteer Channa, and Kāludāyī. The babe is escorted back to Kapilavatthu on the day of his birth and his mother dies seven days later.

The isi Asita (or Kāladevala), meditating in the Himālaya, learns from the Tāvatimsa gods of the birth of the Buddha, visits Suddhodana the same day and sees the boy, whom they both worship. Asita weeps for sorrow that he will not live to see the boy’s Buddhahood, but he instructs his nephew Nālaka (v.l. Naradatta) to prepare himself for that great day. On the fifth day after the birth is the ceremony of name-giving. One hundred and eight brahmins are invited to the festival at the palace; eight of them - Rāma, Dhaja, Lakkhana, Manti, Kondañña, Bhoja, Suyāma and Sudatta - are interpreters of bodily marks, and all except Kondañña prophesy two possibilities for the boy; but Kondañña, the youngest, says, quite decisively, that he will be a Buddha. The name given to the boy at this ceremony is not actually mentioned, but from other passages it is inferred that it was Siddhattha (q.v.).

Among other incidents recounted of the Buddha’s boyhood is that of his attaining the first jhāna under a jambu-tree. One day he is taken to the state ploughing of the king where Suddhodana himself, with his golden plough, ploughs with the farmers. The nurses, attracted by the festivities, leave the child under a jambu-tree. They return to find him seated, cross-legged, in a trance, the shadow of the tree remaining still, in order to protect him. The king is informed and, for the second time, does reverence to his son. J. i.57f; MA.i.466f; the incident is alluded to in the Mahā Saccaka Sutta (M.i.246); the corresponding incident recounted in Mtu. (ii.45f.) takes place in a park, and the, details differ completely. The Lai. has two versions, one in prose and one in verse and both resemble the Mtu.; but in these the Buddha is represented as being much older. The Divy (391) and the Tibetan versions (e.g., Rockhill, p.22) put the incident very much later in the Buddha’s life. Other incidents are given in Lai. and Mtu.

The Bodhisatta is reported to have lived in the household for twenty-nine years a life of great luxury and excessive ease, surrounded by all imaginable comforts. He owns three palaces - Ramma, Suramma and Subha - for the three seasons. Mention is made of his luxurious life in A.i.145; also in M.i.504; further details are given in AA.i.378f.; J. i.58. See also Mtu.ii.115; cf. Vin.i.15; D.ii.21.

When the Bodhisatta is sixteen years old, Suddhodana sends messengers to the Sākyans asking that his son be allowed to seek a wife from among their daughters; but the Sākyans are reluctant to send them, for, they say, though the young man is hand-some, he knows no art; how, then, can he support a wife? When this is reported to the prince, he summons an assembly of the Sākyans and performs various feats, chief of these being twelve feats with a bow which needs the strength of one thousand men. (The feats with the bow are described in the Sarabhanga Jātaka, J. v.129f ). The Sākyans are so impressed that each sends him a daughter, the total number so sent being forty thousand. The Bodhisatta appoints as his chief wife the daughter of Suppabuddha, who, later, comes to be called Rāhulamātā. She is known under various names: Bhaddakaccā (or Kaccānā), Yasodharā. Bimbā, Bimbasundarī and Gopā. For a discussion see Rāhulamātā.

According to the generally accepted account, Gotama is twenty-nine when the incidents occur which lead to final renunciation. Following the prophecy of the eight brahmins, his father had taken every precaution that his son should see no sign of old age, sickness or death. But the gods decide that the time is come for the Enlightenment, and instil into Gotama’s heart a desire to go into the park. On the way, the gods put before him a man showing signs of extreme age, and the Bodhisatta returns, filled with desire for renunciation. The king, learning this, surrounds him with even greater attractions, but on two other days Gotama goes to the park and the gods put before him a sick man and a corpse. (According to some accounts, e.g. that of the Dīghabhānakas, the four omens were all seen on the same day, J. i.59)

On the full-moon day of Āsālha, the day appointed for the Great Renunciation, Gotama sees a monk and hears from his charioteer praise of the ascetic life. Feeling very happy, he goes to the park to enjoy himself. Sakka sends Vissakamma himself to bathe and adorn him, and as Gotama returns to the city in all his majesty, he receives news of the birth of his son. Foreseeing in this news a bond, he decides to call the babe Rāhula (q.v.). Kisā Gotamī (q.v.) sees Gotama on the way to the palace and, filled with longing for him, sings to him a song containing the word nibbuta. The significance of the word (=extinguished, at peace) thrills him, and he sends to Kisā his priceless gold necklace which she, however, accepts as a token of love. Gotama enters the palace and sleeps. He wakes in the middle of the night to find his female musicians sleeping in attitudes which fill him with disgust and with loathing for the worldly life, and he decides to leave it. (In some versions the Renunciation takes place seven days after the birth of Rāhula, J. i.62). He orders Channa to saddle Kanthaka, and enters his wife’s room for a last look at her and their son.

He leaves the city on his horse Kanthaka, with Channa clinging to its tail. The devas muffle the sound of the horse’s hoofs and of his neighing and open the city gates for Gotama to pass. Māra appears before Gotama and seeks to stay him with a promise that he shall be universal monarch within seven days. On his offer being refused, Māra threatens to shadow him always. Outside the city, at the spot where later was erected the Kanthakanivattana-cetiya, Gotama turns his horse round to take a last look at Kapilavatthu. It is said that the earth actually turned, to make it easy for him to do so. Then, accompanied by the gods, he rides thirty leagues through three kingdoms - those of the Sākyans, the Koliyans and the Mallas - and his horse crosses the river Anomā in one leap. On the other side, he gives all his ornaments to Channa, and with his sword cuts off hair and beard, throwing them up into the air, where Sakka takes them and enshrines them in the Cūlāmani-cetiya in Tāvatimsa. The Brahmā Ghatikāra offers Gotama the eight requisites of a monk, which he accepts and adopts. He then sends Channa and Kanthaka back to his father, but Kanthaka, broken-hearted, dies on the spot and is reborn as Kanthaka-devaputta.

The account given here is taken mainly from the Nidānakathā (J.i.59ff) and evidently embodies later tradition; cp. D.ii.21ff. From passages found in the Pitakas (e.g., A.i.145; M.i.163, 240; M.ii.212f.) it would appear that the events leading up to the Renunciation were not so dramatic as given here, the process being more gradual. I do not, however, agree with Thomas (op. cit., 58) that, according to these accounts, the Bodhisatta left the world when “quite a boy.” I think the word dahara is used merely to indicate “the prime of youth,” and not necessarily “boyhood.” The description of the Renunciation in the Lal. is very much more elaborate and adds numerous incidents, no account of which is found in the Pāli.

From Anomā the Bodhisatta goes to the mango-grove of Anupiya, and after spending seven days there walks to Rājagaha (a distance of thirty leagues) in one day, and there starts his alms rounds. Bimbisāra’s men, noticing him, report the matter to the king, who sends messengers to enquire who this ascetic is. The men follow Gotama to the foot of the Pandavapabbata, where he eats his meal, and they then go and report to the king. Bimbisāra visits Gotama, and, pleased with his hearing, offers him the sovereignty. On learning the nature of Gotama’s quest, he wins from him a promise to visit Rājagaha first after the Enlightenment.

This incident is also mentioned in the Pabbajjā Sutta (Sn.vv.405-24), but there it is the king who first sees Gotama. It is significant that, when asked his identity, Gotama does not say he is a king’s son. The Pali version of tile sutta contains nothing of Gotama’s promise to visit Rājagaha, but the Mtu. version (ii.198-200), which places the visit later, has two verses, one of which contains the request and the other the acceptance; and the SnA. (ii.385f.), too, mentions the promise and tells that Bimbisāra was informed of the prophecy concerning Gotama. There is another version of the Mtu. (ii.117-20) which says that Gotama went straight to Vaisāli after leaving home, joining Ālāra, and later visited Uddaka at Rājagaha. Here no mention is made of Bimbisāra. We are told in the Mhv. (ii.25ff) that Bimbisāra and Gotama (Siddhattha) had been playmates, Bimbisāra being the younger by five years. Bimbisāra’s father (Bhātī) and Suddhodana were friends.

Journeying from Rājagaha, Gotama in due

course becomes a disciple of Ālāra-Kālāma. Having learnt and practised all that ālāra has to teach, he finds it unsatisfying and joins Uddaka-Rāmaputta; but Uddaka’s doctrine leaves him still unconvinced and he abandons it. He then goes to Senānīgāma in Uruvelā and there, during six years, practises all manner of severe austerities, such as no man had previously undertaken. Once he falls fainting and a deva informs Suddhodana that Gotama is dead. But Suddhodana, relying on the prophecy of Kāladevala, refuses to believe the news. Gotama’s mother, now born as a devaputta in Tāvatimsa, comes to him to encourage him. At Uruvelā, the Pañcavaggiya monks are his companions, but now, having realised the folly of extreme asceticism, he decides to abandon it, and starts again to take normal food; thereupon the Pañcavaggiyas, disappointed, leave him and go to Isipatana.

J.i.66f. The Therīgāthā Commentary

(p.2) mentions another teacher of Gotama, named Bhaggava, whom Gotama visited

before Ālāra. Lal. (330 [264]) contains a very elaborate account of Gotama’s

visits to teachers; he goes first to two brahmin women, Sākī and Padmā, then

to Raivata and Rajaka, son of Trimandika, and finally (as far as this chapter

is concerned) to Ālāra at Vaisāli. A poem containing an account of the meeting

of Gotama with Bimbisāra is inserted into this account. The next chapter tells

of Uddaka. An account of Gotama’s visits to teachers and of the details of his

austerities is also given in the Mahā Saccaka Sutta, already referred to

(M.i.240ff); the Mahā Sīhanāda Sutta (M.i.77ff) contains a long and detailed

account of his extreme asceticisms. See also M.i.163ff; ii.93f.

Gotama’s desire for normal food is satisfied by an offering brought by Sujātā to the Ajapāla banyan tree under which he is seated. She had made a vow to the tree, and her wish having been granted, she takes her slave-girl, Punnā, and goes to the tree prepared to fulfil her promise. They take Gotama to be the Tree-god, come in person to accept her offering of milk-rice; the offering is made in a golden bowl and he takes it joyfully. Five dreams he had the night before convince Gotama that he will that day become the Buddha. (The dreams are, recounted in A.iii.240 and in Mtu.ii.136f). It is the full-moon day of Visākha; he bathes at Suppatittha in the Nerañjarā, eats the food and launches the bowl up stream, where it sinks to the abode of the Nāga king, Kāla (Mahākāla).

Gotama spends the rest of the day in a sāla-grove and, in the evening, goes to the foot of the Bodhi-tree, accompanied by various divinities; there the grass-cutter Sotthiya gives him eight handfuls of grass; these, after investigation, Gotama spreads on the eastern side of the tree, where it becomes a seat fourteen hands long, on which he sits cross-legged, determined not to rise before attaining Enlightenment.

J.i.69. The Pitakas know nothing of Sujātā’s offering or of Sotthiya’s gift. Lal. (334-7 [267-70]) mentions ten girls in all who provide him with food during his austerities. Divy (392) mentions two, Nandā and Nandabalā.

Māra, lord of the world of passion, is determined to prevent this fulfilment, and attacks Gotama with all the strength at his command. His army extends twelve leagues to the front, right, and left of him, to the end of the Cakkavāla behind him, and nine leagues into the sky above him. Māra himself carries numerous weapons and rides the elephant Girimekhala, one hundred and fifty leagues in height. At the sight of him all the divinities gathered at the Bodhi-tree to do honour to Gotama - the great Brahmā, Sakka, the Nāga-king Mahākāla - disappear in a flash, and Gotama is left alone with the ten pāramī, long practised by him, as his sole protection. All Māra’s attempts to frighten him by means of storms and terrifying apparitions fail, and, in the end, Māra hurls at him the Cakkāvudha. It remains as a canopy poised over Gotama. The very earth bears witness to Gotama’s fitness to be the Enlightened One, and Girimekhala kneels before him. Māra is vanquished and flees headlong with his vast army. The various divinities who had fled at the approach of Māra now return to Gotama and exult in his triumph.

The whole story of the contest with Māra is, obviously, a mythological development. It is significant that in the Majjhima passages referred to earlier there is no mention of Māra, of a temptation, or even of a Bodhi-tree; but see D.ii.4 and Thomas (op. cit., n.1). According to the Kālingabodhi Jātaka, which, very probably, embodies an old tradition, the bodhi-tree was worshipped even in the Buddha’s life-time. The Māra legend is, however, to be found in the Canonical Padhāna Sutta of the Sutta Nipāta. This perhaps contains the first suggestion of the legend. For a discussion see Māra.

Gotama spends that night in deep meditation. In the first watch he gains remembrance of his former existences; in the middle watch he attains the divine eye (dibbacakkhu); in the last watch he revolves in his mind the Chain of Causation (paticcasamuppāda). As he masters this, the earth trembles and, with the dawn, comes Enlightenment. He is now the supreme Buddha, and he breaks forth into a paean of joy (udāna).

There is great doubt as to which were these Udāna verses. The Nidānakathā and the Commentaries generally quote two verses (153, 154) included in the Dhammapada collection (anekajāti samsāram etc.). The Vinaya (i.2) quotes three different verses (as does also DhsA.17), and says that one verse was repeated at the end of each watch, all the watches being occupied with meditation on the paticcasamuppāda. Mtu. (ii.286) gives a completely different Udāna, and in another place (ii.416) mentions a different verse as the first Udāna. The Tibetan Vinaya is, again, quite different (Rockhill, p.33). For a discussion see Thomas, op. cit., 75ff.

For the first week the Buddha remains under the Bodhi-tree, meditating on the Paticcasamuppāda; the second week he spends at the Ajapālanigrodha, where the “Huhuhka” Brahmin accosts him (Mara now comes again and asks the Buddha to die at once; D.ii.112) and where Mara’s daughters, Tanhā, Aratī and Rāgā, appear before the Buddha and make a last attempt to shake his resolution (J.i.78; S. i.124; Lal.490 (378)); the third week he spends under the hood of the nāga-king Mucalinda (Vin.i.3); the fourth week is spent in meditation under the Rājāyatana tree*; at the end of this period takes place the conversion of Tapussa and Bhallika. They take refuge in the Buddha and the Dhamma, though the Buddha does not give them any instruction.

*This is the Vinaya account

(Vin.i.1ff); but the Jātaka (i.77ff, extends this period to seven weeks, the

additional weeks being inserted between the first and second. The Buddha

spends one week each at the Animisa-cetiya, the Ratanacankama and the

Ratanaghara, and this last is where he thinks out the Abhidhamma Pitaka.

Doubts now assail the Buddha as to whether he shall proclaim to the world his doctrine, so recondite, so hard to understand. The Brahma Sahampati (according to J. i.81, with the gods of the thousand worlds, including Sakka, Suyāma, Santusita, Sunimmita, Vasavatti, etc.) appears before him and assures him there are many prepared to listen to him and to profit by his teaching, and so entreats him to teach the Dhamma. The Buddha accedes to his request and, after consideration, decides to teach the Dhamma first to the Pañcavaggiyas at Isipatana. On the way to Benares he meets the ājīvaka Upaka and tells him that he (the Buddha) is Jina.

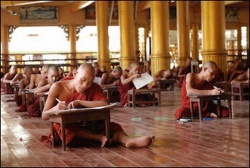

On his arrival at Isipatana the Pañcavaggiyas are, at first, reluctant to acknowledge his claim to be the Tathāgata, but they let themselves be won over and, on the full-moon day of Āsālha, the Buddha preaches to them the sermon which came to be known as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. (Vin.i.4ff; M.i.118ff; cp. D.ii.36ff. Regarding the claim of this sutta to be the Buddha’s first sermon, see Thomas, op. cit., p.86; see also Pañcavaggiyā). At the end of the sermon Kondañña becomes a sotāpanna and they all become monks.

This sermon is followed five days later by the Anattalakkhana Sutta, at the conclusion of which all five become arahants. The following day the Buddha meets Yasa, whom he converts. Yasa’s father, who comes seeking him, is the first to take the threefold formula of Refuge.

Yasa becomes an arahant and is ordained.

The Buddha accepts a meal at his house, and Yasa’s mother and one of his former wives are the first two lay-women to become the Buddha’s disciples. Then four friends of Yasa and, afterwards, fifty more, enter the Order and become arahants. There are now sixty arahants besides the Buddha, and they are sent in different directions to preach the Dhamma. They return with many candidates for admission to the Order, and the Buddha, who up till now had ordained men with the “ehi bhikkhu” formula, now allows the monks themselves to perform the ceremony of ordination (Vin.i.15ff; J. i.81f).

After spending the rainy season at Benares (about this time Māra twice tries to tempt the Buddha, once after he had sent the disciples out to preach and once after the Retreat, S. i.105, 111; Vin.i.21, 22), the Buddha returns to Senānigāma in Uruvela, on the way converting and ordaining the thirty Bhaddavaggiyā. At Uruvela, after a long and protracted exercise of magical powers, consisting in all of three thousand five hundred miracles, the Buddha wins over the three Kassapa brothers, the Tebhātika Jatilā, with their thousand followers, and ordains them. They become arahants after listening to the Ādittapariyāya Sutta preached at Gayāsīsa; with these followers he visits Rājagaha, where King Seniya Bimbisāra comes to see him at the Latthivanuyyāna. The following day the Buddha and the monks visit the palace, preceded by Sakka disguised as a youth and singing the praises of the Buddha. After the meal, the king gifts Veluvana to the Buddha and the Order. The Buddha stays for two months at Rājagaha (BuA.4), and it is during this time that Sāriputta and Moggallāna join the Order, through the instrumentality of Assaji (Vin.i.23ff). It was probably during this year, at the beginning of the rainy season, that the Buddha visited Vesāli at the request of the Licchavis, conveyed through Mahāli. The city was suffering from pestilence and famine. The Buddha went, preached the Ratana Sutta and dispelled all dangers (DhA.iii.436ff).

The number of converts now rapidly increases and the people of Magadha, alarmed by the prospect of childlessness, widow-hood, etc., blame the Buddha and his monks. The Buddha, however, refutes their charges (Vin.i.42f).

The account of the first twenty years of

the Buddha’s ministry is summarised from various sources, chiefly from Thomas’s admirable account in his Life and Legend of the Buddha (pp.97ff). The necessary references are to be found under the names mentioned.

On the full-moon day of Phagguna (February-March) the Buddha, accompanied by twenty thousand monks, sets out for Kapilavatthu at the express request of his father, conveyed through Kāludāyī. (This visit is not mentioned in the Canon; but see Thag.527-36; AA.i.107, 167; J.i.87; DhA.i.96f; ThagA.i.997ff).

By slow stages he arrives at the city, where he stays at the Nigrodhārāma, and, in order to convince his proud kinsmen of his power, performs the Yamakapātihārjya and then relates the Vessantara Jātaka. The next day, receiving no invitation to a meal, the Buddha begs in the streets of the city; this deeply grieves Suddhodana, but later, learning that it is the custom of all Buddhas, he becomes a sotāpanna and conducts the Buddha and his monks to meal at the palace. There all the women of the palace, excepting only Rāhulamātā, come and do reverence to the Buddha. Mahā Pajāpatī becomes a sotāpanna and Suddhodana a sakadāgāmi. The Buddha visits Rāhulamātā in her own apartments and utters her praises in the Candakinnara Jātaka. The following day the Buddha persuades his half-brother, Nanda, to come to the monastery, where he ordains him and, on the seventh day, he does the same with Rāhula. This is too great a blow for Suddhodana, and at his request the Buddha rules that no person shall be ordained without the consent of his parents. The next day the Buddha preaches to Suddhodana, who becomes an anāgāmī. During the Buddha’s visit to Kapilavatthu, eighty thousand Sākyans join the Order, one from each family. With these he returns to Rājagaha, stopping on the way at Anupiya, where Anuruddha, Bhaddiya, Ananda, Bhagu, Kimbila and Devadatta, together with their barber, Upāli, visit him and seek ordination.

On his return to Rājagaha the Buddha resides in the Sītavana. (J.i.92, the story is also told in the Vinaya ii.154, but no date is indicated). There Sudatta, later known as Anāthapindika, visits him, is converted, and invites him to Sāvatthi. The Buddha accepts the invitation and journeys through Vesāli to Sāvatthi, there to pass the rainy season. (Vin.ii.158; but see BuA.3, where the Buddha is mentioned as having spent the vassa in Rājagaha). Anāthapindika gifts Jetavana, provided with every necessity, for the residence of the Buddha and his monks. Probably to this period belongs the conversion of Migāra, father-in-law of Visākhā, and the construction, by Visākhā, of the Pubbārāma at Sāvatthi. The vassa of the fourth year the Buddha spends at Veluvana, where he converts Uggasena. (DhA.iv.59f). In the fifth year Suddhodana dies, having realised arahant-ship, and the Buddha flies through the air, from the Kūtāgārasālā in Vesāli where he was staying, to preach to his father on his death-bed. According to one account it is at this time that the quarrel breaks out between the Sākyans and the Koliyans regarding the irrigation of the river Rohinī. (AA.i.186; SnA.i.357; ThigA.141; details of the quarrel are given in J. v.412ff). The Buddha persuades them to make peace, and takes up his abode in the Nigrodhārāma. Mahā Pajāpatī Gotamī, with other Sākiyan women, visits him there and asks that women may be allowed to join the Order. Three times the request is made, three times refused, the Buddha then returning to Vesāli. The women cut off their hair, don yellow robes and follow him thither. Ananda intercedes on their behalf and their request is granted. (Vin.ii.253ff; A.iv.274f.; for details see Mahā Pajāpati).

In the sixth year the Buddha again

performs the Yamakapātihāriya, this time at the foot of the Gandamba tree in Sāvatthi. Prior to this, the Buddha had forbidden any display of magic powers, but makes an exception in his own case (DhA.iii.199f.; J. iv.265, etc.).

He spends the vassa at Mankulapabbata.

After the performance of the miracle he follows the custom of all Buddhas and ascends to Tāvatimsa in three strides to preach the Abhidhamma to his mother who is born there as a deva, and there he keeps the seventh vassa. The multitude, gathered at Sāvatthi at the Yamakapātihāriya, refuse to go away until they have seen him. For three months, therefore, Moggallāna expounds to them the Dhamma, while Culla Anāthapindika provides them with food. During the preaching of the Abhidhamma, Sāriputta visits the Buddha daily and learns from him all that has been recited the previous day. At the end of the vassa, the Buddha descends a jewelled staircase and comes to earth at Sankassa, thirty leagues from Sāvatthi. (For details see Devorohana). It was about this time, when the Buddha’s fame was at its height, that the notorious Ciñcā-mānavikā was persuaded by members of some hostile sect to bring a vile accusation against the Buddha. A similar story, told in connection with a paribbājikā named Sundarī, probably refers to a later date.

The eighth year the Buddha spends in the country of the Bhaggas and there, while residing in Bhesakalāvana near Sumsumāragiri, he meets Nakulapitā and his wife, who had been his parents in five hundred former births (A.A.i.217).

The same is told of another old couple in Sāketa. See the Sāketa Jātaka. The Buddha evidently stayed again at Sumsumāragiri many years later. It was during his second visit that Bodhirājakumāra (q.v.) invited him to a meal at his new palace in order that the Buddha might consecrate the building by his presence.

In the ninth year the Buddha is at Kosambī. While on a visit to the Kuru country he is offered in marriage Māgandiyā, the beautiful daughter of the brahmin Māgandiyā. The refusal of the offer, accompanied by insulting remarks about physical beauty, arouses the enmity of Māgandiyā who, thenceforward, cherishes hatred against the Buddha.

Sn., pp.163ff; SnA.ii.542ff; DhA.i.199ff

Thomas (op. cit., 109) assigns the Māgandiyā incident to the ninth year. I am not sure if this is correct, for the Commentaries say the Buddha was then living at Sāvatthi.

In the tenth year there arises among the monks at Kosambī a schism which threatens the very existence of the Order. The Buddha, failing in his attempts to reconcile the disputants, retires in disgust to the Pārileyyaka forest, passing on his way through Bālakalonakāragāma and Pācīnavamsadāya. In the forest he is protected and waited upon by a friendly elephant who has left the herd. The Buddha spends the rainy season there and returns to Sāvatthi. By this time the Kosambī monks have recovered their senses and ask the Buddha’s pardon. This is granted and the dispute settled. (Vin.i.337ff; J. iii.486f; DhA.i.44ff; but see Ud.iv.5; s.v. Pārileyyaka).

In the eleventh year the Buddha resides at the brahmin village of Ekanālā and converts Kasi-Bhāradvāja (Sn., p.12f.; S.i.172f). The twelfth year he spends at Verañjā, keeping the vassa there at the request of the brahmin Verañja. But Verañja forgets his obligations; there is a famine, and five hundred horse-merchants supply the monks with food. Moggallāna’s offer to obtain food by means of magic power is discouraged (Vin.iii.1ff; J. iii.494f; DhA.ii.153). The thirteenth Retreat is kept at Cālikapabbata, where Meghiya is the Buddha’s personal attendant (A.iv.354; Ud.iv.1). The fourteenth year is spent at Sāvatthi, and there Rāhula receives the upasampadā ordination.

In the fifteenth year the Buddha revisits Kapilavatthu, and there his father-in-law, Suppabuddha, in a drunken fit, refuses to let the Buddha pass through the streets. Seven days later he is swallowed up by the earth at the foot of his palace (DhA.iii.44).

The chief event of the sixteenth year, which the Buddha spent at Ālavī, is the conversion of the yakkha Ālavaka. In the seventeenth year the Buddha is back at Sāvatthi, but he visits Ālavī again out of compassion for a poor farmer who becomes a sotāpanna after hearing him preach (DhA.iii.262ff). He spends the rainy season at Rājagaha. In the next year he again comes to Ālavī from Jetavana for the sake of a poor weaver’s daughter. She had heard him preach, three years earlier, on the desirability of meditating upon death. She alone gave heed to his admonition and, when the Buddha knows of her imminent death, he journeys thirty leagues to preach to her and establish her in the sotāpattiphala (DhA.iii.170ff).

The Retreat of this year and also that of the nineteenth are spent at Cālikapabbata. In the twentieth year takes place the miraculous conversion of the robber Angulimāla. He becomes an arahant and dies shortly after. It is in the same year that Ananda is appointed permanent attendant on the Buddha, a position which he holds to the end of the Buddha’s life, twenty-five years later (For details see Ananda). The twentieth Retreat is spent at Rājagaha.

With our present knowledge it is impossible to evolve any kind of chronology for the remaining twenty-five years of the Buddha’s life. The Commentaries state that they were spent at Sāvatthi in the monasteries of Jetavana and Pubbārāma. (E.g., BuA.3; SnA. p.336f, says that when the Buddha was at Sāvatthi, he spent the day at the Migāramātupāsāda in the Pubbārāma, and the night at Jetavana or vice versa).

This, probably, only implies that the Retreats were kept there and that they were made the head quarters of the Buddha. From there, during the dry season, he went every year on tour in various districts. Among the places visited by him during these tours are the following:

Aggālavacetiya, Anotatta, Andhakavinda,

Ambapālivana, Ambalatthikā, Ambasandā, Assapura, Āpana, Icchānangala, Ukkatthā

(Subhagavana), Ukkācelā, Ugganagara, Ujuññā (Kannakatthaka deer-park), Uttara

in Koliya, Uttarakā, Uttarakuru, Uruvelakappa, Ulumpa, Ekanālā, Opasāda,

Kakkarapatta, Kajangalā (Mukheluvana), Kammāssadhamma, Kalandakanivāpa (near

Benares), Kimbilā, Kītāgiri, Kundadhānavana (near Kundakoli), Kesaputta,

Kotigāma, Kosambī (Ghositārāma and Badarikārāma), Khānumata, Khomadussa,

Gosingasālavana, Candalakappa, Campā (Gaggarā), Cātuma, Cetiyagiri in Vesāli,

Jīvakambavana (in Rājagaha), Tapodārāma, Tindukkhānu (paribbājakārāma),

Todeyya, Thullakotthita, Dakkhināgiri, Dandakappa, Devadaha, Desaka in the

Sumbha country, Nagaraka, Nagaravinda, Nādikā (Giñjakāvasatha), Nālandā (Pāvārika

mango-grove), Nālakapāna (Palāsavana), Pankadhā, Pañcasalā, Pātikārāma, Beluva,

the Brahma world, Bhaddavatī, Bhaddiya (Jātiyāvana), Bhaganagara (Anandacetiya),

Maninālakacetiya, Mana-sākata, Mātulā, Mithilā (Makhādeva mango-grove),

Medatalumpa, Moranivāpa, Rammaka’s hermitage, Latthivana, Videha,

Vedhañña-ambavana, Venāgapura, Verañjā, Veludvāra, Vesāli (also various

shrines there, Udenacetiya, Gotamacetiya, Cāpalacetiya, Bahuputta-kacetiya,

Sattambacetiya, Sārandadacetiya), Sakkara, Sajjanela, Salalāgāraka in

Sāvatthi, Sāketa (Añjanavana), Sāmagāma, Sālavatikā, Sālā, Simsapāvana,

Silāvatī, Sītavana, Sūkarakhatalena, Setavyā, Hatthigāma, Halidavassana and

the region of the Himālaya.

There is a more or less continuous account of the last year of the Buddha’s life. This is contained in three suttas: the Mahā Parinibbāna, the Mahā Sudassana and the Janavasabha. These are not separate discourses but are intimately connected with each other. The only event prior to the incidents recounted in these suttas, which can be fixed with any certainty, is the death of the Buddha’s pious patron and supporter, Bimbisāra, which took place eight years before the Buddha’s Parinibbāna (Mhv.ii.32). It was at this time that Devadatta tried to obtain for himself a post of supremacy in the Order, and, failing in this effort, became the open enemy of the Buddha. Devadatta’s desire to deprive the Buddha of the leadership of the Sangha seems to have been conceived by him, according to the Vinaya account (Vin.ii.184), almost immediately after he joined the Order, and the Buddha was warned of this by the devaputta Kakudha. This account lends point to the statement contained especially in the Northern books, that even in their lay life Devadatta had always been Gotama’s rival.

Enlisting the support of Ajātasattu, he

tried in many ways to kill the Buddha. Royal archers were bribed to shoot the Buddha, but they were won over by his personality and confessed their intentions. Then Devadatta hurled a great rock down Gijjhakūta on to the Buddha as he was walking in the shade of the hill; the hurtling rock was stopped by two peaks, but splinters struck the Buddha’s foot and caused blood to flow; he suffered great pain and had to be taken to the Maddakucchi garden, where his injuries were dressed by the physician Jīvaka (S.i.27). The monks wished to provide a guard, but the Buddha reminded them that no man had the power to deprive a Tathāgata of his life.

Devadatta next bribed the royal elephant

keepers to let loose a fierce elephant, Nālāgiri, intoxicated with toddy, on the road along which the Buddha would go, begging for alms. The Buddha was warned of this but disregarded the warning, and when the elephant appeared, Ananda, against the strict orders of the Buddha, threw himself in its path, and only by an exercise of iddhi-power, including the folding up of the earth, could the Buddha come ahead of him. As the elephant approached, the Buddha addressed it, pervading it with his boundless love, until it became quite gentle. (This incident, with great wealth of detail, is related in several places - e.g., in J.v.333ff).

These attempts to encompass the Buddha’s death having failed, Devadatta, with three others, decides to create a schism in the Order and asks the Buddha that five rules should be laid down, whereby the monks would be compelled to lead a far more austere life than hitherto. When this request is refused, Devadatta persuades five hundred recently ordained monks to leave Vesāli with him and take up their residence at Gayāsīsa, where he would set up an organisation similar to that of the Buddha. But, at the Buddha’s request, Sāriputta and Moggallāna visit the renegade monks; Sāriputta preaches to them and they are persuaded to return. When Devadatta discovers this, he vomits hot blood and lies ill for nine months. When his end approaches, he wishes to see the Buddha, but he dies on the way to Jetavana - whither he is being conveyed in a litter - and is born in Avīci.

From Gijjhakūta, near Rājagaha, the

Buddha starts on his last journey. Just before his departure he is visited by Vassākāra, and the talk is of the Vajjians; the Buddha preaches to Vassākāra and the monks on the conditions that lead to prosperity. The Buddha proceeds with a large concourse of monks to Ambalatthikā and thence to Nālandā, where Sāriputta utters his lion-roar (sīhanāda) regarding his faith in the Buddha. The Buddha then goes to Pātaligāma, where he talks to the villagers on the evil consequences of immorality and the advantages of morality. He utters a prophecy regarding the future greatness of Pātaliputta and then, leaving by the Gotamadvāra, he crosses the river Ganges at Gotamatittha. He proceeds to Kotigāma and thence to Ñātika, where he gives to Ananda the formula of the Dhammādāsa, whereby the rebirth of disciples could be ascertained. From Ñātika he goes to Vesāli, staying in the park of the courtesan Ambapāli. The following day he accepts a meal from Ambapāli, refusing a similar offer from the Licchavis; Ambapāli makes a gift of her park to the Buddha and his monks. The Buddha journeys on to Beluva, where he spends the rainy season, his monks remaining in Vesāli. At Beluva he falls dangerously ill but, with great determination, fights against his sickness. He tells Ananda that his mission is finished, that when he is dead the Order must maintain itself, taking the Dhamma alone as its refuge, and he concludes by propounding the four subjects of mindfulness (D.ii.100). The next day he begs in Vesāli and, with Ananda, visits the Cāpāla-cetiya. There he gives to Ananda the opportunity of asking him to live until the end of the kappa, but Ananda fails to take the hint. Soon afterwards Māra visits the Buddha and obtains the assurance that the Buddha’s nibbāna will take place in three months. There is an earthquake, and, in answer to Ananda’s questions, the Buddha explains to him the eight causes of earthquakes. This is followed by lists of the eight assemblies, the eight stages of mastery and the eight stages of release. The Buddha then repeats to Ananda his conversation with Māra, and Ananda now makes his request to the Buddha to prolong his life, but is told that it is now too late; several opportunities he has had, of which he has failed to avail himself. The monks are assembled in Vesāli, in the Service Hall, and the Buddha exhorts them to practise the doctrines he has taught, in order that the religious life may last long. He then announces his impending death.

According to the Commentaries (e.g.,

DA.ii.549), after the rainy season spent at Beluva, the Buddha goes back to Jetavana, where he is visited by Sāriputta, who is preparing for his own Parinibbāna at Nālakagāma. From Jetavana the Buddha went to Rājagaha, where Mahā-Moggallāna died. Thence he proceeded to Ukkācelā, where he spoke in praise of the two chief disciples. From Ukkācelā he proceeded to Vesāli and thence to Bhandagāma. Rāhula, too, predeceased the Buddha (DA.ii.549).

The next day, returning from Vesāli, he

looks round at the city for the last time and goes on to Bhandagāma; there he preaches on the four things the comprehension of which destroys rebirth-noble conduct, earnestness in meditation, wisdom and freedom.

He then passes through the villages of

Hatthigāma, Ambagāma and Jambugama, and stays at Bhoganagara at the Ananda-cetiya. There he addresses the monks on the Four Great Authorities (Mahāpadesā), by reference to which the true doctrine may be determined (Cf. A.ii.167ff). From Bhoganagara the Buddha goes to Pāvā and stays in the mango-grove of Cunda, the smith. Cunda serves him with a meal which includes sūkaramaddava. (There is much dispute concerning this word. See Thomas, op. cit., 149, n.3). The Buddha alone partakes of the sūkaramaddava, the remains being buried. This is the Buddha’s last meal; sharp sickness arises in him, with flow of blood and violent, deadly pains, but the Buddha controls them and sets out for Kusinārā. On the way he has to sit down at the foot of a tree. Ananda fetches him water to drink from the stream Kakutthā, over which five hundred carts had just passed; but, through the power of the Buddha, the water is quite clear. Here the Buddha is visited by Pukkusa, the Mallan, who is converted and presents the Buddha with a pair of gold-coloured robes. The Buddha puts them on and Ananda notices the marvellous brightness and clearness of the Buddha’s body. The Buddha tells him that the body of a Buddha takes on this hue on the night before his Enlightenment and on the night of his passing away, and that he will die that night at Kusinārā. He goes to the Kākutthā, bathes and drinks there and rests in a mango-grove. There he instructs Ananda that steps must be taken to dispel any remorse that Cunda may feel regarding the meal he gave to the Buddha.

From Kakutthā the Buddha crosses the

Hiraññavatī to the Upavattana sāla-grove in Kusinārā. There Ananda prepares for him a bed with the head to the north. All the trees break forth into blossom and flowers cover the body of the Buddha. Divine mandārava-flowers and sandalwood powder fall from the sky, and divine music and singing sound through the air. But the Buddha says that the greater honour to him would be to follow his teachings.

The gods of the ten thousand world systems assemble to pay their last homage to the Buddha, and Upavāna, who stands fanning him, is asked to move away as he obstructs their view.

Ananda asks for instruction on several

points, including how the funeral rites should be performed; he then goes out and abandons himself to a fit of weeping; the Buddha sends for him, consoles him and speaks his praises. Ananda tries to persuade the Buddha not to die in a mud-and-wattle village, such as is Kusinārā, but the Buddha tells him how it was once the mighty Kusāvatī, capital of Mahāsudassana.

The Mallas of Kusināra are informed that

the Buddha will pass away in the third watch of the night, and they come with their families to pay their respects. The ascetic Subhadda comes to see the Buddha and is refused admission by Ananda, but the Buddha, overhearing, calls him in and converts him. Several minor rules of discipline are delivered, including the order for the excommunication of Channa. The Buddha finally asks the assembled monks to speak out any doubts they may have. All are silent and Ananda expresses his astonishment, but the Buddha tells him it is natural that the monks should have no doubts. Then, addressing the monks for the last time, he admonishes them in these words: “Decay is inherent in all component things; work out your salvation with diligence.” These were the Buddha’s last words. Passing backwards and forwards through various stages of trance, he attains Parinibbāna. There is a great earthquake and terrifying thunder, and the Brahmā Sahampati, Sakka king of the gods, Anuruddha and Ananda utter stanzas, each proclaiming the feeling uppermost in his mind. It is the full-moon day of the month of Visākha and the Buddha is in his eightieth year.

The next day Ananda informs the Mallas

of Kusinārā of the Buddha’s death, and for seven days they hold a great celebration. On the seventh day, following Ananda’s instructions, they prepare the body for cremation, taking it in procession by the eastern gate to the Makutabandhana shrine, thus altering their proposed route, in order to satisfy the wishes of the gods, as communicated to them by Anuruddha. The whole town is covered knee-deep with mandārava-flowers, which fall from the sky. When, however, four of the chief Mallas try to light the pyre, their attempt is unsuccessful and they must wait until Mahā Kassapa, coming with a company of five hundred monks, has saluted it. The Commentaries (e.g., DA.ii.603) add that Mahā Kassapa greatly desired that the Buddha’s feet should rest on his head when he worshipped the pyre. The wish was granted: the feet appeared through the pyre, and when Kassapa had worshipped them, the pyre closed together. The pyre burns completely away, leaving no cinders nor soot. Streams of water fall from the sky to extinguish it and the Mallas pour on it scented water. They then place a fence of spears around it and continue their celebrations for seven days. At the end of that period there appear several claimants for the Buddha’s relics: Ajātasattu, the Licchavis of Vesāli, the Sākiyans of Kapilavatthu, the Bulis of Allakappa, the Koliyas of Rāmagāma, a brahmin of Vethadīpa and the Mallas of Pāvā. But the Mallas of Kusinārā refusing to share the relics with the others, there is danger of war. Then the brahmin Dona counsels concord and divides the relics into eight equal parts for the eight claimants. Dona takes for himself the measuring vessel and the Moriyas of Pipphalivana, who arrive late, carry off the ashes. Thūpas were built over these remains and feasts held in honour of the Buddha.

S

The complete passing away.

The concluding passage of the

Mahā-Parinibbāna Sutta (D.ii.167) states that the Buddha’s relics were eight measures, seven of which were honoured in Jambudīpa and the remaining one in the Nāga realm in Rāmagāma. One tooth was in heaven, one in Gandhāra, a third in Kālinga (later taken to Ceylon), and a fourth in the Nāga world. Ajātasattu’s share was deposited in a thūpa and forgotten. It was later discovered by Asoka (with the help of Sakka) and distributed among his eighty-four thousand monasteries. Asoka also recorded the finding of all the other relics except those deposited in Rāmagāma. These were later deposited in the Mahācetiya at Anurādhapura (Mhv.Xxxi.17ff). Other relics are also mentioned, such as the Buddha’s collar-bone, his alms bowl, etc. (Mhv.Xvii.9ff; Mhv.i.37, etc.).

It is said (E.g., DA.iii.899) that just

before the Buddha’s Sāsana disappears completely from the world, all the relics will gather together at the Mahācetiya, and travelling from there to Nāgadīpa and the Ratanacetiya, assemble at the Mahābodhi, together with the relics from other parts. There they will reform the Buddha’s golden hued body, emitting the six-coloured aura. The body will then catch fire and completely disappear, amid the lamentations of the ten thousand world-systems.

The Ceylon Chronicles (Mhv.i.12ff;

Dpv.i.45ff; ii.1ff etc.) record that the Buddha visited the Island on three separate occasions.

(The Burmese claim that the Buddha

visited their land and went to the Lohitacandana Vihāra, presented by the

brothers Mahāpunna and Cūlapunna of Vānijagāma (Ind. Antiq.xxii., and

Sās.36f.).

The first was while he was dwelling at

Uruvelā, awaiting the moment for the conversion of the Tebhātika Jatilas, in the ninth month after the Enlightenment, on the full-moon day of Phussa (Dec. Jan.). He came to the Mahānāga garden, and stood in the air over an assembly of yakkhas then being held. He struck terror into their hearts and, at his suggestion, they left Ceylon and went in a body to Giridīpa, hard by. The Buddha gave a handful of his hair to the deva Mahāsumana of the Sumanakūta mountain, who built a thūpa which was later enlarged into the Mahiyangana Thūpa. The Buddha again visited Ceylon in the fifth year, on the new-moon day of Citta (March-April), to check an imminent battle between two Nāga chiefs in Nāgadīpa; the combatants were Mahodara and Cūlodara, uncle and nephew, and the object of the quarrel was a gem-set throne. The Buddha appeared before them, accompanied by the deva Samiddhi-Sumana, carrying a Rājayatana tree from Jetavana, settled their quarrel and received, as a gift, the throne, the cause of the trouble. He left behind him both the throne and the Rājayatana tree for the worship of the Nāgās and accepted an invitation from the Nāga king, Maniakkhika of Kalyāni, to pay another visit to Ceylon. Three years later Maniakkhika repeated the invitation and the Buddha came to Kalyāni with five hundred monks, on the second day of Vesākha. Having preached to the Nāgas, he went to Sumanakūta, on the summit of which mountain he left the imprint of his foot (Legend has it that other footprints were left by the Buddha, on the bank of the river Nammadā, on the Saccabaddha mountain and in Yonakapura). He then stayed at Dīghavāpī and from there visited Mahāmeghavana, where he consecrated various spots by virtue of his presence, and proceeded to the site of the later Silācetiya. From there he returned to Jetavana.

Very little information as to the

personality of the Buddha is available. We are told that he was golden-hued (E.g., Sp.iii.689), that his voice had the eight qualities of the Brahmassāra (E.g., D.ii.211; M.ii.166f. It is said that while an ordinary person spoke one word, Ananda could speak eight; but the Buddha could speak sixteen to the eight of Ananda, MA.i.283) - fluency, intelligibility, sweetness, audibility, continuity, distinctness, depth and resonance - that he had a fascinating personality - he was described by his opponents as seductive (E.g., M.i.269, 275) - that he was handsome, perfect alike in complexion and stature and noble of presence (E.g., M.ii.167). He had a unique reputation as a teacher and trainer of the human heart. He was endowed with the thirty-two marks of the Mahāpurisa. (For details of these, see Buddha). There is a legend that Mahā Kassapa, though slightly shorter, resembled the Buddha in appearance.

Attempts made, however, to measure the

Buddha always failed; two such attempts are generally mentioned - one by a brahmin of Rājagaha and the other by Rāhu, chief of the Asuras (DA.i.284f). The Buddha had the physical strength of many millions of elephants (e.g., VibhA.397), but his strength quickly ebbed away after his last meal and he had to stop at twenty-five places while travelling three gāvutas from Pāvā to Kusināra (DA.ii.573).

Mention is often made of the Buddha’s

love of quiet and peace, and even the heretics respected his wishes in this matter, silencing their discussions at his approach (E.g., D.i.178f; iii.39; even his disciples had a similar reputation, e.g., D.iii.37). Examples are given of the Buddha refusing to allow noisy monks to live near him. (E.g., M.i.456; see also M.ii.122, where a monk was jogged by his neighbour because he coughed when the Buddha was speaking). He loved solitude and often spent long periods away from the haunts of men, allowing only one monk to bring him his meals. E.g., S. v.12, 320; but this very love of solitude was sometimes brought against him. By intercourse with whom does he attain to lucidity in wisdom? they asked. His insight, they said, was ruined by his habit of seclusion (D.iii.38).

According to one account (A.i.181), it

was his practice to spend part of the day in seclusion, but he was always ready to see anyone who urgently desired his spiritual counsel (E.g., A.iv.438).

In the Mahā Govinda Sutta (D.ii.222f )

Sakka is represented as having uttered “eight true praises” of the Buddha. Perhaps the most predominant characteristics of the Buddha were his boundless love and his eagerness to help all who sought him. His fondness for children is seen in such stories as those of the two Sopākas, of Kumāra-Kassapa, of Cūla Panthaka and Dabba-Mallaputta and also of the novices Pandita and Sukha. His kindness to animals appears, for instance, in the introductory story of the Maccha Jātaka and his interference on behalf of Udena’s aged elephant, Bhaddavatikā (q.v.). The Buddha was extremely devoted to his disciples and encouraged them in every way in their difficult life. The Theragāthā and the Therīgāthā are full of stories indicating that he watched, with great care, the spiritual growth and development of his disciples, understood their problems and was ready with timely interference to help them to win their aims. Such incidents as those mentioned in the Bhaddāli Sutta (M.i.445), the introduction to the Tittha Jātaka and the Kañcakkhandha Jātaka, seem to indicate that he took a personal and abiding interest in all who came under him. It was his unvarying custom to greet with a smile all those who visited him, inquiring after their welfare and thus putting them at their ease (Vin.i.313). When anyone sought permission to question him, he made no conditions as to the topic of discussion. This is called sabbaññupavārana. E.g., M.i.230. When the Buddha himself asked a question of any of his interrogators, they could not remain silent, but were bound to answer; a yakkha called Vajirapāni was always present to frighten those who did not wish to do so (e.g., M.i.231).

The Buddha was not over-anxious to get

converts, and when his visitors declared themselves his followers he would urge them to take time to consider the matter - e.g., in the case of Acela Kassapa and Upāligahapati.

When he was staying in a monastery, he

paid daily visits to the sick ward to talk to the inmates and to comfort them (See, e.g., Kutāgārasālā). The charming story of Pūtigata-Tissa shows that he sometimes attended on the sick himself, thus setting an example to his followers. In return for his devotion, his disciples adored him, but even among those who immediately surrounded him there were a few who refused to obey him implicitly - e.g., Lāludāyī, the companions of Assaji and Punabbasuka, the Chabbaggiyas, the Sattarasavaggiyas and others, not to mention Devadatta and his associates.

The Buddha seems to have shown a special

regard for Sāriputta, Ananda and Mahā Kassapa among the monks, and for Anāthapindika, Mallikā, Visakhā, Bimbisāra and Pasenadi among the laity. He seems to have been secretly amused by the very human qualities of Pasenadi and by his failure to appreciate the real superiority of Mallikā, his wife.

The Buddha always declared that he was

among the happy ones of this earth, that he was far happier, for instance, than Bimbisāra (E.g., M.i.94), and he remained unmoved by opposition or abuse. E.g., in the case of the organised conspiracy of Māgandiyā (DhA.iv.1f.).

The Milindapañha (p.134) mentions

several illnesses of the Buddha: the injury to his foot has already been referred to; once when the humours of his body were disturbed Jīvaka administered a purge (Vin.i.279); on another occasion he suffered from some stomach trouble which was cured by hot water, or, according to some, by hot gruel (Vin.i.210f.; Thag.185). The Dhammapada Commentary (DhA.iv.232; ThagA.i.311f) mentions another disorder of the humours cured by hot water obtained from the brahmin Devahita, through Upavāna. The Commentaries mention that he suffered, in his old age, from constant backache, owing to the severe austerities practised by him during the six years preceding his Enlightenment, and the unsuitable meals taken during that period were responsible for a dyspepsia which persisted throughout the rest of his life (SA.i.200), culminating in his last serious illness of dysentery. MA.i.465; DA.iii.974; see also D.iii.209, when he was preaching to the Mallas of Pāvā.

The Apadāna (Ap.i.299f) contains a set

of verses called Pubbakammapiloti; these verses mention certain acts done by the Buddha in the past, which resulted in his having to suffer in various ways in his last birth. He was once a drunkard named Munāli and he abused the Pacceka Buddha Surabhi. On another occasion he was a learned brahmin, teacher of five hundred pupils. One day, seeing the Pacceka Buddha Isigana, he spoke ill of him to his pupils, calling him “sensualist.” The result of this act was the calumny against him by Sundarikā in this life.

In another life he reviled a disciple of

a Buddha, named Nanda; for this he suffered in hell for twelve thousand years and, in his last life, was disgraced by Ciñcā. Once, greedy for wealth, he killed his step-brothers, hurling them down a precipice; as a result, Devadatta attempted to kill him by hurling down a rock. Once, as a boy, while playing on the highway, he saw a Pacceka Buddha and threw a stone at him, and as a result, was shot at by Devadatta’s hired archers. In another life he was a mahout, and seeing a Pacceka Buddha on the road, drove his elephant against him; hence the attack by Nālāgiri. Once, as a king, he sentenced seventy persons to death, the reward for which he reaped when a splinter pierced his foot. Because once, as a fisherman’s son, he took delight in watching fish being caught, he suffered from a grievous headache when Vidūdabha slaughtered the Sākiyans. In the time of Phussa Buddha he asked the monks to eat barley instead of rice and, as a result, had to eat barley for three months at Verañja. (According to the Dhammapada Commentary [iii.257], the Buddha actually had to starve one day at Pañcasālā, because none of the inhabitants were willing to give him alms.) Because he once killed a wrestler, he suffered from cramp in the back. Once, when a physician, he caused discomfort to a merchant by purging him, hence his last illness of dysentery. As Jotipāla, he spoke disparagingly of the Enlightenment of Kassapa Buddha, and in consequence had to spend six years following various paths before becoming the Buddha. He was one of the most short-lived Buddhas, but because of those six years his Sāsana will last longer (Sp.i.190f).

The Buddha was generally addressed by

his own disciples as Bhagavā. He spoke of himself as Tathāgata, while non-Buddhists referred to him as Gotama or Mahāsamana. Other names used are Mahāmuni, Sākyamuni, Jina, Sakka (e.g., Sn.vs.345) and Brahma (Sn.vs.91; SnA.ii.418), also Yakkha (q.v.).

The Anguttara Nikāya (A.i.23ff) gives a

list of the Buddha’s most eminent disciples, both among members of the Order and among the laity. Each one in the list is mentioned as having possessed pre-eminence in some particular respect.

Among those who visited the Buddha for

discussion or had interviews with him or received instruction and guidance direct from him, the following may be included in addition to those already mentioned (this list does not pretend to be complete; some of the names have already been mentioned in this monograph in various connections):

Ankura, Aggidatta, Acela-Kassapa,

Ajātasattu, Ajita the Paribbājaka, Ajita the Licchavi general, Attadattha,

Anitthigandhakumāra, Anurāddha, Anuruddha, Annabhāra, Abhaya-rājakumāra,

Abhayā, Abhiñjaka, Abhibhūta, Abhirūpa-Nandā, Ambattha, the monk Arittha,

Ariya the fisherman, Asama, Asibandhaputta, Assaji, Assalāyana, Ākotaka,

Āmagandha, the yakkhas Ālavaka and Indaka, Ugga of Vesāli, Ugga the minister,

Uggata-Sarīra, Uggaha, Ujjaya, Unnābha, Uttara-devaputta, Uttara the Nāga king, Uttara, pupil of Pārasariya, Uttiya, Udaya and Udāyi the brahmins,

Uttara, pupil of Brahmāyu, Uttarā, daughter of Punna, Uttarā the aged nun,

Upavāna, Upasālha, Upasena, Upāligahapati, Ubbirī, Eraka, Esakārī, Kakudha,

Kandaraka, Kapila the fisherman, Kappa, Kappatakura, Kalārakkhattiya, Kassapa

the deva, Kāna, Kānamātā, Kātiyāna, Kāpathika, Kāmada, Kāranapāli, the Kālāmas,

Kāligodhā, Kimbila, Kisāgotami, Kukkutamitta the hunter, Kundadhāna, Kundaliya,

Kulla, Kūtadanta, Keniya the Jatila, Kevaddha, Kesi the horse trainer,

Kokanadā, the two daughters of Pajjuna, Kokālika, Khadiravaniya-Revata, Khānu-Kondañña,

Khema the deva, Khemā, Ganaka-Moggallāna, Gavampati, Guttā, Gotama Thera,

Cankī, Candana, Candābha, Candimā (Candimasa), Citta-Hatthasārīputta, Cunda,

Cunda-Samanuddesa, Cundī, Culla-Dhanuggaha, Culla-Subhaddhā, Chattapānī,

Janapada-Kalyāni-Nandā, Janavasabha, Jantu, Jambuka, Jambukhādaka, Jānussoni,

Jāliya, Jīvaka-Komārabhacca, Jenta, Jotikagahapati, Tāyana, Tālaputa, Tikanna,

Timbaruka, Tissa, cousin of the Buddha, Tissa, friend of Metteyya, Tissa of

Roruva, Tudu-brahmā, Thulla-Tissa, Dandapanī, Dāmalī, Dāsaka, Dīgha the deva,

Dīghajānu, Dīghata-passī, Dīghanakha, Dīghalatthi, Dīghāvu, Dummukha, Dona,

Dhammadinna, Dhammārāma, the Dhammika-upāsaka, Dhammika the brahmin, Nanda

Thera, Nanda the herdsman, Nandana, Nandiya-paribbājaka, Nandiya the Sākiyan,

Nandivisāla, Nāgita, Nālakatāpasa, Nālijangha, Nigamavāsi-Tissa, Nigrodha,

Ninka, Nīta, Nhātakamunī, Paccanīkasāta, Pañcasikha, Pañcālacanda, Patācārā,

Pasenadi, king of Kosala, Pahārāda the asura, Pātaliya, Pārāpariya,

Pingala-Kaccha, Pingiyānī, Pilinda-Vaccha, Pilotika, Punna, Punna-Koliyaputta,

Punna-Mantānīputta, Punnā, Punniya, Pessa the elephant trainer, Pokkharasāti,

Potthapāda, Pothila, Potaliya, Phagguna, Baka-brahmā, Bahuputtikā, Bāvarī and

his sixteen disciples, Bāhiya-Dārucīriya, Bāhuna, Bilālapādaka, Belatthakāni,

Bojjhā, Brahmāyu, Bhagu, Bhaggava, Bhadda, Bhaddā-Kundakakesī, Bhaddāli,

Bhaddiya the Licchavi, several Bhāra-dvājas (Akkosaka*, Aggika*, Asurinda*,

Ahimsaka*, Kāsi*, Jatā*, Navakammika*, Bilangika*, Suddhika*, Sundarika*),

Bhāradvāja, husband of Dhanañjāni, Bhāradvāja, friend of Vāsettha, Bhuñjati,

Bhumiya, Bhesika the barber, Macchari-Kosiya, Manibhadda, Mandissa, Mahā-kappina,

Mahā-Kassapa, Mahā-kotthita, Mahā-Cunda, Mahā-dhana, Mahā-nāma,

Mahā-Moggallāna, Mahāli (Otthaddha), the two Māgandiyas - one the brahmin and

one the paribbājaka, Māgha, Mānava-Gāmiya, Mānatthaddha, Mātuposaka,

Mālunkyaputta, Miga-jāla, Migasira, Mendaka of Bhaddiya, Moliya-Phagguna,

Moliya-Sīvaka, Yasoja, Ratthapāla, Rādha, Rāhula, Rāsiya, Rūpānandā, Roja the

Malla, Rohinī, Rohitassa, Lakuntaka-Bhaddiya, the goddess Lājā, Lomasakangiya,

Lohicca, Vakkali, Vangisa, Vajjiyamāhita, Vaddha the Licchavi, Vaddhamāna,

Vappa, Varadhara, Vassakāra, Vārana, Vāsettha-upāsaka, Vāsettha, friend of

Bhāradvāja, Visākha Pañcalaputta, Visākhā, Vīrā, Vekhanasa, Vendu, Vatambari,

Sakuludāyi, Sakka, Sankicca, the two Sangāravas, Sangharakkhita (Bhāgineyya°),

Saccaka, Sajjha, Satullapa-devas, Sanankumāra, Santati, Sandha, Sandhāna,

Samiddhi, Sarabha, Sarabhanga, Sātāgira, Sātāli, Sāti, Sānu, Sikhā-Moggallāna,

Sigāla, Sirimā, Siva, Sīvali, Sīha the general, Sukhā, Suciloma, Sujātā,

daughter-in-law of Anāthapindika, Sudatta, Sunakkhatta, Sunīta,

Sundara-Samudda, Sundarī-Nandā, the leper Suppabuddha, Suppa-vāsā, Subha

Todeyyaputta, the two nuns named Subhā, Subhūti, the novice Sumana, Sumanā,

sister of Pasenadi, Subrahmā, Surādha, Suriya, Susima, Seniya, Seri, Sela,

Sona-Kutikanna, Sona-Kolivisa, Sonadanda, Sonā, the two Sopākas, Hatthaka

Ālavaka, Hatthaka-devaputta and Hemavata.

1. Buddha

A generic name, an appellative - but not a proper name - given to one who has attained Enlightenment (na mātarā katam, na pitarā katam – vimokkhantikam etam buddhānam bhagavantānam bodhiyā mūle … paññatti, MNid.458; Ps.i.174) a man superior to all other beings, human and divine, by his knowledge of the Truth (Dhamma).

The texts mention two kinds of Buddha: viz.,

Pacceka Buddhas - i.e., Buddhas who

also attain to complete Enlightenment but do not preach the way of deliverance

to the world; and

Sammāsambuddhas, who are

omniscient and are teachers of Nibbāna

(Satthāro).

The Commentaries, however (e.g., SA.i.20; AA.i.65) make mention of four classes of Buddha:

Sabaññu-Buddhā

Pacceka Buddhā

Catusacca Buddhā

Suta Buddhā

All arahants (khīnāsavā) are called Catusacca Buddhā and all learned men Bahussuta Buddhā. A Pacceka Buddha practises the ten perfections (pāramitā) for two asankheyyas and one hundred thousand kappas, a Sabbañu Buddha practises it for one hundred thousand kappas and four or eight or sixteen asankheyyas, as the case may be (see below).

Seven Sabbaññu Buddhas are mentioned in the earlier books; these are

Vīpassī

Sikhī

Vessabhū

Kakusandha

Konāgamana

Kassapa

Gotama

E.g., D.ii.5f.; S. ii.5f.; cp. Thag.491; J. ii.147; they are also mentioned at Vin.ii.110, in an old formula against snake bites. Beal. (Catena, p. 159) says these are given in the Chinese Pātimokkha. They are also found in the Sayambhū Purāna (Mitra, Skt. Buddhist Lit. of Nepal, p. 249).

This number is increased in the later books. The Buddhavamsa contains detailed particulars of twenty five Buddhas, including the last, Gotama, the first twenty four being those who prophesied Gotama’s appearance in the world. They are the predecessors of Vipassī, etc., and are the following:

Dīpankara, Kondañña, Mangala, Sumana, Revata, Sobhita, Anomadassī, Paduma,

Nārada, Padumuttara, Sumedha, Sujāta, Piyadassī, Atthadassī, Dhammadassī,

Siddhattha, Tissa and Phussa.

The same poem, in its twenty seventh chapter, mentions three other Buddhas - Tanhankara, Medhankara and Saranankara - who appeared in the world before Dīpankara.

The Lalitavistara has a list of fifty four Buddhas and the Mahāvastu of more than a hundred. The Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta (D.iii.75ff ) gives particulars of

Metteyya Buddha who will be born in the world during the present kappa. The Anāgatavamsa gives a detailed account of

him. Some MSS. of that poem (J.P.T.S. 1886, p. 37) mention the names of ten future Buddhas, all of whom met Gotama who prophesied about them. These are Metteyya, Uttama, Rāma, Pasenadi Kosala, Abhibhū, Dīghasonī, Sankacca, Subha, Todeyya, Nālāgiripalaleyya (sic).

The Mahāpadāna Sutta (D.ii.5f ) which

mentions the seven Buddhas gives particulars of each under eleven heads (paricchedā) -

the kappa in which he is born,

his social rank (jāti),

his family (gotta),

length of life at that epoch (āyu),

the tree under which he attains Enlightenment (bodhi),

the names of his two chief disciples (sāvakayuga),

the numbers present at the assemblies of arahants held by him (sāvakasannipāta),

the name of his personal attendant (upatthākabhikkhu),

the names of his father and mother and of his birthplace.

The Commentary (DA.ii.422ff) adds to these other particulars -

the names of his son and his wife before his Renunciation,

the conveyance (yāna) in which he leaves the world,

the monastery in which his Gandhakuti was placed,

the amount of money paid for its purchase,

the site of the monastery, and the name of his chief lay patron.

In the case of Gotama, the further fact is stated that on the day of his birth there appeared also in the world Rāhulamātā, Ananda, Kanthaka,

Nidhikumbhi (Treasure Trove), the Mahābodhi

and Kāludāyī.

Gotama was conceived under the asterism (nakkhatta) of Uttarāsālha, under which asterism he also made his Renunciation (DA.ii425), preached his first sermon and performed the Twin Miracle. Under the asterism of Visākha he was born, attained Enlightenment and died; under that of Māgha he held his first

assembly of arahants and decided to die; under Assayuja he descended from Tāvatimsa.

The Buddhavamsa Commentary says (BuA.2f) that in the Buddhavamsa particulars of each Buddha are given under twenty two heads, the additional heads being the details of the first sermon, the numbers of those attaining realization of truth (abhisamaya) at each assembly, the names of the two chief women disciples, the aura of the Buddha’s body (ramsi), the height of his body, the name of the Bodhisatta (who was to become Gotama Buddha), the prophecy concerning him, his exertions (padhāna) and the details of each Buddha’s death. The Commentary also says that mention must be made of the time each Buddha lived as a householder, the names of the palaces he occupied, the number of his dancing women, the names of his chief wife, and his son, his conveyance, his renunciation, his practice of austerities, his patrons and his monastery.

There are eight particulars in which the Buddhas differ from each other (atthavemattāni). These are length of life in the epoch in which each is born, the height of his body, his social rank (some are born as khattiyas, others as brahmins), the length of his austerities, the aura of his body (thus, in the case of Mangala, his aura spread throughout the ten thousand world systems, while that of Gotama extended only one fathom; - but when he wishes, a Buddha can spread his aura at will, BuA.106); the conveyance in which he makes his renunciation, the tree under which he attains Enlightenment, and the size of the seat (pallanka) under the Bodhi tree.

Only the first five are mentioned in DA.ii.424; also at BuA.105; all eight are given at BuA.246f., which also gives details under each of the eight heads, regarding all the twenty five Buddhas.

In the case of all Buddhas, there are four fixed spots (avijahitatthānāni). These are:

the site of the seat under the Bodhi tree (bodhipallanka),

the Deer Park at Isipatana where the

first sermon is preached,

the spot where the Buddha first steps on the ground at Sankassa on his

descent from Tusita (Tāvatimsa?)

the spots marked by the four posts of the bed in the Buddha’s

Gandhakuti in Jetavana.

The monastery may vary in size; the site of the city in which it stands may also vary, but not the site of the bed. Sometimes it is to the east of the vihāra, sometimes to the north (DA.ii.424; BuA.247).

Thirty facts are mentioned as being true of all Buddhas (samatimsavidhā dhammatā).

In his last life every Bodhisatta is conscious at the moment of his

conception;

in his mother’s womb he remains cross legged with his face turned

outwards;

his mother gives birth to him in a standing posture;

the birth takes place in a forest grove (araññe);

immediately after birth he takes seven steps to the north and roars the

“lion’s roar”;

he makes his renunciation after seeing the four omens and after a son is

born to him;

he has to practise austerities for at least seven days after donning the

yellow robe;

he has a meal of milk rice on the day of his Enlightenment;

he attains to omniscience seated on a carpet of grass;

he practises concentration in breathing;

he defeats Māra’s forces;

he attains to supreme perfection in all knowledge and virtue at the foot

of the Bodhi tree;

Mahā Brahmā requests him to preach the Dhamma;

he preaches his first sermon in the Deer Park at

Isipatana;

he recites the Pātimokkha to the

fourfold assembly on the full moon day of Māgha;

he resides chiefly in Jetavana, he

performs the Twin Miracle in Sāvatthi;

he preaches the Abhidhamma in Tāvatimsa;

he descends from there at the gate of Sankassa;

he constantly lives in the bliss of phalasamāpatti;

he investigates the possibility of converting others during two jhānas;

he lays down the precepts only when occasion arises for them;

he relates Jātakas when suitable occasions occur;

he recites the Buddhavamsa in the assembly

of his kinsmen;

he always greets courteously monks who visit him;

he never leaves the place where he has spent the rainy season without

bidding farewell to his hosts;

each day he has prescribed duties before and after his meal and during the

three watches of the night;

he eats a meal containing flesh (mamsarajabhojana) immediately before his

death;

and just before his death he enters into the twenty four crores and one

hundred thousand samāpattī.

There are also mentioned four dangers from which all Buddhas are immune:

no misfortune can befall the four requisites intended for a Buddha;

no one can encompass his death;

no injury can befall any of his thirty two

Mahāpurisalakkhanā or eighty anubyañjanā;

nothing can obstruct his aura (BuA.248).

A Buddha is born only in this Cakkavāla out

of the ten thousand Cakkavālas which constitute the jātikkhetta (AA.i.251; DA.iii.897). There can appear only one Buddha in the world at a time (D.ii.225; D.iii.114; the reasons for this are given in detail inMil. 236, and quoted in DA.iii.900f). No Buddha can arise until the sāsana of the previous Buddha has completely disappeared from the world. This happens only with the dhātuparinibbāna (see below). When a Bodhisatta takes conception in his mother’s womb in his last life, after leaving Tusita, there is manifested throughout the world a wonderful radiance, and the ten thousand world systems tremble.

Similar earthquakes appear when he is born, when he attains Enlightenment, when he preaches the first sermon, when he decides to die, when he finally does so (D.ii.108f.; cp. DA.iii.897).

The Mahāpādāna Sutta (D.ii.12-15) and

the Acchariya-bbhuta-dhamma Sutta

(M.iii.119-124) contain accounts of other miracles, which attend the conception and birth of a Buddha. Later books (e.g., J. i.) have greatly enlarged these accounts. They describe how the Bodhisatta, having practised the thirty Pāramī, and made the five great gifts (pañcamahāpariccāgā), and thus reached the pinnacle of the threefold cariyā - ñātattha-cariyā, lokattha-cariyā and buddhi-cariyā - gives the seven mahādānā, as in the case of Vessantara, making the earth tremble seven

times, and is born after death in Tusita.

The Bodhisatta, who later became Vipassī Buddha, remained in Tusita during the whole permissible period - fifty seven crores and sixty seven thousand years. But most Bodhisattas leave Tusita before completing the full span of life there. Five signs appear to warn the devaputta that his end is near (see Deva); the gods of the ten thousand worlds gather round him, beseeching him to be born on earth that he may become the Buddha. The Bodhisatta thereupon makes the five investigations (pañcamahāvilokanāni).

Sometimes only one Buddha is born in a

kappa, such a kappa being called Sārakappa; sometimes two, Mandakappa; sometimes three, Varakappa; sometimes four, Sāramandakappa; rarely five, Bhaddakappa (BuA.158f). No Buddha is born in the early period of a kappa, when men live longer than one hundred thousand years and are thus not able to recognize the nature of old age and death, and therefore not able to benefit by his preaching. When the life of man is too short, there is no time for exhortation and men are full of kilesa.

The suitable age for a Buddha is, therefore, when men live not less than one hundred years and not more than ten thousand. The Bodhisatta must first consider the continent and the country of birth. Buddhas are born only in Jambudīpa, and there, too, only in the

Majjhimadesa. He must then consider the

family; Buddhas are born only in brahmin or khattiya families, whichever is more esteemed during that particular age. Then he must think of the mother: she must be wise and virtuous; and her life must be destined to end seven days after the Buddha’s birth.

Having made these decisions, the Bodhisatta goes to Nandanavana in Tusita, and while wandering

about there “falls away” from Tusita and takes conception. He is aware of his death but unaware of his cuti-citta or dying thought. The Commentators seem to have differed as to whether there is awareness of conception. When the Bodhisatta is conceived, his mother has no further wish for indulgence in sexual pleasure. For seven days previously she observes the uposatha vows, but there is no mention of a virgin birth; the birth might be called parthenogenetic (see Mil.123).

On the day of the actual conception, the mother, having bathed in scented water after the celebration of the Asālha festival, and having eaten choice food, takes upon herself the uposatha

vows and retires to the adorned state bedchamber. As she sleeps, she dreams that the Four Regent Gods raise her with

her bed, and, having taken her to the Himālaya, bathe her in Lake Anotatta, robe her in divine clothes, anoint

her with perfumes and deck her with heavenly flowers (according to the Nidānakathā, J. i.50, it is their queens who do these things, re the Bodhisatta assuming the form of an elephant, see Dial.ii.116n). Not far away is a silver mountain and on it a golden mansion. There they lay her with her head to the east. The Bodhisatta, assuming the form of a white elephant, enters her room, and after circling right wise three times round her bed, smites her right side with his trunk and enters her womb. She awakes and tells her husband of her dream. Soothsayers are consulted, and they prophesy the birth of a Cakka-vatti or of a Buddha.

The two Suttas mentioned above speak of the circumstances obtaining during the time spent by the child in his mother’s womb. It is said (DA.ii.437) that the Bodhisatta is born when his mother is in the last third of her middle age. This is in order that the birth may be easy for both mother and child. Various miracles attend the birth of the Bodhisatta. The Commentaries expound, at great length, the accounts of these miracles given in the Suttas. Immediately after birth the Bodhisatta stands firmly on his feet, and having taken seven strides to the north, while a white canopy, is held over his head, looks round and utters in fearless voice the lion’s roar: “Aggo ‘ham asmi lokassa, jettho ‘ham asmi lokassa, settho ‘ham asmi lokassa, ayam antimā jāti, natthi dāni punabbhavo” (D.ii.15).