Philosophy of the Buddha

- ‘I think this book is excellent . . . a philosophical introduction to Buddhism is just what is needed, and I would very much welcome it. It is written by an accomplished moral philosopher, who treats the material in a careful, sensitive and philosophically rigorous manner.’ Jonardon Ganeri, Nottingham University

Philosophy of the Buddha is a philosophical introduction to the teaching of the Buddha. It carefully guides readers through the basic ideas and practices of the Buddha, including kamma (karma), rebirth, the not-self doctrine, the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, ethics, meditation, nonattachment, and Nibbāna (Nirvana).

The book includes an account of the life of the Buddha as well as comparisons of his teaching with practical and theoretical aspects of some Western philosophical outlooks, both ancient and modern. Most distinctively, Philosophy of the Buddha explores how Buddhist enlightenment could enable us to overcome suffering in our lives and reach our full potential for compassion and tranquillity.

This is one of the first books to introduce the philosophy of the Buddha to students of Western philosophy. Christopher Gowans’ style is exceptionally clear and appropriate for anyone looking for a comprehensive introduction to this growing area of interest. Christopher W. Gowans is professor of philosophy at Fordham University, USA. He is editor of Moral Disagreements (Routledge 2000), Moral Dilemmas (1987) and the author of Innocence Lost: An examination of inescapable moral wrongdoing (1994).

PREFACE

My purpose in writing this book is to provide a philosophical introduction to the teaching of the Buddha. It is intended neither as an apology nor as a critique, but as a thoughtful guide. I try to articulate the Buddha’s teaching, explain how it could make sense, raise critical questions about it, and consider what he could say in response – all from the perspective of a philosopher trained in the West. I have the highest respect for the Buddha’s teaching, and I take it seriously by reflectively engaging it. To a large extent, such critical reflection is encouraged by the Buddha himself. My hope is to motivate readers to take the Buddha seriously as well by thinking through his ideas and reaching their own conclusions about their value.

Many philosophers in the analytic tradition and elsewhere may view this as a quixotic enterprise at best. Yet there is now a well-established trend among some philosophers to look beyond the Western world in their research and especially their teaching. I wholeheartedly endorse this. But there are many dangers in this enterprise, and one of them is superficiality. I have endeavored here to focus on something rather specific, the teaching of the Buddha as represented in the Sutta Piṭaka of the Pāli canon, and to engage it in a serious philosophical way. It is still an introduction suitable for undergraduate students of philosophy. But the aim is to understand and reflect on the Buddha’s teaching in a careful and detailed manner.

Aspects of Buddhism have been finding their way into the Western world for a couple of centuries. Increasingly in the last fifty years, a number of philosophers and scholars with a philosophical bent have been thinking in a sustained and insightful way about Buddhism and the possibilities for bringing Buddhist thought into dialogue with Western philosophy. I am greatly appreciative of their efforts and have benefited immensely from their work. A book of this sort does not lend itself to detailed scholarly disputation, but throughout I have learned much from others, both when I have agreed and not agreed with their interpretations and analyses. Many of these persons are referred to in the brief ‘Suggested reading’ section of each chapter. These are meant to guide readers to some pertinent philosophical discussions of the issues as well as to relevant sections of the Sutta Piṭaka (they are by no means exhaustive).

I have also profited a good deal from discussions of the Buddha’s teaching in the Theravāda tradition. Though this book is not about that tradition, encounters with it have been natural insofar as it regards the Sutta Piṭaka of the Pāli canon as among its authoritative texts. Though I do not always accept traditional interpretations, I have always found it helpful to reflect on them. In general, I have tried to stay close to what is actually in the Sutta Piṭaka in contrast to what developed only later in the tradition. The one area where it was necessary to develop an interpretation at some length is the not-self doctrine (see part 2). What I say about it goes beyond but remains consonant with the spirit of the traditional understanding (and hence is contrary to revisions of this).

Sufficient quotations from the texts have been provided to give readers the flavor of the Buddha’s teaching. But my main emphasis has been on explanation and evaluation. I urge readers to consult the original texts for themselves. Whenever possible, I have quoted more recent translations rather than the older ones of the Pali Text Society. The PTS translations are a tremendous resource and are always worth consulting. But their language is now rather out of date, and the newer translations are more available. For these reasons, the more recent translations are more suitable in an introductory guide. Likewise, my references are to the ordinary pagination rather than to the standardized pagination often used: the latter could be confusing to beginning students, while those already conversant with the texts should be able to move to other editions with comparative ease.

I have benefited greatly from comments on an earlier draft of the entire manuscript by Merold Westphal, Craig Condella, and an anonymous reviewer of this press. Dana Miller provided some insightful feedback on the chapters relating to Hellenistic philosophy, and Leo Lefebvre offered some helpful advice on my discussion of Buddhism and religion. A long conversation with Joseph Roccasalvo about Buddhism one afternoon was also of great value. Additionally, I have learned much from my students while teaching earlier versions of the manuscript in my sophomore philosophy classes the past two years.

Most of all, I was helped in a multitude of ways by my wife Coleen while preparing this book. She has read and commented on the entire manuscript, and we have had innumerable stimulating and illuminating conversations about Buddhism during the past several years. Her caring interest and encouragement, her knowledge and insight, her penetrating but respectful skeptical inquiries, and her numerous suggestions have all been of tremendous value. The book is dedicated to her. Without her loving and perceptive heart, I could not have written it. Finally, I am greatly appreciative of a rather different kind of support from my six-year-old daughter Hannah. Her regular energetic forays into my office while writing my book about ‘Mr Buddha’ have constantly reminded me of the life in terms of which these issues are so important.

ABBREVIATIONS

References are to page numbers, preceded by volume number in roman numerals when appropriate. Translations are sometimes altered slightly for the sake of uniformity.

L The Long Discourses of the Buddha, translated by M. Walshe, Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

M The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha, translated by Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi, Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995.

C The Connected Discourses of the Buddha, 2 vols, translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi, Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000.

G The Book of the Gradual Sayings, 5 vols, translated by F.L. Woodward, 1932–1936, Reprint, London: Pali Text Society, 1972–1979.

N Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: An Anthology of Suttas from the Aṅguttara Nikāya, translated by N. Thera and Bhikkhu Bodhi, Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 1999.

U/I The Udāna: Inspired Utterances of the Buddha and The Itivuttaka: The Buddha’s Sayings, translated by J.D. Ireland, Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 1997.

PART 1: THE BUDDHA’S TEACHING AS A PHILOSOPHY

OBSERVING THE STREAM

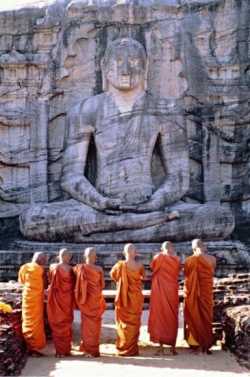

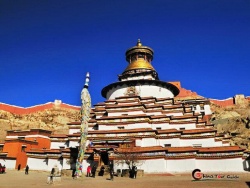

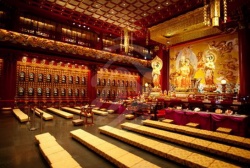

Followers of the Buddha are increasingly visible to people in Western societies. Most Buddhists live in Southeast Asia, China, Korea or Japan, but there are also significant Buddhist populations in countries such as Tibet, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Though accurate measurement is difficult, there are perhaps some 500 million Buddhists in Asia. Western awareness of Buddhists is not entirely new: Christian missionaries and colonial forces entered much of Asia centuries ago. But today, on account of increased ease of communication and transportation, and the general phenomenon of globalization, we in the West now have the opportunity, and sometimes the necessity, of interacting with Buddhists to an extent unprecedented in our past.

In fact, due to immigration and (to a much lesser extent) conversion, many Buddhists now live in Western countries. For example, there are probably at least one to two million Buddhists in the United States of America and significant numbers in European countries such as the United Kingdom and France. This too is not altogether a recent development: there were Chinese Buddhists in California shortly after the Gold Rush of 1849, and Buddhist societies began to spring up in some Western countries in the late nineteenth century. Moreover, closer to our time, books such as Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery (1953) and Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha (1951), along with the writings of D.T. Suzuki and Alan W. Watts, inspired a good deal of popular interest in Buddhism in the period after the Second World War. But in recent years, immigration to the West by Buddhists has increased, and so has interest in Buddhism among persons in the West, such as myself, who were not raised as Buddhists.

An indication of the current interest, and part of its cause, is the prominence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual head and political leader-in-exile. His efforts both on behalf of Tibetan independence from China and in support of inter-religious dialogue between Buddhism and Western religious traditions have attracted much attention. The Dalai Lama’s book The Art of Happiness was on the New York Times ‘best sellers’ list for well over a year. There is also a small movement of ‘Socially Engaged Buddhists’ in some Western countries led partly by Westerners with a serious commitment to Buddhism and partly by persons from traditional Buddhist countries such as Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk now living in France. Buddhism has even entered the arena of popular culture: in sports, advertising, television, movies, and rock music, occasional appearances of Buddhism may be found. Whether it is the golfer Tiger Woods, basketball coach Phil Jackson, actor Richard Gere, pop singer Tina Turner, or Adam Yauch of the rock group the Beastie Boys, it seems we have all heard of a celebrity who has proclaimed allegiance to some form of Buddhism.

In this context of increased awareness and interest, there are many reasons for persons in the West to inquire into Buddhism. One is to learn something about ourselves, to better understand our beliefs and values by comparing them with those of persons in cultures different from our own. A second is to understand something about those cultures, to comprehend how people in societies with Buddhist traditions live their lives. Related to this, a study of Buddhism may help us to interact better with Buddhists and Buddhist countries: it may enable us to approach these encounters in a more informed, responsible, and respectful way. Yet another reason is to see what we can learn from Buddhism, to ascertain whether an understanding of Buddhism might give us grounds for changing our own convictions and practices.

In some measure, this book may facilitate all these concerns, but its primary aim is the last, to reflect on what Buddhism can teach us. Specifically, the purpose is to help those with little or no knowledge of Buddhism to understand and evaluate the teaching of the Buddha from a philosophical perspective. Let us begin by reflecting on some key features of this approach.

1 The nature of this inquiry

We will focus on the teaching of Siddhattha Gotama, the person who became known as the Buddha (the enlightened one).1 There are many ways of studying Buddhism that do not emphasize or go well beyond this teaching. For example, we might investigate the long history of Buddhism, both in its theoretical and practical aspects, in the Asian countries it has influenced. Or we might examine contemporary Buddhist cultures in those countries from the perspective of anthropology, sociology, or religious studies. These are all valuable approaches. But there is also merit in concentrating attention on what the Buddha himself taught. Both the history of Buddhism and its contemporary manifestations are large, complex, and diverse subjects: an introductory survey of them could be informative, but its sheer breadth would not tend to encourage in-depth reflection about what Buddhism might teach us. Though there are various ways of narrowing the field, an obvious approach is to focus on the source common to all Buddhist traditions – the teaching of the Buddha himself.

The Buddha said he taught all human beings a path for achieving enlightenment and well-being. As he approached his death, he laid particular emphasis on the importance of this teaching. To his attendant, Ānanda, he said:

- Ānanda, it may be that you will think: ‘The Teacher’s instruction has ceased, now we have no teacher!’ It should not be seen like this, Ānanda, for what I have taught and explained to you as Dhamma and discipline will, at my passing, be your teacher.

- (L 269–70)

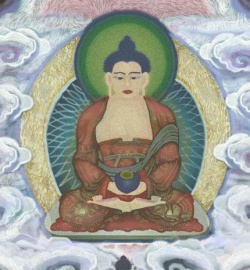

Buddhists everywhere revere as a source of wisdom and guidance the Dhamma of the Buddha, his teaching about the ultimate nature of reality and the way of life that accords with this. (‘Dhamma’ is the Pāli spelling followed here; the more familiar ‘Dharma’ is in Sanskrit.) By examining this teaching, we will be studying the heart of all Buddhist traditions. Of course, these traditions have interpreted and developed the Buddha’s teaching in strikingly different ways. For example, as we move from Sri Lanka to Tibet to Japan, the practice of Buddhism varies significantly. A full understanding of Buddhism would require investigation of these divergences, but they will not be our concern here. We will restrict ourselves to the teaching of the Buddha himself as we now know it.

Our aim is to understand and evaluate the Buddha’s teaching. Some may object that evaluation is not a proper concern of non-Buddhists living in the West, that this is the prerogative of persons in Buddhist cultures. The Buddha himself provided an answer to this contention. He offered his teaching to all human beings, and he invited us all to reflect on what he taught and to learn from it. The intended audience of his message was not restricted to persons of a particular culture or tradition. In fact, the Buddha meant to radically challenge many of the values of his own culture. Moreover, from the northeastern corner of India where he taught some 2,500 years ago, the Buddha’s teaching spread to societies such as China and Japan that were substantially different from his own. We accord the Buddha the highest tribute by accepting his invitation to seriously assess his teaching, not by flatly refusing to do so on the ground that it is the exclusive possession of another culture. By seeking to learn from the Buddha, we are not trying to tell others what they should believe: we are trying to ascertain what we should believe.

Finally, we will endeavor to grasp and appraise the Buddha’s teaching from a philosophical point of view. That is, we will focus mainly on the philosophical aspects of the teaching, and we will seek to render these intelligible and to consider their worth by reflecting on them as a philosopher would. We will bring some characteristic perspectives, concerns, and habits of mind of philosophy to this teaching in order to illuminate it and examine what may be learned from it. Though there are several worthwhile avenues by which persons in the West might engage the teaching of the Buddha, philosophy is a natural one. Philosophy has played a central role in Western traditions, and there is much in the Buddha’s teaching that is philosophical in nature – for example, his ideas concerning the self, impermanence, and dependent origination. Moreover, his teaching gave rise to much explicit philosophical reflection in Asian cultures. Nonetheless, some may object that Western philosophical orientations are not suitable to comprehending and assessing the Buddha’s teaching. The appropriateness and value of this approach will be explained at some length in chapters 4 and 5, but several preliminary points may be made here.

One form of the objection is the claim that, above all else, the Buddha taught a practice – an ensemble of dispositions, skills, and activities aimed at achieving ultimate well-being – and it is a distortion of his teaching to distill a theory from this practice and then consider the theory alone. Indeed, this would be a mistake. However, the practice taught by the Buddha does have theoretical dimensions, and there is much to be learned by focusing on these, so long as we do not lose sight of their practical context. A tradition developed early on in Buddhism that emphasized its theoretical elements (the Abhidhamma literature), and there is at least one important branch of Western philosophy (the Hellenistic tradition) that stressed its practical significance. This suggests that lines of communication are available by which persons with a Western philosophical perspective might constructively encounter the teaching of the Buddha.

Another form of this objection is the assertion that the Buddha taught a religion and not a philosophy. The first part of this contention presumably is correct, depending on what we mean by the term ‘religion’. The Buddha did not believe in God and hence did not regard his teaching as divine revelation. But in many respects it is appropriate to consider his teaching a religion – for example, it centrally involves a notion of transcendence. However, that the Buddha’s teaching is a religion in these respects does not entail that it is not, or does not include, a philosophy. The terms ‘Christian philosophy’ or ‘Jewish philosophy’ are not ordinarily considered oxymorons, and the existence of God is an important part of the theories of many canonical figures in Western philosophy. Though the purpose of our inquiry is not primarily comparative, we will see that there are numerous points of contact between the teaching of the Buddha and Western philosophical traditions.

A final challenge to a philosophical approach is the claim that the primary mode of understanding in Western philosophy is reason, whereas for the Buddha enlightenment is achieved not by reason, but by meditation. This is the most interesting objection, and it raises a serious issue that will be one of our principal concerns. Rational thought and discourse have been fundamental to much Western philosophy (though not all of it), and Buddhist meditation has played no role in its traditions. However, both the Buddha and many Western philosophers held that objective knowledge of reality and of how to live may be achieved by human beings. The teaching of the

Buddha challenges the belief, so typical in Western philosophy, that rational reflection is the main means of attaining this knowledge. The Buddha thought reason was valuable but insufficient for enlightenment, and he thought meditation was crucial. The meditation techniques he taught were intended to develop our powers of concentration and, in a special sense, observation. They were meant to take us beyond ordinary modes of understanding, but not outside all understanding. The fundamental role of meditation in the Buddha’s teaching should be seen not as precluding an inquiry into this teaching from a Western philosophical perspective, but as providing a key issue for consideration in this inquiry. As we seek to make sense of the teaching of the Buddha, one of our concerns will be to determine if we have something to learn from meditation. Perhaps the primacy of reason commonly asserted by Western philosophers is ill-advised.

2 Guidelines for learning from the Buddha

It will help to have some guidelines for comprehending and assessing the Buddha’s teaching in a philosophical way. These guidelines are not beyond controversy. We will need to consider one critique from the Buddha himself. Nonetheless, it is important to begin our inquiry with an awareness of some of the methodological issues involved in seeking to understand and evaluate his teaching. These two activities cannot be completely separated: evaluation obviously presupposes understanding, but we cannot fully understand something without recourse to evaluation. However, we will proceed by first discussing some principles of interpretation and then turning to some standards of assessment. In the next section (see pages 11–13), we will reconsider these in light of the Buddha’s own pronouncements apropos the comprehension and evaluation of his teaching.

Objectivity

Our first goal is an accurate and insightful understanding of the Buddha’s teaching. We should assume neither that a perfectly objective account is possible nor that any interpretation is as good as another. As we strive to understand, we are influenced by our own perspective, an ensemble of outlooks, interests, feelings, and capacities rooted in the particulars of our historical, social, and personal circumstances. This is inevitable and not entirely cause for regret. Without some perspective, we could not comprehend anything – for example, we could not understand without language, and whatever languages we know are the products of specific cultures and traditions. Since each of our perspectives differ in important ways, none of us can expect a fully objective account. On the other hand, we should not infer from this that all interpretations are on a par. We need not suppose there is a single correct interpretation to realize that some accounts may be better than others.

Even if conflicting interpretations are sometimes equally or incommensurably good, our goal should be to seek an understanding that is well-founded and illuminating. One reason for being aware of our own perspective is to ascertain the ways it both enables and hinders us from achieving this goal. Though we cannot escape our perspective, we can gain some distance from it and perhaps modify it. This may enable us to overcome some of our limitations and to understand the Buddha in a more accurate and penetrating way.

Honesty

We should be careful not to presume either that the Buddha’s teaching must be pretty much the same as what we already believe or that it has to be radically different from what we think. Both mistakes have been made by some Western interpreters. For example, if we assume that all religions are really saying the same thing in the end, we may fail to see the deep differences between Buddhism and Christianity. Or if we suppose that the ‘Eastern mind’ is essentially different from the ‘Western mind,’ and that ‘never the twain shall meet,’ we may miss the fact that the Buddha addressed concerns of great importance to us. We need to be honest about what he did and did not say. Our aim should be to carefully determine the differences and similarities that actually exist between his teaching and our own beliefs. We may discover that there are real disagreements that must be acknowledged, but we may also find out that there is more common ground than we suspected.

Translation

The Buddha’s words were first recorded in the ancient language Pāli, and were later translated into other languages such as Chinese and Tibetan. We will rely on translations from the Pāli canon. We should assume neither that no adequate translations are possible nor that the translations we have are without drawbacks. There are fairly accurate translations of most Pāli words into English, but often these are only approximately correct. Nuances of a Pāli word may be lost in its English counterpart, or connotations of the English word may be inappropriate to the Pāli term it translates. For example, the crucial term ‘dukkha’ is commonly translated as suffering (as it is here), but this is misleading since ‘dukkha’ has broader implications suggesting lack of satisfaction, contentment, or fulfillment. We need to be aware of such limitations. For some central terms, any translation is potentially misleading. In some cases – especially ‘kamma’ and ‘Nibbāna’ (‘karma’ and ‘Nirvāṇa’ in Sanskrit) – we will follow the custom of leaving the words untranslated and providing a commentary on their meaning. There is a glossary of some important Pāli terms beginning on page 202.

Context

We have to pay attention to the context of the Buddha’s teaching in several respects. First, we need to know something about the culture in which he lived, the circumstances of his life, and the concerns and capacities he had. Second, each part of his teaching can be understood fully only by reference to the whole, and conversely a proper understanding of the whole requires an understanding of each of the parts. Hence, we need to alternate between an examination of the whole and an interpretation of the parts. Third, in our texts the Buddha usually addresses a specific audience (for example, many are followers, but some are critics). To understand a particular text, it may be important to know something about the identity of the Buddha’s interlocutors. The first two issues will be facilitated to an extent in the next two chapters, which contain an account of the Buddha’s life and an overview of his teaching. It is difficult to do justice to the final issue in an introductory discussion, but it will sometimes be significant.

Empathy and criticism

A good way to develop our understanding of the Buddha’s teaching is to employ a dialectic of empathy and criticism. We should begin by trying to hear what the Buddha has to say. This requires attempting, as much as possible, to set aside our own perspective and to empathetically and imaginatively place ourselves in his perspective. The goal here is to figure out why the teaching made sense to the Buddha. The next step is to return to our standpoint and think critically about the teaching. Here the purpose is to raise some hard questions about, for example, the plausibility, coherence, or relevance of the Buddha’s thought. Once these questions have been formulated, it is essential to go back to the mode of empathy to sympathetically determine the extent to which the Buddha may be able to answer our questions. This might lead us to realize there is more to his teaching than we first thought. For example, the search for coherence may lead us to discover something new. We should then return to the critical perspective, and so on and so forth. By moving back and forth between empathy and criticism, we hope to achieve a deeper understanding of the Buddha’s teaching, one that gets beneath the surface meaning and goes to the heart of what is being proposed. There are two dangers: being critical too soon, so that we deprive ourselves of the opportunity to hear what is being said, and not being critical soon enough, so that we postpone asking penetrating questions that may bring out the real meaning of the teaching.

We see in this dialectic one reason why understanding and evaluation are not separate activities. Let us now consider some guidelines for assessing the Buddha’s teaching.

Cosmopolitanism

We should not dogmatically assume our culture is best and provides not only the correct beliefs and values, but also the proper standards for evaluating these. Whatever ‘our culture’ refers to, it is something heterogeneous, contingent, changing, and influenced by other cultures. It is unlikely that it supplies definitive standards that are incapable of improvement. When we find disagreement with the Buddha, one possibility is that he is mistaken, but another is that we are. Though we cannot help but begin with our own outlook, we need not end up with the same outlook, at least not without modification. On the other hand, we should not make the opposite mistake and assume that everything distinctive in our culture is corrupt and in need of correction by, for example, the ancient and flawless wisdom of the Buddha. There is no substitute for reflecting on whether something is sound, whether it comes from our culture or another.

Open-mindedness

A related point is that we should not assume either that the teaching of the Buddha cannot possibly make sense because it seems so strange and difficult to comprehend, or that it must make sense because Buddhists have lived their lives in accordance with it for thousands of years. We need to be open to the possibility that there is great insight and value in the Buddha’s message, but also to the possibility that it has limited worth.

Coherence

If the teaching of the Buddha appears to lack coherence, this should give us pause. In the most obvious case, if one part contradicts another part, the teaching as a whole cannot be entirely true. Faced with an apparent contradiction, we need to consider whether it can be resolved (for example, by showing that the two parts do not really contradict one another, or that we have mistakenly attributed one of them to the Buddha). Coherence does not guarantee truth, but lack of coherence is a sign that something is probably amiss. Hence, we need to reflect regularly on whether the Buddha’s teaching is coherent. Here especially interpretation and evaluation should work hand in hand.

Fidelity to our experience

If there is something to learn from the Buddha, then at some point and in some way his teaching must connect with our own experience. It must show itself to be a relevant and compelling analysis of our lives – as the Buddha himself would be the first to insist. However, we should not suppose that what the Buddha says will be immediately obvious. In fact, he gives reasons for being suspicious of what we think is obvious. But sooner or later, if we are to discover something important in the Buddha, his teaching must illuminate our deepest concerns, values, aspirations, feelings, and the like.

Selectivity

Finally, we need not suppose that we must accept or reject the teaching of the Buddha as a whole. Perhaps we can learn from some aspects of it, but not others. Historically, as Buddhism entered different cultures, it developed in diverse and sometimes conflicting directions. Often the Buddha’s teaching was integrated into a native tradition in such a way that the teaching modified the tradition and the tradition also modified what was thought worthwhile in the teaching. For example, Japanese Zen Buddhism is rooted in the Buddha’s teaching, but it is a distinctive cultural formation that differs significantly from many other forms of Buddhism. We should not assume our situation is any different. Understanding parts of the teaching requires consideration of the whole, but we might discover that some parts are more valuable to us than others.

3 The guidelines, the Eightfold Path, and the stream-observer

The guidelines just outlined express principles that I believe are reasonable in light of contemporary Western debates about methodology (discussion of these issues is often called hermeneutics). It would take us too far afield to consider recent critiques of these guidelines, but it is pertinent to our inquiry to ask to what extent they comport with the teaching of the Buddha. He was much concerned that his teaching be properly understood and evaluated. For example, just before his death he said to his followers that, if someone attributed a particular teaching to him, then ‘without approving or disapproving, his words and expressions should be carefully noted and compared with the suttas [his discourses] and reviewed in the light of the discipline.’ He said the purported teaching should be considered ‘the word of the Buddha’ if and only if it conformed to the suttas and discipline (L 255). With respect to evaluation, the Buddha encouraged his followers to ‘examine the meaning of [his] teachings with wisdom’ in order to ‘gain a reflective acceptance of them’ (M 227).

These passages show an awareness of methodological issues, but the Buddha did not teach anything comparable to the guidelines stated in the last section. However, there is reason to think he might have accepted, or at least might not have had reason to reject, many of these guidelines. The passages just quoted express a concern for objective understanding and reflective evaluation that is spelled out in many of the guidelines. Moreover, several of these principles recommend a middle position between two extremes. This is in the spirit of a central motif in the Buddha, the idea that his teaching is a middle way. In addition, the contextual principle that interpretation of a passage may require reference to the Buddha’s audience has long been a standard precept, taken to be implicit in his teaching, of ‘Buddhist hermeneutics’ (as it is called in the West). Of course, there are also some obvious differences. The Buddha did not have the concern about the influence of cultural and historical location on interpretation that is so common nowadays. Moreover, his convictions about the limitations of language in describing Nibbāna may challenge the extent to which coherence is a viable criterion in this respect. And he did not suggest that we might be selective in learning from his teaching.

Nonetheless, the central point to make in comparing the guidelines of the last section and the teaching of the Buddha is this: instead of proposing any such guidelines, the Buddha taught the Noble Eightfold Path (ariya aṭṭhangikamagga) to enlightenment, and he believed that only someone fully enlightened could properly understand and evaluate his teaching. The Eightfold Path is a long, complex, and difficult regime that is intended to radically transform us by means of an array of intellectual, moral, and meditative disciplines. Undertaking the path requires a long-term commitment. We cannot try it out for a few weeks and quickly see how well it works. For someone new to the teaching who is wondering if there is something to learn from the Buddha, a central question is whether there is any reason to make such a commitment in the first place. This person is not helped by being told that the ultimate standpoint for understanding and evaluating the teaching is only available to someone who has followed the Eightfold Path and achieved enlightenment. A person initially encountering the Buddha’s teaching needs some advance assurance that there is truth in this teaching if he or she is to go farther. It is for this person that the guidelines in the last section are important. Following these guidelines might provide someone with this advance assurance. If it did, this person would have reason to undertake the Eightfold Path, and the training of the path may be expected to supersede the guidelines. (An interesting question, however, is whether the modern perspective expressed in the guidelines might give a contemporary follower of the Buddha reason to modify the Eightfold Path or our interpretation of it.)

The Buddha agreed that some initial assurance was required before beginning the Eightfold Path. He did not propose that people undertake it on blind faith. There is reason to think he might have been in broad agreement with many of the guidelines, understood not as a substitute for the Eightfold Path, but as instruments for determining whether or not to begin it. It will be convenient to have a label for the person contemplating this. The Buddha classified persons already on the path according to four levels of achievement towards full enlightenment. He called the lowest of these the stream-enterer (sotāpanna) – someone who has begun the journey across the river whose opposite shore represents enlightenment. Since a stream-enterer is someone who already has confidence in the Buddha’s teaching, let us call a person who is considering whether such confidence is warranted a stream-observer: this is someone standing on the shore wondering whether enlightenment is really the reward of the difficult journey across.

The concerns of stream-observers will vary according to the specific perspective each brings to the teaching of the Buddha. In this book, the stream-observers I have in mind are primarily those who are culturally part of the contemporary Western world and have no Buddhist upbringing. Of course, this is a large group of persons with many different and often conflicting viewpoints. Nonetheless, there are some characteristic questions such persons may be expected to ask. I will endeavor to formulate these questions and consider what the Buddha might be able to say in response. My purpose is not to argue that Western stream-observers should or should not strive to become stream-enterers, but to provide them with some guidance for making this decision for themselves, and more broadly for determining what they might learn from the Buddha.

The promise and great attraction of the Buddha’s teaching is a life of happiness, compassion, and tranquillity. But for stream-observers there are likely to be many serious obstacles to understanding and appreciating this teaching. These include the moral rigors of the Eightfold Path, the practice of meditation, and ideas such as rebirth, impermanence, non-attachment, Nibbāna, and especially the not-self doctrine. We need to consider whether, or to what extent, such obstacles can be overcome.

4 A word about sources

A brief account of the sources of our knowledge of the Buddha’s teaching is in order. The Buddha wrote nothing: his teaching was communicated orally over a period of 45 years some 2,500 years ago. According to tradition, shortly after the Buddha’s death, 500 enlightened followers (arahants) met in Rājagaha, India for a communal recitation of his teaching. This was divided into two parts now known as the Vinaya Piṭaka (‘Discipline basket’) and the Sutta Piṭaka (‘Discourse basket’). The recitations were led respectively by UPāli and Ānanda, thought to be especially well-qualified to accurately remember what the Buddha taught. The Vinaya Piṭaka contains detailed rules of conduct governing the monastic community the Buddha founded. The Sutta Piṭaka consists mainly of discourses the Buddha delivered to explain his teaching. These rules and discourses were committed to memory and transmitted orally from generation to generation. About a century later, various factions began to emerge, each with its own somewhat different understanding of the Buddha’s teaching. During this time, a third genre of the teaching developed, the Abhidhamma Piṭaka (‘Higher teaching basket’). This contains a more systematic and abstract exposition and interpretation of what the Buddha taught. With this, the entire body of teaching – the Vinaya, Sutta and Abhidhamma Piṭakas – came to be known as the TiPiṭaka (‘Three baskets’). However, it was not until later, perhaps the first century BCE, that this teaching was first committed to written form, and it was much later yet that modifications of this canon came to an end. There now exist several versions of the TiPiṭaka in different languages, and while they substantially overlap, they are not identical. In short, we do not have direct knowledge of the teaching of the Buddha. Instead, we have a large and diverse body of texts that purport to represent his teaching, but which are the product of a long period of oral transmission from memory as well as translation from one language to another. The distance from the Buddha’s mouth to the texts we now possess is considerable (more so than in the case of written accounts of the teaching of Socrates or Jesus), and there is much room for modification and misunderstanding. To a limited extent, modern scholarship may inform us when texts are more or less likely to accurately represent what the Buddha really thought. But there is little prospect that we will ever know in detail how closely extant texts correspond to his actual teaching.

However, for our purposes we will follow tradition and consider the teaching of the Buddha to be the teaching expressed in these texts. We have no other access to what he said, and these texts probably accurately represent his instruction on the whole. Moreover, it is the teaching conveyed in the TiPiṭaka that has been influential in the world: what we now call Buddhism is fundamentally rooted in these texts and the various traditions that have interpreted them. (It should be recognized, though, that some traditions such as Mahāyāna Buddhism emphasize later texts, and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism is skeptical about the value of texts.)

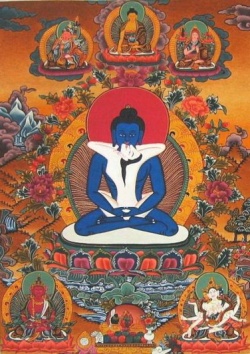

The main versions of the TiPiṭaka available today are the Pāli, Chinese, and Tibetan canons. We will rely on the Pāli canon. In overall comparison with the other two, it is probably older, less interpretive, and closer to the language of the Buddha (it is not known exactly what language he spoke, but Pāli, a Middle Indo-Aryan language related to Sanskrit, has historical connections with it). Moreover, unlike the other canons, we have full, and for the most part readily available, translations into English of the relevant Pāli texts. The Pāli canon is the authoritative canon of the Theravāda tradition that prevails in Sri Lanka and parts of Southeast Asia. The purpose is not to side with this tradition in contrast with other Buddhist traditions, but to employ the texts of its canon to understand and evaluate the Buddha’s teaching. In an introductory inquiry, this is the most sensible course. But it is not perfectly neutral. Though the Theravāda tradition takes the Pāli canon to express the original teaching of the Buddha, it is still the result of a long, interpretive history. Of the three parts of the TiPiṭaka, we will focus on the Sutta Piṭaka. The Vinaya Piṭaka has great practical significance for Buddhist monastic communities, but it is comparatively less important for understanding the philosophical aspects of the Buddha’s teaching. By contrast, the Abhidhamma Piṭaka contains what in some respects are the most philosophical presentations of the TiPiṭaka. However, the detailed, systematic, and abstract formulations of these texts, and their concern with doctrinal disputes, are the product of interpretations subsequent to the Buddha’s life. Though they are considered by the Theravāda tradition to be the word of the Buddha, they are less close to his actual teaching than the other parts of the TiPiṭaka and essentially mark the beginning of commentaries that have continued to this day. The Sutta Piṭaka purports to represent the actual teaching of the Buddha, for the most part on specific occasions to particular persons. Typically a sutta (discourse) begins with the phrase, purportedly of Ānanda at the first recitation, ‘Thus I have heard,’ followed by a description of a place and an audience. The main body of the text consists of a teaching of the Buddha, usually expressed by the Buddha himself, but sometimes by one of his chief disciples such as Sāriputta. Often at the end, there is a declaration by the person addressed expressing confidence in the truth of the teaching. Though the suttas as we have them are partly the product of later interpretation, they are probably the texts available to us that come closest to expressing the philosophical aspects of the actual teaching of the Buddha. The Sutta Piṭaka is divided into the following five collections of texts called Nikāyas (‘Groups’):

- Dīgha Nikāya (‘Long Discourses’)

- Majjhima Nikāya (‘Middle Length Discourses’)

- Saṃyutta Nikāya (‘Connected Discourses’)

- Aṅguttara Nikāya (‘Numerical Discourses’)

- Khuddaka Nikāya (fifteen short texts with various titles).

Information about translations of these texts may be found in the Bibliography. We will mainly be concerned with the first four of these. The Khuddaka Nikāya consists of a miscellaneous group of texts, though these include popular works such as The Dhammapada, and also the Therīgāthā, an important representation of the voices of women followers of the Buddha.

Taken as a whole, the Sutta Piṭaka is incredibly long and repetitious. Moreover, except for the Saṃyutta Nikāya, the method of organization is largely non-thematic and hence not user-friendly. The beginning student of the Buddha who reads these texts without guidance is likely to become discouraged very quickly. To mitigate this problem, at the end of each chapter I recommend some suttas as particularly relevant to that chapter (see the ‘Suggested reading’ sections). Readers are strongly urged to study these suttas in conjunction with this book. To the extent feasible, I have chosen these recommendations from the Majjhima Nikāya: if there were one substantial text with which to begin, this would probably be it. (However, the English translation runs over 1,100 pages.) I have also cited passages from the Majjhima Nikāya in preference to parallel passages elsewhere whenever possible. But texts from other parts of the Sutta Piṭaka have been recommended and cited when necessary.

SUGGESTED READING

No specific sutta is uniquely appropriate to this introductory chapter, but the reader might start with The Dhammapada, especially chapters 9, 14, 15, 16, 20, 24, and 26. For our purposes, this inspirational anthology of sayings has limited value, but it does provide an initial taste of the practice the Buddha taught. There are numerous translations (see Bibliography for references to two of these – page 206). For an introduction to this work, see Kupperman (2001). Dissanayake (1993) offers an interesting analysis.

Accounts of the emergence of Buddhism in the West can be found in Batchelor (1994), Fields (1992), Harvey (1990: chapter 13), Keown (1996: chapter 9), Mitchell (2002: chapter 11), and Strong (2002: chapter 10).

For discussion of methodological issues, see Larson and Deutsch (1988), Mueller-Vollmer (1985), and Nussbaum (1997: chapter 4). Methodological questions in the study of Buddhism are considered in Garfield (2002: chapters 13 and 14), Hoffman (1991), Lopez (1988), and Maraldo (1986). A useful resource for important terms in the Pāli canon is Nyanatiloka (1988).

NOTE

1 Māhāyana Buddhism speaks of numerous Buddhas who exist in various ‘Buddha fields.’ However, the term ‘the Buddha’ ordinarily refers to Siddhattha Gotama (also called Śākyamuni Buddha).

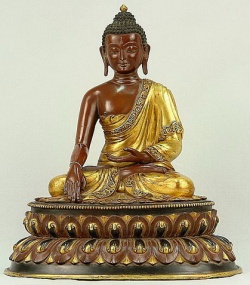

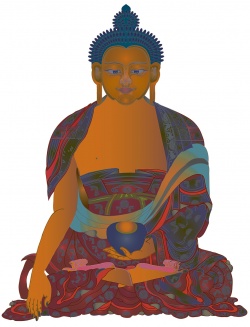

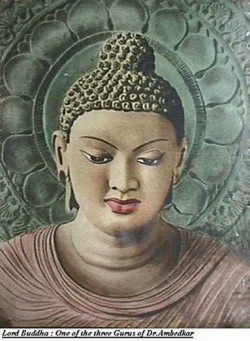

THE LIFE OF THE BUDDHA

The life of the Buddha is a constitutive part of his teaching. In this respect, it is natural to compare the Buddha with other primordial figures such as Socrates and Jesus, teachers who conveyed their beliefs with the whole of their lives, but wrote nothing. In all three cases, there was much oral communication that was preserved by memory and subsequently recorded by enthusiastic followers. But these three personages intended to teach with their actions as well as their words, and we cannot properly understand these words, in the canonical texts of their adherents, without placing them in the context of the lives of those who expressed them.

The Buddha’s life, as it has been passed down to us in Buddhist traditions, is surely rooted in historical fact, but it has been embellished by the imaginative inventions of devoted disciples. There is little prospect of clearly and fully separating literal truth from supplemental fiction in these accounts, and in any case the apparent amendments are often symbolically significant even if historically false. In order to learn from the Buddha, stream-observers first need to listen sympathetically to the story of his life and attempt to feel its power as countless generations of persons in Buddhist cultures have felt it. Subsequently they should reflect critically on its meaning.

The narrative recounted here contains the main features standardly included in traditional accounts, with an emphasis on those aspects especially important to understanding the Buddha’s teaching. His life had three distinct phases: the early years culminating in the realization of human suffering, the search for and attainment of enlightenment concerning this suffering, and the fulfillment of his commitment to devote the remainder of his life to instructing others how to achieve enlightenment for themselves.

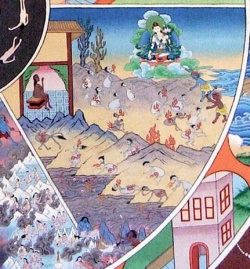

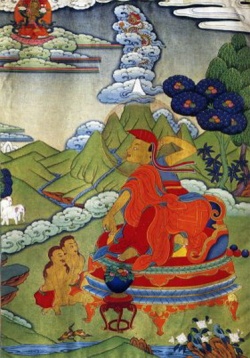

1 The discovery of human suffering

The person we know as the Buddha was born in the Lumbinī grove, in the vicinity of Kapilavatthu, near the present-day border of India and Nepal, sometime between the seventh and the fifth centuries BCE. He was called Siddhattha Gotama (Siddhārtha Gautama in Sanskrit). In view of the doctrine of rebirth, it should not surprise us that this was not his first birth, though it was to be his last. In one of his previous lives, when he was called Sumedha, he met someone already enlightened, already a Buddha. Sumedha vowed to strive for enlightenment himself. He became a bodhisatta, a being devoted to seeking enlightenment. But he was to achieve enlightenment only after many rebirths during his life as Siddhattha. (The name ‘Siddhattha’ means ‘One who achieves his goal’.)

Siddhattha’s father, Śuddhodana, was a relatively powerful and wealthy leader of a small tribe called the Sakka, structured more as a republic than a kingdom, and located in the Ganges river basin near the foothills of the Himalayan mountains (Kapilavatthu was its capital). His mother Mahāmāyā died a week after his birth, and he was raised by Mahāpajāpatī, an aunt who became his father’s second wife. Little is known of Siddhattha’s early life. Presumably he was raised in considerable prosperity and received a good education by the standards of the time. He was also reputed to have been extremely attractive physically. Aged sixteen, he married the beautiful Yaśodharā. Several years later, when he was twenty-nine, she gave birth to their first (and, it would turn out, only) child, their son Rāhula. That Siddhattha was married, had a son, and was probably in line to acquire the power and wealth of his father no doubt made him a very fortunate and much envied young man in Sakka.

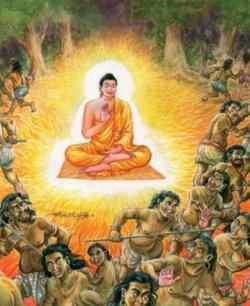

At the time of his birth, religious authorities observed that Siddhattha possessed the ‘thirty-two marks peculiar to a Great Man’ (L 441) and they predicted that he would become an important world figure, either a just ruler or an enlightened spiritual leader. His father was determined that he should become a ruler, and to ensure this outcome he protected his son from everything unpleasant in life. An early omen should have warned Śuddhodana that his son had a different destiny. At the age of twelve, Siddhattha was found meditating under a tree during a festival. Eventually, he discovered what everyone comes to know – that there is suffering in human life. One day he left the palace and saw a decrepit, bent-over old man walking with a stick to support him. Thus Siddhattha realized that human beings are not forever young: we all age and grow old. On a second outing, he saw a man who was extremely ill. Thus Siddhattha realized that human beings are not forever healthy: we are all liable to sickness. On a third excursion, he saw a dead man in a funeral procession. Thus Siddhattha realized that human beings do not live forever: we all die eventually.

The threefold discovery that aging, illness and death are facts of every human life was a shock to Siddhattha. He was overcome with disgust and shame (N 54). He wondered: What is the meaning of human suffering? What is its cause? Can it be overcome? How can such questions be answered? On a fourth outing, Siddhattha saw a man who had left home, shaved his head, and donned yellow robes: he was seeking a life of wisdom, virtue and tranquillity outside the conventional life of society, and he became an initial role-model for Siddhattha. The Buddha said later:

- While still young, a black-haired young man endowed with the blessing of youth, in the prime of life, though my mother and father wished otherwise and wept with tearful faces, I shaved off my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and went forth from the home life into homelessness.

- (M 256)

This was the beginning of Siddhattha’s effort to understand human suffering. He was twenty-nine years old and would persist for six years before attaining enlightenment.

2 The quest for enlightenment

Siddhattha began his search by seeking instruction from persons who were reputed to be wise. The dominant religion in his society was Brahmanism, a forerunner of Hinduism based on a set of oral teachings known as the Vedas (their origin goes back as far as around 1,500 BCE). There are three features of Brahmanism worth noting here. First, it maintained that all persons were determined by birth to fall into exactly one class in a hierarchy of four: the religious leaders known as brahmins, rulers and warriors, farmers and traders, and servants (this is the ancestor of the later caste system in India). Second, Brahmanism accepted polytheism and supposed that benefits from the gods could be obtained by sacrificial rituals. Third, it emphasized the value of ascetic practices as well as meditation techniques known as yoga. As the Buddha, Siddhattha would be critical of the first two of these tenets, but he would incorporate and transform both features of the third. It is especially significant that, as he began his quest, he found himself in a world in which meditation was already regarded as an important spiritual discipline. It was with two teachers of meditation that he embarked on his quest for understanding.

The first was Āḷāra Kālāma. Siddhattha quickly learned Kālāma’s teaching and attained the highest meditation level in his system – what he called ‘the base of nothingness’ (M 257). In fact, Kālāma was so impressed by Siddhattha’s achievements that he offered him co-leadership of his community. But Siddhattha was not satisfied with what he had achieved. This teaching, he said, ‘does not lead to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation, to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna’ (M 258).

His second teacher was Uddaka Rāmaputta. Once again, Siddhattha rapidly understood his teaching and achieved the highest level of concentration, the ‘base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception’ (M 258). This time his teacher was so taken with his accomplishments that he offered him leadership of his group. But as before, Siddhattha was similarly dissatisfied. He moved on, though the two aforementioned levels of concentration were later included in his own system of meditation.

Siddhattha lived during a period of spiritual unrest. The ideas of the Upaniṣads were emerging and there were many who challenged Brahmanism on a variety of philosophical fronts (the first sutta of the Dīgha Nikāya describes sixty-two different philosophical views). The Jains accepted a doctrine of kamma, rebirth, and liberation from rebirth; they also claimed that all things are alive and opposed every form of violence. The Ājīvikas were fatalists who believed our future lives were predetermined and beyond our control. There were also materialists who denied any life beyond this one. The Buddha would call this view annihilationism (ucchedavāda) in contrast to the eternalism (sassatavāda) of the previous two positions. And there were skeptics, described by the Buddha as ‘eel-wrigglers,’who concluded we could not know which of the competing views was correct and advocated believing none of them. The Buddha would challenge each of these positions, but he would also draw on aspects of some of them, especially those of the Jains. What is significant at this juncture is that some proponents of these outlooks left their communities, lived on alms, and practiced extraordinarily severe regimes of asceticism and meditation. They were known as samaṇas – reclusive spiritual strivers. It was his observation of one of the samaṇas that inspired Siddhattha’s own quest for enlightenment after his fourth excursion from the palace.

Having departed from his two more conventional teachers, Siddhattha joined company with five samaṇas. Among them he practiced asceticism with a vengeance, bringing himself to ‘a state of extreme emaciation’ and nearly to the point of death by eating almost nothing (M 339). In addition, he undertook a ‘breathless meditation’ he described in these words: ‘I stopped the in-breaths and out-breaths through my mouth, nose, and ears. While I did so, violent winds cut through my head. Just as if a strong man were splitting my head open with a sharp sword’ (M 337–8). But it was all to no avail. Eventually, after nearly six years, Siddhattha reached the conclusion that ‘by this racking practice of austerities I have not attained any superhuman states, any distinction in knowledge and vision worthy of the noble ones.’ He asked, ‘could there be another path to enlightenment?’ Thinking there must be, he began to eat food provided by a young woman named Sujātā, and his five ascetic companions left him, disgusted that he had ‘reverted to luxury’ (M 340).

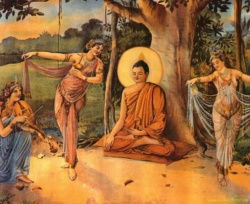

Once nourished, Siddhattha sat under a tree later known as the ‘Bodhi-tree’ (tree of awakening) and he began to reflect and meditate, determined to achieve enlightenment on his own. According to later accounts, a final obstacle remained. Māra, a tempter somewhat like Satan, but representing not so much evil as the forces of desire and their propulsion of us into repeated rounds of death and rebirth, strove mightily to divert Siddhattha with the promise of sensual enchantments and the threat of physical torments. Siddhattha held firm. Māra then challenged Siddhattha’s belief that he was now prepared for enlightenment. Siddhattha insisted that his good works and spiritual attainments were sufficient preparation, and he touched the ground with his right hand to bid the earth to bear witness to his claim. The earth shook. Māra fled in defeat. Siddhattha was now ready.

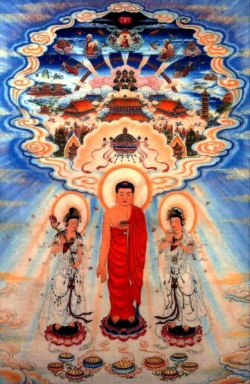

He promptly passed through four levels of concentration, the four jhānas that are a key part of Buddhist meditation. Siddhattha’s mind was thereby ‘purified, bright, unblemished, rid of imperfection.’ He then attained three kinds of knowledge. The first was specific knowledge of his own past lives. The second was knowledge of the passing away and reappearance of beings, those who lived well in a ‘good destination,’ and those who did not in a ‘state of deprivation.’ The third and most important was knowledge of the nature of suffering, its origin, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation – what he would call the Four Noble Truths (ariya sacca), the heart of his teaching. Thus his mind was liberated from the taints (āsava) of sensual desire, being, and ignorance. He had achieved enlightenment: ‘Ignorance was banished and true knowledge arose, darkness was banished and light arose.’ Siddhattha was now a buddha, an enlightened one who had rediscovered liberation from the cycle of rebirth and suffering. He declared, ‘I directly knew: “birth is destroyed, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more coming to any state of being” ’ – a somewhat cryptic allusion to Nibbāna we will come to understand (M 105–6).

3 The life of teaching

For the most part, the Buddha – as we may now call Siddhattha – is not portrayed as growing in wisdom or virtue after his enlightenment. The transformation under the Bodhi-tree was radical and complete, and these qualities could not be improved upon further. But there was one moment immediately after his awakening when the Buddha did undergo a significant change. He first believed that the Dhamma, the understanding of the ultimate reality and correspondingly correct way of life he had now achieved, was too difficult for people to grasp in their present condition and that it would not be worthwhile to teach them:

- This Dhamma that I have attained is profound, hard to see and hard to understand, peaceful and sublime, unattainable by mere reasoning, subtle, to be experienced by the wise. But this generation delights in adhesion [to sense pleasures), takes delight in adhesion, rejoices in adhesion. It is hard for such a generation to see this truth . . . . If I were to teach the Dhamma, others would not understand me, and that would be wearying and troublesome for me.

- (M 260)

Hence, the Buddha was ‘inclined to inaction rather than to teaching the Dhamma.’ At that moment, however, the Brahmā Sahampati appeared and declared to the Buddha: ‘There are beings with little dust in their eyes who are wasting through not hearing the Dhamma. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.’ In response to this appeal, the Buddha decided to teach what he had learned ‘out of compassion for beings’ (M 260–1). He was aged thirty-five and would spend the remaining forty-five years of his life teaching the Dhamma to all who would listen so that they themselves might achieve enlightenment and overcome suffering.

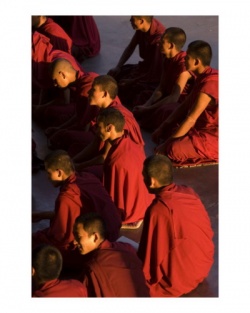

The Buddha’s initial thought was to return to his first two teachers, Kālāma and Rāmaputta, but they had both died recently. He then sought out the five ascetic saman. as he had abandoned earlier. They were suspicious at first. After all, they thought, their former companion had succumbed to luxury and so could not be a true spiritual striver. They refused to pay him homage but did allow him to sit down. The Buddha declared that he had not given in to luxury, that he had not abandoned striving, and that in fact he had achieved enlightenment. It was to this group of five that the Buddha gave his first sutta, ‘Setting in motion the wheel of Dhamma.’ Its focus was the Four Noble Truths, culminating in the Eightfold Path leading to the cessation of suffering. The Buddha described this path as a ‘middle way’ (majjhimā paṭipadā) between the worldliness of most persons and the asceticism of the samaṇas. In short order all five were convinced. They became arahants, fully enlightened ones, and they were the Buddha’s first followers.

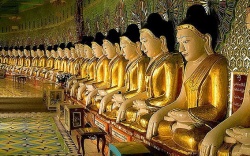

He soon attracted a large group of male disciples called bhikkhus. Like the Buddha, they had left home and family to seek enlightenment, and with the Buddha, many found it. They lived together in the Sangha, a highly disciplined, celibate community that was supported by alms. The common translations of the terms ‘bhikkhu’ and ‘Sangha’ as monk and monastic order respectively are not inappropriate if we keep in mind qualifications to be made in understanding Buddhism as a religion (see chapters 4 and 5). Five years later, upon the urging of his step-mother Mahāpajāpatī and his attendant Ānanda, the Buddha established a community of female disciples, the bhikkhunīs, or nuns. This was a second important post-enlightenment development in the Buddha’s thinking. In addition to the bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, there were male and female lay followers – upāsakas and upāsikās – who did not leave home but nonetheless strove to live according to the teaching of the Buddha.

The Buddha spent the remainder of his life travelling on foot in the vicinity of the Ganges river basin, in the company of many disciples, teaching to whomever would listen, irrespective of class or gender. In his eightieth year, he fell ill (possibly from food poisoning) and realized he was dying. The Tathāgata, a common epithet for the Buddha meaning literally ‘thus come one, thus gone one,’ first informed Ānanda:

- Have I not told you before: All those things that are dear and pleasant to us must suffer change, separation and alteration? So how could this be possible? Whatever is born, become, compounded, is liable to decay – that it should not decay is impossible. And that has been renounced, given up, rejected, abandoned, forsaken: the Tathāgata has renounced the life-principle. The Tathāgata has said once for all: ‘The Tathāgata’s final passing will not be long delayed. Three months from now the Tathāgata will take final Nibbāna.’

- (L 252–3)

The Buddha appointed no successor. Through Ānanda, he instructed the bhikkhus to ‘live as islands unto yourselves, being your own refuge, with no one else as your refuge, with the Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as your refuge, with no other refuge’ (L 245). He also said to them that his teaching ‘should be thoroughly learnt by you, practiced, developed, and cultivated, so that this holy life may endure for a long time, that it may be for the benefit and happiness of the multitude, out of compassion for the world’ (L 253).

On the night of the Buddha’s death, in the small village of Kusinārā, a wanderer named Subhadda asked to speak with him. He had a doubt he hoped the Buddha could dispel. Over the objection of Ānanda, the Buddha agreed to see him. The Buddha emphasized to Subhadda, as he had earlier to so many others, the importance of the Eightfold Path as the distinctive feature of his teaching. Subhadda declared, as had so many before, ‘It is as if someone were . . . to point out the way to one who had got lost, or to bring an oil lamp into a dark place, so that those with eyes could see what was there’ (L 268–9). Thereupon Subhadda became an arahant, the final personal disciple of the Buddha.

The Buddha was now confident all questions among the bhikkhus were resolved. To them he addressed his final words: ‘All conditioned things are of a nature to decay – strive on untiringly’ (L 270). With this, the Buddha passed to final Nibbāna. Those bhikkhus ‘who had not yet overcome their passions wept and tore their hair, raising their arms, throwing themselves down and twisting and turning.’ But those bhikkhus ‘who were free from craving endured mindfully and clearly aware, saying: “All compounded things are impermanent – what is the use of this?” ’ (L 272). Following instructions he had left behind, seven days after his death, the body of the Buddha was cremated on a stupa in the manner of a king.

4 Reflecting on the Buddha’s life

We will probably never know to what extent our understanding of the Buddha’s life is historically accurate. No biography was written during or near his lifetime. Most of the details just recounted are found in the Sutta Piṭaka, but some appear only later. Moreover, these texts are the product of an oral tradition lasting several generations before they were written down, and they include obvious fabrications. My favorite tells us that at birth Siddhattha walked north seven steps, surveyed the world, and declared: ‘I am the highest in the world; I am the best in the world; I am the foremost in the world. This is my last birth; now there is no renewal of being for me’ (M 983). And you think your child is precocious.

We do not even know in which centuries the Buddha lived. Everyone seems to agree that his life lasted eighty years, but there is considerable disagreement about the date of his birth. Dates ranging from the late seventh to the late fifth centuries BCE have been proposed. Most Western scholars think he was born somewhere around 500 BCE. If this were correct, then the Buddha would have lived most of his life in the fifth century BCE. This would mean he lived many centuries after Abraham, around the same time as Confucius, about a century before Socrates, five centuries before Jesus, and eleven centuries before Muhammad. For simplicity, it will be convenient to remember that the Buddha lived approximately 2,500 years before us.

For our purposes, these issues do not matter much. Whatever the precise details of the Buddha’s life, there is broad agreement about its general outline, and it is this life – the life that has been passed down through generations of Buddhists – that is important. For it is this life that is a constitutive part of the teaching of the Buddha as we know it, and it is about this life that we are invited to reflect.

The life of the Buddha might be described in a variety of ways – as a story about someone who lost his mother at birth, who abandoned his wife and child, who rebelled against his father, who forsook worldly for spiritual power, and so on. From these perspectives, there are many questions stream-observers might ask about the Buddha. How did the death of his mother affect him? Were there other perhaps less noble motivations in leaving home? Did he yearn for his wife and child during his long search for enlightenment? Did he ever seek reconciliation with his father? From a personal standpoint, these questions appear especially interesting and important. But they are not the questions the traditional story primarily is meant to raise. This is not because our answers could only be speculative (which is mostly true), but because the story is intended to speak to us in universal terms that do not depend on the specifics of particular personal relationships.

What is important, we are supposed to believe, is that the Buddha had virtually all those things most people seek and suppose will bring them happiness – good looks, wealth, power, prestige, a fruitful marriage, and so on – and he realized that, in fact, these things were insufficient for real happiness. No matter how successful we are in pursuing these apparent goods, it remains the case that each of us will grow old, become ill, and die (unless we die sooner from accidents, natural disasters, or acts of violence). Old age, illness, and death are basic facts of life, and they appear to be inevitable sources of suffering for each of us and for those we love. The Buddha saw this as emblematic of a more general truth: that the goods most persons devote their energies to acquiring are impermanent and so are not by themselves genuine sources of happiness. Hence he looked elsewhere. This is one meaning of his ‘great renunciation,’ his departure from home and family to seek enlightenment.

After a long and arduous struggle, the Buddha believed he discovered that true happiness is achieved precisely where we might think it least likely to be found – in freedom from craving, clinging, and attachment to what we desire. The state of non-attachment is the primary fruit of enlightenment. It is the promised culmination of a difficult and complex journey, an intellectual, moral, and meditative undertaking – the Eightfold Path – that, successfully completed, releases two powerful forces within us: compassion for other living beings and joyful appreciation of each moment of our lives irrespective of what happens to us. These forces have a latent presence in each of us, the Buddha taught, but for most of us, because of our attachments, they manifest themselves only weakly and sporadically. Still, by attaining the state of non-attachment, compassion and joy are made available to each of us, and with these comes tranquillity, the mark of genuine happiness. This is one meaning of the Buddha’s life of homelessness: real happiness is to be found not in the fulfillment of our conventional pursuits, but in a fundamental reorientation of our attitudes towards those pursuits – that is, in freedom from the craving and attachment typically associated with our desires for success.

No doubt stream-observers noticed that, in the end, the Buddha grew old, got sick, and died. He did not purport to have found a way to eliminate these sources of suffering in life as we know it. He did not announce the discovery of a fountain of youth. Rather, he proclaimed that full enlightenment would enable us to achieve happiness in this life despite aging, sickness, and death, and that it would release us from the cycle of rebirth into similar lives so as to attain another form of being free from all suffering. Though it is said to be beyond adequate description in our language, Nibbāna is a state we can achieve while living this life as well as one beyond life as we ordinarily know it.

This is the central message the life of the Buddha is meant to convey: true happiness may be achieved not by gaining what we seek to possess, but by cultivating a state of non-attachment with regard to our desires. This is the message we are meant to apply to our own lives. It is at once powerful and perplexing, powerful because it offers a road to well-being immune to vicissitudes we all recognize, and perplexing – for many, I suspect – for a variety of psychological and philosophical reasons. The Buddha encouraged his followers to understand his teaching for themselves. Stream-observers can do this only by confronting what perplexes them and reflecting on the extent to which this teaching has resources to resolve their concerns. It is thus appropriate to close this chapter by considering one question directly raised by the story of the Buddha’s life.

5 The integration question

After achieving enlightenment, the Buddha wondered whether or not to teach what he had learned, and he decided to teach ‘out of compassion for beings.’

But he did not wonder whether or not to return to Yaśodharā and Rāhula, the wife and child he had left behind six years earlier. He is not portrayed so much as having considered this option. He seemed just to assume he would not return. I do not mean to suggest that we should condemn the Buddha for forever abandoning his wife and child. We should be hesitant about applying our moral standards too quickly and simply to a situation so remote in time and place from our own. In the traditional story, the Buddha presumably is understood as fulfilling a higher calling, for the good of all persons, and it may be observed that his wife and child were taken care of properly (later Rāhula became a disciple).

Nonetheless, there is an issue for us in connection with this aspect of the Buddha’s life. In his teaching, there is a sharp dichotomy between members of the Sangha and lay followers. There is also a reciprocal relationship between them: the Sangha offers spiritual guidance to the lay community, and that community in turn provides material support for the Sangha. But it is the sharpness of this dichotomy that is important here. Because of it, the Buddha could not both lead the Sangha and return to his wife and child. He did not consider such integration to be possible. Why not?

The answer, in brief, lies in the fact that the Buddha tended to regard life in the Sangha as the express train to enlightenment. He often said: ‘Household life is crowded and dusty . . . it is not easy, while living in a home, to lead the holy-life utterly perfect and pure as a polished shell’ (M 448). Seeking enlightenment in a household life is like taking the local train: you may make progress towards your destination, but it will take longer and it is likely there will be many stops – that is, rebirths – along the way; moreover, at one of these stops, you probably will have to change to the express if you are to reach your destination. On this view, enlightenment requires a radical transformation of the person, and for this radical means are necessary – means that typically are possible only in a literal withdrawal, sooner or later, from the ordinary pursuits of family, work, and the like.

No doubt life in the Sangha is an attractive and admirable ideal for some persons. But if this were all there was to say, it would be unlikely that the teaching of the Buddha could have much personal meaning for most people, especially stream-observers in the West. Even among persons impressed by this teaching, very few are prepared to enter the Sangha. If monastic life were the only way to truly follow the Eightfold Path, to genuinely seek enlightenment, this path is one nearly all would forego (at least in this lifetime!), regardless of its promise of real happiness. In fact, much of the teaching of the Buddha was directed primarily to members of the Sangha. In this respect, his lack of interest in returning home appears to carry great significance.

But perhaps there is more to say. The Buddha did teach that enlightenment was possible for all persons, he did welcome and encourage lay disciples, and he did say, shortly before his death, that ‘more than fifty lay-followers have . . . been spontaneously reborn, and will gain Nibbāna from that state without returning to this world’ (L 240). This indicates that significant progress towards enlightenment is possible in this lifetime for those who do not enter the Sangha. The Buddha presented the Eightfold Path as a middle way between the extreme asceticism of the samaṇ as and the worldly lives of most people. Yet life in the Sangha is likely to look quite ascetic to most people. However, to revert to the earlier metaphor, perhaps the middle way is not an express track to which local tracks are mere means of eventual access, but a wide multilane highway in which some lanes are relatively withdrawn from the affairs of the world while others are more integrated with them via a network of connecting roads. Maybe, as indeed some Buddhists believe, it is possible to attain, or at least significantly progress towards, enlightenment not by literally withdrawing from the everyday world and forming an alternative community, but by changing that world from within.

The life of the Buddha does not provide us with a model of such integration. But if the teaching of the Buddha is to have value for all persons here and now, we need to see if the middle way is wide enough to make the search for enlightenment relevant to the kinds of lives most of us live. The Buddha did not emphasize this possibility, but that does not necessarily mean we should not emphasize it. We live in a very different world from that of the Buddha. The key to this possibility is the extent to which the everyday lives of work and family that most persons lead could be transformed into a meaningful search for enlightenment, and the degree to which such lives could be informed by the ideal of non-attachment.

SUGGESTED READING

Suggested reading in the suttas is usually indicated by title, work in the Sutta Piṭaka, and number of the sutta (#). On the life of the Buddha, see the Ariyapariyesanā Sutta (‘The Noble Search’), M #26. See also the Bhayabherava Sutta (‘Fear and Dread’), M #4, the Mahāsaccaka Sutta (‘The Greater Discourse to Saccaka’), M #36, and the Mahāpadāna Sutta (‘The Great Discourse on the Lineage’), L #14. The end of the Buddha’s life is depicted in the MahāpariNibbāna Sutta (‘The Great Passing: The Buddha’s Last Days’), L #16.

For brief accounts of the Buddha’s life and teaching, see Armstrong (2001) and especially Carrithers (1983). More detailed accounts can be found in Nakamura (2000) and Ñāṇamoli (2001). For background on the Indian philosophical traditions from which the Buddha emerged, see Hamilton (2001) and R. King (1999).

THE TEACHING IN BRIEF