SACRED MOUNTAINS AND TALKING DRUMS The Tibetan Chöd Practice

By Verónica Rivas

“No gods, no demons, no buddhas and beings, No self, no objects, no harmers, nothing to be harmed.”1

In some dank mountain, where you are exposed to external dangers that can end your life without warning... the sound of a drum and a rhythmic melody can

bring out the weaknesses that you did not know and your deepest fears. The dance of life and death, in a constant dialogue, appear in a calm and threatening way. There are no differences in status, no fame or prestige. We are alone and everything that we were, we are, and we will be is present at

the same moment. And impermanence, from which we constantly try to flee, comes in the form of a deity or a devil... or both. Suddenly, impermanence is transformed into a strong invocation that is rooted in the entrails, which is externalized disintegrating everything that was our truth and where the

spirit truly nourishes, rejoices, and takes control. We become part of the death that happens again and again in a tedious and constant cycle. And from the darkest moment, from some deep place: a clarity. The words above do not exactly define a Chöd practice, but they do describe, in a general way, an

experience that could result from its practice. As we will see, for many, the focus of Chöd rituals is enlightenment, but for others it is a way of dealing with different spiritual realities as well as the spirits of the dead. Superficially we could say that both purposes are irreconcilable, but, if we investigate the origins of Chöd's practice as well as the philosophical conception that impregnates it, we will see that Chöd in its own essence

contains these two purposes and much more. During my research for this article, I found myself reading several academic works and articles on the subject as well as sadhanas (liturgies), and I must confess that for several days I found myself lost among all of it. Most of the material available on this subject is of Buddhist origin and this, in a certain way, constitutes a problem to be addressed, because if we were limited to this material we would be considering

just only one aspect or interpretation of what constitute a Chöd ritual. So, my task was to focus on finding other sources, other visions. When I found them they were very few and not very deep, but even so they gave me elements that I could try to read between the lines, about the possibility of the existence of the practice outside the Buddhist or the Bön-po2 conceptions.

Troma Sadhana. Translated by Sarah Harding

We will talk briefly about Bon-po later

All the discussions about the Chöd practice have as a starting point its geographical origin and the development of its lineage. In fact, these elements are essential to define what is a Chöd ritual and its purpose. From my point of view, the practice of Chöd is a powerful technique of meditation and trance,

composed of several elements that could be considered shamanic and whose purpose is to cause a transformation in the reactive quality of the mind. That purpose is achieved through a kind of journey to other realities that coexist with us and where all kinds of spiritual entities, including the spirits of the deceased, are fed with our own body.

Origins

The word Chöd, or Gcod, means "cutting through", but also means "to serve". According to this, we see that it covers the two basic effects that describe the ritual. The researcher Janet Gyatso, in her excellent work "The Development of the Gcod Tradition" talks about the intrinsic shamanic elements of the

practice but, at the same time, warns that one cannot underestimate the great importance that the Buddhist doctrines, especially the Mahayana3 and Vajrayana4 doctrines, had in the development and evolution of the practice. Until now, almost all scholars believe that the Buddhist Chöd practice originated in India. The practice of Chöd introduces itself as a very old method that went through an important evolution throughout its history, which made

it adapts to different times, cultures, and ways of living, constituting in the process an uninterrupted lineage up to nowadays. It is also important to consider here that this evolution is in a certain way guided and marked by a strong feminine presence, which begins with the pro-eminent figure of Machig Labdron, about whom we will talk about later. When we look for sources to trace the origin and the roots of the practice of Chöd, we find the problem of

whether it is a practice essentially derived from the sutras, from the tantras, or from both. Also there are the questions about if Chöd is an eminently Buddhist practice, if it is strongly influenced by Bön-po doctrines or, maybe, if it is an essentially shamanic practice. The oldest source that places the practice of Chöd in Hindu lands is a poem composed by Aryadeva the Brahmin5 called The Grand Poem,

3 Mahayana means “great vehicle

It is a branch of Buddhism. The Mahayana tradition emphasizes that any can aspire to achieve awakening and become a bodhisattva (someone that wishes to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings). Non-Mayahana teachings believe that only the Buddha can be called a bodhisattva. According to the Mahayana, awakening means to understand the true nature of reality. Among the most important texts of the Mahayana tradition we find the Prajnaparamita Sutra and the Lotus Sutra.

4 Vajrayana means “thunderbolt vehicle” or “diamond vehicle” and it is a form of Tantric Buddhism. It seems to have flourished between the 6th and the 11th century. It is also known as Mantrayana because of the importance of the use of mantras to prevent the mind from following the illusory display of dualistic reality.

5 According to the scholar Janet Gyatso, Aryadeva the Brahmin was Pa Dampa Sangye´s uncle and not the famous philosopher and thinker knowns as Aryadeva. which seems to be a consistent proof that by the tenth century this ritual was already a well-established practice in India. It seems that this Chöd practice was taken to Tibetan lands by Pa Dampa Samgye6. Dampa called his method "The Pacification of Suffering" and it constitutes the so-called "way of the Sutras". According to Jerome Edou, Dampa transmitted it to Sonam Lama7 and it seems that the latter would be the one who would have finally passed it

to Machig Labdron. On this topic there are discrepancies between the experts since Labdron’s texts feed those doubts. But who was Machig Labdron and why is she considered as the great systematizing of Chöd practice? Machig was born in Tibet and lived between the last half of the 11th century and the

first half of the 12th century. In her biography we find elements that often lead us to ask if we are talking about a woman or a deity. Machig, because of her practice, realization and her inheritance is currently considered a Dakini8. Curiously, she was not the consort of a Lama or an important spiritual master, she was neither a nun nor a hermit, but she was a common woman, a mother, in who arose an enormous desire to dedicate herself to spiritual practices for the liberation of all sentient beings. In some stories, where Machig appears in a more deified way, we can read elements that match her

story with that of Tara9. It is said that Tara was a princess completely dedicated to her spiritual practices demonstrating great progress. Because of this, some monks recommended her to use the siddhis (accomplishments) that she had achieved as well as her merit to achieve a rebirth in a man's body to

reach enlightenment. To this Tara replied that there was no intrinsic reality in the body of a man or a woman, that it was only ignorant minds who insisted

on that, and for this reason, she made the vow to return one and countless times in the body of a woman, as a bodhisatva until there was no being subject

to samsaric suffering10. In a similar way, they say that Machig was in his previous life a male practitioner who vowed to return in a female body to give a new perspective to the Chöd practice. What we really know is that Machig, at some point, left the life she had as a woman who took care of her family and began to travel to different places, to practice in

6 Pa Dampa Sangye was a great yogi, considered a mahasiddha (somebody who embodied great perfection) who was born in India and transmitted in Tibet many teachings based on the Tantras and Sutra, approximately in the 11th century. 7 Kyoton Sonam Lama was, according to Judith Simmer-Brown, a wandering yogi

of great realization. He seems to have lived in the 12th century. 8 Dakini, in Tibetan Mkha’gro’ma, in Japanese Buddhism Dakiniten; they are spirits who represents primordial wisdom who have a very important role in the Tantric Buddhism. There are many categories of dakinis, but we can distinguish among the

fully enlightened dakini and the worldly dakini. They are of wrathful or peaceful appearances. It is also considered that a woman of great knowledge, that has achieved in her life great accomplishments, or who is an inspiration for other practitioners, can be considered a dakini, 9 Tara is a protective and savior goddess. She was introduced in the Buddhist pantheon and she is worshiped as the “great savior” who dissipates all fears and cleans the obstacles on

the path to enlightenment. She assumed several aspects and many sadhanas (liturgies) praise to what they called “The 21 Taras”. 10 According to Buddhist teachings, the term “samsaric suffering” refers to the endless cycles of death and rebirth. caverns and inhospitable places. She received initiations from several teachers and in several lines. It seems that she also knew some Bön-Po practices

very well because of her family origin. So, we have that the lineages of the Chöd practice can be grouped into three categories: the lineages of the Sutra, those of Tantra and those who combine Sutra and Tantra. The Chöd system taught and disseminated by Machig combines the lineage of the tantra together with the Prajnaparamita Sutras11 and the cultivation of the Six Paramitas which are: Dana Paramita (generosity), Sila Paramita (virtue, proper conduct,

discipline); Ksanti Paramita (patiente, tolerance, endurance); Vyria Paramita (diligence, effort); Dhyana Paramita (concentration, contemplation, Prajna Paramita (wisdom). Thus Machig systematized the practice of Chöd, being the initiator of a lineage that it is well known today, which combines the teachings of the Sutras and Tantras and is called "Mahamudra Chöd." Some scholars believe that the lineages of the Tantra also derive from Machig and

correspond to some teachings she gave to some adepts. The lineage of the Sutra derives from Pa Dampa Samgye. Considering this we can ask ourselves if the Chöd practice refers only to its Hindu origins or if it also existed among the Bön-Po. Before dealing with this issue it is important to mention that when we refer to Bön-Po, we are not thinking of a unified and homogeneous movement, but instead, we can distinguish phases, which probably coexist

simultaneously until the present. So we have the Primitive Bön which comprises the folk traditions of Tibet and which some authors call "the nameless religion". Then we have the Yungdrung or Eternal Bön, which was founded by the Buddha Tonpa Shenrab12. This line shares many similarities with Buddhism but its followers strive to show that it is something completely separate and different from Buddhism. And finally we have the new Bön, which appears

approximately between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and which is a kind of amalgam between the Yungdrung and the Nyigma School, which is the oldest tradition of Tibetan Buddhism; its followers say that it was founded by Padmasambhava13. Many of the sources I consulted, especially the researcher Alejandro Chaoul, affirm that Bön-po had a strong and ingrained tradition of Chöd practice and that they were used to it. For them the practices of Chöd

are divided into three groups, namely: Peaceful Chöd, Extending Chöd and Powerful Chöd; and the new Bön adds to them the so-called Wrathful Chöd. Many sadhanas of Chöd already existed in the Bön tradition and the same Chaoul says that, by the fourteenth century, the sadhana known as Chöd of the Skygoers, one of the most popular Chöd sadhanas, was very well known among the Bön-pos. While there are several practical ritual texts and liturgies of Chöd among the

11 Prajnaparamita means “perfection of wisdom”, but the word also refers to a particular body of Sutras (teachings or religious discourse, they could be written in an aphorism style and they can be long or short; they take part of the doctrinal corpus of Hinduism, Buddhism, etc). According to the scholar

Edward Conze the erliest sutras are Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita and Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita. 12 Tonpa Shenrab, also known as Guru Shenrab. According to Iñaki Preciado, Tonpa means “great master” and Shenrab, “supreme shaman”. He is the founder of the Yungdrung Bön. 13 Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, Padma Jugne, “The Lotus Born”, was a great magician, yogi and tantric practitioner. He introduced the Tantric Buddhism in Tibet. He was a great mystic and philosopher.

Bön-po tradition, it seems that the source of these rituals would be the Mother Tantra14, which is considered as the source of the first three Chöd groups mentioned above. Regarding to what was said above, we quote Gyatso who states:

Finally, the Bön-po have a number of Gcod cycles which seem to stem largely from visionary transmission, and which have been classified into four types corresponding to the four tantric activities: peaceful, extending, powerful, and wrathful.15

Chöd as a shamanic necromantic practice

Among various traditions, mountains are considered to be the dwelling of hostile spirits, and are also related to death. For example, the Mayan and the Nahuatl, - two of the most important cultures that flourished in the Mesoamerican land -, considered mountains to be the abode of the gods of the

Underworld and their messengers. In several rituals, when the priests wanted to invoke their ancestors, they used to cover their bodies with a kind of black ointment made of a mixture of herbs, ashes and animal blood. The ritual could be performed in temples or in places of difficult access like mountains or forests and they bled their own bodies in specific places (especially in the sexual organs or the tongue) as an offering to the spirits that lived

there, as well as to feed their own ancestors. Along with this they used songs and invocations. In Tibet, mountains were linked with death as well and they were considered the dwelling of wrathful spirits. At certain times, it was the custom to carry the bodies of people who died and left them in the mountains, where certain birds and animals fed. Concerning this it would be interesting to add that the dakinis, - who were considered female flesh-eaters

and blood drinkers demons at the service of Kali16 -, were to be found in mountainous places where there were bodies in all states of decomposition. When these spirits were incorporated into Buddhist practices, especially in the Tantric Buddhism, they began to have the function of being manifestations of primordial wisdom, the guides of practitioners and the ones responsible for giving the most important initiations. But, if we look closely at their

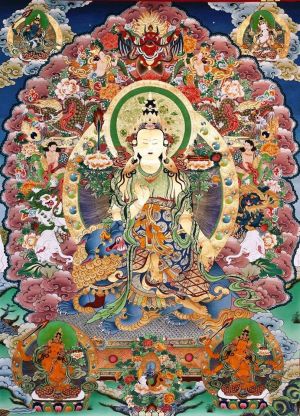

iconography and representation, we will see that they did not lose their previous characteristics and ferocity, the difference being that now all this is directed to a different purpose: enlightenment. The practice of Chöd is chaired by the Dakini Troma Nagmo. Troma Nagmo is represented and visualized with her body in black or in a very dark blue, with an angry and ferocious aspect and standing in a dancing position over a corpse. Some sources consider her the Tibetan syncretization of the goddess Kali.

Mother Tantra is a compound of various tantras also called the Yogini Tantra

They focus on the idea that the enlightened mind can be achieved through the cultivation of a pure mind, and that desire is also a path to enlightenment. So, the tantric practitioner should cultivate devotion in his daily practice. All life circumstances could be transformed into a

source of devotion. 15 Gyatso, Janet. Soundings in Tibetan Civilization. "The Development of the Gcod Tradition", pp, 340. 16 Kali is a Hindu goddess. She embodies the principle of destruction but also of generation. Over time she started to be conceived as Mother Goddess, but she never lost her previous attributes. She is worshiped by lots of tantric practitioners.

Thus, Chöd was traditionally practiced in charnel grounds or cremation places, in mountains and places of difficult access or in the middle of the forests and, according to Alexandra David-Neel17, also in haunted places linked to tragic stories that had happened recently. The reason for this was the energy of

the spirits and all types of beings that inhabit there. In these places, the practitioner (Chöd-pa) finds himself in the middle of everything that may disturb and terrified him. He faces the visible effects of impermanence: decadence and death. But also, through this ritual, he can perceive life in all its extension and the impermanence of death itself. Namkhai Norbu describes the Chöd practitioners as follows:

Practitioners of Chöd are traditionally nomadic, travelling continually from place to place with a minimum of possesions, as medicants, often carrying nothing more than the ritual instruments of a damaru or two-sided drum, a bell and a thigh Böne trumpet, and living in a small tent set up using a ritual

trident (katvanga) as its tent pole, and four ritual daggers (phurba) as its tent pegs. The practice is principally undertaken in lonely and desolate places, such as caves and mountain peaks, but particularly in graveyards and charnel grounds at night, when the terrifying energy of such places, serves to

intensify the sensations of the practitioner who, seated alone in the dark, summons all those to whom he owes a karmic debt to come and receive payment in the form of the offering of his body. Among the invited are Buddhas and illuminated beings, for whom the practitioner mentally transforms the offering into

nectar, and all the beings of the six states of conditioned cyclic existence (samsara), for whom the offering is multiplied and transformed into whatever will be of most benefit and most pleasing, but also summoned are demons and evil spirits to whom the body itself is offered as a feast just as it is.18

As we see, according to Namkhai Norbu, the practice of Chöd was performed by people of wandering lifestyle, by yogis, mystics and travelers. The same Dampa Sangye and Machig Labdron were no exceptions. They never were attached to a place and they established a lineage, but never a school. But progressively,

the practice of Chöd was confined to the monasteries, usually practiced by lamas who do not look kindly on those errant hermits or those who work with spirits and use these rituals to perform exorcisms or to communicate with the spirits of the dead. It would be interesting to read the description that Alexandra David-Neel, as she was one of the first chroniclers and was fascinated by the Magic of the Tibetan mountains, gave about the practice of Chöd:

The reason of this preference is that the effect of chöd, or kindred rites, does not depend solely on the feelings aroused in the mind of the celebrant by the stern words of the liturgy, nor upon the awe-inspiring surroundings. It is

Alexandra David-Neel (1868-1969)

She was an explorer and spiritualist born in France. 18 Norbu, Chogyal Namkhai. The Cristal and the Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen, pp, 5152.

also designed to stir up the occult forces, or the conscious beings which – according to Tibetans – may exist in such places, having been enervated either by actual deeds or by the concentration of many people's thoughts on imaginary events.19

It is interesting to consider David-Neel's appreciation, not only for the elements she describes but also because it is the observation of a Western explorer in a time when it was very difficult that Tibetan people allowed a foreign to witness their rituals and customs. She strongly points out that apparently this ritual not only causes effects in those who practice it, but also in the environment because the energies present in the places find a way of manifestation. On the other hand, the scholar Giussepe Tucci concentrates on describing the elements necessary for a Chöd practice:

The following implements are required for the performance of these rituals: a trumpet made of a human tibia (rkang gling), which renders lha and ’dre submissive; a damaru (the shaman’s drum); a small bell; hair woven into a tuft and a piece of Persian cloth (stag gzig gi ras ma), human skin or skin of a wild animal with the claws intact: this serves to subdue the demons (dregs).20

In some rituals the phurba (ritualistic dagger) is also used for directing energy or subjugating. We see that the elements used in the ritual are basically those capable of producing a certain specific type of sound, since it is said that the sound of the bell and of the damaru for example, can reach and

penetrate all realms. They also have a function of invocation, guidance and prayer at the same time. We also observed that not only it is enough to perform the ritual in a place that in some way has a link with death, but also many of the ritual instruments represent death for themselves. In a certain way, if we were not in a place linked to the deceased, the presence of these instruments would already be enough for the ritual to be effective. Next, this same

author describes the phases that take place in the ritual. The first phase is called "White sharing". In this phase, the physical body of the practitioner is conceived as transformed into nectar that is offered to the so-called "Three Jewels" (Buddha, Dharma and Sanga). The next phase is called "multi-colored

sharing", here the body is transformed into elements such as food, clothes, jewelry or all kinds of objects that are desirable to the so-called Protectors 21. Then there is a third phase called "red sharing". Here the flesh and blood of the practitioner are conceived as dispersing through space to serve as food for demonic beings of all kinds. Thus, after this stage is over, the next is known as "black sharing". In this phase we imagine that all our faults, everything that is considered wrong or an

19 David-Neel, Alexandra. Magic and Mystery in Tibet, pp, 92. 20 Tucci, Giuseppe. The Religions of Tibet, pp, 91-92. 21 The Protectors are spirits, most of them of wrathful appearance that guard the practitioner during a ritual or in daily life. Among Tibetan beliefs there are protectors of the four directions, of the Elements and every natural place has a protector spirit. All of them should to be greeted or served to assure the well performance of a ritual.

obstacle to enlightenment and that of all beings, are absorbed by our own body and thus, our body is offered to all those beings that are passing through intense suffering and to fully enlightened beings.22 It is important to clarify here that Tucci is basically describing the ritual of the lineages founded by Machig Labdron, which is the Buddhist Chöd. But when we refer that the practice of Chöd is directed to make a kind of cut, we are referring to a cut or

break with what? It is breaking with the influence of the Four Maras. These Four Maras are called: Substantial Mara, Insubstantial Mara, Mara of Intoxicating Joy and the Mara which is the root of three Maras mentioned before, known as the Mara of Grasping to the Self. These Four Maras are what Machig Labdron refers to when she talks about the Four Demons. For her, a demon is everything that could mean an obstacle in our spiritual path. So, not

only terrifying circumstances could be demons, but also a friend, says Machig, can become one in certain circumstances. The existence of these demons, according to her, depends exclusively on how our mind experiences and understands them. Whenever our mind is only reacting to the circumstances, facing the environment with attachment or aversion, we will be in a situation in which we want to hold on to what we like or we are constantly running away from what

we do not want. In both cases the resulting feeling is fear and we are constantly creating different kinds of demons. So, says Labdron, these demons take shape in our daily lives through diseases, unpleasant events, depression, and anxiety, among others. Then we can say that the practice of Chöd is directed to "cut" with the reactive habit of our mind. The Substantial Mara refers to how we perceive and how we relate to external objects. It is our cognitive

perception. When we perceive an object for example, we immediately have an experience of pleasure or rejection. Whether we experience pleasure or affliction this makes us link to the emotions that result from the experience. On the other hand, the insubstantial Mara occurs independently of the presence or absence of a given external condition. It does not refer to a reaction we have to something, but refers to the so-called kleshas (attachment,

aversion, bewilderment, pride and jealously). They arise in the mind spontaneously and they are always present, latent, to a greater or lesser extent. From these kleshas come the accumulation of karma23 and they are therefore the source of all suffering. But on the other hand, if we live a relaxed life, feeling that we have absolutely everything, having the illusion that nothing can be better, or if as spiritual practitioners we achieve siddhis as

clairvoyance, for example, or a high recognition for what we do, and we stay fixed in that, we will not have a true inspiration for continuing our practice, and we will have the illusion that we have already achieved everything. Those things are just proving that our practices are giving results, but we are probably far of attaining the supreme siddhi (enlightenment or the Vajra state of mind). This mara is called the Mara of Intoxicating Joy. Here the

problem is not that we have fame or wealth and a life full of pleasures, but in the way our mind perceives and experiences them. Finally, the 22 Ibidem. 23 Karma is the principle of cause and effect. It means “action”. Good or bad actions determine the existential condition of one´s life. It is a key concept in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, among others.

Mara of Grasping is presented in these teachings as the root of the three previous maras. When we cling to our own being, to our own experience of life, we link to experiences such as abilities that we possess, or a certain physical aspect or a way of being and we live only devoted to this, we are generating a great source of suffering since we will irretrievably lose all this. Now, let’s pay attention to the Chöd definition that follows:

Chöd is a practice that combines Buddhist meditation with ancient TibetoSiberian shamanic ritual. The "liturgy" of Chöd is sung to the accompaniment of drum, bell and a thigh-Böne horn.24

This definition basically mentions all the elements that we have been talking about until now, but it adds something important: the fact that Chöd is a practice that combines Buddhist elements with Tibeto-Siberian shamanic rituals. In a certain way and as we saw, this definition would leave out the Chöd practices of Bön-po, since until now there is no clear evidence of a cross between Bön-po and Buddhist techniques regarding the Chöd rituals. But what

interests us in this definition is the shamanic component mentioned and it would be interesting to make an observation: we are not referring to whether Chöd practitioners are shamans, or if it was shamans who created the practice of Chöd, we are referring whether or not the Chöd practice is a shamanic

experience. On this subject, if we have in mind what the anthropologist Brian Morris says about: "the shaman is seen as existing in two worlds: in the ordinary world of daily life and in the hidden world of the spirits into which he or she enters during a trance state. "25, - we can consider that Chöd is

an essentially shamanic and necromantic experience. He then clarifies that these two worlds or "two realities" are the material reality, which would be our experience of material and physical life, and the spiritual reality, which would be where spirits dwells, the souls of the dead as well as other beings and deities. Morris says that a shamanic ritual includes singing, drumming, visionary experiences and activities that induce ecstasy. But he quickly points

out that the use of psychedelic plants or substances is not a determining factor in a shamanic ritual and may or may not be present. Although the fact of reaching an altered state of consciousness would be a determining factor for a shamanic experience, these do not depend exclusively on psychedelic substances. In this way, circumstances such as isolation in remote places such as mountains or forests, fasting, a frantic dance, even the presence of

external elements that intensify the feelings of the practitioner or certain meditative states can lead to deep trance states26. To conclude, as we have seen, the practice of Chöd has undergone an important evolution from its origins until today. We should strip ourselves of the reductionist approach of thinking that the authentic practice of Chöd is that performed by the initiates in a monastery or a temple, without considering the solitary practitioner. It is

24 Dharma Fellowship. Member Essay: “Chöd: An Advanced Type of Shamanism”, pp, 1. 25 Morris, Brian. Religion and Anthropology. A Critical Introduction, pp, 18. 26 Ibidem.

also an error to believe that having enlightenment as our goal must be opposed to the animistic or to the shamanic interpretation of the reality and of our spiritual path. The practice of Chöd, whether of Buddhist origins or of Bön influence, is the result of the experiences and dedication of hermits, yogis,

mystics and monks. It was used to appease the spirits of nature, the fury of the elements, family misfortunes, to revere and serve the dead, to obtain guidance and advice, for protection and many other reasons. For all this, its purpose cannot be other than the full understanding of what is the truly essence of the mind. If we affirm with the scholars Mageo and Howard that: "When the change radically alters to society's formal structures, traditional

gods may disappear or take on spirit like attributes, while spirits linger and reflect the changing qualities of personal experience”27, we can say that the practice of Chöd reflects, not only in its history, but also in its components the social and cultural evolution of all the aspects that compose it.

The tantric point of view basically expresses that all circumstances are sources or ways to obtain enlightenment, thus, it is the tantric element which makes the practice of Chöd so permeable and able to fit almost all needs and situations. In the play of the damaru of whom today is engaged in the practice of meditation for the purpose of obtaining self-liberation and the liberation for all sentient-beings, there is also the play of the ancient hermit for whom the dead were not dead and who offered his body for the benefit of the departed spirit and for their transcendence.