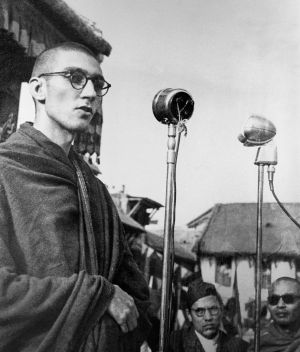

The Life of Urgyen Sangharakshita

1925 - 2018

As with any life story, Sangharakshita's could be told in many ways, from many different perspectives.

Here, we've attempted to give a flavour of the key moments in his life through excerpts from a variety of media. As far as possible we've drawn on his own written and spoken words, as well as video clips and photos – primarily from the Triratna Picture Library.

We hope you enjoy these glimpses into Sangharakshita's rich legacy and are inspired to discover more by following the links to the sources.

Compiled by Suryanaga and Prajnaketu, with input from Mahamati and Kalyanaprabha.

“Apart from my refusal to cry when born, the strangest circumstance of my most recent appearance in this world on 26 August 1925 is that it took place in a nursing home in south-west London only a few hundred yards from the spot where, two years earlier, had died Allan Bennett, otherwise Ananda Maitreya, the first Englishman to take the yellow robe in the East and return to teach the Dharma in his native land.”

- The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, p.480)

Dennis was born into a working-class family in South London, in the time between World Wars

His father was a furniture polisher, his mother had been a waitress, and he had a younger sister, Joan

“I am by nature conservative. I have always loved what is old, whether old churches, old books, or old manners and customs.

Being conservative, I do not welcome change, especially sudden change, which tends to make me socially and politically a gradualist. As befits a conservative, I am a collector of what used to be called curios and are now called collectibles. As a boy I collected cigarette cards, postage stamps, and old coins...”

- A Complex Personality: A Note (CW26, p. 639)

Aged eight, he was misdiagnosed with a heart condition and confined to bed

“I have more than once reflected that the two years I spent confined to bed, alone with a few books and the Children’s Encyclopaedia, must have had a decisive influence on my character and thus on the course of my whole life thereafter.

Until then, so far as I know, I had been just an ordinary boy, indistinguishable from other working-class Tooting boys. Like them I loved playing in the street, was not particularly fond of school, got into scrapes (and fights), and was overjoyed when I could go fishing with my father on a Saturday afternoon. The discovery that I had heart disease put a stop to all that.”

- Moving Against the Stream (CW23, pp.8-9)

“As soon as I was free from invalidism and able to borrow books from public libraries, I started developing some of the interests I had formed in a more specialized way. …

I wasn't content with reading just one or two books: I wanted to study a whole lot – and that's how I have come to collect quite a few books about, for instance, Milton, Blake, D. H. Lawrence, John Middleton Murry, and the ancient Greek philosophers, especially Plato and Plotinus.”

Conversations with Bhante

Aged fifteen, he realised he was not a Christian

“How shall I describe [[[Isis]] Unveiled's] effect on me? Though in itself almost entirely negative, it proved to be more far-reaching in consequences than any book I had previously encountered. Within a fortnight I had read both volumes twice from cover to cover.

Impressed, bewildered, thrilled, excited, stimulated as I was by their staggeringly immense wealth … on every conceivable aspect of philosophy, comparative religion, occultism, mysticism, science, and a hundred other subjects, the realization which dawned most clearly upon me, and which by the time I had finished stood out with blinding obviousness in the very forefront of my consciousness, was the fact that I was not a Christian – that I never had been, and never would be.”

- The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, pp.63-4)

A year later, he discovered the Diamond Sūtra in a London bookshop

“At the age of sixteen I had my first real contact with Buddhism. That contact took place when I read two short but exceptionally profound Buddhist scriptures of great historical and spiritual significance.

These were the Diamond Sūtra, a work belonging to the ‘Perfection of Wisdom’ corpus, and the Sūtra of Wei Lang, a collection of discourses by the first Chinese patriarch of the Chan or Zen school, who is better known as Huineng. Reading these two works and realizing that, although in one sense the truth they taught, or the reality they disclosed, was new to me, in another sense it was not new at all but strangely familiar. I certainly did not feel that I was accepting an Eastern religion, or a religion that was foreign and exotic. Rather I felt that contact with Buddhism was, at the same time, contact with the depths of my own being: that in knowing Buddhism I was knowing myself, and that in knowing myself I was knowing Buddhism.”

- The Priceless Jewel (CW16, pp.217-18)

Sent to India during World War II

Stationed in India, Dennis read more about Buddhism (and Hinduism) and started to meditate

“At night, seated cross-legged inside the mosquito curtain while the other inmates of the room slept, I practised according to the instructions given in the book. [Aparokṣānubhūti by Shankara] ‘I am not the body, I am not the mind,’ I reflected, ‘I am the non-dual Reality, the Brahman; I am the Absolute Existence-Knowledge-Bliss.’

As I practised, body-consciousness faded away and my whole being was permeated by a great peaceful joy. One night there appeared before me, as it were suspended in mid-air, the head of an old man. He had a grey stubble on scalp and chin and his yellowish face was deeply lined and wrinkled as though by the sins and vices of a lifetime. ‘You’re wasting your time,’ he exclaimed with a dreadful sneer. ‘There’s nothing in the universe but matter. Nothing but matter.’

‘There is something higher than matter,’ I promptly retorted, ‘I know it, because I am experiencing it now.’

Whereupon the apparition vanished. Years later, during my second visit to Nepal, I saw the same Māra, as it must have been. I recognized him at once, and he no doubt recognized me.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, pp.113-14)

Looking for spiritual teachers, Dennis found the Hindu Ramakrishna Mission and began to feel drawn to a devoted spiritual life

“Years later, when my enthusiasm for the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda literature had waned, I was to wonder why they had attracted me so powerfully.

Perhaps it was because they demonstrated that the spiritual life, far from being practicable only in the remote past, could be, and in fact had been, lived in modern times – perhaps because they indirectly encouraged me not merely to study but actually to practise the teaching to which I was already committed, the teaching of the Buddha.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, p.117)

“During that period the signals unit to which I belonged had been ordered overseas, I had been stationed in Delhi, Colombo, Calcutta, and Singapore, had made contact with Chinese and Sinhalese Buddhists, had returned to India (for good, as I then thought), had been associated with various religious organizations and groups, both Buddhist and Hindu, and had taken up the regular practice of meditation. …

“Together with the Bengali friend with whom, on my return to India, I had joined forces, I had worked for the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture and for the Maha Bodhi Society. More recently, I had been involved in a project for the revival of the Dharma Vijaya Vahini, an organization for the propagation of Buddhism in India… .

With all these organizations, as well as with the group that had formed round a well-known female ascetic [Andanamayi], I had been deeply disappointed, as had my friend. Working with such bodies was, it seemed, a hindrance rather than a help to spiritual development.”

– The History of My Going for Refuge (CW2, pp.412-13)

When the War was over, Dennis was due to return to the UK.

Faced with the choice of going home or continuing his spiritual life in India, he deserted the army, burned his passport, and donned the robes of an ascetic

“For the last few months we had only sat hesitantly on the shore of the vast ocean of the spiritual life. Now, casting aside all fear, we would plunge boldly in.

Having made this resolution, we lost no time putting it into effect. With the help of a handful of gerua-mati, the reddish-brown earth used since time immemorial by Indian ascetics, we dyed our shirts and sarongs the traditional saffron of the world-renunciant. Suitcases and watches were sold, trousers, jackets, and shoes given away, identification papers destroyed. Apart from the robes that we were to wear we kept only a blanket each and our books and notebooks. …

Tibetan Buddhists believe that the appearance of a rainbow is one of the most auspicious of signs, and the biographies of their saints and yogis are replete with references to this phenomenon. Whether our ‘going forth’ on 18 August 1947 may be considered an auspicious event I cannot say, but it was certainly signalized by the appearance not of one but of scores of rainbows.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, pp.225-6)

He began to look for a Buddhist community to support his spiritual aspirations

“Thus the rainbow became for me a symbol of the spiritual path, the track of which I have followed, in one way or another, all my life.”

– Rainbows in the Sky (CW26, p.672)

Two years as a homeless wanderer in India

Dennis adopted the name ‘Dharmapriya’ and – along with his friend Satyapriya –resolved to wander the length of India in the fashion of the Buddha

“For the first hour the going was pleasant enough. But as the sun ascended we began to feel hot and tired. Our bundles, so small and light to the eye that morning, felt heavy as lead, and for the first time in my life I wished that I possessed fewer books. When my arm started aching, I slung the bundle over my shoulder, and when the heavy bamboo began chafing my collar bone I transferred the ever weightier bundle now to my right hand, now to my left. As, with each change of position, my arm started aching, and my collar bone paining me more quickly than before, I was soon shifting the bundle every few minutes. Meanwhile, my feet had blistered and I started to limp. Satyapriya, though stronger and sturdier than I, was also feeling the strain. In this sorry state we entered our first village.

It had been our intention to allow ourselves a short rest, but as we plodded wearily past the single row of mean huts, the inhabitants, who from their dress we recognized as Muslims, shouted and jeered at us with such obvious ill-nature that we did not stop.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, p.243-4)

But finding the homeless life unhelpful for meditation, they settled in an ashram in Muvattupuzha

After fifteen months there, they felt they had settled long enough and returned to the homeless life, staying in other ashrams and caves

Staying in a cave near Tiruvannamalai, he had an important vision

“One night I found myself, as it were, out of the body and in the presence of Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, who presides over the western quarter of the universe. The colour of the Buddha was a deep, rich, luminous red, like that of rubies, though at the same time soft and glowing, like the light of the setting sun. While his left hand rested on his lap, the fingers of his right hand held up by the stalk a single red lotus in full bloom and he sat, in the usual cross-legged posture, on an enormous red lotus that floated on the surface of the sea. To the left, immediately beneath the raised right arm of the Buddha, was the red hemisphere of the setting sun, its reflection glittering golden across the waters. How long the experience lasted I do not know, for I seemed to be out of time as well as out of the body, but I saw the Buddha as clearly as I had ever seen anything under the ordinary circumstances of my life, indeed far more clearly and vividly. The rich red colour of Amitābha himself, as well as of the two lotuses, and the setting sun, made a particularly deep impression on me. It was more wonderful, more appealing, than any earthly red: it was like red light, but so soft and, at the same time, so vivid, as to be altogether without parallel.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, p.345)

He felt this vision was a sign it was time to end their homeless wandering and seek their next step: Ordination as Theravādin monks

At the Maha Bodhi Society in Varanasi (northern India), their request was harshly rejected

But then, a local monk-scholar, Jagdish Kashyap, told them about someone in Kusinara who might ordain them

“Having listened in sympathetic silence, Bhikkhu Kashyap pondered deeply for a while.

Then, rolling the words up from the depths of his enormous frame with a slowness that gave them a special emphasis, and speaking with evident warmth and sincerity, he advised us to go to Kusinara, the place where the Buddha had passed away into final Nirvāṇa. There we would find U Chandramani Mahāthera, the seniormost Theravādin Buddhist monk in India. He had many disciples. In fact, he was well known for the generosity with which he gave ordinations. Provided we were able to convince him of our sincerity, there was no reason why he should not give us ordination too.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, p.395)

They walked a further 211 kilometres (131 miles) from Varanasi to Kusinara in blistering heat

Then, on 12 May 1949, they were finally ordained as śrāmaṇeras (novice monks) and given new names – Sangharakshita and Buddharakshita.

“While U Chandramani was much concerned that I should pronounce the words of the Refuge-going formula with perfect correctness, both in Pāli and in Sanskrit, and took a great deal of trouble to ensure this, he had absolutely nothing to say about the meaning of those words or about the significance of the act of Going for Refuge itself, so that in one respect, at least, I was no wiser after my śrāmaṇera ordination than I had been after taking pansil from U Thittila.

[However,] I felt delighted, thrilled, exhilarated, and inspired, as well as intensely grateful for all the kindness I had received at the hands of U Chandramani and his little band of followers. Like my taking pansil and my Going Forth, my śrāmaṇera ordination was not just part of a process but was of value and significance on its own account.”

– The History of My Going for Refuge (CW2, p.419)

Ordained as a Theravādin monk

After their śrāmaṇera (junior monk) ordination, Sangharakshita and Buddharakshita begged for almsfood in the traditional manner

“Our main preoccupation next morning was to find a place where we could start putting our begging-bowls to the use for which they were intended and go for alms. Now that we were śrāmaṇeras we were resolved to do this in strictly traditional fashion. We would beg from door to door until we had obtained enough cooked food for our one meal of the day, not skipping so much as a single house. We would not accept people’s invitations, nor would we even sit down inside a house in order to eat the food that we had collected.

After walking from 5.30 until 10.30, with only a little chatua to sustain us on the way, we were feeling rather hungry. But at the first township to which we came we found the atmosphere so forbiddingly commercial that our courage failed us and tired as we were we decided not to stop there. Luckily there was a village only a mile further on. Before reaching the village proper, which was called Barspar, we halted at a well and asked a woman who was drawing water there to pour some into our lotas or brass pots. Respectfully she refused. She belonged to the Chamar or leather-worker caste, she explained, and for high-caste holy men like ourselves contact with anything that she had touched would mean pollution.

Buddharakshita and I could hardly believe our ears. The woman at the well was saying exactly the same thing as the Mātaṅgī woman had said to Ānanda, cousin and personal attendant of the Buddha, 2,500 years ago, and saying it in exactly the same circumstances. History was repeating itself. Making exactly the same reply as Ānanda had done, we told the woman that what we wanted was water, not caste. Whereupon she gladly filled our lotas. India had not changed much since the days of the Buddha, it seemed.”

When the rainy season struck, Buddharakshita decided to go and study in Ceylon.

Sangharakshita, still without identification papers, was offered a place to stay by Bhikkhu Jagdish Kashyap at the Benares Hindu University

In less than a week I was feeling perfectly at home in my new surroundings, and had embarked on a course of study that was to keep me busy – almost without interruption – for seven of the quietest and happiest months I have ever known.[...]

Our day began at dawn. After we had breakfasted on tea and toast (the latter saturated with ghee and sprinkled with sugar) I read Pāli, Abhidhamma, and Logic with Bhikkhu Kashyap, then returned to my room and did the exercises he had set me. This kept me busy until noon, when we had the usual rice-and-curry lunch. Bhikkhu Kashyap, mindful of the Indian equivalent of ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away,’ always rounded off the meal by chewing a couple of cloves of raw garlic. In the afternoon, having enjoyed a brief siesta, I either studied on my own, referring to my teacher occasionally if necessary, or engaged in literary work. …

When I entered his room (the communicating door was always left open) it was generally to find him stretched out on his string bed like a stranded whale, sound asleep… On my coughing, or murmuring ‘Bhante!’ a single eyelid would twitch, whereupon I would put my question, which was generally on some knotty point of Pāli grammar, or Abhidhamma, or Logic, which I had not been able to unravel by myself. Without opening his eyes, and without moving, Kashyap-ji would proceed to clear up the difficulty, heaving the words up from the depths of his enormous frame and rolling them around on his tongue before releasing them in slow, deliberate utterance. Sometimes he rumbled on for only a few minutes, sometimes for half an hour. Whatever he said was clear, precise, and to the point. If I asked about a particular passage of text, he always knew whereabouts it came, what had come before, and what followed. Yet all the time he had hardly bothered to wake up. As I returned to my room I would hear behind me a sigh and a snore and before I had settled down at my table Kashyap-ji would be sound asleep again.”

Throughout his life, Sangharakshita had been a keen poet

‘Above me broods…’ (1948)

Above me broods

A world of mysteries and magnitudes.

I see, I hear,

More than what strikes the eye or meets the ear.

Within me sleep

Potencies deep, unfathomably deep,

Which, when awake,

The bonds of life, death, time and space will break.

Infinity

Above me like the blue sky do I see.

Below, in me,

Lies the reflection of infinity.

But now, a tension grew between the aspiring monk-scholar and the poet within

‘Above me broods…’ (1948)

Above me broods

A world of mysteries and magnitudes.

I see, I hear,

More than what strikes the eye or meets the ear.

Within me sleep

Potencies deep, unfathomably deep,

Which, when awake,

The bonds of life, death, time and space will break.

Infinity

Above me like the blue sky do I see.

Below, in me,

Lies the reflection of infinity.

– Complete Poems (CW25, p.175)

One day this tension dramatically came to a head

“The conflict was … between Sangharakshita I and Sangharakshita II. Sangharakshita I wanted to enjoy the beauty of nature, to read and write poetry, to listen to music, to look at paintings and sculpture, to experience emotion, to lie in bed and dream, to see places, to meet people. Sangharakshita II wanted to realize the truth, to read and write philosophy, to observe the precepts, to get up early and meditate, to mortify the flesh, to fast and pray.

… What they ought to have done, of course, was to marry and give birth to Sangharakshita III, who would have united beauty and truth, poetry and philosophy, spontaneity and discipline; but this seemed to be a dream impossible of fulfilment. For the last two and a half years Sangharakshita II had ruled practically unchallenged. …

Angered by the encroachments of Sangharakshita I, who was reading more poetry than ever, and who had written a long poem which, though it had a Buddhist theme, was still a poem, Sangharakshita II suddenly burned the two notebooks in which his rival had written all the poems he had composed…

After this catastrophe, which shocked them both, they learned to respect each other’s spheres of influence. Occasionally they even collaborated, as in the completion of the blank verse rendition of the five paritrāṇa sūtras that had been started in Nepal. There were even rare moments when it seemed that, despite their quarrels, they might get married one day.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, pp.451-2)

Soon afterwards, Sangharakshita decided to take drastic action to “get rid of, or get beyond” the egoistic will... “In Seeds of Contemplation [by Thomas Merton] I found what I wanted, or at least a clear enough indication of it. The disciple should surrender his will absolutely to the will of his spiritual superior. In small matters as in great he should have no will of his own, not even any personal wishes or preferences. This was the secret. This was the way to subjugate the ego, if not to destroy it completely.

Though the idea was certainly not unfamiliar to me, it had never struck me so forcibly before, and I resolved to apply it forthwith to my relations with Kashyap-ji. In future his wishes would be my law. I would have no wishes of my own. Whenever he asked me if I would like to do something, as in the goodness of his heart he often did, I would reply that I had no preference in the matter, and that we would do just as he wished.

For the remainder of the time that we were together I faithfully adhered to this resolution. As a result, I had no troubles, and experienced great peace of mind.”

– The Rainbow Road from Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong (CW20, pp.463-4)

...which led him to take his guru's words very seriously.

“After weeks of indecision, Kashyap-ji had finally made up his mind not to return to the Benares Hindu University. Instead, he would spend some time meditating in the jungles of Bihar, where a yogi whom he knew had a hermitage. Perhaps, as he meditated, it would become clear to him what he ought to do next. Meanwhile, I was to remain in Kalimpong. ‘Stay here and work for the good of Buddhism,’ he told me, squeezing himself into the front seat of the jeep that was taking him to Siliguri. ‘The Newars will look after you.’

There was little that I could say. Though I did not really feel experienced enough to work for Buddhism on my own, and though I doubted whether the Newars were quite so ready to look after me as Kashyap-ji supposed, the word of the guru was not to be disobeyed. Bowing my head in acquiescence, I paid my respects in the traditional manner, Kashyap-ji gave me his blessing, and the jeep was off.

I was left facing Mount Kanchenjunga.”

Left alone in Kalimpong to “work for the good of Buddhism”

“Stay here and work for the good of Buddhism…’

As the jeep that was taking Kashyapji down to Siliguri disappeared round a bend, I was left standing at the side of the road with my teacher’s parting words ringing in my ears. I was twenty-four years old.

Since becoming Kashyapji’s disciple seven months earlier I had not been separated from him for more than a few days, and now, barely three weeks after our arrival in Kalimpong, he had suddenly decided to leave me there. It was a brilliantly sunny day in March. Above me was the fathomless blue of the sky. Around me were the foothills of the eastern Himalayas, the great jagged ridges running together from all directions. In front of me, far away to the north, rising behind the exact middle of a gigantic saddleback, were the dazzling white peaks of Mount Kanchenjunga.

For the first time in my life I was on my own.”

“…in the weeks following Kashyapji’s departure, I grew accustomed to the idea of working for the good of Buddhism – even started to accept it.

‘Behind me the old/Gate shuts,’ declared the haiku. ‘Before me opens/A new gate of gold.’ For the last three years, perhaps longer, I had been concerned with the needs of my own spiritual life. That was the old gate that was shutting behind me. It was now time for me to start paying attention to the needs of others. That was the new gate that was opening before me – the new gate of gold.

But what would I have to do before I could go through that gate? Would anyone be willing to go through it with me? What would I find on the other side?”

Before long, Sangharakshita founded a new organization: the Young Men's Buddhist Association (YMBA)

“Some kind of loose organizational framework was clearly essential… Out of the discussions that took place between Swale, Dhammajoti, and myself, the idea of starting a Young Men’s Buddhist Association in Kalimpong eventually was born and hovered above our heads like a beautiful iridescent ball…

I would bring the beautiful iridescent ball down to earth. I would embody it in an organization through which I would work for the good of Buddhism – work for the benefit of others – not only in Kalimpong but throughout the district, perhaps even beyond.

At the beginning of May, therefore, a meeting was convened at the Dharmodaya Vihara, the iridescent ball was invited to descend, and the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, Kalimpong, came into existence.”

“[Stepping-Stones would be] a monthly magazine of Himalayan religion, culture, and education. It would not be just another scholarly publication but a journal of living Buddhism.

It would be imbued with the all-embracing spirit of the Mahāyāna and would include articles on the Buddhist traditions of Tibet, of Sikkim, of Bhutan, and of Nepal. There would be poetry and short stories, extracts from the great Mahāyāna sūtras, and news of YMBA activities. We would send it out not only all over the district, but all over India, all over the world.

Thus above the beautiful iridescent ball that was the idea of the YMBA there hovered a second ball, in some ways even more beautiful and iridescent than the first – a ball that would send out even more brilliant flashes and be seen even farther afield.”

On 24 November 1950 he received full bhikkhu ordination at Sarnath

But Sangharakshita was broadening out from his individual practice as a Theravādin monk to embody the altruistic emphasis of the Mahāyāna

His friendship with Lama Anagarika Govinda affirmed this ecumenical approach

“For Lama Govinda, Buddhism was not to be identified with any particular conceptual expression. Buddhism was a matter of spiritual experience, and spiritual experience was something that could be put into words only to a very limited extent…

To cling to outmoded forms of spiritual life and thought was disastrous. Spiritual things could not be ‘fixed’…

Having understood that spiritual life was a process of organic growth, we would cease to judge the various phases of Buddhist history as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. We would develop genuine tolerance for all schools of Buddhism, even though we might be more strongly attracted to one school than to another. Just as the real nature of the tree lay in the organic development and relationship of all its parts, so the essential nature of Buddhism could be found only in a development in time and space that included all its different schools.”

– Facing Mount Kanchenjunga (CW21, pp.244-5)

On 24 November 1950 he received full bhikkhu ordination at Sarnath

But Sangharakshita was broadening out from his individual practice as a Theravādin monk to embody the altruistic emphasis of the Mahāyāna

His friendship with Lama Anagarika Govinda affirmed this ecumenical approach

While his friendship with Dhardo Rimpoche gave him a clear vision of the Bodhisattva Ideal

“I knew that he had been born in Dhartsendo, in eastern Tibet; that his father was a merchant; that at an early age he had entered Drepung Gompa, the great Gelug monastic university near Lhasa; that he had passed all his examinations with great credit; that his teacher was strict but kind; that a breakdown in his health had prevented him from completing his studies at the Tantric College, where the routine was demanding and conditions harsh; that in 1947, at the age of twenty-nine, he had come to India in search of health; and that on his return, after he had been back only eighteen months, the Dalai Lama’s government had appointed him abbot of the Tibetan monastery at Bodh Gaya, thus obliging him to make the long and arduous journey to India for the second time.

“…the better I knew him the more I liked and respected him. I saw how unassuming he was, how kind, and how mindful in everything he did. Later, in Kalimpong, I had many opportunities, over the years, of observing his great and noble qualities. I saw how helpful he was to visiting Western scholars, how utterly devoted to the welfare of the pupils of his school, how patient with his irascible old mother, and how independent in his dealings with Tibetan officials, most of whom expected from other Tibetans only subservience. In short, Dhardo Rimpoche manifested in his life to a high degree the ‘perfections’ (pāramitās) of generosity (dāna), ethics (śīla), patience (kṣānti), energy (vīrya), concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (prajñā), the practice of which for the benefit of all beings made one a bodhisattva”

– Precious Teachers (CW21, pp.242-3)

India, and which did not cease with my departure for England. It was a friendship in the course of which Dhardo Rimpoche and I worked closely together for the good of Buddhism, especially in Kalimpong. ”

– Precious Teachers (CW21, p.240)

On making contact with the scheduled caste leader, Dr B.R. Ambedkar, he was further encouraged

“I had written to him expressing my appreciation of his article ‘The Buddha and his Religion’, and telling him about the formation of the YMBA. About ten days later I received an encouraging reply…

‘Great responsibility lies on the shoulders of the Bhikkhus if this attempt at the revival of Buddhism is to be a success. They must be more active than they have been. They must come out of their shell and be in the first rank of the fighting forces. I am glad you have started the YMBA in Kalimpong. You should be [even] more active than that.’ ”

– Precious Teachers (CW21, p.90)

Sangharakshita was becoming more concerned with practising the ‘breadth and depth’ of Buddhism

In 1954, he gave voice to this wide-ranging vision in a series of lectures which were later published as A Survey of Buddhism

“The Mahāyānists, their spiritual life dominated by the absolute altruism of the bodhisattva ideal, are on the whole much more deeply aware of the instrumental character of ethics, and when circumstances demand it do not hesitate to augment, modify, and even to abrogate the minor rules, particularly if the promotion of the spiritual welfare of beings seems to require it.

…the rise of Mahāyāna Buddhism was from one point of view a protest against the increasingly negative attitude of the Hīnayānists and an attempt to recapture the spirit of the Original Teaching.

…Supreme Wisdom does not consist in the knowledge of an Absolute but in the understanding of the true nature of dharmas.”

In 1955 he met Dr Mehta, a mystic, and former physician for Mahatma Gandhi, whose ‘guidance from God’ inspired a turning inwards

“I made a special effort to deepen my meditation. Though I had been meditating for a number of years, my achievements in this field were far from commensurate with my aspirations. There were experiences of the bliss and peace of the lower dhyānas; there were visions, usually of the Buddha or Avalokiteśvara; there were flashes of insight, not always in connection with the meditation itself: and that was about all. What I now had to do, I felt, was to achieve a level of meditative experience which would enable me to receive whatever might be the Buddhist equivalent of Dr Mehta’s ‘guidance’, for much as I rejected the possibility of guidance by God (a being in whose existence I did not believe) I was well aware that for real spiritual progress to take place the ego, or ‘defiled mind-consciousness’ (as the Yogācāra termed it) needed to open itself to the influence of what I was later to call ‘the transcendental outpourings of the Absolute”

– In the Sign of the Golden Wheel (CW22, pp.299-300)

But one day while staying with Dr Mehta's ‘Servants of God’, he felt an overwhelming desire to leave... “Though the pasturage at Mayfair was indeed green, and though I could happily have grazed on it for a while (Dr Mehta wanted me to go on a meditation retreat there), I knew that it was essential for me to be on my way and that I could not spend more than a few days with my Bombay friends.

How I knew this I was unable to say, any more than I was able to say why it was essential for me to be on my way. I did not hear an inner voice, neither did I have a sudden intuition. It was simply that I knew, clearly and certainly, that I had to be on my way, and accordingly fixed my departure for 5 December.”

Taught hundreds of thousands of new Buddhists after Dr Ambedkar's death

While with friends in Bombay, Sangharakshita had a strong feeling that he ‘had to be on his way’

He went to Nagpur where, weeks earlier, Dr Ambedkar had converted to Buddhism along with 400,000 Scheduled Caste followers

When Sangharakshita's train arrived in Nagpur, there were 2,000 new Buddhists waiting for him – eager to learn more about their new religion

“On the occasion of that visit, more than two years earlier, my arrival in Nagpur had attracted little attention. Only Kulkarni was waiting on the platform to receive me, and he had taken me to his – or rather his brother’s – house in Dharampeth by taxi with a minimum of fuss. This time it was very different.

As the train came to a halt I saw that the platform was a solid mass of excited, white-clad figures. There must have been 2,000 of them and I realized, with a shock of astonishment, that they were all new Buddhists and that they had come to receive me. Kulkarni was also there, and on my emerging from the carriage he and the office-bearers of the Indian Buddhist Society (which Ambedkar had founded a year or two earlier, and which had been responsible for the organizing of the mass conversion ceremony) pushed their way through the crowd towards me. I was profusely garlanded, and then to repeated shouts of ‘Victory to Baba Saheb Ambedkar!’ and ‘Victory to Bhikshu Sangharakshita!’ was led to the waiting car…”

But just hours later, Sangharakshita received terrible news

“…there was a sudden commotion in the yard outside and a few seconds later three or four members of the Indian Buddhist Society burst into the little outhouse.

‘Baba Saheb’ was dead.

… The bearers of these dire tidings were not only in a state of deep shock but utterly demoralized. They were barely able to tell me that the Society’s downtown office was being besieged by thousands of grief-stricken people who, knowing of my presence in Nagpur, were demanding that I should come and speak to them. … I therefore told my visitors to organize a proper condolence meeting.”

Sangharakshita was called to respond to the crowds of mourners

“About 100,000 people had assembled. … Though some five or six of Ambedkar’s most prominent local supporters one by one attempted to pay tribute to their departed leader, they were so overcome by emotion that, after uttering only a few words, they burst into tears and had to sit down. Their example was contagious. When I started to speak the whole vast gathering was weeping, and sobs and groans filled the air. In the cold blue light of the petromax I could see grey-haired men rolling in agonies of grief at my feet.

“Though deeply moved by the sight of so much anguish and despair, I realized that for me, at least, this was no time to indulge in emotion. Ambedkar’s followers had received a terrible shock. They had been Buddhists for only seven weeks, and now their leader, in whom their trust was total, and on whose guidance in the difficult days ahead they had been relying, had been snatched away.

“… faced by the unrelenting hostility of the caste Hindus, they did not know which way to turn and there was a possibility that the whole movement of conversion to Buddhism would come to a halt or even collapse. I therefore delivered a vigorous and stirring speech in which, after extolling the greatness of Ambedkar’s achievement, I exhorted my audience to continue the work he had so gloriously begun and bring it to a successful conclusion. ‘Baba Saheb’ was not dead but alive. To the extent that they were faithful to the ideals for which he stood and for which he had, quite literally, sacrificed himself, he lived on in them.”

The revival of Buddhism in India was almost lost, but Sangharakshita's presence in Nagpur was seen as a ‘miracle’ “In the course of the next four days I visited practically all the ex-Untouchable ‘localities’ of Nagpur, of which there must have been several dozen, and addressed nearly thirty mass meetings, besides initiating about 30,000 people into Buddhism … When the time came for me to be again on my way I had addressed altogether 200,000 people and forged, incidentally, a very special link with the Buddhists of Nagpur, indeed with all Ambedkar’s followers.”

– In the Sign of the Golden Wheel (CW22, p.363)

“Dr Ambedkar’s followers told me that they felt my being there at that critical juncture was a miracle and that I had saved Nagpur for Buddhism. Had I not been there, there is no knowing what might have happened.”

The revival of Buddhism in India was almost lost, but Sangharakshita's presence in Nagpur was seen as a ‘miracle’

“In the course of the next four days I visited practically all the ex-Untouchable ‘localities’ of Nagpur, of which there must have been several dozen, and addressed nearly thirty mass meetings, besides initiating about 30,000 people into Buddhism … When the time came for me to be again on my way I had addressed altogether 200,000 people and forged, incidentally, a very special link with the Buddhists of Nagpur, indeed with all Ambedkar’s followers.”

– In the Sign of the Golden Wheel (CW22, p.363)

On his return to Kalimpong, he heard Chattrul Sangye Dorje was in town

“Dr Ambedkar’s followers told me that they felt my being there at that critical juncture was a miracle and that I had saved Nagpur for Buddhism. Had I not been there, there is no knowing what might have happened.”

“‘Chattrul’ meant something like ‘without affairs’ or ‘without concerns’ and the sobriquet had been bestowed on him on account of his complete indifference to such things as organized monasticism and ecclesiastical position. It was not even clear whether he was a monk or a layman. He roamed freely from place to place, no one knowing where he was going to turn up next or how long he would stay. He was an accomplished yogi, having spent many years in the solitudes of eastern Tibet, meditating; and if popular report was to be believed, he possessed many psychic powers and was a great magician.”

Chattrul told Sangharakshita that his yidam was Green Tārā, the Bodhisattva of spontaneous compassionate activity and initiated him into her visualization practice (sādhana)

“Though unable to accept Dr Mehta’s ‘guidance’ on his (or its) own terms, [see 1950 chapter] I had taken very much to heart his insistence that in the spiritual life the best and most reliable guidance was that which came from beyond one’s ego. For me it could not come from God, but perhaps it could come from one or other of those transcendental beings who according to the Buddhism of Tibet (as of that of China and Japan) were the different, infinitely various, aspects of the Buddha’s sambhogakāya or ‘body of glory’ – the supra-historical ‘body’ in which he communed with advanced bodhisattvas and they with him.

Chattrul Rimpoche showed no surprise at my request. In fact he seemed rather pleased, and after a moment of inner recollection told me that my yidam was Dolma Jungo or Green Tārā, the ‘female’ bodhisattva of fearlessness and spontaneous helpfulness, adding that Tārā had been the tutelary deity of many of the great pandits of India and Tibet. In other words, I had an affinity with Green Tārā, in the sense that she was the transcendental counterpart of my own mundane nature and that I could, therefore, more readily come to a deeper understanding of myself through devotion to her.”

– In the Sign of the Golden Wheel (CW22, pp.374-5)

Chattrul also predicted that Sangharakshita would soon have his own monastery

Six weeks later he received funding from a friend to buy one

Received tantric initiations from leading Tibetan lamas

Sangharakshita had become known as a key figure in the multi-religious Kalimpong community “In the course of my second seven years in Kalimpong I developed the Triyana Vardhana Vihara as a centre of interdenominational Buddhism. Thai, Vietnamese, and Tibetan monks came to stay with me, and there was even the occasional Western Buddhist.

“Much of my time when I was actually in Kalimpong was spent at my desk, and my literary output during this period included the books later published as The Three Jewels and The Eternal Legacy. At the suggestion of a friend I also started writing my memoirs.

“When not in Kalimpong I was usually to be found either in Calcutta, editing the Maha Bodhi Society’s monthly journal, or touring central and western India preaching to the followers of Dr Ambedkar. The fourth and longest of my preaching tours lasted from October 1961 to May 1962. In those eight months I visited more than half the states of India, gave nearly 200 lectures, and received 25,000 men and women into the Buddhist community.”

– Moving Against the Stream (CW23, p.19)

Between the years of 1957 and 1963, he received tantric initiations from five more Tibetan lamas:

In 1957, Jamyang Khysente Rimpoche gave Sangharakshita four sādhanas: Avalokiteśvara, Mañjuśrī, Vajrapāṇi and Green Tārā

“The painting [he gave me] was not so well executed as he could have wished, Jamyang Khyentse told me, though it was the work of the best artist he had been able to find in Gangtok; and indeed, the work was clumsily if painstakingly done, the rays of rainbow light that emanated from Mañjughoṣa’s body terminating in a ring of solid-looking rainbow balls. But I was too deeply moved by the Rimpoche’s kindness in giving me the thangka, which had been painted in accordance with his directions, to be much concerned about any shortcomings it might have.

“Moreover, there was a special significance in his giving me the thangka. As he proceeded to explain, through the initiations he had given me he had transmitted to me the essence of the teachings of the great masters who were depicted in it. I was now their spiritual heir and successor. Smiling, he then pointed to the yellow-robed figures in their caves, one meditating and one teaching. Both were me.” – Precious Teachers (CW22, p.407)

Dudjom Rimpoche gave him the Vajrasattva ‘Hell Annihilator’ sādhana in 1959 “When I received the Vajrasattva abhiṣeka from Dudjom Rimpoche there was … a point at which I definitely felt something pass from him to me, but it was not something that could be described in terms of power….”

“Once or twice, when the weather was hot, he slipped his arms out of his bokku and sat with empty sleeves knotted round his waist in the rather swashbuckling style favoured by some Tibetan men. On another occasion – it may have been when giving the Vajrasattva initiation – he sported a stetson and a colourful Hawaiian shirt, into the breast pocket of which was stuffed a thick wad of currency notes. His long hair was usually plaited into a braid and wound round his head. Sometimes he wore it spread out on his shoulders, which accentuated the rather feminine cast of his features, and sometimes, again, he tied it in a topknot like a yogi.” – Precious Teachers (CW22, pp.502-3 & 508)

In 1962 he received the Padmasambhava abhiṣeka and the name ‘Urgyen’ from Kachu Rimpoche

“ I received the [[[Padmasambhava]]] abhiṣeka on 24 October 1962. The following morning I went into town and on my way through the bazaar happened to see a Tibetan monk squatting at the roadside. In his lap was a small bundle of rather grubby xylograph texts that he was offering for sale. Since the monk was obviously in need of money, and since the texts were very cheap (so cheap that even I could afford to buy them), I at once bought them and returned with them to the Vihara, where I showed them to Kachu Rimpoche. His response was one of surprise and delight. They were Nyingma texts, he exclaimed joyfully, as he thumbed his way through them. Most of them had to do with the Greatly Precious Guru, and the fact that I had come across them so soon after receiving the abhiṣeka, and in such a totally unexpected manner, was extremely auspicious. It showed that I had a special connection with the Greatly Precious Guru, and with the Nyingma tradition, and that my efforts to realize the import of the teachings which the abhiṣeka had empowered me to practise would prove successful.…

Among the texts I had bought [were instructions for] the Going for Refuge and Prostration practice.…

Having received further instruction from Kachu Rimpoche, I therefore took up the Going for Refuge and Prostration practice, as well as the other mūla yogas, and continued to do it regularly until my departure for England two years later.”

– The History of My Going for Refuge (CW2, pp.442-3)

In 1962 his friend Dhardo Rimpoche bestowed on him the Bodhisattva Ordination as well as the White Tārā and Medicine Buddha sādhanas

“Dhardo Rimpoche not only gave me the bodhisattva ordination but subsequently explained the sixty-four bodhisattva precepts to me in considerable detail, so that I was able to translate them from Tibetan into English.…

“[The bodhisattva ordination made me] think of myself not as a monk who happened to accept the bodhisattva ideal but rather as a (triyāna) Buddhist who happened to be a monk. Since the arising of the bodhicitta – and becoming a bodhisattva – was in fact the altruistic dimension of Going for Refuge, this in turn had the effect of making me think of myself simply as a monk who went for Refuge, or even as a human being who went for Refuge and who happened to live in monastic or semi-monastic fashion. Commitment was primary, lifestyle secondary.”

In 1963 Dilgo Khysente Rimpoche gave Sangharakshita an Amitābha phowa practice and the Kurukullā and Jambhala sādhanas

“Despite his being so eminent a lama, and so revered, it would have been difficult to find a more unassuming person than Dilgo Khyentse Rimpoche, or one who was more approachable.… I was visiting him regularly, and I never felt that I was being intrusive, or that I was wasting the Rimpoche’s time. On the contrary, I felt that I was more than welcome. I always found the Rimpoche sitting cross-legged on his bed, a Tibetan xylograph volume in his lap.

“On my entering the tiny front room, he always looked up from his book with a little smile of recognition and pleasure, and his wife always came in after a few minutes with the Tibetan tea and, perhaps, some Tibetan bread. After a few such visits I observed that the Rimpoche never gave the impression of being disturbed or interrupted in what he was doing. His attention seemed to pass smoothly and seamlessly from one thing to another, as though all were equally interesting, equally important, and equally enjoyable, whether it was reading his book, answering a question from me, or drinking his tea.It was no different when, on 9 May 1963, he transmitted to me the phowa or ‘consciousness transference’ of Amitābha, an oral tradition of the Nyingmapas. Once again I was able to observe how seamlessly his attention passed from one thing to another, passing on this occasion from whatever it was he had been doing before to the business of explaining to me the details of the practice and performing the simple ritual within whose context the transmission took place.”

– Precious Teachers (CW22, pp.554-5)

“Not unnaturally, the vast majority of the newly converted Buddhists had no wish to go to Ceylon or Thailand, or to become monks, or even to spend several years studying Pāli. They did, however, very much want to know more about Buddhism and if anyone took the trouble to explain it to them in a way that they could understand their joy, enthusiasm, and gratitude knew no bounds. Certainly this was my own experience when, as a result of the link that I had forged with them in Nagpur during the anxious days immediately following Ambedkar’s death, I undertook a series of four preaching tours that lasted, with very little intermission, from February 1959 to May 1961. In the course of these tours I visited cities, towns, and villages in more than half the states of India, opened temples and libraries, installed images of the Buddha, performed name-giving ceremonies and after-death ceremonies, blessed marriages, conferred with leading members of the Indian Buddhist Society, held a special training course, delivered about 400 lectures and personally initiated upwards of 100,000 people into Buddhism. ”

“For them taking the Refuges and Precepts, or becoming Buddhists, meant conversion in the true sense of the term. It meant not only the repudiation of Hinduism, not only deliverance from what Ambedkar called ‘the hell of caste’, but also being spiritually reborn in the sense of becoming free to develop in every aspect of their lives, whether social, economic, cultural, or religious. Indeed, as I could see from the light in their eyes and the rapturous look on their faces, in repeating the words of the ancient Pāli formula the ex-Untouchables, far from just ‘taking pansil’, were in fact giving expression to their heartfelt conviction that Buddhism was their only hope, their only salvation. They were Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels.”

– The History of My Going for Refuge (CW2, p.438)

During this period, Sangharakshita extensively toured the villages of Ambedkar’s followers, teaching them about their new religion

Bhikkhu Khantipālo, a fellow English monk, stayed with him at the vihara and joined him for Dharma teaching tours

“Our relationship in the Kalimpong vihara was a mixture of both master-pupil and fellow practitioners”

– Noble Friendship by Khantipālo (p.86)

The two English monks were invited to hear an extensive account of Buddhist meditation by Yogi Chen, the last of Sangharakshita’s main teachers

“He was living as a hermit in a small bungalow… During the whole time that I was in Kalimpong he didn't go out even once.…

“He spent the greater part of the day engaged in different forms of meditation.… He had all sorts of strange visions and psychic and occult experiences.”

– My Eight Main Teachers (CW12, pp.443-4)

Sangharakshita was working hard to spread the Dharma and enjoying his stimulating life in Kalimpong, where he’d now lived for 14 of his 20 years in India/South Asia.

He could easily have stayed there for the rest of his life, when he received a letter from the English Sangha Trust inviting him back to the UK...

Initially reluctant to leave India, which he'd come to consider his home, Sangharakshita was convinced by his friends to return to England

“At the time I saw myself as being permanently settled in India, which I had come to regard as my spiritual home. In Kalimpong, within sight of the snows, I had a peaceful hillside hermitage, the Triyana Vardhana Vihara, where I could meditate, study, write, and receive my friends, and from which I sallied forth on my preaching tours in the plains and to which, when I needed to recoup my energies, I could return. Above all, I had spiritual teachers of exceptional attainments, with most of whom I was in regular personal contact, and from whom I derived not just knowledge but inspiration.

Thus there was little incentive for me to return to the land of my birth, much as I loved its language and its literature, and at first I was undecided whether or not to accept the [English Sangha] Trust’s invitation.

Khantipālo was with me when it arrived, however, and when he pointed out that it was my duty to help spread the Dharma in England, inasmuch as I had been born and brought up there, I could not but recognize the force of his argument.”

– Precious Teachers (CW22, pp.560-61)

He arrived at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, run by a small group of Theravādin monks for the English Sangha Trust

“I remember having breakfast in the basement next morning [after arriving] with Ānanda Bodhi and the three novices. There was a choice of four or five different hot drinks, and at the centre of the table, besides jam, marmalade, and honey, there were various spreads quite new to me. In my own monastery in Kalimpong we drank only tea, and jam had been seen there on only one occasion when, plums being unusually cheap that year, we had made a couple of dozen jars of it. As I was going upstairs to my room after the meal I heard the oldest of the novices ordering supplies on the phone. ‘You’ve only two kinds of salmon?’ he was saying. ‘Then send the more expensive kind.”

After some resistance, he was recognised as the senior monk at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara

“To the left of the shrine, and to the right, two chairs had been placed, and on one of the chairs next to the shrine there was an embroidered cushion. When Ānanda Bodhi at last swept in, he straightway plumped himself down on the chair with the embroidered cushion, as if it were his by right. Vimalo at once objected. ‘We ought to let Venerable Sangharakshita sit there,’ he said bluntly, ‘as he is senior to us.’ Whereupon the Canadian monk vacated the chair with a very ill grace, I took my seat on it, and our meeting began.… Ānanda Bodhi took very little part in the proceedings. His being compelled to relinquish the seat of honour had shaken him badly, and he may have been thinking that the incident represented a deposition from the throne of his hitherto unquestioned supremacy at the Vihāra and within the English Sangha [[[Trust]]]”

– Moving Against the Stream (CW23, p.26) “I remember having breakfast in the basement next morning [after arriving] with Ānanda Bodhi and the three novices. There was a choice of four or five different hot drinks, and at the centre of the table, besides jam, marmalade, and honey, there were various spreads quite new to me. In my own monastery in Kalimpong we drank only tea, and jam had been seen there on only one occasion when, plums being unusually cheap that year, we had made a couple of dozen jars of it. As I was going upstairs to my room after the meal I heard the oldest of the novices ordering supplies on the phone. ‘You’ve only two kinds of salmon?’ he was saying. ‘Then send the more expensive kind.”

– Moving Against the Stream (CW23, pp.6-7)

He arrived at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, run by a small group of Theravādin monks for the English Sangha Trust

“‘Insight meditation’, at least in the extreme form taught by Ānanda Bodhi, in conjunction with the Canadian monk’s brash and arrogant personality, had been responsible, at least in part, for the breach between the Sangha Association and the Buddhist Society. If that breach was to be healed, and if more people were not to be turned into zombies in the name of Buddhist meditation, then the teaching … would have to be phased out and the more traditional methods taught instead.”

– Moving Against the Stream (CW23, p.45)

He noticed that a meditation method that was being taught was having alienating effects and causing rifts in the fledgling British Sangha

So he introduced the cultivation of mettā (loving-kindness)

“Some people at the Summer School regretted that a wider range of meditation practices were not available. As one of them told me, ‘We aren’t attracted by Zen, and we don’t like Vipassanā, and there doesn’t seem to be anything in between.’ Actually there is very much ‘in between’. At the 9.30 meditation sessions I conducted an experiment in what I [afterwards] called Guided Meditation, the class progressing from one stage to another of Mettā Bhāvanā (Development of Love) practice as directed at five-minute intervals by the voice of the instructor. Verbal directions were gradually reduced to a minimum until, in the last session, transition from one stage to the next was indicated merely by strokes of the gong. The experiment seemed successful…”

– Twenty Years After (CW27 p. 37)

And taught at the Buddhist Society Summer School, as well as around the UK

After one lecture, a young man approached him with a ‘startling claim’…

Dismissed by the English Sangha Trust amid rumours of homosexuality

Sangharakshita was giving a lecture about the Tibetan Book of the Dead when he was approached by a man who claimed to have ‘seen the pure white light’

“Had almost anyone else made such a startling claim I would have been inclined to think he was either crazy or a charlatan, but so unassuming was the young man’s demeanour, and so frank and trustful his gaze, that it was impossible for me not to believe that he spoke the truth.…

“Terry’s parents may not have actually labelled him a schizophrenic, but they certainly regarded his evident dislike of what he called ‘the stereotyped living of suburbia’ as a sign of mental illness or, at least, of there being something seriously wrong with him. The treatment Terry was given at Villa 21 was simple and, in a sense, drastic. He was given ether.… As he wrote shortly afterwards,

‘As Dr Caple administered the ether so my mind seemed to ascend one level of understanding after another. Time was the first fiction to be exposed coupled with the crippling effects that personality has upon a person’s true self. As my awareness increased the frequency at which my mind seemed to function was fantastic and in contrast to that of my surroundings...’

“The ether experience had a permanent effect on Terry’s thinking. It left him convinced that for human beings there were two possible approaches to reality. They could either develop an understanding of themselves and their environment over scores of lifetimes, and experience reality as the reward of their creative effort to evolve; or they could simply see that the truth, pure and unadulterated, was and always had been available and that it moreover was capable of being experienced here and now, whether by means of fasting or meditating or as the result of a drug abreaction such as he had undergone. He also realized that in the course of a lifetime a human being had to put in what seemed an unbelievable amount of effort and discipline, and this ‘hideous, self-imposed struggle’ he found so upsetting, when recovering after his first session of treatment, that he burst into tears.”

Terry Delamere and Sangharakshita quickly formed a close spiritual connection

“As we got to know each other, a friendship did develop – and develop rapidly. We discovered we had a spiritual, even a transcendental affinity, and communication between us accordingly deepened.

“At Biddulph [[[meditation retreat]]] it had deepened still further, with the result that by the end of Terry’s week there with me I was not only well satisfied with the progress of our friendship but felt I understood him better than before. Perhaps I understood myself better too.” – Moving Against the Stream (CW23, p.149)

This friendship was a catalyst for Sangharakshita moving beyond monasticism – he began to wear ‘civilian clothes’

“I should stress, to avoid possible misunderstanding, that there was never any question of sex between Terry and I.

“He would simply not have been interested and that was not the nature of our friendship. But my contact with him did help me to move away from even my own, by then, very attenuated version of Theravada Bhikkhu-hood…”

– Conversations with Bhante

This friendship was a catalyst for Sangharakshita moving beyond monasticism – he began to wear ‘civilian clothes’

“Terry was pleased to see me in civilian clothes, for he was one of those who believed that such oriental trappings as yellow robes had nothing to do with the actual study and practice of the Buddha’s teaching and could, in fact, be an obstacle to its being taken seriously by intelligent people.…

“Nobody at the Hampstead Vihara knew that I sometimes wore civilian clothes… Had the more decidedly Theravādin members of the Sangha Association known they would have been scandalized.…

“My finally deciding against getting myself a jacket, when Terry and I looked down Charing Cross Road for one, was certainly not owing to any shortage there either of clothing shops or jackets. Rather was the opposite the case. There were several such shops, and in each shop there were so many jackets, of so many different sizes, colours, materials, styles, and prices, that in the end, unable to make up my mind which one to choose, I decided to put off the whole perplexing business to another day, with the result that several years were to pass before I actually bought myself one.… I had been away so long that I had no idea what sort of clothes would be suitable for someone of my age and position (or lack of position)…”

Sangharakshita and Terry went travelling together, driving to Greece via Italy

“In my teens I had read as widely as I could in the fields of European literature, art, and philosophy, both ancient and modern, and even during my twenty years in the East I had not entirely lost contact with Western culture, at least to the extent that this was represented by English poetry.

“For me our present journey, and the sightseeing we were doing along the way, represented a renewal, and a deepening, of that contact. The places we visited, and the paintings we saw, had meaning for me. Through them I was reconnecting with my cultural roots, reclaiming my cultural heritage, for although I was a Buddhist I was a Western Buddhist, and could not afford, psychologically and even spiritually, to cut myself off from those roots, or to renounce that heritage, as some misguided Western Buddhists thought they were obliged to do.”

Then to India, for a farewell tour to old friends

While in India, Sangharakshita received a letter from the English Sangha Trust, withdrawing their support for him

“The trouble, as I have called it, had started with gossip about my relationship with Terry. That relationship, it was alleged, was of a homosexual nature, and as Toby [[[Wikipedia:Christmas Humphreys|Christmas Humphreys]]] had pointed out the English middle-class mind had an abhorrence that even the appearance of homosexuality was sufficient, it seemed, to warrant a man’s banishment from decent society or, as I had found, his removal from the position he occupied. What this meant in effect, at least in England, was that it was difficult for men to develop more than ordinarily close friendships without incurring the suspicion of homosexuality and, in some cases, the unpleasant and even painful consequences of such suspicion.”

(N.B. Homosexuality was still illegal in the UK in 1966. It was partially decriminalized in 1967.)

Explored sex, drugs and counter-culture

‘We were helped by the zeitgeist, the spirit of the times. I’m talking about the late sixties and early seventies. Things were very different then… There was a different sort of atmosphere around. An atmosphere of experimentation and new things, changes in all sorts of walks of life. We had the Beatles, didn’t we, in those days. Some of you perhaps remember them?

‘And, of course, Zen was in the air; several of our own friends were interested in Zen. Ananda was very interested in Zen. So were several others. And of course, there was the smell of something which perhaps I shouldn’t mention in the air… It was the days of psychedelic drugs and experimenting with oriental music, new forms of literature. I remember Jack Kerouac’s novels were very popular in those days and in the FWBO too. And also Erich Fromm’s were very popular. So there was definitely a supportive spirit in those days. A spirit that was supportive of any new spiritual venture, rather than antagonistic to it.’

The FWBO attracted followers from the counter-culture movement

Sangharakshita embraced this new world and, at forty-two, had his first sexual experience

‘I had my critique of monasticism almost from the very beginning, which meant that I came to have more and more uncertainty about wanting to continue being a monk – which of course opened up the possibility of engaging in sexual activities...

‘I happened to go down to Sakura, our centre in Monmouth Street, one evening, on my way to a retreat, and there, unexpectedly, was Carter. He had arrived with a letter of introduction from Robert Aitken, the American Zen Roshi in Hawaii, and since he had nowhere to stay… he was allowed to spend the night in our basement shrine room at Sakura. When I went down to the centre the following afternoon to take a class, I found a number of people on the pavement outside, and Carter looking very ashamed and upset. He had gone to sleep, leaving a candle burning, and it had set the place on fire. He was lucky to have escaped with his life. Everyone was very annoyed with him and, of course, no-one wanted to give him house-space. So, what to do with him? Rather reluctantly, I offered to take him back to my flat. When it was bedtime, I asked him whether I should make up a bed for him on the floor or whether he would share my bed. Without hesitation he said he would sleep with me – and that was how our sexual relationship began.’

...and began to experiment with drugs

‘Carter and the members of the English Mystical School smoked quite a bit of marijuana and I would sometimes join them. Carter and I also smoked marijuana lying on the grass on Hampstead Heath, near which I lived. I remember having a very positive experience with the drug, just floating away as if on a magic carpet. I perhaps smoked 'dope' some 100 or so times, but after Carter left I never smoked again – and I never missed it.

‘I also took LSD with Carter… I had intended to write about the experience as it progressed, but all I could write was, “As if brain being nibbled by little fish....”!’

‘From one perspective, these activities were part of the wave of experimentation that characterised the Sixties. Sangharakshita let his hair grow, and wore his robes with a mixture of other clothes, or sometimes jeans and a sweater instead. He didn’t look out of place amid London’s burgeoning hippy life. But from another perspective, they represented Sangharakshita’s distinctive approach to Buddhism. He recognised that Buddhism needed to adapt to the changed circumstances of the modern world, setting aside many sectarian and culture-bound features of individual Buddhist traditions, but not losing touch with its core teachings and values.’

His relationship with Carter grew more complex and ended in

‘By this time Carter had his girlfriend in the person of Andrea… Sometimes he spent the night with me, sometimes with Andrea… On one of the rare occasions when the three of us went for a walk on Hampstead Heath together he put an arm round each of us and declared that it was the happiest time of his life, for he had with him the two people whom he loved best in the world…

‘I was quite happy that he should sleep with Andrea, but Andrea was not happy that he should sleep with me or see very much of me. One day Carter suggested that the three of us should spend a week together on holiday. Though he did not say so, I knew that he hoped that this would bind the three of us more closely together and help Andrea develop a more positive attitude towards me. I was sceptical, and told Carter that I did not think his scheme would work. I could see that Andrea was implacable in her dislike of me and that we would never be friends. Nonetheless, I allowed Carter to persuade me and agreed to take part in the experiment...

‘In the end I told Carter that the holiday was not proving a success and that we should separate, and to this he unwillingly agreed. There was an emotional parting and even Andrea seemed a little moved. He would return the car to Mike at the end of the week, then take the train back to London and me. ‘I never saw him again. ‘From friends of friends I learned that he had sent home for his best suit and that shortly afterwards he had married Andrea and taken her back to America with him. Before leaving he sent me a message. It was scribbled on a postcard with various coloured pencils and it read, ‘I know I am hurting you. Give me two years, and I will be back.’ I was indeed hurt. Carter had been an important part of my life for just over a year, and it took me a long time to recover from the loss.

Meanwhile, the FWBO was off to a slow start…

‘My hitherto rosy view of the FWBO was blemished when I realized that the number of active and dedicated Order members was in fact pitifully small, maybe no more than three or four from the two dozen or so that had been previously ordained in 1968 and 1969. The majority in fact had already drifted away. No doubt they sincerely considered themselves to be Buddhist, and no doubt they were happy to have been personally ordained by Sangharakshita but for whatever reason they were unable to comprehend his vision for a new Buddhist movement or appreciate the radical and demanding nature of Buddhism itself.’

‘If Sangharakshita had set out to create a mass, group-orientated movement he might well have succeeded in attracting far greater numbers. But from the earliest days Sangharakshita emphasized that the Buddha’s teaching was addressed to the human being as an Indvidual - not as a member of the group.

‘This emphasis on the Individual arose when a few of us tried to agree on a suitable title for the geminal FWBO newsletter. Sangharakshita’s suggestion was ‘The Earthworm’, because the earthworm goes invisibly about its business while remaining an influential and beneficial presence. As with many of Sangharakshita’s suggestions, it failed to find acceptance. Another of Sangharakshita’s ideas that failed to catch on was to produce for free distribution inexpensive ‘religious tracts’ that outlined the basic tenets of Buddhism. So much for his supposed authority!’

He spent a term in 1970 teaching at Yale University, USA, whilst his followers carried on FWBO activities

‘During my absence from England the responsibility for conducting regular meditation classes had devolved on a few of the more active and experienced members of the Order. On my return I was pleased to find that, far from there having been any falling off while I was away, attendance at these classes had actually increased, each of them now containing a sprinkling of faces that to me, at least, were entirely new. Indeed, I was not only pleased by this fact but enthused, for one of the main reasons for my accepting the invitation to Yale had been that this would give me an opportunity of finding out whether or not the movement in London, to which I had devoted three years of my life, was capable of standing on its own feet for three months. Being now assured that it could not only stand but even walk, I returned with renewed enthusiasm to the accustomed routine of meditation classes, meetings of the Order, public lectures, council meetings, seminars, and retreats.”

Later that year, the lease on Sakura expired and the FWBO was left without a home…

‘In late 1970 the lease on Sakura expired. The FWBO needed to find new premises, but they couldn’t find anywhere suitable in time. There followed a period of holding classes in different venues each week. Without a permanent home it was hard to hold the group together, and people started to drift away.

A 15-month period of uncertainty followed, while various people trudged the streets of London searching for a property they could afford. Eventually, Sangharakshita wrote to all the London boroughs asking for help. Two weeks later, in January 1972, a reply from Camden Council requested an urgent meeting. Sangharakshita went with Hugh Evans (later ordained with the Buddhist name Buddhadasa) to view a small, disused factory building in Balmore Street, Highgate. ‘Can you do it?’ asked Sangharakshita.‘I think so’, was Hugh’s reply. He gave up his job to become the first full-time worker for the FWBO and to establish the Archway Centre.’

With Sangharakshita’s support, as well as the dedication of a small group of friends, the first dedicated FWBO Centre was opened

Expanded the ‘Friends of the Western Buddhist Order’ (FWBO) into an international movement

He also began to lead seminars where he brought key Buddhist teachings to life in a new way

He particularly emphasised ‘spiritual friendship’ - kalyāṇa mitratā, encouraging deeper communication between people ‘All this time, Sangharakshita was overseeing the young movement. He could now work in a much less ‘hands on’ way and had more time to write, reflect, and provide teaching and spiritual inspiration. In December 1973, he gathered a group together and led a week-long seminar on the Bodhicaryavatara, a classic Mahayana text that emphasizes the altruistic dimension of the spiritual life. Each day they’d sit round in a circle, books in hand, he in robes and carpet slippers, an old reel-to-reel tape machine recording the proceedings, as he guided them carefully through the text, line by line. Between then and 1990, Sangharakshita conducted 150 seminars either on traditional Buddhist works or commentaries on them, or, occasionally, on non-Buddhist texts. The recordings were later transcribed by volunteers (in itself a huge labour of love) and made available for study. In later years, some of the material from them has been edited into books [e.g Living with Kindness, The Yogi’s Joy, etc.]. The seminar became Sangharakshita’s principal medium not just for imparting information about Buddhism, but also for teaching people how to read Buddhist texts, how to reflect on their teachings, and how to think critically. He brilliantly drew out the essentials from a text, revealing its profound depths, while also showing how it pertained to the practical and everyday.’

– The Triratna Story by Vajragupta (pp.17-18)

‘I know that this is one of our features that many people find especially attractive. I get many letters and visitors, and people often tell me the story of how they came in contact with our movement, sometimes after experiencing other forms of Buddhism. From what people tell me, I would say that the two things that draw most people to us and which they continue to value most are our clear presentation of the Dharma and the experience of sangha. That people appreciate this emphasis on spiritual friendship so much suggests that very often that element is lacking in the outside world. You may have friends, or at least acquaintances, but you may not have people whom you know so well that you can open your heart to them, and have a full and deep communication about everything that concerns you, whether material, practical, emotional, or spiritual.’

– ‘Forty Years On: The Six Distinctive Emphases of the FWBO’ (CW12, p.669)

Order members started moving beyond London, playing tapes of Sangharakshita’s lectures to small groups of friends

He visited these ‘branches’ of the FWBO as they sprung up throughout the 1970s – Finland, New Zealand, India, USA, and more

‘Where there is energy, there is the possibility of refinement of energy. The real problem is when there is no energy, i.e when energy is blocked, and unable to find any outlet in any direction, or at any level.’

– Travel Letters (CW24, p.60)

After a short sabbatical in 1973, Sangharakshita returned with an important message for the burgeoning Order

Thangka image of the thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara

‘And so this close circle of friends gathered under bright blue skies in the open landscape of the New Forest in Hampshire, eager to hear what Sangharakshita had to say. He was keen to talk to them about his developing vision for the FWBO, eager to speak in a new way. He was beginning to see the Western Buddhist Order as a tiny manifestation of Avalokiteśvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. In one of the forms in which Avalokiteśvara is depicted in the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist tradition, he has one thousand arms reaching out in all directions, each holding a different implement with which to help relieve the suffering of the world. The spiritual community of the FWBO really could be Avalokiteśvara made manifest in the world. Each Order member could be like one of those arms, holding his or her own particular implement, working in his or her own particular direction, each part of a greater whole, each joined as one spiritual body. If they were able to work together in this way, the whole would be far greater than the sum of the parts. They could be a tremendous force for good in the world.’

– The Triratna Story by Vajragupta (pp.12-13)

In 1974, he was given money from Buddhadasa to buy a small cottage named Albemar