Tibetan Buddhist Practices for Dying

This is a very deep and complex topic as the Tibetans have made a true science out of the process of dying. Ven. Palmo began by noting that from a Buddhist perspective, death is a stage of transition. It is merely an exchange of a rugged and old body of this life with a new and young body of the next, like changing of your clothes when they are old and worn out. Buddhists see death as a process and not as an end.

Ven. Palmo explained that in Tibetan culture in the case of a natural death pertaining to sickness or senility, the patient with his own intuition will feel the nearness of their death. They will then summon their children and explain how they would like them to help them die. They also advise them how to share their legacy and property in a proportionate way. While preparing to leave the body, they ask to invite a monk or a teacher to help them at the prime moment of dying. As per the wishes of their parent, the children will invite the monks to do the rituals for a peaceful dying. These are the eight prayers and chanting of the Medicine Buddha (Skt. Bhaishajya-guru, Jp. Yakushi-nyorai 薬師如来); Amida Buddha and White Tara initiation; making statues, thangkas, and doing a retreat to help in extending the life if possible. This includes releasing animals, doing prayers, giving alms (food, clothes etc) to the poor, and so on.

The actual dissolution of the body follows the dissolution of the 5 elements. The first element of earth dissolves, which corresponds to the dissolution of eye consciousness and of the form aggregate (Skt. rupa skandha). External signs are weakening of the body and shrinking of the limbs, as well as the closing of the eyes. Internal signs are the appearance of mirages and the feeling like a huge mountain is being pressed down upon the person. Then the earth element withdraws into the water element, and the patient begins to lose control of bodily fluid. This corresponds to the dissolution of sound consciousness and the feeling aggregate (vedana skandha). External signs are that bodily fluids begin to dry up. Internal signs are the appearance of smoke. Then the water element dissolves into the fire element with the mouth and nose drying up completely. All the warmth of our body begins to sweep away with the limbs getting cold. The breath gets cold as it passes though the mouth and nose. This corresponds to the dissolution of smell consciousness and the perception aggregate (samjna skandha). Further external signs are that one cannot digest food or drink, and t one cannot be aware of the names or affairs of close persons. Internal signs are the appearance of fireflies or sparks within the smoke. Then the fire element dissolves into the air element, and it becomes harder and harder to breathe. This corresponds to the dissolution of taste consciousness and the intellect aggregate (samskara skandha). External signs are the tongue becomes thick and short, and the mind becomes bewildered, unaware of the outside world. Then, mind consciousness and the consciousness aggregate (visjnana skandha) dissolve, and the patient stops breathing completely at this stage.

The patient is declared clinically dead, but in the Buddhist view, the subtle consciousness may still remain in the body for about three days. Therefore, the body is not to be touched or moved since this might disturb how the consciousness leaves the body and thus affect rebirth. In this way, one would think that Tibetans are very against organ transplant as it would appear to violate the consciousness still within the person’s body. However, according to Sogyal Rinpoche who posed this question to some high level masters, organ transplant, if done by the will of the donor, actually brings great merit to the consciousness, even if the operation disturbs it, because it is done with the mind of compassion for others. In general, though, one should wait for a monk to arrive to help with this transference of consciousness, so this becomes very difficult in people who die in the hospital. It is especially difficult for a priest to meditate and do anything in the hospital. Further, the effect of the medicine on the dying person has a strong effect on the consciousness and its ability to leave the body.

It is believed that the dead have wisdom and sensitivity nine times that of a regular person, so the thoughts and effects of the living have a huge effect on the dead soul. Therefore, showing strong remorse as the person dies and afterward is not good because it may engender attachment by the dying not to leave this life and disturb them from concentrating on the Buddha. Showing such remorse may still occur in Ladakh, but we are trying to change this and teach people to do their best to support the dying person’s journey onward.

For a typical person, the monk will perform a ritual called the Transference of Consciousness or phowa. From a Japanese Pure Land standpoint, this is basically the same as doing the visualized nenbutsu as explained in the Meditation Sutra (kanmuryoju-kyo), except that it is done on behalf of another person by the monk. In short, the monk does this visualization of Amida, calling him from the Pure Land and connecting him with the consciousness of the deceased person. Through this mediation, the person is able to finally exit their body and achieve Birth in Amida’s Pure Land. This practice, however, is for the ordinary, untrained person. A highly developed practitioner can do this visualization on their own and achieve this phowa through their own power. When an accomplished master dies in this way, the Tibetan tradition speaks directly of them attaining a rainbow body of light and of other omens which are very similar to the ones that accompanied Honen and many of his followers at their death, as related in the the Pictorial Biography of Honen Shonin (Honen Shonin gyojoezu/ Shijuhachikan-den).

In general, an astrologer is immediately consulted after the person's death to create the plan for the family to proceed with the funeral and the sort of rites they need to do to help their family member. As in Japanese Buddhism, there is the custom to do prayers and services for the 49 days that the consciousness takes to go through the intermediate bardo state. However, if the phowa transference of consciousness practice is performed properly, as if the nenbutsu is chanted properly in Japan, then the person gains immediate Birth in the Pure Land. In this case, these 49 day practices are more custom and bearing witness to the person’s death.

In general, nuns were not recognized or accepted in Ladakh until very recently. Ladakhi nuns have almost always lived with their parents and acted as servants for the whole family. When their parents die, they often lose any favourable conditions for their lives and continue to labor for the larger family. In general, we are grateful to receive the precept lineage from the old nuns, but we also want to do new things. We want to live together as a community of study and practice and not stay in our family homes. We want to get a formal education and serve society. One of the best ways to serve society is for us to also train as doctors, and by combining our medical and spiritual practice, serve the dying.

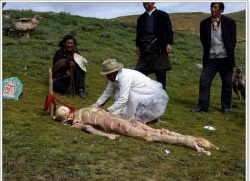

It is very interesting to see people dying. We work very hard to transform the severe pain of the sick person. Especially when the person is possessed by a spirit, our work can cure quite quickly. However, it is very important to build the personal connection with the patient. In order to do so, we have to go into their place and feel their pain. Some people who we treat are not Buddhists. Since they don’t believe in Buddhism, they can’t do the prescribed rituals. Even so, a dying person will feel comforted when they see a monk or nun appear, and some Muslims in our area may secretly apply some teachings to help themselves.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead tends to be only read when people have died, but we want to train the people before they die. It is considered a bad omen to read and study the Tibetan Book of the Dead before death, but we have a teaching and training program led by good teachers. They teach each page in detail, explaining how the whole practice works in particular. The important thing is to support people to change their lifestyle; for example, a nasty person can learn about their post-death fate that awaits and then begin to change.

In conclusion, Dr. Palmo emphasized that we really need to think about dying three times a day, so that we are prepared and able to control the mind while dying, and not just depend on machines to sustain our bodies. In Tibetan Buddhism, they also believe that the Pure Land is a permanent and real place from which we do not return. However, her group of nuns who are training to become doctors have the vow to come back to this world to help people, just like the Pure Land idea of going to and returning from the Pure Land (oso-genso).

References:

Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying (HarperSanFrancisco, 1994).

Lati Rinbochay & Jeffrey Hopkins, Death, Intermediate State and Rebirth in Tibetan Buddhism (Snow Lion Publications, 1985)