Manual of Pramana - Reading Ten: The Concept of Time

Selection from the collected topics:

The Concept of Time

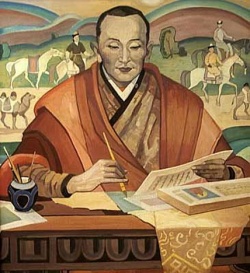

The following selections on the concept of time (Dus-gsum gyi rnam-bzhag), are excerpted from The Collected Topics of Rato (Rva-stod bsdus-grva), by Master Chokhla U-ser, a great master of Rato Monastery who lived about 1500 AD. This particular book is considered the “grandfather” of what came to be a separate genre of literature in Tibet: the dura (bsdus-grva), or “selected topics from the Commentary on Valid Perception (Pramana Varttika, or Tsad-ma rnam-’grel) of Master Dharmakirti (circa 650 AD).

Please note that indented statements are usually those given by the opponent. Responses within brackets are those that are usually left unwritten in the Tibetan text, and are understood to be there because of the context following each.

_______________

Suppose someone comes again, and makes the following claim:

The definition of the past is: “That which has begun and stopped.” The definition of the present is: “That which has begun and not yet stopped.” The definition of the future is: “That condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present.”

Respective examples would be the following. For the first, the example would be last year’s crops. For the second, it would be this year’s crops; and, for the third, crops soon to grow.

Concerning the first of these, we answer as follows.

Aren’t your definition and example for the past though incorrect?

Because there is no definition for the past,

And this is because the past doesn’t even exist,

And this is because anything which can be established as existing is always something of the present.

On this point, someone may come and make the following claim:

But there must be things that are past,

And this is because all three—past time, and future time, and present time—exist.

And this is because the three times exist.

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

And we also ask this person,

You already agreed to the reason here.

[Then I agree to your original statement: the past is the past.]

Suppose you agree to our original statement.

Consider the past.

It is not so the past,

Because it is not something which has stopped;

And this is true because it is not something which has been destroyed.

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

But it does necessarily follow,

Because “the past,” “that which has stopped,” and “that which has been destroyed” all refer to the same thing.

And this is true because all three of them exist;

And this is true because the past exists.

You already agreed that the reason is true.

Suppose that, instead of “it doesn’t necessarily follow,” the opponent says “it’s incorrect.”

Consider the past.

It is not so something which has been destroyed,

Because it is a working thing.

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

But it does necessarily follow,

Because there exists no one thing which is both (1) something that has been destroyed but which is still (2) a working thing.

And this is true because the Golden Necklace of Good Explanation says,

None of the schools that belong to the side that believe that things exist through some nature of their own accept the idea that something which has been destroyed could be a working thing.

[The Golden Necklace is a famed commentary by Je Tsongkapa upon the Ornament of Realizations, spoken to the realized being Asanga by Lord Maitreya.]

[Then I disagree to your earlier statement.]

Suppose you say that the earlier one is not correct.

Consider the past.

It is so a working thing,

Because it is something made.

[It's not correct to say that the past is something made.]

Suppose you say that it’s not correct.

Consider this same thing.

It is so,

Because it’s something that started.

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

But it does necessarily follow,

Because “something that started” is the definition of “something made.”

[The earlier point is not correct.]

Suppose you say that the earlier point is not correct.

Consider the past.

It is so something that started,

Because it is something that started and then stopped.

And this is true because it’s the past.

You’ve agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so, and the necessity is something that does apply to the definition. It must moreover be true that that which has been destroyed is a working thing,

Because the past is a working thing.

We’ve already established that the reason is true.

Suppose you do agree.

Is it then the case that a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing?

Because (1) there does exist a working thing which has been destroyed, and (2) that which has been destroyed is a working thing.

You’ve already agreed to the latter part of the reason.

Suppose now you say that the first part is not correct.

The first is too correct,

Because there does exist a working thing which is past.

[It's not correct to say that there does exist a working thing which is past.]

Suppose you say that it’s not correct.

Consider a working thing.

Because it is something that has been produced.

[Then I agree to your second original statement: it is the case that a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing.]

Suppose you agree to our second original statement.

So is a tree that was already destroyed still a tree?

Because a working thing which has been destroyed is still a working thing.

You’ve already accepted the reason.

[Then I agree to your original statement: a tree that was already destroyed is still a tree.]

Suppose you agree to our original statement.

So is it then true that when a tree has been burned up by fire there is still a tree?

Because (1) a tree that was already destroyed is a tree; and (2) there exists a destroyed tree subsequent to the burning up of a tree by a fire.

And this is so because—when a tree has been burned up by fire—there is a tree destroyed.

[I agree to your statement above.]

Suppose you agree to our statement above.

Is it then the case that—subsequent to the burning up of a tree by a fire—you can still see a tree by using your visual consciousness?

Because there does exist a tree subsequent to that point.

You already agreed to the reason.

If the one is the case, then the other is necessarily so. [That is, if there does exist a tree subsequent to that point, then you must be able to see it by using your visual consciousness.]

And you cannot agree to this last statement;

Because the following quotation from the Commentary on Valid Perception was meant to point out—to those who asserted that something which was destroyed could ever be a working thing—what very absurd consequences their position entailed:

Because it has started, then the destruction

Must be destroyed; and then the tree

Would have to be seen once more.

Concerning the second of the original definitions, [that the definition of the present is "that which has begun and not yet stopped,"] we pose the following:

Consider “knowable things.”

So is it something which has begun and not yet stopped?

Because it is something of the present.

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

But you already agree that it does necessarily follow.

[It's not correct to say that "knowable things" is something of the present.]

It is so correct,

Because it can be established as existing.

[Then I agree to your statement above: "knowable things" is something that has begun and not yet stopped.]

Suppose you agree to our statement above.

Consider “knowable things.”

So is it something which ever began?

Because it has begun and not yet stopped.

You already agreed to the reason.

[Then I agree to your statement.]

Suppose you agree to our statement.

Consider this same thing..

It is not so, that it is something which ever began,

Because it is an unchanging thing.

If you agreed [that an unchanging thing could begin], then what we would answer to you is obvious.

Concerning the third of the original definitions, [that the definition of the future is: "that condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present,"] we pose the following:

So is it true then that the future exists?

Because it is something which has a definition;

Because “that condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present” is the definition of the future.

You already agreed that the reason was true.

[Then I agree to your point above.]

Suppose you agree to the above.

So is it then the case that the future is itself?

Because it does exist.

[I agree to your statement: the future is itself.]

Suppose you agree to our original statement.

Consider the future.

So is it then a condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present?

Because it is the future.

You already agreed to the reason,

And it is obvious that the necessity must apply to the definition.

[Then I agree.]

Suppose you agree.

Depending on how they read this definition [in the Tibetan), some people claim, “I agree that the future is the condition of having not yet begun, although the causes for beginning are present (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).” Others claim, “I agree that the object of our argument [the future] is the condition of having not yet begun, even though it has cause to begin from this same condition (Tib: skye ba’i rgyu yod).”

Well suppose then that you read it the first way.

So does there exist a cause that makes the future begin?

Because the future is the condition of having not yet begun, even though the causes for beginning are present.

You’ve already accepted the reason.

[I agree that there does exist a cause that makes the future begin.]

Suppose you agree.

So is this cause that makes the future begin a working thing?

Because it does exist.

[I agree that it is.]

Suppose you agree.

Consider this cause that makes the future begin.

Is it something made?

Because it is a working thing.

[I agree that it is a working thing.]

Suppose you agree.

Consider this same thing.

Is it then something which has begun?

Because it is something made.

You already agreed to the reason.

But you cannot agree,

Because it is something which has not yet begun;

Because it is the condition of having not yet begun;

Because it is a condition where, even though [its cause) exists, it has not yet begun.

You’ve already agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so.

And the following problem applies to the latter way of reading the phrase.

Is it then the case that this cause that will make it begin is a working thing?

Because the cause that will make the future begin exists.

[It's not correct to say that the cause that will make the future begin exists.]

Suppose you say that it’s not correct.

Consider this cause that will make the future begin.

It does so exist,

Because [the future] is a condition where, even though [its cause exists), it has not yet begun.

You’ve already agreed both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so.

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

If you say it doesn’t necessarily follow, then your whole presentation collapses.

[Then I agree to your statement above.]

Suppose you agree to our statement above.

Consider the cause that makes [the future] begin.

It must then be something which has begun,

Because it is a working thing.

[I agree that the cause that makes the future begin is something which has begun.]

Suppose you agree.

Consider then this same thing.

It is not the case that it has already begun,

Because it is a thing which has yet to begin,

Because it is a condition of not having yet begun.

[It's not correct to say that the cause which makes the future begin is a condition of not having yet begun.]

Suppose you say that it’s not correct.

Consider this cause that makes the future begin.

It is so the condition of not having yet begun,

Because it is the condition of having not yet begun, even though it exists.

You’ve already both to the reason and to what we’re asserting must be so.

_______________

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

Does there exist a cause for something to begin or not?

We answer that there does, and then someone comes and makes the following claim:

But isn’t it the case that no cause for something to begin exists?

Because isn’t it the case that nothing beginning exists?

Because isn’t it the case that, if something is a working thing, it can never be beginning?

Because (1) isn’t it the case that, if something is a working thing, it must be something that began already; and (2) isn’t it the case that, if a working thing has begun already, it cannot start all over again?

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

_______________

Suppose someone comes again and claims,

So is it then the case that there are no beginnings at all?

Because none of the following exist: “something that’s going to begin,” “something that needs to begin,” “something that’s about to begin,” and “something that’s in the act of beginning.”

To this we say, “It doesn’t necessarily follow,” and then we say:

It’s like this. The beginning or the birth of something does too exist,

Because past and future births exist.

And this is true because there exists the practice of amassing the two collections over a great many births, past and future.

And this is true because there does exist the creation of an Infallible

Being, who comes from the practice of amassing the two collections over a great many births, past and future.

And this itself is true, because there is a point to the following two quotations:

By relying on the various proofs

It’s right to say “infallible.”

And—

The proof is that it comes from the practice

Of the attitude of compassion.

[Both quotations are from the Commentary on Valid Perception, and are used to establish that an Enlightened Being is produced from many eons spent amassing the two collections.]

Are you saying, moreover, that it is proper to throw away the whole system of those Lords of Reasoning, the Father and his spiritual Sons, and go following the system of that non-Buddhist school, the Rejectionists (Lokayata)?

Because you would have to accept the other side as our side in the following verses:

“An Infallible One would have to know

Even things that are hidden, and there’s

No proof that shows he can;

Neither is there a way to try.”

Thus do a number of them

Make their presentation.

And—

Because the mind is something

That depends upon the body,

There is nothing you can achieve

Through practice [over many lifetimes].

And this is true because it would then be right for you to accept the position that it’s impossible for there to exist an enlightened realized being who has practiced assembling the two collections over a great many births, past and future.

_______________

Suppose someone comes again and claims,

There must too exist a working thing which is about to begin,

Because there exists a working thing which is about to take birth from their mother’s womb.

So does there exist then a working thing which is in the act of beginning?

Because there exists a working which is about to take birth from their mother’s womb.

The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable.

But you cannot agree, because the glorious Chandrakirti has stated, “Since something in the act of beginning is only approaching beginning, it is not something which exists.”

And are you, furthermore, saying that there exists a working thing which hasn’t begun?

Because there exists a working thing which hasn’t begun, from their mother’s womb.

Suppose someone comes and says, “It’s incorrect [to say that there exists a working thing which hasn't begun, from their mother's womb).

But it is correct, because (1) there does exist a person who is in the act of staying in their mother’s womb, and (2) there also exists a working thing which is born complete.

Are you saying, moreover, that a working thing which has already begun begins again?

Because there exists a living being who has already taken birth, and who has to take birth again.

And this is true because there exists a living being who has already taken birth, and who has to take birth again in the circle of suffering life.

And this is true because (1) there exists a living being who has already taken birth as a human, and who has to take birth again as a human; and (2) there exists a living being who has already taken birth into the desire realm, and who has to take birth into the desire realm again.

Each of the reasons given is correct, because there do exist those who come from a birth as a human and are born as a human; and there do exist those who come from a birth in the desire realm and are born into the desire realm. It’s easy to accept these reasons.

And is it, moreover, the case that there exists nothing which is occurring?

Because nothing which is a working thing could ever be something which is occurring.

And this is because anything which is a working thing is something which has already occurred.

The fact that it follows is something you find acceptable.

The reason we’ve stated is correct, because anything which is a working thing is something which has already occurred from its own causes.

And this is true because anything which is a working thing is something which has already begun from its own causes.

[Then I agree to your original statement: it is the case that there exists nothing which is occurring.]

Suppose you agree to our original statement.

There does too exist something which is occurring,

Because there exist the four great elements.

And this is because there do exist the four of earth, water, fire, and wind.

[Translator's note: This argument depends upon the fact that the Tibetan words for "occurring" and for "element" have the same spelling ('byung ba).]

[It doesn't necessarily follow.]

It does necessarily follow, because that highest master, Vasubandhu, has stated that the great elements are four.

And this is true because the Treasure House says,

The elements are the following:

The divisions of elements we call

Earth and water and fire and wind.

_______________

Suppose yet another person comes and claims:

There must too exist a working thing which still has to start,

Because there does exist a working thing which is going to start.

And this is because there does exist a working thing which is going to occur.

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

The reason in itself though does apply to the subject,

Because the four of blue, yellow, white, and red and the like are all derivatives of the elements, and there also exist tangible objects which are derivatives of the elements.

And this is true because all tangible objects can be divided into two types: those that are elements, and those that are derivatives of the elements.

[Translator's note: This argument depends on the fact that the Tibetan for "going to occur" and for "derivative of the elements" is the same ('byung-'gyur).]

And this is true because The Treasure House of Wisdom says,

Tangible objects are of two types…

You can’t though agree to the original statement, [that there must exist a working thing which still has to start],

Because anything which is a working thing is something which must have already started.

On this point some may make the following claim:

It must so be the case that there exists no working thing which is going to occur,

Because anything which is a working thing must have already occurred.

This position though reflects a gross error of failing to examine things thoroughly. The expressions “going to start” and “still needs to start” are equivalent in meaning, exclusively, “going to start from the beginning” and “still needs to start from the beginning.”

But whereas “still needs to occur” means, exclusively, “still needs to occur from the beginning,” the (Tibetan phrase for] “going to occur” also applies to things which have already occurred, such as the color blue, or the tangible objects of heat or cold, and so on. And the mistake by the opponent here is that they have never heard the terms explained this way.

_______________

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

The definition of something “past” relative to the time of a water pitcher is “that which has started and also stopped, in the time that the water pitcher is present.”

The definition of something “future” relative to the time of a water pitcher is “that which is such that—although the causes for it to start are already present—it has yet to start, in the time that the water pitcher is present.”

The definition of something “present” relative to the time of a water pitcher is “that which has started and not yet stopped, in the time that the water pitcher is present.”

Let us address the first of these definitions.

Consider the cause of a water pitcher.

Is this cause then something which has started and also stopped, in the time that the water pitcher is present?

Because it is something which is past relative to the time of the water pitcher.

And this is because it is the example we’ve chosen here.

And suppose you agree to the previous statement. [That is, suppose you agree that the cause of a water pitcher is something which has started and also stopped in the time of the water pitcher.]

Consider again the cause of a water pitcher.

Is it then one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher and (2) stopped in the time of the water pitcher?

[Why do you say that?]

Because you agreed.

[Then I agree that the cause of a water pitcher is one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher and (2) stopped in the time of the water pitcher.]

Suppose you agree then.

Consider this same thing.

Is it then something which has started in the time of the water pitcher?

[Why do you say that?]

Because you agreed above.

And yet you can’t agree, because it is something which has not started in the time of the water pitcher.

And this is because it is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher.

[It's not necessarily the case that, because the cause of a pitcher is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher, it must be something which has not started in the time of the water pitcher.]

Suppose you say that it’s not necessarily the case.

It is though necessarily the case,

Because the very definition of something’s not having been made in a certain time is “something’s not having started” in that same time.

And this is true because (1) there is at that time something which hasn’t been made, and (2) the definition of “something that hasn’t been made” is “something that hasn’t started.”

And this is true because “something that has started” is the definition of “something that has been made.”

Now suppose that you were to answer “it’s not correct to say that” above, where you answered “it doesn’t’ necessarily follow.” [That is, suppose you say that it's not correct to say that the cause of a water pitcher is something which has not been made in the time of the water pitcher.]

Consider this same thing.

It is so true that it has not been made in that particular time,

Because it doesn’t even exist in that particular time.

And this is because it has stopped in that particular time.

And this is because, in that particular time, it has started and also stopped.

And you’ve already agreed to what we stated as our reason.

Consider, moreover, the cause of a water pitcher, once again.

It is not so, that it is one thing which has both (1) started in the time of the water pitcher, and (2) stopped in this same time,

Because it is not something which has stopped.

And this is true because it hasn’t stopped.

And this is true because it is a produced thing.

_______________

Suppose yet another person comes, and makes this claim:

Consider the cause of a water pitcher.

It is too something which has started in the time of the water pitcher,

Because it has finished starting in the time of the water pitcher.

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

Therefore we have to express the situation as follows: Although the cause of the water pitcher, in the time of the water pitcher, has already begun, it is not something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher. This is for example like the case where the followers of the Independent group of the Middle-Way School and such say that “Cause and effect is true [Tib: bden-pa], but not real [Tib: bden-pa].” You have to be able to make the same kind of distinction here.

____________

Suppose someone comes along and claims,

Even though omniscience perceives a water pitcher directly, it does not do so in the sense that the word “directly” has when we divide perception into the two of “direct” and “deductive.”

To this we answer, “You are absolutely correct.”

If however someone were to come along in a debate and say that “Every state of direct perception is ‘direct’ in the sense that this word has when we divide perception into the two of ‘direct’ and ‘deductive’,” some logic would be required to prove the point just made.

____________

As for the second definition, [the definition of "the future" given above,] consider the result of a water pitcher.

Is it then something that has not begun?

Because it is the condition of not having begun.

And this is because it is the condition of not having begun, even though the causes for its beginning exist in the time of the water pitcher.

Now some may come along and claim, in response, that “it doesn’t necessarily follow.” This however would indicate that they had yet to grasp the meaning of the collected topics on logic and perception.

Suppose someone else came and said, instead, that “Your reason is not correct.”

Consider then this same thing: [the result of a water pitcher].

Are you saying that it is the condition of not having begun, even though, in the time of the pitcher, the causes for its beginning are present? Because it is “the future” at this same time.

The correctness of our reason is easy to accept.

And you’ve already accepted the necessity.

As for the third of the definitions above, [that of "the present,"] suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

Consider the cause of a water pitcher.

It is so something which is present-time in the time of the water pitcher,

Because it is something which, in the time of the water pitcher, has begun and not yet stopped.

It is so, because it is both (1) something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher and (2) something which has not stopped in that time.

Our side would answer that the first part of this reason is not correct.

And then the other side would come back with,

Consider then this same thing.

It is too something which has begun in the time of the water pitcher,

Because it is something which has finished beginning in that time.

To this we’d answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

Here next is an analysis of the question of whether the past and the future exist or not. Generally speaking there exist no definitions for “the past” or “the future,” because the past and future are not things which even exist. This is because, anything which can be established as existing must always be existing in the present [according to this school of Buddhism).

If though we were to establish the meaning of “the past” relative to a specific point of reference, we could say that the definition of its past relative to the time of a specific water pitcher could be given as follows:

Something which has, by the time of the water pitcher, already started; and which has, by the time of the water pitcher, already ended as well.

This and “the pitcher just before the pitcher” amount to the same thing.

The definition of its present relative to the time of a specific water pitcher then could be given as follows:

That one thing which is both (1) something which has already come into existence by the time of the water pitcher; and (2) which is simultaneous to the water pitcher.

The definition of its future relative to the time of a specific water pitcher, finally, could be given as follows:

That one thing which is both (1) in the act of starting at the time of the water pitcher; and (2) not yet started at the time of the water pitcher.

The following all amount to the same thing:

the not-yet-coming of the water pitcher;

the cause of the water pitcher;

its past at the time of the water pitcher; and

its past relative to the water pitcher.

[Translator's note: "Not-yet-coming" and "future" are the same word in Tibetan (ma- 'ongs-pa).]

The following also all amount to the same thing:

the passing of the water pitcher;

the result of the water pitcher;

its future at the time of the water pitcher; and

its future relative to the water pitcher.

[Translator's note: "Passing" and "past" are the same word in Tibetan ('das-pa).]

Generally speaking, there is no such thing as something which has stopped.

And there is nothing which is about to begin. Neither is there anything which is in the act of beginning, nor is there anything which is approaching the state of beginning.

There does exist though the passing of the smoke; and the stopping of the smoke; and the smoke’s not yet coming, and the smoke’s being about to begin; and the smoke’s being in the act of beginning; and the smoke’s approaching the state of beginning.

There is though no such thing as smoke which is approaching the state of beginning. Neither is there any smoke which is in the act of beginning; nor any smoke which is about to begin; nor smoke which has stopped; nor smoke which has been destroyed; nor smoke which is past; nor smoke which is future.

The following all amount to the same thing:

a working thing;

a changing thing;

a momentary thing;

a thing which is in the act of being destroyed;

a thing which is approaching the past;

a thing which is approaching its destruction.

These assertions [about the nature of time) are all presented in accordance with the beliefs of the “Logician” group within the Sutrist School. They would not necessarily be acceptable to any other school of Buddhism. The Detailists, for example, do accept ideas such as past karma and future karma, while the Necessity group entertains unimaginably profound positions such as the one that states that the destruction of something is a working thing.

A Discussion of Incorrect Logical Statements

The following presentation on incorrect “logical” statements is excerpted from An Explanation of the Art of Reasoning (rTags-rigs), by the Tutor of His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Purbuchok Jampa Tsultrim Gyatso (1825-1901).

_______________

Here is the second major division of our presentation, in which we explain the opposite of a correct reason: that is, incorrect reasons. We proceed in two steps: the definition of such reasons, and their various divisions.

The first of these we’ll discuss in terms of disproving our opponent’s beliefs, and then establishing our own beliefs. Here is the first. Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim: “Any reason where the three relationships fail to hold” is the definition of an incorrect reason.

This though is mistaken, for there is no such thing as an incorrect reason: everything which exists is a correct reason [to prove something].

Here secondly is our own position. The definition of an incorrect reason for a particular proof is:

A reason for a particular proof where the three relationships fail to hold.

Here secondly are the various divisions of incorrect reasons. Although there is not, generally speaking, any such thing as an incorrect reason, we can say that there do exist the following types of incorrect reasons in specific contexts:

1) Contradictory reasons for specific proofs;

2) Indefinite reasons for specific proofs; and

3) Wrong reasons for specific proofs.

We will discuss the first of these in four steps: definition; divisions; classical examples; and supporting arguments.

Here is the first. The definition of a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing is:

That one thing for which (1) the relationship between the subject and the reason does hold for proving that sound is an unchanging thing; and (2) the positive necessity between the reason and the quality to be proven also holds for proving that sound is not an unchanging thing.

[A classical example would be: Consider sound. It is an unchanging thing, because it is a made thing.]

Here secondly are the divisions.

Contradictory reasons can be divided into two kinds: those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, and those which have a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, [covering or not].

Here thirdly are the classical examples. “Something that was made” is a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing. “Something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’” is a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in proving the same thing.

Next is the fourth category: the supporting arguments.

Consider “something that was made.”

It is so a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they cover it completely, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing,

Because it is both (1) a contradictory reason for proving this particular thing, and (2) anything which is changing is also it.

And consider “something which is a particular example of the general type called ‘made things’.”

It is so a contradictory reason which has a relationship with the group of dissimilar cases where they go both ways, in a proof that sound is not a changing thing,

Because it is a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing.

And this is so because (1) the relationship between this reason and the subject of the particular proof holds; and (2) it is definitely the case that the positive necessity between it and the quality to be proven is diametrically false.

Consider, moreover, this same example.

It is so a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing,

Because it is a correct reason for proving that sound is a changing thing.

_______________

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

So does there exist then a contradictory reason for proving that sound is a changing thing?

Because there does exist a contradictory reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing.

To this we answer, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

And you could never agree [that there did exist a contradictory reason for proving that sound is a changing thing],

Because anything which is an incorrect reason for proving that sound is a changing thing must be either (1) an indefinite reason for the particular proof or (2) a wrong reason for the particular proof.

____________

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

If there exist the three relationships for any particular proof, then there must exist a correct reason for the particular proof.

Consider all knowable things.

There must then exist a correct reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing,

Because the three relationships do exist for proving that sound is an unchanging thing.

You’ve already accepted that it necessarily follows.

Suppose then that you say that it’s not correct [that the three relationships do exist for proving that sound is an unchanging thing].

They do too exist, because (1) there exists a relationship between the reason and the subject for this particular proof, and (2) there exists the positive necessity for the proof, and there exists the reverse necessity for the proof.

The first part of our reason here is correct, because the relationship between the reason and the subject holds when “something made” is used as the reason in a proof that sound is an unchanging thing.

Suppose you say that it’s not correct [that the relationship between the reason and the subject holds when "something made" is used as the reason in a proof that sound is an unchanging thing].

Consider this same thing [that is, "something made"].

The relationship does too hold with it,

Because it is a contradictory reason for the particular proof.

And that’s true because it is a correct reason for proving that sound is a changing thing.

And the second reason is a correct one, because that one thing which is both an existing phenomenon and something which is not momentary satisfies the positive necessity in a proof that sound is an unchanging thing.

Suppose you say that this is not correct.

Consider this same thing [that one thing which is both an existing phenomenon and something which is not momentary].

It does too [satisfy the relationship of positive necessity],

Because (1) there does exist a correct similar example which covers both the reason and the quality to be proven, in this particular proof where that “one thing” we mentioned is used as the reason; and (2) this “one thing” can be verified, through a valid perception, as something that fits only the group of similar cases, in the way it is stated, within a proof that sound is an unchanging thing.

Now the first part of our reason is correct, because “unproduced, empty space” would be a correct similar example which covers both the reason and the quality to be proven in this particular proof, where the “one thing” we mentioned is used as a reason.

And the second part of our reason is correct, because “that one thing which is both an existing phenomenon and something which is not momentary” is something that fits only the group of similar cases, in the way it is stated, within this particular proof.

And this is because it is, in fact, the definition of something which is unchanging.

The third part of our reason above, [that there exists the reverse necessity for the proof,] is also correct. This is because that one thing which is both (1) an existing phenomenon and (2) something which is not momentary fulfils that same necessity.

Now suppose you say that our last reason is not correct. Consider this same thing [that is, that one thing which is both (1) an existing phenomenon and (2) something which is not momentary].

It does so fulfil the reverse necessity for the proof that sound is an unchanging thing,

Because there does exist a correct dissimilar example for the proof in which it serves as the reason; that is, an example which possesses neither the reason nor the quality to be proven for the particular proof. And it can also be verified, through a valid perception, that it only does not fit the group of dissimilar cases for the proof.

Suppose finally that you agree to the original statement: [that is, you agree that there must exist a correct reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing].

Consider then sound.

It is rather so, that there exists no correct reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing;

Because it is not something which is unchanging.

_______________

Suppose someone comes and makes the following claim:

It must then be so, that there is something for which all three relationships hold, in proving that sound is an unchanging thing;

Because there is something which fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for this proof; and there is something which fulfils the positive necessity for the proof; and there is something which fulfils the reverse necessity for the proof.

To this we reply, “It doesn’t necessarily follow.”

____________

Here secondly is our explanation of an indefinite reason; we will proceed first with a definition, and then with the various divisions of this reason. Here is the first of these.

The following is the definition of an indefinite reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing:

That one thing for which (1) the relationship between the subject and the reason for proving that sound is an unchanging thing does hold; (2) the reverse relationship between the reason and the subject for proving that sound is an unchanging thing does not hold; and (3) the reverse relationship between the reason and the subject for proving that sound is not an unchanging thing doesn’t hold either.

[A classical example would be: Consider sound. It is an unchanging thing, because there is no such thing as antlers on a rabbit's head.]

Here secondly are the divisions. This kind of reason can be divided into two: unique indefinite reasons for a particular proof, and common indefinite reasons for a particular proof. We will discuss the first of these two in two steps: its definition, and a classical example for it.

Here is the first. The definition of something which is a unique indefinite reason for a particular proof is:

That one thing which is both (1) an indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has yet to verify either one of the following: that it fits the group of similar cases for the proof, or that it fits the group of dissimilar cases for the proof.

Here secondly are some classical examples.

The following are all both unique indefinite reasons for proving that sound is an unchanging thing, and unique indefinite reasons for proving that sound is a changing thing:

something you can hear;

the reverse of all that is not sound; and

We will discuss the second type, common indefinite reasons, in two steps as well: definition, and divisions. Here is the first.

The definition of a common indefinite reason is:

That one thing which is both (1) an indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has either verified (a) that it fits the group of similar cases for the proof, or (b) that it fits the group of dissimilar cases for the proof.

Here is the second. These types of reasons may be divided into three: those which are direct indefinite reasons for a particular proof; those which are uncertain indefinite reasons for a particular proof; and those indefinite reasons which are neither of the first two. Again we will discuss the first of these in terms of its definition and its divisions.

Here is the first. The definition of something which is a direct indefinite reason is:

That one thing which is both (1) an indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has verified that it fits both the group of similar cases and the group of dissimilar cases for the proof.

Here secondly are the divisions of this type of reason. They come in four different types:

1) Those direct indefinite reasons that cover both the group of similar cases and the group of dissimilar cases for the particular proof;

2) Those same kinds of reasons that cover the group of similar cases for the particular proof, but which go both ways as far as its group of dissimilar cases;

3) Those same kinds of reasons that cover the group of dissimilar cases for the particular proof, but which go both ways as far as its group of similar cases; and

4) Those same kinds of reasons that go both ways as far as both the group of dissimilar cases and the group of similar cases for the particular proof.

Here are respective classical examples for each of these types.

1) The fact that there are no such things as rabbit antlers would be a direct indefinite reason that covers both the group of similar cases in a proof that sound is an unchanging thing, and the group of dissimilar cases for this same proof.

2) “Changing thing” would be a direct indefinite reason that covers the group of similar cases in a proof that the sound of a conch shell is something produced through a conscious effort, but which goes both ways as far as the group of dissimilar cases for this same proof.

3) “Changing thing” would be a direct indefinite reason that covers the group of dissimilar cases in a proof that sound of a conch shell is not something produced through a conscious effort, but which goes both ways as far as its group of similar cases.

4) “Sense consciousness” would be a direct indefinite reason that goes both ways as far as both the group of dissimilar cases and the group of similar cases in a proof that a sense consciousness which thinks there are two moons [where there is only one] is a direct [valid] perception.

Here secondly is our discussion of uncertain indefinite reasons; we will repeat the two steps of their definition and their divisions. Here is the first.

The definition of something’s being an uncertain indefinite reason for a particular proof is the following:

That one thing which is both (1) a common indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has either (a) already verified that it fits the group of similar cases for the proof, but is still uncertain whether it fits the group of dissimilar cases for the proof or not; or else (b) already verified that it does fit the group of dissimilar cases for the proof, but is still uncertain whether it fits the group of similar cases for the proof or not.

Here secondly are the divisions of this type of reason. There are two: correct uncertain indefinite reasons and contradictory uncertain indefinite reasons.

The definition of something’s being a correct uncertain indefinite reason for a particular proof is:

That one thing which is both (1) an uncertain indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has already verified that it fits the group of similar cases for the proof, but is still uncertain whether it fits the group of dissimilar cases for the proof or not.

The definition of something’s being a contradictory uncertain indefinite reason for a particular proof is:

That one thing which is both (1) an uncertain indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has already verified that it fits the group of dissimilar cases for the proof, but is still uncertain whether it fits the group of similar cases for the proof or not.

Here are some examples, in the order we gave the definitions. An example of the first would be giving “because he is making pronouncements” as a reason for proving that John, who is making pronouncements, is not an omniscient being—and giving this reason to someone who doubts the existence of an omniscient being.

The same reason presented to the same person to prove that John, who is making pronouncements, is an omniscient being would be an example of the second type.

Here thirdly we’ll explain those common indefinite reasons which are neither the direct nor uncertain types. Again we proceed in terms of definition and classical example.

Here is the first. The definition of something being a common indefinite reason which is neither the direct nor the uncertain types for a particular proof is:

That one thing which is both (1) a common indefinite reason for a particular proof; and (2) such that a person who already recognizes that it fulfils the relationship between the subject and the reason for the particular proof has already verified either that it fits only the group of similar cases for the proof, or that it only doesn’t fit the group of dissimilar cases for the proof.

Here secondly is our classical example. “[Because there is a] taste of sugar in the present time” is a common indefinite reason which is neither the direct nor the uncertain types in a proof that a lump of sugar in one’s mouth has the visible appearance of a lump of sugar in the present time.

Here third is our presentation on wrong reasons. Again we proceed in two steps of definition and divisions. Here is the first.

The definition of a wrong reason for any particular proof is:

That which (1) has been put forth as a reason for a particular proof, but (2) for which the relationship between the subject and the reason does not hold.

Here secondly are the divisions of wrong reasons for particular proofs. There are three different types:

1) Reasons which are wrong relative to meaning.

2) Reasons which are wrong relative to a state of mind.

3) Reasons which are wrong relative to the particular opponent.

The first of these may itself be divided into seven different types:

1) Reasons which are wrong because the very nature of the reason is non-existent.

2) Reasons which are wrong because the very nature of the subject is non-existent.

3) Reasons which are wrong because the reason and the quality to be proven are indistinguishable from one another.

4) Reasons which are wrong because the subject and the reason are indistinguishable from one another.

5) Reasons which are wrong because the subject and the quality to be proven are indistinguishable from one another.

6) Reasons which are wrong because the reason does not pertain to the subject in the way it has been said to in the statement of the proof.

7) Reasons which are wrong because some part of the reason fails to belong to the subject under consideration.

The following are respective examples of these types of reasons, in particular proofs:

1)

Consider a particular person.

They are a suffering being,

Because they have been impaled on a rabbit’s antlers.

2)

Consider the antlers on the head of a rabbit.

They are a changing thing,

Because they were made.

3)

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is a changing thing.

4)

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is sound.

5)

Consider sound.

It is sound,

Because it is something which was made.

6)

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is something that you see with your eyes.

7)

Consider a fruit tree.

It must be a conscious thing,

Because its leaves curl up and night and seem to sleep.

This brings us to the second kind of wrong reason: the one that is wrong relative to a state of mind. Here there are four different types:

1) Reasons that are wrong because the opponent entertains doubt about the very nature of the reason.

2) Reasons that are wrong because the opponent entertains doubt about the very nature of the subject.

3) Reasons that are wrong because the opponent entertains doubt about the connection between the subject and the reason.

4) Reasons that are wrong because there is nothing that the opponent has yet to understand.

The following are respective examples of these four, for particular proofs.

1) The following proof, presented to a person who has yet to confirm to himself that “flesh-eaters” [a kind of ghost) actually exist:

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because flesh-eaters are something which can be cognized through valid perception.

2) The following proof, presented to a person who has yet to confirm to himself that “smell-eaters” (spirits in the bardo or inbetween state) actually exist:

Consider the song of the smell-eaters.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is something that was made.

3) The following proof, presented to a person who doesn’t know where a particular peacock is:

Consider that mountain vale over there.

There must be a peacock living there,

Because we can hear a peacock crowing.

4) The following proof, presented to the glorious Dharmakirti:

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is something that was made.

Here thirdly is our explanation of reasons which are wrong relative to the particular opponent. There are three different kinds of these reasons:

1) Reasons which are wrong relative to the proponent.

2) Reasons which are wrong relative to the opponent.

3) Reasons which are wrong relative to both the opponent and the proponent.

Here are respective examples for these three types of reasons, in particular proofs.

1) The following proof, presented to a Buddhist by a Numerist [of member of the Sangkya, a non-Buddhist school of ancient India]:

Consider the intellect.

It is something devoid of mind,

Because it is something which starts and stops.

2) The following proof, presented to a Buddhist by a member of the Unclothed

[or Jain school of ancient India]:

Consider a fruit tree.

It must have a mind,

Because it dies when you peel its bark.

3) The following proof, presented to a member of the Rejectionist (Lokayata) school by one of the Unclothed (Jain) school [both non-Buddhist groups of ancient India]:

Consider sound.

It is a changing thing,

Because it is something you see with your eyes.

The traditional debate year

The following annual calendar for Sera Mey Tibetan Monastery gives a good picture of the schedule of study followed by all monks in the geshe program at the monastery. It is a traditional schedule which developed at the original Sera Mey in Lhasa, Tibet, over the centuries; since the rebuilding of Sera Mey in south India, the schedule has been reinstated—with a certain number of variations from the one used in Tibet—and is now followed closely, with some exceptions due to the need to work in the monastery cornfields and so on. Below is a translation of the annual calendar as it is currently posted on at the main temple of the monastery; the notes and some amendations to the calendar were completed with the help of Khen Rinpoche Geshe Lobsang Tharchin, a former abbot of the monastery.

_______________

Annual Calendar of Debates, Examinations, and Other Special Events at Sera Mey Tibetan Monastery Bylakuppe, South India Schedule of Regular Dharma Sessions

The following are the eight traditional “dharma sessions” (chos-thog) that make up the standard periods of monastic study at Sera Mey Monastery. The first Tibetan month, by the way, normally falls in February or March of the western calendar. The dates below are the same for any given year, independent of the day of the week, and follow the waxing and waning of the moon.

Session One: The Earlier Dharma Session of Spring (dPyid-chos dang-po)

Starting assembly: 26th of the first Tibetan month

First firewood break: 27th and 28th of the first Tibetan month

The “firewood break” (shing-slong), or literally “time for requesting firewood from sponsors” follows immediately after the starting assembly (yar-tsogs).

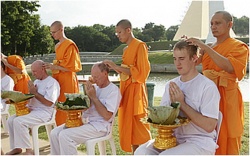

This assembly features prayers for the success of the session, and is attended by all monks who intend to participate for this period. It is also during this assembly that young monks who have been deemed ready by the abbot, the debate master, and their house teacher undergo the ceremony of intitiation into the debate park. These “newbies” are known as sarshuk (gsar-zhugs), or “newly entered.” They are expected to demonstrate their commitment to the debate session through perfect attendance, and especially serious study and debate, for the entire length of the session.

In Lhasa, a head-count was taken during the starting assembly in order to determine the cooking and other needs. During the next two days, teams of monks would go out to help find firewood for the monastery kitchen, based on the head-count.

The first day of the firewood break was devoted to visiting lay communities in the countryside outside of Lhasa city to ask for firewood; families in these villages knew what day to expect the monks, and considered it an honor to prepare a good supply of wood in advance. On the second day the monks would travel to Lhasa city proper to request fuel. This supply of wood would have to last about two weeks, until the “mid-term firewood break” (rked-pa’i shing-slong).

Great debate examinations: tsokrampa geshe examinations, 28th to the 30th of the first Tibetan month

During specific sessions, intense debate examinations are held for candidates standing for various degrees at the monastery. The most well known of these degree titles is the geshe. The word “geshe” (kalyaNa mitra in Sanskrit, or dge-bshes in Tibetan) literally means “spiritual friend,” and is a term from the earliest days of Buddhism in India. Later, great masters among the first Tibetan Buddhists—the Kadampas—were called “geshe” out of respect for their learning and high level of practice.

As monastic institutions began to form in Tibet, the word “geshe” came to be used as a title. It was originally used in the early “Big Three” monasteries of Sangpu (gSang-phu), Kyormo Lung (sKyor-mo lung), and Gadong (sGagdong). Sangpu, for example, was founded around the middle of the eleventh century.

Sangpu had two colleges within the confines (or gseb) of the monastery as a whole (known as the gling); early geshe candidates had to make their debate defense at a combined assembly of the two, and came to be known as lingse geshes, a corruption of the word lingsep (gling-gseb). The Great Dictionary of the Tibetan Language and other sources take the word lingse to mean gling-bsre, or a defense before the “combined” (bsre) assemblies of the two colleges in the monastery (gling). In either case, the point is the same.

At Sera Mey, there are typically four lingse geshe degrees conferred per year: these come in two pairs known as the “summer lingse” and the “winter lingse.” Geshes of this rank go through an examination process within their own monastery, as described in a previous reading for this course. During some of their defenses, these and other geshe candidates are required to provide an elaborate series of refreshments, involving some served to the entire assembly of their monastery. This ceremony is known as the “Thirteen-Course Tea and Broth” (Ja-thug bcu-gsum).

During other defenses, lingse candidates need only provide a series of ten tea offerings on the day when they undergo a special part of their examination which involves reciting a great many pages of scripture from memory. This test is called a geshe shepa (dge-bshes bshad-pa); and since the major refreshments of tea and broth are not served to the entire assembly this time, the presentation is known as a “dry recitation” (skam-bshad).

Below the rank of lingse geshe is the rikrampa (rigs rams-pa), and the next higher rank after the lingse is the tsokrampa (tsogs rams-pa). In both cases, the word rampa refers to the veritable myriad (rab-’byams, shortened to rams-pa) number of great Buddhist classics that a geshe must master. The word tsok in tsokrampa refers to the Session of the Great Assembly (Tsogschos), an annual meeting in Lhasa city of the six great colleges. Here there are two each for the “Great Three” monasteries of later times: Sera, Ganden, and Drepung, all founded around the opening of the fifteenth century. Representatives from Deyang (bDe-yangs) monastery would also attend this gathering, during which the candidates for the tsokrampa rank would have to defend their knowledge.

The Great Assembly traditionally began on the 20th of the second Tibetan month, and ended on the 30th. This is the time it would take to complete the examination of one or two tsokrampa candidates from each college per year. Candidates for the highest rank of geshe, the hlarampa (hla rams-pa), are examined during the Great Prayer Festival, or Munlam Chenmo. This festival was instituted by Je Tsongkapa in the 15th century as a great dharma celebration for the New Year. Since it was held in the capital city of Lhasa

(Hla-sa), these geshes became known as hlarampa. Each of the six colleges normally nominates two candidates per year for the rank of hlarampa, although on some occasions it may be as many as four.

First actual debate session: begins 1st of the second Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 5th and 6th of the second Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 7th of the second Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 18th of the second Tibetan month

The “Auspicious Conclusion” (Shis-brjod) is a day of prayer and celebration for the successful end of another dharma session; it is marked by special recitations known as “pronouncing” (brjod) the “auspiciousness” (bkra-shis, the “trashi” in “trashi delek”). These prayers are done in a unique melody or yang (dbyangs). On this day too, the abbot of the monastery will often deliver a special dharma teaching.

Intersession break (Chos-mtsams):

19th of the second Tibetan month to the 7th of the third Tibetan month

Session Two: The Great Dharma Session of Spring (dPyid-chos chen-mo)

Starting assembly: 8th of the third Tibetan month

First firewood break: 9th and 10th of the third Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: summer lingse geshes, 11th to the 12th of the third Tibetan month

First actual debate session: begins 13th of the third Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 22nd and 23rd of the third Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 24th of the third Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 7th of the fourth Tibetan month

Intersession break:

8th of the fourth Tibetan month to the 16th of the fourth

Tibetan month

Session Three: The Earlier Summer Dharma Session (dByar-chos dang-po)

Starting assembly: 17th of the fourth Tibetan month

First firewood break: 18th and 19th of the fourth Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: (no geshe debates)

First actual debate session: begins 20th of the fourth Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: (none)

Second actual debate session: (none)

Auspicious conclusion: 1st of the fifth Tibetan month

Intersession break: 2nd of the fifth Tibetan month to the 16th of the fifth Tibetan month

Session Four: The Great Dharma Session of Summer (dByar-chos chen-mo)

Starting assembly: 17th of the fifth Tibetan month

First firewood break: 18th and 19th of the fifth Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: summer lingse geshes (“dry recitation”) and rikram

geshes; 20th to the 23rd of the fifth Tibetan month

First actual debate session: begins 24th of the fifth Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 2nd and 3rd of the sixth Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 4th of the sixth Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 15th of the sixth Tibetan month

Intersession break:

16th of the sixth Tibetan month to the 16th of the seventh Tibetan month; includes rikram geshe exams, summer lingse geshe exams, rikchung pre-geshe exams, and rikdra inter-monastic debates

The rikdra (rigs-grva) inter-monastic debates begin on the last day of the sixth Tibetan month and last until the 15th day of the seventh Tibetan month. During this time, thirty debaters from Sera Mey debate with thirty counterparts from the sister monastery of Sera Jey in the main assembly hall (tsogs-chen) shared by both monasteries for major events such as the biweekly monks’ purification ceremony, or sojong (gso-sbyong).

During this time, pairs of debaters match off twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening, for fifteen days. In a typical session, the proponent (snga-rgol) will be responsible for a lengthy recitation of scripture from memory, after which his opponent (phyi-rgol) is charged with posing a difficult series of formalized debate questions. In Tibet, the combined monasteries of Sera Mey and Sera Jey had joint holdings of property, and the income from these would be used during this session to supply all the monks attending with gifts of Tibetan pastries (kabse) and roasted barley flour, or tsampa.

It is also during this time that the rikchen (rigs-chen), or advanced pre-geshe debates, are held. Here a student who intends to take a higher geshe degree engages in a difficult and highly formalized debate against a similar candidate from the sister monastery. Other students in the monastery during this time are engaged in special examinations, administered by the abbot and debate master of their home monastery, during which they are required to recite, from memory, about 100 pages of scripture.

Session Five: The Water Dharma Session (Chab-zhugs chos-thog)

Starting assembly: 17th of the seventh Tibetan month

First firewood break: 18th and 19th of the seventh Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: (no geshe debates)

First actual debate session: begins 20th of the seventh Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: (none)

Second actual debate session: (none)

Auspicious conclusion: 30th of the seventh Tibetan month

The “Water” Session (Chab-zhugs) is possibly given this name due to the fact that, during the period following the especially intense Great Session of Summer, students in the geshe program finally have enough time to relax and “enter the water” (chabzhugs), or take a nice slow bath. The rikchung and rikchen (preliminary and advanced pre-geshe debates) have been completed, as have the grueling rikdra intermonastic debates, and memorization exams. Students would be allowed take breaks in special parks throughout out the monastery, and traditional folk-dance troupes would come there at times, to perform the “goddess” plays (lha-mo).

Intersession break:

1st of the eighth Tibetan month to the 7th of the eighth

Tibetan month; this is the main “water break”

Session Six: The Dharma Session of Medicine Buddha (sMan-bla chos-thog)

Starting assembly: 8th of the eighth Tibetan month

First firewood break: 9th and 10th of the eighth Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: (no geshe debates)

First actual debate session: begins 11th of the eighth Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 22nd and 23rd of the eighth Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 24th of the eighth Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 7th of the ninth Tibetan month

This session takes its name from the fact that an extensive Medicine Buddha rite is held on the 11th of the eighth month.

Intersession break:

8th of the ninth Tibetan month to the 16th of the ninth Tibetan month

Session Seven: The Great Dharma Session of Autumn (sTon-chos chen-mo)

Starting assembly: 17th of the ninth Tibetan month

First firewood break: 18th and 19th of the ninth Tibetan month

Great debate examinations: winter lingse geshe examinations, 20th and 21st of the ninth Tibetan month

First actual debate session: begins 22nd of the ninth Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 2nd and 3rd of the tenth Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 4th of the tenth Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 16th of the tenth Tibetan month

Intersession break:

17th of the tenth Tibetan month to the 16th of the eleventh Tibetan month

Session Eight: The Great Dharma Session of Winter (dGun-chos chen-mo)

Starting assembly: 17th of the eleventh Tibetan month

First firewood break: 18th and 19th of the eleventh Tibetan month

The great examinations: 20th to the 23rd of the eleventh Tibetan month; debate examinations for the winter lingse geshes and hlarampa geshes, the former presenting their “dry recitation”

First actual debate session: begins 24th of the eleventh Tibetan month

Mid-term firewood break: 12th and 13th of the twelfth Tibetan month

Second actual debate session: begins 14th of the twelfth Tibetan month

Auspicious conclusion: 16th of the twelfth Tibetan month

Intersession break

This break features further examination of winter lingse geshes, the Tibetan New Year, and the Great Prayer Festival; it begins on the 17th of the twelfth Tibetan month and ends on the 25th of the first Tibetan month.

Annual Special Events

Passing On of Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (mKhas-grub dgongs-rdzogs)

14th day of the fifth Tibetan month

Kedrup Tenpa Dargye (1493-1568) was an illustrious scholar from Sera Mey who wrote many of the monastery’s textbooks. On special days like this, the monastery will be covered at night in strings of brightly colored electric lights that look like our Christmas-tree lights.

Summer Offering to the Two Dharma Protectors (Chos-skyong rnam-gnyis kyi dbyar-gsol)

15th day of the fifth Tibetan month

This particular day every year is known throughout Tibet as the “Day of Auspiciousness throughout the World” (‘Dzam-gling spyi-bzang). At Sera Mey, the occasion is used as an opportunity to thank the dharma protectors of the monastery for their help, and to request that they continue their sacred deeds. The two protectors here are Chamsing (lCam-sring) and Taok (Tha-’og). The protector Chamsing is shared with other monasteries, while Taok is a unique protector for Sera Mey. Please note that these two protectors have nothing to do with the current dharma protector controversy.

Rikchung (Pre-Geshe Degree) Debates

25th to the 28th of the sixth Tibetan month

First team

Proponent takes the subject “Turning of the Wheel,” opponent takes “Book of Maitreya”: 25th of the sixth Tibetan month

Each of the subjects mentioned here are important topics from the Ornament of Realizations, spoken to the realized being Asanga by Lord Maitreya around 350 AD.

Second team

Proponent takes “Sutra and Commentary,” opponent takes “Final End”: 26th of the sixth Tibetan month

Third team

Proponent takes “Wish for Enlightenment,” opponent takes “Path of Preparation”: 27th of the sixth Tibetan month

Fourth team

Proponent takes “Three Refuges,” opponent takes “Buddha Nature”: 28th of the sixth Tibetan month

Summer Examinations

8th of the seventh Tibetan month

Extensive Medicine Buddha Rite

11th of the eighth Tibetan month

Great Winter Examinations

8th of the eleventh Tibetan month

Assembly of the Great Offering Ceremony for the Prayer of Maitreya

(Byams-smon sgrub-mchod chen-mo yar-tsogs) 25th of the eleventh Tibetan month

Khen Rinpoche notes that, in Tibet, this entire ceremony took nearly a month. The 17th of the eleventh month marks the opening ceremony for the session, and is followed by two days of a firewood break. The 20th and 21st are marked by the “dry recitations” for the winter lingshe geshes, and then the next three days are examinations for the hlarampa candidates. Finally, on the 25th, the actual prayer begins: all of the monks together recite the entire relevant work by the Buddha from memory. At Sera Jey, the recitation for this period is the Prayer of the Deeds of Samanta Bhadra (bZang-spyod smon-lam), also by Lord Buddha. The Prayer of Maitreya continues until the 13th of the twelfth Tibetan month.

Great Torma Offering of the Twenty-Ninth (dGu-gtor chen-mo)

29th of the twelfth Tibetan month

This is one of the year’s biggest prayer ceremonies; the next day is the last day of the year, the new (black) moon (gnam-gang).

Presentation of the Debate Ground Schedule (Chos-grvar tsogs-gtam ‘bulyun)

16th of the third Tibetan month; 26th of the fifth Tibetan month; 16th of the eighth Tibetan month; and 26th of the ninth Tibetan month

On these four dates of the year, the debate master (dge-bskos) stands in the assembly of the debate park to announce the schedule for the coming period. He also outlines the duties that different members of the monastery will be expected to fulfill during this time, and reviews the general rule of behavior for the monastery from the monastery constitution (rtza-khrims, also known as a bca’-yig). This document for Sera Mey was written by His Holiness the Eighth Dalai Lama, Jampel Gyatso (1758- 1804); copies were very rare following the invasion of Tibet. A complete carving was located and supplied to Sera Mey several years ago by Asian Classics Input Project staff at the Oriental Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg, Russia.

Supplement to Reading Ten

Rikpay Drotang

Debating Format, Part Three

Korwa la ta yupay chir

A: Because the cycle of pain does have an end.

Tak madrub

B: Wrong.

Korwa la ta mepar tel

A: Are you telling me the cycle of pain doesn’t have an end?

354

Du

B: Right.

Me de

A: Why not?

Korwa la ngun gyi ta mepay chir

B: Because the cycle of pain has no front end.

Kyappa ma jung

A: That doesn’t mean it can’t have an end!

Korwa la ta yu par tel

B: Are you telling me the cycle of pain does have an end?

Du

A: Right.

Yu de

B: Why so?

Korwa la chiy ta yupay chir

A: Because the cycle of pain has a back end.

Yude

B: Why so?

Dakdzin gyi nyenpo top den yupay chir

A: Because there is a powerful antidote that will smash our habit of seeing things as self-existent.

See also

- Manual of Pramana - Reading One: Why Study the Art of Reasoning?

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Two: An Outline of All Existing Things

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Three: Quality and Characteristic

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Four: Causes and Results

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Six: Negative and Positive

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Seven: Contradiction and Relationship

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Eight: Definitions and the Things They Define

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Nine: The Concept of Exclusion in Perception

- Manual of Pramana - Reading Ten: The Concept of Time

- Manual of Pramana - CLASS NOTES part 1

- Manual of Pramana - CLASS NOTES part 2