Why is Guan Yin not wearing Chanel?: The development of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism and its manifest in material culture by Chan Chow Wah

Why is Guan Yin not wearing Chanel?: The development of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism and its manifest in material culture

By

Mr. Chan Chow Wah

Independent scholar, Singapore

The Buddhist Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara is one of the most popular Chinese religious personalities in China and among the overseas Chinese. Commonly known as Guan Yin (观音) or Guan Yin Pusa (观音菩萨), the bodhisattva is worshipped by Chinese Mahayana Buddhist and has also been incorporated into the Taoist pantheon.

As one of the most popular Chinese deities, Guan Yin also has the greatest diversity in her depiction including a change in gender. While Guan Yin’s worship and history have attracted much academic research, the style and evolution of Guan Yin’s fashion as reflected in material culture relating to her has not received equal attention.

In either male or female form, Guan Yin’s costume has historically reflected the fashion and cultural taste of the social and political elite of each period as the Bodhisattva went through a long process of sinicization. This reflection of contemporary fashion ceased after the Song dynasty. Thereafter, Guan Yin’s fashion cease to reflect the contemporary styles and is seen either in the white robe or in her earlier versions.

If Buddhist art historically reflects contemporary fashion and cultural taste especially that of the social and political elite of each period, then Guan Yin would have been dressed in the leading global fashion brands of today such as Chanel, Gucci or Louis Vuitton. But she has not hence the question, why is Guan Yin not wearing Chanel?

To answer this question, I will briefly discuss the history of Buddhism in China with specific focus on the rise of Guan Yin. Using material culture mainly from the Tang and Song dynasty, I will examine how the contemporary styles are reflected in them. This way we can see how contemporary society influence the production of Buddhist material culture and how this relationship ceased after the Song dynasty.

Guan Yin material culture

Since the arrival of Buddhism in China during the Han dynasty, images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, guardians, apsaras, devas, Buddhist personalities and even the occasion devotee has been the subject of Buddhist material culture.

Production of major Buddhist material culture included sculptures carved onto rock surfaces or painted on cave walls and were often commissioned by political elites. Material culture on smaller scales existed in the form of sculptures made of clay, stones, lacquer, precious metals, rare materials and later ceramics and paintings.

These material cultures were produced for devotional purposes and also as works of art for cultural consumption.

Large quantities of these material cultures were destroyed during periods of Buddhist persecution in China, damaged during wars or as a result of natural wear and tear. The material cultures that have survived, were excavated or still in existence provided valuable information to study the relationship between Buddhist material cultural and the status of Buddhism in each period as well as the larger trend in the development of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism.

Rise of Guan Yin

The Parthian monk, An Shih-Kao’s arrival in 148 marked the introduction of Buddhism in Han China (Yü, 2000). The Buddhist missionaries began translation of Buddhist scriptures to their new audience and at least three centres of Buddhism emerged in Peng Cheng, Luoyang and Tokin (Ch'en, 1972). Buddhism interacted with indigenous Taoism and Confucianism and began the long process of sinisation.

In less than half a century, one of the earliest scriptures mentioning Guan Yin was translated in 185 (Yü, 2000). However, Guan Yin was still a minor figure in China at this point. This situation probably explains why museums today cannot identify with certainty sculptures that they believe to be pre Tang Guan Yin[1]. It was during the Tang dynasty that Guan Yin’s prominence grew as a result of the popularity of Tian Tai, Hua Yan and Pure Land schools (Yü, 2000).

Guan yin’s rise in prominence is reflected materially in the Lung men caves with Amitabha Buddha and Guan Yin sculptures dominating the Long men landscape after 650 (Ch'en, 1972). Since then, Guan Yin became the most worshipped figure in the Buddhist pantheon. (Fong, 1965).

Today, Guan Yin is worshipped in her own right and Chinese forest tradition monasteries (丛林寺院) often have a separate section dedicated to her known as the Guan Yin Hall (观音堂) (Ming, 1986). There are also monasteries dedicated to Guan Yin as well as shrines in homes or business locations of devotees.

Among the Taoists, Guan Yin is also worshipped in her many transformations similar to the Buddhists, forms part of the Taoist pantheon and manifested through spirit mediums, a phenomena unique to the Taoist tradition.

Guan Yin’s popularity also seem to be rising as indicated by the devotee’s offering and prayers during her feast days and more significantly, by her promotion to the position of main deity in some important overseas Chinese temples that were previously dedicated to other Taoist deities. The two most prominent examples are Penang Kuan Yin Temple (槟城观音亭)on Pitt Street in Penang, Malaysia and the Kheng Hock Keng (庆福宫) in Yangon, Myanmar.

Both temples were originally dedicated to Mazu (妈祖), the sea goddess but have subsequently installed Guan Yin as the chief deity.

Tang culture and Guan Yin

In 618, the Tang dynasty successfully united China after almost 400 years of political division. The Tang capital Changan was the largest city in the world with probably a million habitants (Ebrey, 2010). The Tang Empire had extensive trade links and cultural contacts especially with Central Asia. This cultural exchange and fascination with Central Asia influenced the fashion tastes of the social elites.

Benn (Benn, 2004) traces waves of foreign styles that the social elite sought as the latest fashion. The Tu-Yu-hun riding hats of early Tang gave way to curtain bonnet decorated with jade and kingfisher feathers of early 8th century. Women also enjoyed masculine attire and boots inspired by the pastoral people from northeast of China.

By middle of 8th century, Central Asia and possible Persian clothes became popular with Tang man who began wearing leopard skins and women wearing tight sleeves and collars. By the end of 8th century, Uighur fashion were in vogue. In Tang China, plump ladies were admired and the most famous of them was Yang Guifei the favourite consort of Xuan Zong (Michaelson, 1999).

In the Tang social landscape of cultural diversity, Tian Tai, Hua Yan and Pure Land School grew in popularity (Yü, 2000) ushering the rise of Guan Yin and the production of Guan Yin related material culture (Roberts, 2003).

Tang period Guan Yin were depicted in male form and often “round with layered chins, while the body of the images become supple in a natural sway. The trend could have been influenced by contemporary standard of ideal beauty, which emphasized fullness of face and body.” (Yü, 2000). On a more general level, Fong notes that “the contemporary ideal beauty of plump body and placid, full face with small mouth is adopted in the Buddhist images of the Tang dynasty.” (Fong, 1965)

This reflection of contemporary taste on Guan Yin material culture is hypothesised by Yu as an attempt by Guan Yin converts to present Guan Yin in ways that were more congenial to Chinese audiences. Various versions of Guan Yin were produced and eventually some such as the Water Moon Guan Yin became Pan China and while others were forgotten (Yü, 2000).

Song Culture and Guan Yin

After the fall of Tang dynasty, China was divided for about half a century until the Song dynasty united China again in 960. The Song notion of beauty departed from the plump bodies of the Tang to slender body types. The elite Song women comb their hair backwards into a chignon and adorned their hair do with artistically arranged hairpins and combs. For those who can afford it, gold and silver hair accessories produced in the shapes of phoenix and flowers complete the look. During the Song dynasty, two major developments happened to Buddhism in China. Only the Chan and Pure Land remain active but no major Buddhist cleric emerged no new sutras were translated and no new school of Buddhism emerged (Ch'en, 1972).

With regards to Guan Yin, the early Song period saw Guan Yin’s transformation into a female White Robe Guan Yin, the dominant image that continues to this day. Scholars have also proposed that the white robe was inspired by the clothes of common Song people. (Yü, 2000)

Buddhism’s relationship with Taoism and Confucian also converged under the trend of “Three Teachings in one” movement. (Yü, 2000)

These developments during the Song were identified as the start of decline of Buddhism in China (Ch'en, 1972) . However, this period of “decline” can also be argued as the start of institutionalisation of Buddhism in China that has continued to present times. From a polytheistic perspective, the interaction between Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism is not as problematic relative to a monotheistic view. Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism do not reject the existence or validity of other belief systems. In fact, Mote points out that religious beliefs cannot be understood by trying to separate them into distinct beliefs and practises…” (Mote, 2003).

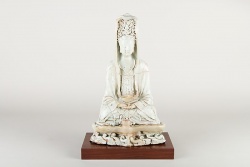

It is interesting to see corresponding perceptions of “decline” among scholar with regards to material culture. Two early Sung Guan Yin sculptures were identified as the best of the dynasty and even as the “last great examples of Buddhist sculpture in China” (Fong, 1965).

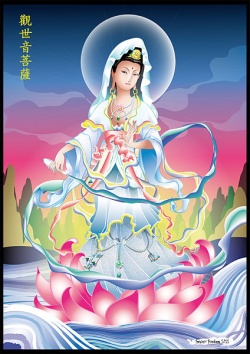

As Buddhism “settled down” in China and harmonised with Taoism and Confucianism, Guan Yin’s material culture also “settled down”. After the transformation of the male Guan Yin into the female white robe Guan Yin, her fashion reminds unchanged to this day although she has various manifest in white robe such as the Guan Yin of the Southern Seas (南海观音), Guan Yin with willow leaf (杨柳观音), Guan Yin as giver of sons (送子观音) or Guan Yin of the purple bamboo forest (紫竹观音).

There are also female white robe Guan Yin interpretations of earlier male forms such as the Water Moon Guan Yin (水月观音). Other forms of Guan Yin such as the thousand arm Guan Yin (千手观音) continues to be shown in male form.

Conclusion

I have presented the rise of Guan Yin from the Tang to the Song dynasties and show how the Guan Yin were conceptualised and inspired by contemporary fashions and tastes.

The transformation of Guan Yin cease after the Song dynasty, a point where scholars identified as the decline of Buddhist and when Buddhism integrated with Taoism and Confucianism.

I propose that Guan Yin is not shown wearing Chanel because of the institutionalisation of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism during the Song dynasty. As a result of this institutionalisation, Guan Yin’s fashion cease to evolve and cease to reflect the contemporary fashion. Buddhist material culture on one hand reflects devotee’s notion of the Bodhisattva and reflects the development of Buddhism in China on the other. Seen in this way, the material cultural relating to Guan Yin changed from its role as a contemporary reflection and imagination of Guan Yin to become a standard icon her.

Therefore, Guan Yin is not wearing Chanel not because she cannot wear it. It is just that she has not wear Chanel yet.

References

- Benn, C. (2004). China's Golden Age. Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press.

- Ch'en, K. (1972). Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. Princeton University Press; New Ed edition.

- Ebrey, P. B. (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Fong, C. (1965). Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 23, no. 9, part 1.

- Gernet, J. (1762). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276. Stanford University Press.

- Gernet, J. (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press.

- Michaelson, C. (1999). Gilded Dragons: Buried Treasures from China's Golden Ages. The British Museum Press.

- Ming, K. (1986). An Introduction to Chinese Buddhism. Kuan Yin Contemplative Order.

- Mote, F. (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press.

- Teoh , E. S. (2004). Guan Yin A hundred and one questions. Singapore: Gallery99.

- Yü, C.-f. (2000). Kuan-yin : the Chinese transformation of Avalokitesìvara. Columbia University Press.

Footnotes

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art has several sculptures that they believe but cannot identify with certain is Guan Yin;

Northern Wei: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/42711

Northern Qi http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/42718

Source

Buddhism And Australia Conference 2015 http://buddhismandaustralia.com/