Image Consecrations

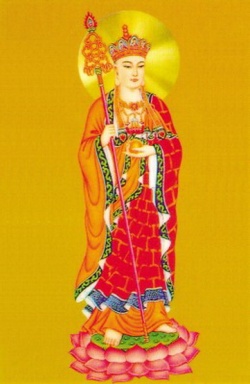

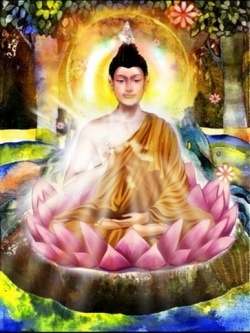

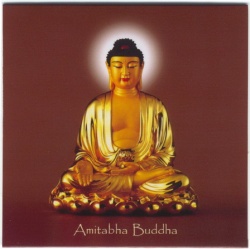

The preceding excerpt dealing with temples and monastic complexes clearly depicts the presence and importance of images of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other deities and divinized figures. The spiritual or supernatural power and efficacy represented, embodied, or actualized in such images allows them to mediate memories, blessings, and protection to the Buddhist community and to Buddhist devotees who offer their veneration.

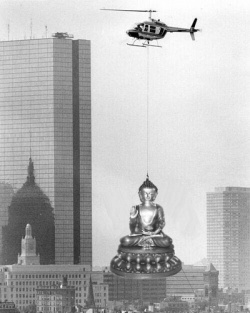

Though images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas generally have very distinctive aesthetic qualities, their aesthetic form does not fully account for the sacred power that they are believed to possess. In many cases, especially when images are considered to be particularly efficacious, they have been imbued with sacrality through a sophisticated process of ritual consecration.

Buddhist processes of consecrating images vary a great deal from one region to another and depend to a considerable degree on the sacred figure whose image is being consecrated. However, Buddhist traditions generally retain the lengthiest and most sophisticated consecrations for Buddha and/or bodhisattva images. Such consecrations often involve, among other elements, preaching, recitation of key Buddhist texts, and, as with virtually all Buddhist rituals officiated by members of the monastic community, the presentation of lay gifts to the sangha. The following excerpt presents an account of the particular ritual process employed in 36 TEMPLES, SACRED OBJECTS, AND RITUALS

northern Thailand in the consecration of images of the Gautama Buddha. (In the following essay, since he is dealing with a Theravada tradition, the author uses the Pali forms of Buddhist terms. For example, he uses Gotama rather than Gautama, dhamma rather than dharma, nibbana rather than nirvana, and so forth.)

Donald K. Swearer

Buddha image consecration ceremonies in northern Thailand can be held at any time of the year. Generally speaking, however, they occur after the end of the monastic rains retreat (vassa) and prior to the Visakha Puja, the celebration of the Buddhafs birth, enlightenment, and death. Consequently, even though there is no stipulated season for the consecration of a Buddha image, the ceremonies tend to occur more frequently between November and May. Although Buddha image consecration ceremonies in northern Thailand may be held at almost any time of the year, to the best of my knowledge they always take place within the precincts of a monastery (Thai: wat).

I have never heard of a Buddha image consecration ritualfs being held in a home, which is the common practice in Burma for a home shrine image. Northern Thai consecration rituals may vary considerably in specific details: the length, the specific texts chanted and preached, the number of images or other sacred objects (e.g., amulets) being consecrated, the number of monks involved, the number and status of lay sponsors, and the building in the monastery compound where the ceremony is conducted. Although image consecrations may occur at virtually any time of the year and can extend over more than one day, the northernThai consecration ritual takes place during the night with the climax occurring just before sunrise.

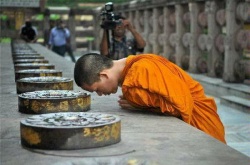

The timing of the ceremony homologizes the event with the episode of the Buddhafs enlightenment, which progressed through the watches of the night and culminated at sunrise. Furthermore, although the rituals may vary greatly in specific details, they contain four basic components: chanting, preaching, meditation, and presentation of gifts to the sangha. Consecration rituals usually take place within a specifically constructed sacred enclosure inside the vihara, the image hall where most public meetings are held. A royal fence (rajavati) demarcates the perimeter. A string strung from the principal vihara image (previously consecrated) intersects over the rajavati to form a virtual ceiling of 108 small squares. This is the same sacred thread (Thai: sai sincana, or waterpouring thread) held by monks as they chant during all types of religious services. It plays a crucial role in transferring or conducting sacred power from a particular source, especially a Buddha image, to animate or inanimate objects and is essential in making holy water, that is, water sacralized through the chanting of mantras (formulaic sacred words or sounds).

Numerous distinctive objects are situated in and around the rajavati, including four clay jars filled with water, four nine-tiered umbrellas, stalks of bamboo and sugarcane, bunches of coconuts, pedestal tables, piled high with small cone-shaped banana leaf containers of fragrant flowers and incense, betel nuts and betel leaves, and husked and unhusked rice. Also to be found are a table with a monkfs bowl and other monastic requisites and a stand with emblems of the eight royal requisites (sword, spear, umbrella, banner, etc.). The images to be consecrated are placed in the center of the rajavati on small beds of grass, eyes covered with beeswax and heads hidden by white cloth.

The extent and variety of objects suggest different but interrelated levels of meaning. Several symbolize the story of Prince Siddhatthafs renunciation of his royal status in quest of a higher enlightenment. (According to the classical Buddha biography, Siddhattha was the given name of the person who came to be known as the Gotama Buddha.) The emblematic requisites of both kingship and monkhood denote Siddhatthafs mythic journey from his royal household to the attainment of Buddhahood. The grass on which the images rest represents the gifts of eight tufts of coarse kusha grass given to the Buddha prior to his enlightenment by the Brahman Sotthiya; the grass magically became a crystal throne.

The central event of the Gotama Buddha story is Prince Siddhatthafs enlightenment, or attainment of Buddhahood. The crucial referent for the Buddha image consecration ritual is the description of the course of the attainment of enlightenment through the watches of the night. The beeswax closing the eyes and the white cloth covering the head suggest the Buddha prior to his enlightenment. Mouth, nose, and ears may also be sealed with beeswax, perhaps to guarantee that none of the power being charged into the image will escape. Such a sealing off of the image would also appear to safeguard the sacralization process as well as to protect those present at the ceremony from the intensity of the energy being generated within the image. Three small mirrors mounted on a cruciform stand facing the images symbolize the Buddhafs attainment of the three knowledges (i.e., enlightenment): knowledge of the recollection of his past lives; knowledge of the coming into being and passing away of all beings; and knowledge of the destruction of mental intoxication. Reversing the mirrors at the conclusion of the ritual represents the completion of Prince Siddhatthafs spiritual journey and the attainment of omniscience.

The structure of the rajavati, furthermore, suggests a second level of meaning imbedded in the ritual. The ceiling of 108 squares is referred to as a magical cosmos. It resembles a geometric mandala (sacred circle) touching the earth through the conduits of sacred cord hanging from its perimeter. The objects at the entrances represent objects basic to traditional village existence.sugarcane, bamboo, coconuts, bananas. elements used in ceremonies to ward off evil and engender good. The clay jars filled with water, various candles, and a peacock fan represent the four constitutive elements, or dhatu.earth, water, fire, air.

Therajavati also fuses the polarity between the religious and royal realms, so central in the sacred biography of the Buddha. The royal fence establishes the horizontal perimeter of the sacred enclosure within which the images are consecrated. Yet, reminiscent of Siddhatthafs journey beyond the walls of the royal city, when the gtrainingh of the images is complete, the rajavati no longer serves a useful function and is dismantled. The eveningfs events begin around 7:30 p.m. with monks and assembled laity paying respects to the Buddha, taking the precepts, and asking forgiveness for transgressions.

Lighting a victory candle constructed of a wick of 108 strands (the combined cosmic powers of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha) and made to the height of the chief sponsor, initiates the consecration ritual proper. The officiating monk chants: By the power of the Omniscient Buddha, the supermundane Dhamma, and the highest virtue-attaining Sangha may all suffering, calamities, and dangers vanish. May all beings live without injury.h The chief sponsor then lights a large candle invoking the Buddha Vipassin, the first of the last six Buddhas preceding Gotama, and two candles on either side symbolizing the lokiya (mundane) and lokuttara (transmundane) dimensions of the Buddha-dhamma.

The eveningfs main activities alternate among chanting, preaching, and meditation. Chanting includes paritta (protection) suttas from the standard Theravada repertoire as well as texts unique to the northern Thai ritual context. In most image consecration rituals throughout Thailand, the PaliBuddha Abhiseka will be chanted. At that time nine or more monks sit in meditation around the rajavati with the sai sincana cord extending from alms bowls placed in front of them to the Buddha images and amulets being consecrated. The monks invited to meditate for this occasion are often renowned for their attainment of extraordinary powers associated with trance states (jhana).

By recalling or recollecting these attainments during their meditation, the monks transfer them to the image. At the same time many of the lay congregants sit in meditation, some having encircled their heads with sai sincana cords hanging down from the linked squares forming a ceiling over the images. While the assembly meditates, bronze Buddha images reflect the flickering light of burning candles, and the hall reverberates with the cadence of monks chanting the story of the Buddhafs enlightenment. In such a numinous, liminal environment, the transformation of material object into living reality seems palpably true. By this sustained, focused act of attention, the image as ritual object becomes sacred. Furthermore, this act of commemoration of recollection (buddhanussati) calls forth a profound sense of communal identity linking the assembled congregants and the Buddha.

In northern Thailand monks frequently preach the Buddha Abhiseka in northern Thai as well as chant the text in Pali. Other northern Thai sermons will invariably include the Buddhafs First Enlightenment (Pathama Sambodhi) as well as one or two other traditional favorites of this occasion, such as Siddhatthafs Renunciation. As we would expect, all of the sermons recount the life of the Buddha, especially the events of his renunciation and training, his conquest of Mara, and the night of his enlightenment.

In addition to recounting the Buddha story, the texts also impart the seminal teachings of the Buddhafs dhamma, for example the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Noble Path, Dependent Coarising, and so on. The most dramatic teaching event occurs at the end of the ceremony. At sunrise, when the images have been duly consecrated, the monks chant the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (Discourse on the Turning of the Wheel of Law) in reenactment of the Buddhafs first discourse to the five ascetics.

Prior to the conclusion of the ceremony several other important events take place: the cloth and beeswax coverings are removed from the heads of the images, the images are fanned with a long-handled peacock fan, they are presented with forty-nine bowls of milk and honeysweetened rice, and, finally, images and congregants are blessed with holy water.

The removal of the headcoverings symbolizes the completion of the training of the image or, as it were, the Buddhafa attainment of enlightenment. Coincidentally, of course, the assembled congregants have also

been gtrained.h The fanning of the images and the presentation of sweetened rice reenact two events in the legendary life of the Buddha: the god Sakkafs act of respectful veneration toward the Buddha after his enlightenment and the offering of sweetened rice presented to the Buddha under the Bodhi tree by the young woman Sujata. Fanning the image also gcoolsh the heat generated by the transformation of a material object into a living reality.

The sweetened rice is cooked in the early morning hours over a wood fire stirred by young, pre-pubescent girls and then divided into forty-nine bowls symbolizing the seven days the Buddha spent at each of seven sites after his enlightenment. Much of the Buddhabhiseka ritual has mimetic or performative significance. As the very presence of the absent Buddha, the image must be coded with the right story much as an alias is coded with the life story of the person the alias represents, or the actor becomes the role she or he plays, or, from a somewhat different perspective, as we are our particular stories. That is, in being the Buddha, the image is the Buddhafs story.

Since a crucial component of the Buddhafs story is the Buddhafs teaching (dhamma), the image and the congregants are instructed in the dhamma. Furthermore, the chants, sermons, and monk meditators infuse into the images the powers of higher meditative states of consciousness. What is said, in particular what is chanted, and what is done, both in terms of meditation and various ritual movements, are intended to accomplish something, to make something happen, to be efficacious. The image becomes a living representative of the person, career, and power of the Buddha as well as the person, story, and power of charismatic monks.

It will be instructive to look briefly at the two principal texts preached during the consecration ritual. One, the Pathama Sambodhi, rehearses the Buddhafs attainment of thirty perfections from his birth as Prince Vessantra, through his incarnation in Tusita Heaven, his descent into the womb of Mahamaya, his appearance as Prince Siddhattha, his passage through the four sights (old age, suffering, death, mendicancy), his renunciation, his temptation by Mara, attainment of enlightenment, the forty-nine days after his enlightenment, and the preaching of the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta.

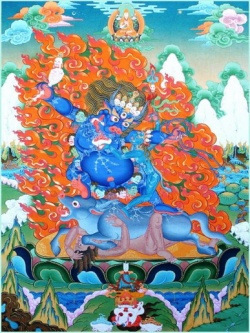

Virtually a quarter of the text focuses on the Buddhafs attack by and defeat of Mara: Marafs forces numbering several hundred thousand were fearsome. With Mara in the lead they came in a procession eighty-five miles in length and breadth and sixty-three miles in height. The divine beings.Indra, Brahma, Yama, the Nagas, and the Garudas.were apprehensive but waited for the Great Being to defend himself and attack the forces of Mara.

1. This translation of the Buddha Abhiseka is based on a version currently preached during the Buddha image consecration at monasteries throughout the Chiang Mai val- Then by their magical powers Marafs army assumed awesome forms that aroused great fear. They carried spears and swords, bows and arrows, and raised a deafening cry. They surrounded the Great Being and then launched their attack, but no harm came to the Blessed One due to his great merit. Then Mara mounted Girinandamekkha, an enormous elephant 1,500 miles tall. Mara himself, standing on the elephantfs neck, was four miles tall. By his magic power he generated a thousand hands, each holding a weapon, and charged the Great Being intent on killing him.

The spears and arrows Marafs army hurled at the Buddha were transformed into flowers and fell as an offering at the feet of the Blessed One. Marafs forces then looked up and saw the Buddha sitting like a lion-king on a lotus in the midst of a wheel, unafraid of the army arrayed before him. The Blessed One reflected, gI embarked on the mendicant path and became a Buddha. I attained the thirty perfections through perseverance. In a previous life I was Prince Vessantara. The generous sacrifice of my wife and children caused the divine beings Indra and Brahma to bless my great gift (dana) with celestial waters. From that time such a blessing is witness to my enlightenment. I gained this diamond throne through the store of my great merit.h

The textfs conclusion transfers the Buddhafs conquest of evil and subsequent attainments to the assembled congregants.

All people who listen to the sermon called the Pathma Sambodhi about the Buddhafsway to and attainment of his final supreme enlightenment and who follow its teachings will attain three kinds of happiness of which the deathless state of Nibbana is the highest. Whether you copy the text on your own or hire someone to do it, give it as a puja offering or just listen to it, you will receive a blessing (anisamsa) and will be reborn in heaven or as a human being greatly beloved by both divine and human beings.

Anisamsa texts constitute an important genre of northern Thai Buddhist literature since the majority of Buddhist rituals are classified as meritoriously efficacious (Pali: punna; Thai:tham pun). Although meritmaking rituals can be justifiably interpreted.as this text suggests.in gmagical,h consequentialist terms, when contextualized as the conclusion to the Pathma Sambodhi, a principal text of the Buddhabhiseka ritual, the anisamsa fits into the gactualizingh intent of the ritual. That is, within the ritual context the blessing follows from the actualization of the Buddha in the experience of the congregants. The Buddha Abhiseka text, which is chanted and/or preached, only briefly summarizes the Buddhafs birth and enlightenment quest.1 The

ley. The text is a redaction edited by Bunkhit Wacharasat, a major publisher of sermons presented to the sangha on various auspicious, merit-making occasions. 2. The eight worldly factors are gain and loss, fame and obscurity, blame and praise, happiness and pain.

bulk of the text focuses on the Buddhafs various supernatural or jhanic attainments, for example: psychic powers; realization of the states of stream-enterer to arahatta-phalanana (these are four states that involve ascending degrees of realization of supramundane reality); attainment of the three knowledges; and transcendence of rebirth. The Blessed One (Tathagata) reached the supermundane state through perseverance and effort. As one in whom the passions are extinct, theTathagata burned up all demerit, and through his wisdom realized the dhamma of cause and not-cause. During the first watch of the night all of theTathagatafs doubts disappeared.

At that time the Buddha was able to recall his previous lives. His heart was pure. Devoid of defilements, he overcame the eight worldly factors.2 In the middle watch he was able to see the death and birth of all beings through the divine eye superior to all human and divine beings. In the last few pages these attainments are infused into the image: The Buddha, filled with boundless compassion, practiced the thirty perfections for many eons, finally reaching enlightenment. I pay homage to that Buddha. May all his qualities be invested in this image. May the Buddhafs boundless omniscience be invested in this image until the religion ceases to exist. . . .

May the Buddhafs boundless virtue acquired during his activities immediately after his enlightenment be stored in this image forever. May the knowledge contained in the seven books of the Abhidhamma perceived by the Buddha in the seven weeks after his enlightenment be consecrated in this image for the rest of the lifetime of the religion. May the power acquired by the Buddha during the seven days under the Ajapala tree, the seven days at the Mucalinda pond, etc., be invested in this Buddha image for 5,000 rainretreats. The Buddha then returned to Ajapalanigrodha where he preached the 84,000 verses of the dhamma. May they also be stored in this Buddha image. May the Mahabrahma (great god) who requested that the Buddha preach come into this image.

The Buddha image consecration ritual concludes at sunrise. The image has been instructed in the life story of the Buddha and empowered with his supernormal attainments. The presence of the Buddha principle represented by previous Buddhas has been invoked in symbolic action as well as chant. Assembled monks and laity gfeedh the image with fortynine small bowls of milk and honey-sweetened rice. As dawn breaks, the monks chant the verses of the Buddhafs victory over the realm of samsaric grasping, his enlightened penetration of the truth of dependent coarising, and the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. Monks remove the headcoverings from the images and respectfully fan them with a peacock feather fan. Finally, the laity feed the monks as they earlier gfedh the Buddha. The sangha sprinkle consecrated water (abhiseka) on images and people and chant a final blessing: gJust as overflowing rivers make the ocean full, so dana given from this world reaches the dead. May all of your wishes be successful. May all your wishes be as complete as the full moon and the bright, shining diamond.

The Buddha image consecration ceremony establishes a common thread of meaning inherent in most Buddhist rituals, and in doing so it connects the founder with the past and present, the dead and the living. Three terms applied to the northern Thai ceremony illustrate this generalized significance: geye opening,h gtraining the image,h and gconsecrationh (abhiseka). To open the eye of a Buddha image is to enliven it, to bring it to life, to make it present, to instill it with power. To train the image is to instruct it in the life history and teachings of the person the image represents. Within the context of Buddhist ritual and ceremonial practice, to abhiseka means to consecrate by means of pouring water or lustrating. At its deepest level, not only to make sacred in the sense of purify but to re-create and make new as represented by the life-giving force of water. To abhiseka, then, is to focus and disseminate power, the power of the sacred, the holy, indeed, the power of life.

An abhisek-ed image or an amulet, be it of the Buddha, a king, or a holy monk, is a locus of such power. But abhiseka also permeates all aspects of life, much as water itself does: a teenager pouring water on the heads or hands of relatives at Thai New Year, a monk using a bamboo whisk to sprinkle water in blessing on an assembled congregation, a lay practitioner anointing a cetiya enshrining sacred relics at a monasteryfs annual celebration. Beyond the images or the rituals themselves, abhiseka expresses a weltanschauung: on one level, a belief in the magical power or potent efficacy of particular material objects such as Buddha images and amulets, but on another, and one too often overlooked, a sense of reality that unifies and makes meaningful an otherwise arbitrary and chaotic world.

The essay in this chapter was adapted from Juliane Schober, gBuddhist Just Rule and Burmese National Culture: State Patronage of the Chinese Tooth Relic in Myanma,h History of Religions 36 (1997): 218 .43. Courtesy of the University of Chicago Press.

State Rituals and

Ceremonies (Myanma)

From a very early stage in its history, Buddhism has been involved in a variety of interactions with the political orders with which it has coexisted. These interactions have ranged from highly positive and relatively symbiotic relationships to situations in which the Buddhist tradition and the political order in question have acted quite decisively to subvert each other.

One relatively positive interaction between sangha and state occurred within two centuries after the death of the Gautama Buddha (in the middle of the third century b.c.e.). At that time, a great Indian monarch named Asoka became a strong supporter of Buddhism and used his authority to influence the composition and orientation of the sangha. Asoka encouraged the spread of the religion in innovative ways that simultaneously attempted to promote social harmony on a large scale and to legitimate his rule. In almost all the Asian areas where Buddhism has spread, it has.at various times.been linked with kings who have taken on a Buddhist identity and have sought to control and support Buddhist society (including both monastic and lay components) within their realm.

In carrying forward their efforts to control and support the sangha and laity, Buddhist kings have sought to demonstrate their piety through a variety of means. One of the most common and historically signifi

1. In this essay, I will use the names gBurmah and gMyanmah interchangeably. In 1997, a shake-up occurred and the name of the ruling group was changed to the State Peace and Development Council. However, this has generally been seen as a change in name rather than substance.

cant strategies has been the cultivation of a special relationship with, and veneration of, particularly potent embodiments of the Buddhafs sacred power. In many cases this particular relationship has been centrally concerned with public rituals and ceremonies that crystallize around a bodily relic supposedly retrieved from the ashes after the Buddhafs cremation. Perhaps the most famous example of such bodily relic. oriented ritual and ceremonial activity is that associated with the tooth relic presently housed in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, the highland city that once served as the capital of Sri Lanka. During much of the medieval period, this relic served as the palladium of the Sinhalese kings who ruled the island.

In the excerpt that follows, Juliane Schober describes a recent series of events in which another Buddhist tooth-relic tradition was employed by the present military government of Myanmar to legitimate and solidify its rule.

In early 1994, the military-dominated State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) which then governed Myanma1 enjoined millions of people in Burma to participate in a series of elaborate rituals so citizens and foreigners could pay homage to the Chinese Tooth Relic during its 45-day-long procession throughout the nation. This ritual veneration of the Buddhafs relic exemplifies a modern transformation of an established mode in traditional, cosmological Buddhism. Participation in its economy of merit transforms a ritual community into a national community in which the state regulates access to merit, prestige, and power through complex hegemonic structures. This essay explores the ritual theater of the state to show how this Buddhist ritual process operates to obligate national elites in various domains, and ethnic groups in the periphery, to the hegemonic structures of the center. The analysis presented here draws on contemporary media texts and on anthropological fieldwork in various contexts of venerating the Sacred Tooth.

2. In the Theravada tradition the two bodies of the Buddha that persist after his death are his dhammakaya (body of teachings) for which the monks assume primary responsibility and the rupakaya for which the laity is expected to show special care. The rituals described here occurred in the context of a crisis of authority that has endured in Myanma since 1988 when the national constitution was abolished and a military regime assumed power. This crisis of authority intensified after 1990 when the SLORC refused to honor popular elections favoring a democratic multi-party system. Despite economic reforms that largely benefited the privileged, the experiences of the past decade have proven painful to many and have further exacerbated divisions within the national community. Particularly harsh have been the controls that SLORC has instituted over the Buddhist sangha and the severe punishments that have been imposed on monks who have criticized the regime.

As the state has continued to operate without a national constitution, the absence of secular mechanisms for legitimating political power structures has led to a renewed emphasis on traditional religious means of legitimation, albeit within modern contexts. In the absence of a secular, constitutional legitimation of state powers, the SLORC regime has relied increasingly on its patronage of Buddhist relics and symbols. It has lavishly sponsored the veneration of the rupakaya of the Buddha as a populist strategy for legitimation, and as a venue for implementing its vision of a national ideology and community. (Therupakaya is the gform bodyh or material body of the Buddha that is identified with his relics, with stupas or pagodas which are funerary monuments that usually contain a relic, with images, and with other similar kinds of sacred objects.)2

The elaborate and expensive ritual theater that the government has undertaken has been aimed at multiple audiences and has deftly deployed Buddhist symbols that have great resonance in Burmese history, culture, and politics. But despite the use of traditional cosmological and mythological motifs, the needs that the state-sponsored veneration of the Buddhafs relic have been designed to address have emerged out of the pragmatics of modern politics. This state-sponsored veneration has been generated in order to legitimate political hegemonies, to mobilize large and diverse numbers of people, and to promote the political and cultural integration of an imagined national community. The ritual gprogressh (dethasari) of the Sacred Tooth in Burma can therefore be seen as a vehicle for negotiating hegemonic visions of a modern nation, the moral authority of political elites, national community, history, and culture.

Setting the Stage

The ritual journey (dethasari) of the Chinese Tooth Relic from Beijing, China, to Yangon,Myanma, and upcountry between April 20 and June 5, 1994, constituted a culmination within a broader cult of national veneration of stupas, images, relics, and similar sacred objects, and of an extended series of state-sponsored rituals featuring political functionaries and their subordinates in public settings throughout the nation. A series of state-sponsored rituals that dramatized SLORCfs religious authority preceded the arrival of the Sacred Tooth in Burma. The weeks leading up to the culminating ritual journey were marked by Myanmafs 1994 New Year celebrations in which SLORC functionaries assumed public roles in various ritual contexts.TheNewLight ofMyanma (NLM), a major government-run daily paper, described SLORC elites as rightful patrons who deserved popular respect.

It also depicted state officials as jovial recipients of water absolutions (abhiseka) from state employees in public settings orchestrated for this purpose by ministries and state offices in the capital and in urban centers throughout the nation. Large public gatherings and merriment celebrated the auspiciousness of the BurmeseNew Year with traditional songs and dances. Following this initial ritual affirmation of political hegemony, political elites performed water absolutions at rupakaya sites, including pagodas, Buddha images, and Bodhi Trees throughout the nation. These rituals were symbolic assertions of SLORCfs role as rightful patron of rupakaya and restorer of royal sources of merit in Myanmafs history and culture. The Sacred Toothfs procession similarly created fields of merit that mapped a universal Buddhist cosmology onto the territory of a modern nation.

It placed SLORC in a lineage of past kings and obligated to it ritual clients comprised of military, technocratic, business, and ethnic elites. In preparing for the Toothfs arrival, SLORC planned a procession (dethasari) of cosmic proportions. The processionfs splendor combined traditional Buddhist symbols of devas residing in the heavenly realms, and regalia of a just ruler (dhammaraja) with modern technology like Boeing 737 jet aircraft, luxury cars and buses. Complex preparations heralded its journey.

Ministers and other highly placed officials attended multiple coordination meetings in order to develop a protocol for the gconveyance of the Sacred Toothh that was modeled after Burmese traditional prescriptions for the royal procession. Their discussions considered such things as arrangements for the relicfs itinerary; the artistsf work to construct an encasement and throne upon which the relic would rest; reports on the physical condition of the elephant that was to carry the sacred object in procession from the airport to its temporary residence at Kaba Aye, the famous Buddhist center in Yangon; the closure of traffic routes due to large-scale dress rehearsals prior to its arrival; and arrangements for security, crowd management, and health emergencies.

Extensive reports of preparations as well as of the actual ritual events appeared in government-run print, audio, and video media. Journalists, film makers, and other government mass media representatives participated in high-level planning sessions to ensure a public relations success. After the relics arrival, daily radio broadcasts featured songs venerating the Tooth Relic. Rituals were televised routinely and a commemorative video was produced for sale to the public.

The statefs patronage of religion and especially of the Buddhafs rupakaya was carefully featured alongside reports of modernization projects and in editorials explicating the statefs vision of modernity and Buddhism. The placement within the paper of the reports related to the Tooth Relic similarly pointed to the significance attributed to these rituals. A logo of the Sacred Toothfs encasement accompanied all coverage over the two-month period. It was often placed near or beneath government slogans praising the militaryfs sacrifice and accomplishments in furthering national unity, peace, and prosperity. Clearly, the message was that the military.like the relic.was worthy of support and reverence by citizens.

The construction of SLORCfs ritual community as national community, and of a national history associated with the statefs vision of Buddhism, was clearly evident in editorials about the Tooth Relicfs procession and its significance. The following comment in an editorial put out by the NLM is representative:

With the State Law and Order Restoration Council working overtime for the promotion, propagation, and perpetuation of the Sasana (the Buddhist religion), it is a great reward for the people of this land that the Tooth Relic has been brought on a dethasari journey for the benefit of all who would like to take the opportunity to pay homage.

The Progress of the Sacred Tooth

Traveling from Beijing aboard a special Air China flight that briefly stopped in Kunming, Yunnan (a province in Southern China that borders Myanma), the Buddhafs Tooth Relic was accompanied by a delegation of eight Mahayana monks, three Tibetan lamas, four Yunnanese

3. In the mid-1950s, U Nu, the post-independence prime minister of Burma, sponsored an elaborate international synod to celebrate the 2,500-year anniversary of the founding of Buddhism.

Theravada monks, and eleven lay persons. This last group included Mr. Luo San Chinai, the Deputy Director of the Chinese Bureau of Religious Affairs, Lt. Gen. Myo Nyunt, a prominent SLORC leader who served as Minister of Religious Affairs and Chairman of the Buddha Tooth Relic Conveyance Work Committee, as well as officials from the religious and foreign affairs ministries. When the relic arrived at Yangonfs International Airport, it was officially welcomed by Secretary- 1 Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt (also a prominent leader in SLORC), Myanmafs chief justice, the attorney general, other ministers, seniormembers of the military, members of the State Maha Nayaka Council (the governmentsponsored council that regulates affairs of the sangha), prominent nuns, leaders of Buddhist lay associations, the Chinese ambassador toMyanma, and representatives of the Chinese Lay Buddhist Association.

A cast of more than 5,000 members of the military, civil servants, actors in costumes of celestial devas, and traditional royal service men staged a grand and dramatic reception. Thousands of on-lookers lined the streets of the capital to watch as the procession passed by with its elephant-drawn carriage and festive emissaries. Its motorcade included the limousines of political and religious dignitaries. It also included dozens of buses with schoolchildren; university students; pagoda trustees; representatives from music, film, and literary guilds; members of the government-sponsored national grassroots organization, Union Solidarity Development Association (USDA); and leaders of Hindu and Chinese religious associations, the Red Cross, and the Fire Brigade. It proceeded past lavishly decorated portals constructed for the occasion along a road that led for several miles to the Maha Pasana Cave at the Kaba Aye in Yangon. At the Kaba Aye, the relic was enshrined and placed on public display around the clock.

Inside this artificial cave, which had also served as the site for U Nufs Sixth Buddhist Synod,3 the relic was displayed in a special encasement placed on a lotus throne and flanked by two replicas and a gilded Emerald Buddha statue whose history is said to be linked to the Chinese Sacred Tooth during the first Burmese empire. SLORC chairman Lt. Gen. Than Shwe and other government ministers were the first to pay homage to the Sacred Tooth and donate money. Later that day, Secretary- 1 Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt and senior monks of the Burmese Maha Nayaka Council publicly venerated the relic, paid respects to the Chinese monastic delegation and met with members of lay associations in charge of continuous chanting before the Sacred Tooth.

The secretary also inspected donation procedures and the jewelry that had been donated. The next morning, the Sacred Tooth again received homage and offerings from Myanmafs head of state, Lt. Gen. Than Shwe, his family, and senior politicians. Food was offered to the Chinese monks and the Sacred Tooth was then made available for public homage. Early each morning, cabinet ministers (in descending rank order), their families, and subordinates made offerings to the Sacred Tooth. For a six-week period, daily television, print, and photo coverage of these rituals featured government officials, public veneration, and tallies of donations that had been made.

Following two weeks of public homage in Yangon, an elaborate float and motorcade commenced a journey that conveyed the Tooth Relic north along a much traveled and historically significant route. The relicfs ritual journey proceeded on SLORCfs newly completed highway from Yangon to Mandalay, the last royal capital and economic center of upper Burma that links several ethnic regions to the nationfs heartland. On its path, the procession stopped at sites of historic and contemporary significance. After five days, it arrived in Mandalay where its public display allowed both sangha and laity to gain merit. After nearly two weeks of public veneration there, the relic was carried south again to Thazi, a market town along the rail track, from where it was flown back to Yangon and again enshrined at the Maha Pasana Cave.

During the final two weeks of display, ritual veneration by the SLORC elite, organized collectives, and the public reached enormous proportions. This final period coincided with the Burmese celebration of the Buddhafs birth, enlightenment, and parinibbana (passing away) on the full moon day of Kazon (May 24, 1994). On June 5, SLORC chairman Lt. Gen. Than Shwe, his family, and high-ranking ministers paid homage, made offerings, and gave donations. Traffic in Yangon was once more rerouted to accommodate a procession in which the Sacred Tooth, carried in its elephant carriage, was returned to Yangon International Airport. At the airport, amidst still more grand ritual theater, the relic was placed on board the plane that flew it back to the Chinese capital of Beijing. Consecrations and Pilgrimages

The relicfs ritual journey set into motion a number of secondary cycles of ritual merit that enhanced and extended its religious and political impact. These ritual cycles fall into two categories. The first includes repeated consecrations of the Tooth and ancillary sacred objects. The second involves pilgrimages to sites of the relicfs temporary residence by various client groups fulfilling their obligations towards the center. The consecrations extended the ritual presence of the Buddhafs relics through the use of long-established patterns in Theravada and Burmese traditions.

The lineage of the Buddhafs relics, represented by the Sacred Tooth, was.in classical Theravada fashion.ritually extended through two replicas fashioned for the purpose of this journey and conveyed along with the goriginal.h The consecrations also included a third sacred object, a Burmese gilded Emerald Buddha image that myth associates with King Anawratha, the famous monarch who established the first Burmese Empire in the eleventh century c.e. According to the legend, the king received the gilded emerald image as a consolation from the gChineseh guardians of the Sacred Tooth Relic who refused to relinquish the relic itself.

In the course of its ritual journey in 1994, the Tooth Relic was consecrated five times. The consecrations, which were performed in a highly theatrical fashion, had as their officiants Chinese and Burmese members of the sangha and were sponsored by the political representatives of SLORC. The first consecration occurred prior to the departure of the Tooth Relic from Beijing and involved Mahayana monks, Tibetan lamas, and 150 Yunnanese monks. Subsequent Tooth Relic consecrations were performed in the presence of the two replicas and Anawrathafs gilded Emerald Buddha statue shortly after its arrival in Yangon on April 30, 1994, and again immediately prior to its departure for its upcountry tour on May 5. Two additional consecrations were performed in the course of the relicfs upcountry journey in Pyinmana on May 8 and then again in Mandalay on May 10.

The three ancillary sacred objects were displayed alongside the Tooth Relic at Kaba Ayefs Maha Pasana Cave where they also received public veneration and were consecrated. The multiple consecrations of the relic itself and of its three associated sacred objects served to augment the number of sites where the Buddhafs remains, or their substitutes, would reside in Myanma. With donations collected during the relicfs visit to Burma, SLORC has since completed the construction of two separate religious pagodas, one in Yangon and one in Mandalay. These pagodas are dedicated to housing the two copies of the Sacred Tooth and Anawrathafs Buddha image. Thus the legacy of the Sacred Tooth has been established both in the gcenterh and in the north.

The travels of the Sacred Tooth not only established new ritual fields of merit at crucial locations within the nation, but also engendered countless pilgrimages to the sites of its temporary residence. These pilgrimages were undertaken both by client groups within the boundaries of Burma itself and by transnational pilgrims. These pilgrimages mobilized large numbers of diverse social groups and formalized complex ritual patterns of patronage that obligated pilgrims to the elites of the SLORC-dominated state. Groups of pilgrims from relatively local origins included religious associations formed at the statefs instigation.

Other groups were constituted by classes of civil servants in government offices, neighborhood collectives, business people, and groups of professionals, such as medical specialists, and teachers and students from institutions of higher education. Pilgrims who journeyed from a greater distance tended to be leaders of ethnic minorities who resided in the more remote hill country. The ethnic groups represented included the Wa, Kachin, Palaung, Pa-O, the Shan, and the Lisu. Among these pilgrims were also Chinese (particularly Chinese with connections to Yunnan) and Indians (mostly Hindus) living in Burma. Each of these groups of pilgrims traveled to venerate the Buddhafs remains and to donate significant amounts of money that they, their families, and their communities had collected to meet their obligations to participate in the statefs ritual patronage.

Another cycle of pilgrimages was created by Buddhists from abroad who visited Myanma during this time period. The protocol for highprofile visitors prescribed the veneration of both the Sacred Tooth and other Burmese reliquaries. In addition to the Chinese Mahayana, Tibetan, and Yunnanese Theravada monks who accompanied the relic, lay and monastic delegations arrived from South Korea and Laos. Cultural exchanges featured Russian novices who received ordinations and attended Buddhist training courses in Burma.

Burmese missionary monks living in Calcutta, Bodh Gaya (the site of the Buddhafs Enlightenment in northern India), and Sri Lanka returned to Myanma to pay homage to the relic and accept honors awarded to them by the MahaNayaka Council and the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Prominently featured was a pilgrimage group led by a Burmese monk living in Singapore who was affiliatedwith Theravada communities in Penang, Malaysia, and Los Angeles. Together with one hundred lay Buddhists.many of whom were Singapore citizens of Chinese descent.he toured many historically and religiously significant sites in Burma. A similarly grand tour was also arranged for the senior members of the Chinese monastic delegation.

4. In 1994, though the official exchange rate gave a much higher value to the kyat, 200 kyat were roughly equivalent in purchasing power to one American dollar. 5. Officially, a minimum of 5,000 kyat was required for inclusion of onefs name among the published lists of donors. In actuality, however, donations made by families or other private citizens typically amounted to at least twice that amount. Donations collected Patterns of Patronage

The Sacred Toothfs sojourn in Myanma engaged massive donation drives marked by the politics of giving in national and transnational contexts. Each day, the New Light of Myanmar (NLM) conspicuously depicted donation rituals, reported exact amounts donated by individuals and collectives, and featured both donors and SLORC functionaries who officiated as ritual recipients of such donations. The newspapers published daily lists of donors and amounts they contributed in excess of 5,000 kyats.4 Also published were tallies of funds received each day and the accumulated totals to date. Altogether, the donations collected during the procession of the Sacred Tooth exceeded 162 million kyat and 13,700 pieces of jewelry.

On June 5, the day prior to the relicfs return to China, the NLM reported:

Todayfs donations included over 5.81 million kyats by pilgrims, 244 US dollars, 520 (Thai) bhat, ten Bangladesh taka, 65 Indian rupees, 4 Jamaican dollars, 1,100 Brazilian cruzeiros, 276 Chinese yans and three jiaos, 1,000 Indonesian rupias, four Singapore dollars, five Israeli shekels, five Nigeria nairas and 20 kobos, ten Philippines pesos, 250 Taiwan dollars, 650 Cambodian riel, two Venezuela bolivar, 1,000 won and three Malayasian dollars.

Such detailed accounts of monies were intended to attest not only to accurate bookkeeping. At a symbolic level, they were intended to legitimate the State Law and Order Restoration Councilfs ritual sponsorship and hence its religious patronage over national and international communities of Buddhists paying homage to the Tooth Relic. While the largest portions of funds were raised by collectives and the general public, a considerable portion was received from major private donors.

The list of donors provided a rough profile of the economic and political elite. Prominent members of the government and of the business community made significant donations on several occasions. Some business families donated as much as 100,000 kyats. A second group of major donors included representatives of professional and ethnic religious associations whose collective donations exceeded the required minimum through organizations tended to be less predictable, but often exceeded most individual donations.

The contributions of a third group also featured in the press comprised those who volunteered their services to facilitate crowd management and provide first aid, fans, and soft drinks to exhausted pilgrims waiting for many hours in long lines to pay homage to the relic. A fourth group consisted of foreign dignitaries from religious, economic, or political backgrounds whose large public donations were especially lauded in the press. A number of foreign political dignitaries who visited Myanma during this period, such as the prime minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the Indonesian foreign minister, the Yunnanese governor, and a military advisor from India made donations to a variety of religious causes.

The state provided donors with certificates of honor and arranged for select groups of donors to perform daily rituals to share merit and to acknowledge their ritual participation. These ceremonies were performed at the sites of the relicfs temporary residence at Kaba Aye in Yangon and at the State Pariyatti Monastic University in Mandalay. While such membership entitles one to privileges, it also entails continuing obligations to the patronage of a political elite. Public portrayals of generosity in support of a renewed Burmese national ethos suggest implicit competition among donors for political recognition and can be seen as a demonstration of onefs allegiance to prevailing power structures. Despite the large-scale public outpouring of generosity, the perception prevailed that contributions furnished access to political power and involved more or less formalized membership in a ritual community under the auspices of SLORC.

Traditional and Modern Contexts of Interpretation The recent ritual procession of the Sacred Tooth in Burma can be interpreted against the background of the textual and historical themes in the Theravada tradition. In traditional Theravada polities, the popular veneration of Buddhist sacred objects like relics and images was shaped by mythic constructs that often are modeled after texts like the Mahaparinibbana Sutta which tells the story of the Buddhafs cremation and distribution of his relics to the kings of surrounding kingdoms. A theme reflecting the righteousness of Buddhist rulers is also found in the Cakkavatti Sihanada Suttanta where the Buddha tells the story of a world conquering cakkavatti (wheel-turning) king whose reign is established through the submission of lesser rulers who voluntarily become his vassals.

Since this king possesses and rules by the Cakka, which is the Wheel of the Dhamma (Truth or Law), the well-being and prosperity of his realm is assured. Theravada myths and mythological histories include numerous stories of many kings who honor particularly potent relics (such as the famous Tooth Relic in Sri Lanka), give special veneration to particularly powerful images (such as the Emerald Buddha in Thailand), and construct highly impressive monuments (for example, the 84,000 stupas or funeral mounds constructed.according to the legends. by King Asoka, the great patron of Buddhism in ancient India). Living memory also recalls an earlier, government-sponsored visit of the Chinese Sacred Tooth to Burma and Sri Lanka at the time when Theravadins were celebrating the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of Buddhism.

The veneration of the Buddhafs physical remains (dhatu) is integral to the practice of cosmological Theravada Buddhism in traditional Buddhist kingdoms. A significant aspect of popular Theravada practice, relic veneration, the construction of stupas, or, more generally, state patronage of the Buddhafs rupakaya create a field of merit and source of political legitimation separate and distinct from merit made through giving to the sangha. These practices also establish a socially and ritually differentiated hegemony within which power relations are negotiated and consolidated.

First, relics and similar sacred objects stand for the entire body of the Buddha and, by extension, the totality of his dispensation. They map a cosmic center and establish structural orders between a microcosm, its periphery, and an encompassing macrocosm, thus linking, for example, the Southeast Asian periphery to the universal Buddhist order of things (dhamma). Secondly, a teleological significance is attributed to the presence of relics in a given location by mytho-historic narratives that link the historical present to a pristine time in the life of the Buddha.

Sacred realities are thus mapped onto temporal polities, and ritual acts localize the Buddhafs presence in cosmological, social, and political domains to generate merit for the eventual transcendence of this world (samsara) and attainment of enlightenment (nibbana). Thirdly, the ritual veneration of relics engenders a hierarchically ordered, religio-political community. It endows social actors with charisma and historical events with significance beyond the immediate contexts of cultural performance. A just ruler (dhammaraja) acts as ritual patron of some of the traditionfs most evocative root metaphors. He does so within the ritual and social structures of an economy of merit. Homage and generosity (dana) toward the Buddhafs spiritual and material remains are seen as indications of religiosity, social status, and political legitimacy.

Yet, 1994 in Myanma no longer denotes a time in which traditional, cosmological Buddhism is deployed in the context of a pre-modern religious and political ethos. The ritual structures created by the procession of the Chinese Sacred Tooth throughout the nation encompass multiple interpretations framed by competing contexts, including the contemporary and frequently contested notions of Burmese history, culture, and national community. The SLORC military clique seeks to strengthen its hegemony through patronage of the Chinese Tooth Relic, through the creation of historically linked and socially overlapping fields of merit throughout the contemporary nation-state of Myanma, a process that necessarily involves the mobilization of diverse communities and resources.

The statefs appeal to the symbols of cosmological Buddhism in a modern setting aims to create a particular ethos and vision of the Burmese nation, its history, culture, and territory.an ethos and vision that are depicted as, at the same time, gessentiallyh Burmese and gessentiallyh Buddhist. The state seeks to project to its citizens and to outside observers an ethos and vision of Buddhism in which the state, the sangha, and the laity speak in a single voice, emphasizing righteousness, scripturalism, and morality (sila).

While the rituals described here may be modeled after traditional paradigms rooted in cosmological Buddhism, in modern contexts competing visions of authority contest traditional orders and provide alternate avenues for interpretation. Some, though by no means all, of the competing Burmese interpretations share salient presumptions about the veneration of the Buddhafs relics and its social import. The range of ritual interpretations encountered only underscores the cultural and symbolic significance of relics as root metaphors of the Theravada Buddhist tradition.

Voices that speak withinMyanmafs national boundaries for alternative visions of Buddhism, the nation, and moral authority have become seriously muted. As the state controls social discourse about public meritmaking, alternate voices must be gleaned from silence, in absence from ritual participation, and in the countertexts of expatriate communities beyond Myanmafs national boundaries. Burma has a long-standing tradition of voicing political dissent in religious terms. In recent years, this has sometimes taken the form of disparaging remarks about the legitimacy and splendor of the grand Mahawizaya Pagoda built by the preceding Ne Win government next to Shwedagon Pagoda, a national symbol of Burma.

Others may ruminate about the stupafs night-lit silhouette serving as a backdrop for entertaining foreign businessmen in posh restaurants that have opened in this part of Yangon. Voices of dissent also emerge from religious donations that circumvent the statefs collection network. Especially among dissident elites, political resentment is expressed in perfunctory donations to the statefs religious causes, while more generous offerings are made to sources of merit that reflect a personal choice and are deemed more worthy of support.

Widespread mobilization of donations to state-sponsored religious causes has at times reinforced popular resentment as some consider it to be merely another form of taxation. The government-dominated media responds to such everyday forms of resistance mostly with silence. Outside the nationfs territory, some expatriate voices expressed doubts about the use of the donations that are collected. Some.including Buddhists who are historically aware.question the authenticity of the relic and its supposed connections to Burma and the Burmese tradition. While Burmese have traditionally venerated various Buddhist relics, issues such as these are being raised with increasing frequency in the present social and political contexts.

In conclusion, it is worth emphasizing that the many forms of venerating the Buddhafs relics are primarily individual acts of meditative devotion or ritual service with little relevance to the type of social interpretation discussed above.Historically, however, Theravada Buddhist culture established or perpetuated hegemonic structures through the construction and patronage of Buddhist relics and reliquaries. The perspectives that emerge from the modern Burmese Buddhist relic veneration in large-scale state rituals show how sacred objects can legitimate a specific vision of authority over diverse communities, and how such rituals can become a focal point for the articulation of national culture, history, and community.

Some general observations emerge. The first concerns the role of relics as root metaphors that evoke conceptions of power universal to the Buddhist tradition. As root metaphors, relics exhibit universal relevance across the tradition that can be gtranslatedh into specific local contexts and cultures sharing the same religious heritage. Universal conceptions become particularized in social, political, and historic contexts. A second commonality in the interpretation of relics as root meta

phors rests in the transformation of ritual service to the Buddhafs remains into particular patterns of political patronage. In state rituals, they support the creation of fields of merit, status, and power and are therefore readily appropriated by political ideologies and in the mobilization of ritual clients. They often become, as they have in contemporary Myanma, important currency in the economy of power. Figure 4. A scene from the Vessantara Jataka in which Prince Vessantara, Maddi, and their two children walk to their forest hermitage. A mural from Wat Luang monastery in Laos. Photograph by Donald K.

The essay in this chapter was taken from S. J. Tambiah, Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-east Thailand (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 160 .68. Copyright c Cambridge University Press, 1970. Reprinted with the permission of the Cambridge University Press.