The Esoteric Buddha and the Lotus-Born Guru

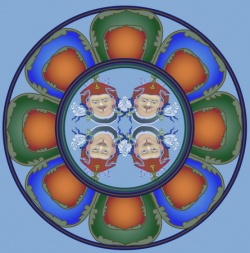

For 2,500 years Buddhists have considered with awe the achievement of Siddhartha Gautama. What induces such tremendous respect in them is not just that he gained Enlightenment, but that he did so without a teacher. (He learned meditation from Arada Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra, but neither of them could show him the way to escape from suffering - that he had to discover unaided.) Contemplating the difficulties that the Buddha had to overcome has given Buddhism a very great appreciation of the value of a spiritual teacher. As Buddhism developed, and the three yanas unfolded, the role and significance of the spiritual teacher changed. In the first two yanas the teacher may act as a preceptor, responsible for introducing you to the Buddha way, or as a kalyana mitra - a spiritual friend. The kalyana mitra is like an older brother or sister in the Dharma, who helps, advises, and encourages. In the Vajrayana, the teacher transforms into the vajraguru. The relationship with a Tantric teacher is a samaya, or bond, at least as binding as that between the meditator and the Buddha or Bodhisattva that he or she visualizes. In Tantra it is said that all blessings spring from the guru. The relationship is more like that of a doctor with a patient who desperately wants a cure and has total belief in the doctor's method. The guru is a vajraguru partly because everything in the Tantra is vajra everything is seen as an expression of the ineffable Reality of which the vajra is the chief Tantric symbol. The vajra prefix implies that the guru embodies Reality. He may formally teach the Dharma or he may not. However, just what he is expresses Reality. His being and mode of living are themselves a teaching. For his disciple, the communication of the Tantric guru may come as a thunderbolt. The vajraguru is spiritually ruthless. He is the teacher who will stop at nothing to awaken his disciple from the slumber of samsara. There are many stories in the Tantra, as in Zen, of gurus using drastic methods to get through to their disciples. For the Tantric disciple, the guru's kindness can never be repaid. Through initiation the guru bestows practices which can propel the student rapidly to Buddhahood. The guru is the source, the fountainhead, of all his or her development. In fact, for the Tantra, particularly Highest Tantra, the guru is a Buddha. Ideally the guru should be Enlightened. Tantric initiation partly symbolizes the empowering of a far-advanced Bodhisattva with the full qualities of an Awakened One. Most gurus fall a long way short of full Enlightenment. Nonetheless, the Tantra is concerned with finding correlates in actual experience for the highest values of the spiritual path. As we saw in Chapter One, it says, in effect, 'If you are not in direct contact with a Buddha, who in your present experience comes closest to that level?' The answer is, of course, your guru. So the guru becomes what is called the 'esoteric' Buddha Refuge. It is esoteric not in the sense of secret, but because it is not an experience that everyone can share. It is only if you enter into a close, devoted relationship with a teacher that he begins to function as a Buddha Refuge for you. It is also esoteric in the sense that it depends on an inner mental effort to see the guru in this way. Having received Tantric initiation from a teacher, the initiate is urged to make every effort to see the teacher as a fully Enlightened Buddha. He or she must disregard any apparent faults they may perceive in him or, rather, should attribute them to the impurity of their own mind. The Tantra holds firmly to the view that mind is king. If you see the guru as an ordinary person, you will receive the blessing of an ordinary person. If you see him as a Buddha, for you he will act as a Buddha, and your relationship with him will lead you quickly to Enlightenment. Each school of Tibetan Buddhism has certain teachers whom it particularly reveres as the founders of its school, or for starting a particular lineage of teaching or initiation. Although they are historical figures, over the course of time they have taken on an archetypal significance. These teachers are frequently visualized, either during the practice of Guru Yoga or as part of the Refuge assemblies that we shall be looking at in Chapter Eight. We shall now look briefly at a few of the most important of these gurus. (As usual, the number of figures one could describe is enormous.) We are going to begin by returning to the earliest sources of Tibetan Buddhism, to meet a figure who perhaps established an image of the vajraguru in the Tibetan mind, an image that helped to condition their understanding of the role of the Tantric guru in general. This is Padmasambhava ('lotus-born one'), known generally in Tibet as Guru Rimpoche ('precious guru'), and regarded as the founder of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. We shall take him as an example of a vajraguru, describe some of his many forms, and say a little about how he can be meditated upon. This should convey something of the immense richness of symbolism and association surrounding these guru figures, built up over centuries of devotion. Padmasambhava is a particularly complex 'spiritual personality', but in principle I could have taken almost any of the other gurus described in this chapter as examples of the multifaceted nature of the guru in the Vajrayana. Padmasambhava was instrumental in establishing Buddhism in Tibet in the eighth century. At that time King Trisong Detsen wanted to strengthen Buddhism, but was faced with fierce opposition from the Bonpos - followers of the indigenous shamanistic religion, led by a minister called Ma Zhang. A Buddhist abbot called Santaraksita was persuaded to come from Nepal, but though he achieved a certain amount, he could not overcome the Bonpos single-handed. They had been using witchcraft against him, so he recommended that the king invite Padmasambhava who, as well as being a master of Buddhist scholarship, was also a siddha, an adept in the psychic powers engendered by Tantric meditation. Padmasambhava came to Tibet, and the great monastery of Samye was built with his assistance. He is represented subduing the local deities of Tibet by his magic power, and binding them by oath to be servants and protectors of the Dharma. There exists a truly extraordinary biography of Padmasambhava called The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava. It describes how he is born as an emanation of the Buddha Amitabha, appearing spontaneously in a lotus on a lake in the country of Uddiyana. He is brought up by the king of that country as though he were his own son. Then, deciding it is time to leave the worldly life, he goes forth as a bhikshu. He studies all aspects of Buddhism, as well as medicine and astrology. Next, he spends years meditating in all the great cremation grounds of India and the Himalayas. We are given graphic descriptions of the unspeakable horrors of these places. They are symbols for the endless fearful sufferings of conditioned existence itself. Yet in all these places Padmasambhava meditates unafraid, and converts the dakinis - who, if you understand the text literally, are flesh-eating demonesses. In a cemetery called Mysterious Paths of Beatitude he is initiated by an Enlightened dakini and receives supreme knowledge. All through his life he is a controversial figure. On at least two occasions his flouting of convention causes such outrage that people attempt to burn him to death. Yet each time he emerges unscathed - rising phoenixlike from the flames. After performing his work of conversion in Tibet, he flies away to the land of the Raksasas (a race of ogres) to convert them too. Padmasambhava's biography is of an unequalled richness. It is one of the great spiritual documents of mankind. Within it, inner and outer events are so fused that it is frequently impossible to decide on what level of reality the events described took place. Are we watching actual events in the outside world - events which to us seem preternatural? Are we reliving Padmasambhava's visionary experiences? Is he - are we - dreaming? As presented in his life story, Padmasambhava becomes a kind of portmanteau figure - the embodiment in one person of all the accumulated knowledge, wisdom, love, and power of the Buddhist tradition. He is a master of all secular arts and sciences, as well as of all three yanas of Buddhism. In this way he represents the guru par excellence, for a guru prepares himself for his task of communicating the Dharma by first making himself a receptacle of the Buddhist tradition. From his teachers he receives the nectar of the Dharma, handed down from teacher to disciple ever since Sakyamuni managed to communicate it to Kaundinya in the Deer Park at Sarnath. I am reminded of a scene from an old Hollywood film, in which at a party of the rich and famous there was a great pyramid of champagne glasses. A liveried waiter arrived with a great bottle of champagne and kept pouring it into the top glass. When this was full it overflowed, and the bubbling liquid filled each tier of glasses, down and down in a foaming cascade. It is as though Sakyamuni Buddha is the top glass, who has made himself open to the transcendental. However, anyone who has absorbed the champagne brilliance of the Dharma cannot help but let it flow down to others. In this way, lineages of teaching are created. Padmasambhava represents the confluence of all these lineages - he is like a great crystal chalice in which all the bubbling streams of the Dharma meet. His life is also a symbolic recapitulation of the spread of the teaching. His transformations are its new developments. In the course of his story he takes on numerous different forms, and at each stage, with each fresh metamorphosis, he acquires a new name. In this way he reminds us of two aspects of the guru. First, any guru worthy of the title has pursued his own development unremittingly. He has been prepared to undergo a number of spiritual deaths, and complete reorientations of consciousness, in his pursuit of the goal. The guru too, among his secondary characteristics, is a namer. In many cultures, entering a new stage of life entails a change of name. It is the guru who acts as guide as you enter upon the different stages of the spiritual path. Often, the guru will confer a new name upon you as you do so. This happens when you formally go for Refuge - when you ceremonially commit yourself to the Buddhist path. It happens if you leave home for the homeless life of a bhikshu or bhikshuni. It very often happens when you enter the mandala of the Vajrayana. In order to name something you have to understand its true Another similar form appears, this time with natural skin colouring. He too wears royal attire and holds the damaru in his right hand. In his left he usually has a skull cup. In his belt is uphurba, a kind of magic dagger. This is much used in Nyingma Tantric ritual. It was originally more like a peg or nail for pinning down demons and hindering psychic forces. It gradually became stylized into a three-edged blade ending in a point. The blade emerges from the body of a garuda. This implement embodies the power of a Tantric deity called Vajraklla.27 The phurba is often shown crowned with the head of Hayagriva, a protector of the Dharma whom we shall encounter in Chapter Seven. The name of this manifestation is Lodan Choksey ('wise seeker of excellence'). Next, Padmasambhava enters the cremation ground, sits in meditation with his back to a stupa (or reliquary), and becomes Nyima Odzer ('sunrays guru'). This is Padmasambhava as siddha and yogin. He wears only a loincloth of tiger skin, a meditation sash, and a crown of skulls. Yellow light radiates from his body. His hair, combed upwards, is crowned with a vajra. In his right hand he holds a trident staff. With his left hand he plays with the rays of the sun. This recalls an incident in his life story in which Padmasambhava caused the sun to halt in its tracks. He had made an agreement with a wine-seller to drink as much as he wanted and settle the bill at sunset. After seven days the sun still had not set. This is a good example of Tantric practice being bodied forth in legend. It has nothing whatever to do with alcohol. Rather it symbolizes Padmasambhava's entry into a state of consciousness in which time stands still, the mind and subtle psychic energies come to rest, and the yogin enjoys the mahasukha - or Great Bliss - uninterruptedly. The figures become wilder and more awe-inspiring. Next there appears a wrathful manifestation, Guru Senge Dradok ('one who teaches with a lion's voice'). He also wears a crown of skulls and a tiger skin. His body is circled by a necklace of skulls, his face contorted with fury. He brandishes a thunderbolt sceptre, and tramples underfoot forces inimical to the Dharma. Lastly we come face to face with Dorje Drolo ('immutable guru with loose-hanging stomach'). He rides through the jungle of life on a tigress. His expression is ferocious, and he is enhaloed with flames. His massive dark brown body is garlanded with skulls. He waves a thunderbolt in his right hand, and points a phurba with his left, to ward off all threatening forces. This is Padmasambhava as subduer of demons. These are eight of the forms that Padmasambhava assumes. They could be said to represent the guru's resourcefulness in transforming his approach to each situation, so as to teach in an appropriate way. He is not fixed in any mode of being or acting. Knowing that his nature is as empty as the blue sky, he can shift shape spiritually and psychologically, like clouds sculpting themselves into different forms and then dissolving. For stubborn-minded enemies of the Dharma, the guru musters even more power and energy; for those open to the sutras he teaches sutras; for those ready for the mysteries of Tantra he demonstrates Tantra. In this way he exemplifies upaya, or skilful means - the flexibility of the Buddhist teacher. Padmasambhava's eight forms could also be seen as the same principle at work on different levels of consciousness. To the rational mind the guru appears as a pandit or a Buddha, and proclaims teachings on the Four Noble Truths and so forth. However, deeper more primitive strata of the mind are not amenable to being taught in this way. These aboriginal levels of consciousness need to be converted through the magic powers of figures like Nyima Odzer and Dorje Drolo. In summary, we can say that these differing manifestations mark Padmasambhava as the embodiment of all the resourcefulness of Buddhist teaching. They show him as the typical Tantric guru - working through logic and reasoning to convert the rational mind, but also diving deep into the psychic depths to confront, subdue, and transform the powerful and primitive - perhaps even demonic - energies that inhabit those dark realms. Though we have looked at so many forms, we have yet to meet Padmasambhava in his most frequent manifestation, as a king of Zahor. In a sense you most truly meet a vajraguru when you receive initiation from him. So we shall try to venture out into the unknown to meet the Precious Guru, and be empowered with his knowledge, power, and compassion. We shall ask him to grant us siddhi, both mundane powers and the supreme siddhi of Enlightenment. These powers are emphasized in Padmasambhava's mantra: om ah hum vajraguru padma siddhi hum. To meet him we have to go to the place of initiation, to enter his secret realm. His realm, in which he flies like a great eagle, is the blue sky of sunyata. Initiation can only take place if we let drop our barriers and habitual ways of being, forsake our own territory, and enter the state of spiritual openness. In the vast blue sky appears a fiery-red lotus. On the lotus is a red sun disc (symbol of compassionate skilful means) lying horizontal; on the sun disc a white moon mat (symbol of the wisdom of realizing Emptiness). We wait, expectant. The lotus throne and sun and moon mats are like a great stage, on which the hero of a cosmic drama will appear. The blue sky above the moon mat begins to glow with brilliant light. The radiance gradually takes form, until we see a blissful young man seated before us. (This is how he usually appears, though sometimes he can manifest instantaneously, from a dazzling bolt of lightning.) He is dressed in robes.2 The outermost is a beautifully decorated red cloak. This symbolizes the Mahayana. It is outermost because it is love and compassion which the Precious Guru offers to the world in all situations. Beneath the red cloak he wears the yellow robes of a monk showing that though he follows the Tantric path beyond conceptual distinctions of right and wrong, he keeps pure his ethical discipline. He has not abandoned the basics of Buddhism, but simply carried them up into a higher vision. Beneath these he wears a blue robe. Blue was the royal colour in ancient India. It became associated with the Tantra, as it incorporated much of the symbolism of royalty into its ritual. For example, we have seen that the Tantric initiation procedure in which the initiate is sprinkled with water from an initiation vase by the guru parallels the ceremony of anointing a king. So the blue robe which Padmasambhava wears, most hidden and closest to his heart, symbolizes the Vajrayana. He wears Tibetan-style boots, and sits totally relaxed, his left foot tucked up, his right resting at a loose angle. His right hand rests on his right knee, holding the vajra of Truth itself. He clasps it with his middle fingers, while his index and little fingers are outstretched, in the mudra of warding off demons and enemies of the Dharma. It is said that Padmasambhava's power increases as worldly conditions deteriorate. He is the supreme alchemist, the master who transforms hatred into wisdom, craving into love, darkness into light. The more powerful the forces of evil become, the more lustrous his form appears. In the depths of despair and annihilation, his diamond wisdom shines like a great lamp. Difficulties, opposition, and danger fuel his spiritual power. In his left hand he holds a skull cup filled with something that looks suspiciously like blood. The skull cup represents sunyata, and the liquid it contains is the amrit-nectar of Great Bliss. With the realization of the emptiness of self and others, a revolution takes place in our experience. The forces of desire, which caused us so much restlessness and pain, now give us bliss. The problem with pleasure is that we usually experience it within the framework of subject and object. It reinforces our feeling of being an 'I', 'in here', trying to incorporate a pleasurable stimulus 'out there'. The result is craving and frustration. When self and other dissolve away, there is just enjoyment, with no attempt to nail it down, or strangle it by repetition. William Blake well sums up the difference:

He who binds to himself a Joy Doth the winged life destroy; But he who kisses the Joy as it flies Lives in Eternity's sunrise.

The skull cup symbolizes the death of the ego, the spiritual death which creates space - the experience of the 'open dimension' of sunyata. The nectar is like blood, for blood is life, the free-flowing energy capable of assuming any form , which is released with Insight. In Nyingma circles this ambrosia - the Great Bliss experience - is often symbolized, for obvious reasons, by beer or wine. Rising up out of the skull cup is a vase of the Nectar of Immortality. Above it is a precious jewel - the wishfulfilling gem of the Bodhicitta.

In the crook of Padmasambhava's left arm nestles a trident staff, known as a khatvanga. It is adorned with a number of strange objects. A damaru hangs from it. There are crossed vajras. Above them is a vase of initiation adorned with victory pennants. Then there are three human heads: one freshly severed, one decomposing, the top one just a skull. Finally, the staff is surmounted by a flaming trident. The net of symbolic associations surrounding the different elements of the staff is complex, and we do not have space to discuss them individually. We shall look at just two aspects of the staff overall. The first is that the staff is spoken of as the hidden consort. According to the biography of Yeshe Tsogyal, who was one of Padmasambhava's chief female disciples, at one point the Precious Guru wanted to travel with her, without her being seen, so he magically transformed her into his staff.30 Thus the khatvanga symbolizes all the spiritual qualities that the Vajrayana associates with the feminine (principal among which is wisdom).

Padmasambhava's holding the staff indicates that he has perfectly integrated these qualities. Also, the khatvanga is a magic staff, and Padmasambhava is the peerless spiritual magician. It was through his magic powers that he defeated the Bon shamans and subdued the demons of Tibet. Through his sadhana you magically transform yourself, turning the base metal of your mundane consciousness, the lead of ignorance, into the gold and jewels of Tantric attainment.

On his head the Precious Guru wears a lotus cap - red in colour. It is one of many hundreds of kinds of hat to be found in the Tantra - each with its own particular significance. This one has flaps which can come down over the ears. On its front are five jewels, arranged in a mandala pattern - white in the centre, blue, yellow, red, and green around - symbolizing the five wisdoms. Above them is a crescent moon surmounted by a golden sun. These symbolize the subtle energies of the psychophysical organism, which Padmasambhava has unified, thereby bringing an end to all dualistic thoughts. The cap is crowned with a half vajra with a vulture's feather rising out of it. The vulture is a bird associated with yogins - because it is said to be the bird that flies the highest.

Padmasambhava wears ornate earrings, and a priceless necklace of jewels. He has long flowing locks, a moustache, and a small pointed beard. His gaze is piercing. His face has a strange expression, a kind of compassionate smile, but tinged with wrathfulness. His smile is a challenge. We can say that it symbolizes the union of compassion (the smile) and wisdom (the wrathful gaze), but that does not explain it away. This wrathful smile is a key to understanding Padmasambhava. It is mysterious and unfathomable. Sometimes when his visualization dissolves I am left with the after-image of that dangerous smile, hanging in the sky like an Enlightened version of the Cheshire Cat. But, if Padmasambhava is a cat at all, he is a leopard or tiger of the Dharma. His body is adorned with what are called his three vajras: a white om at his forehead, a fiery red ah at his throat, and a deep-blue hum at his heart. They are like three special concentrations of Padmasambhava's immense spiritual power. It is from them that, if one is ready to run the gauntlet of the blue sky and dare that dangerous smile, one will receive the Precious Guru's initiation, be empowered with both mundane siddhis and the supreme siddhi of Enlightenment itself, and become a king or queen of the Dharma.