Theory and Practice of Guru-Yoga

Alexander Berzin

Munich, Germany, July 2004

Session Two: The Seven-Part Practice

Unedited Transcript

Question: [inaudible]

Alex: Okay, the question is about root gurus. What happens when we have several of them, and one that’s especially inspiring? And isn’t the root guru the one who gives us initiation, tantric initiations and transmissions and discourses?

We can certainly have many teachers. And we can possibly also have more than one root guru. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama said, we shouldn’t see the various spiritual masters that we have as contradictory. But one way to look at them would be like the eleven-faced Avalokiteshvara, that all of these different faces of the different teachers that we have all fit together into one figure. This is a nice way of looking at them. Of course what that precludes is that if we have one question, we ask the same thing to each of our teachers, because, undoubtedly, they’re each going to give us a different answer. And so that can be confusing. So that’s not too wise to do. But especially in terms of advice about what would be best for us to do, don’t ask more than one. They’ll definitely tell us two different things.

Although in the optimal case the root guru would be the one that gives us the tantric initiations, etc., that is not necessarily the case. The root guru isn’t necessarily our first teacher. It’s not necessarily the teacher that we received the most teachings from. It is the one that moves us the most, inspires us the most. And there can be more than one. You don’t actually have to grade them on a scale – and this one I give 73 on the scale, and this one I give 71, so 73 is my root guru. One interesting sign, by the way, is which gurus appear frequently in our dreams. That is a good sign in terms of who really do we have such a deep connection and feeling toward.

In the Gelug tradition, there is what is known as the Guru Puja (Lama Chopa) which is a wonderful practice. And this, which most people do every day, by the way, especially if you have received teachings on it, then the commitment is just to do it every day. And in that, you don’t have to do it at a deathly slow speed so that it takes two hours – if one does it quickly, it only takes about five minutes to do. The main visualization in it is the tree of assembled gurus. And in that visualization, of course, you have all the lineage gurus. But for most of us we don’t know the biographies of these various lineage masters, and so reciting a list of names doesn’t move us very much. You don’t actually recite the names in that practice, in any case. What is part of that visualization is one cluster of figures – and there’s hundreds of figures in this visualization, it’s incredibly complex – but one of the clusters of figures is of all our spiritual teachers, personal spiritual teachers. And this I find very, very helpful. And so what you do (at least what I do) is that you arrange them. So you arrange the various teachers that you’ve had during this lifetime, and you think of the spiritual teachers, and you think not only of the spiritual teachers (from the various lineages, or whatever, that we study with), but those who have taught us something that is part of our spiritual path. And then also what’s good to include is those teachers who have taught us something that has been very useful in the spiritual path. For instance, those that taught us the various languages in which we can read the Dharma, whether it’s – if we’re German, the one who taught us English. Not absolutely every teacher, but one who is sort of representative, the main one.

In my case, I learned many Asian languages; so the main teacher for each of those Asian languages that I studied that I read the Dharma in. And from my regular education, the main teachers, not my third grade teacher and so on – although if you wanted to do it absolutely fully, you would – but the one who taught me to read, the one who gave me really a lot of inspiration in my university education, whether it was in philosophy, or psychology, or Asian history, or whatever. If I know the name mantra of the teacher – I know Sanskrit, so I can translate their names back into Sanskrit, but even if you don’t have that, it doesn’t matter. You just can say their name, just as a way of remembering them. And whether you can visualize it or not, it depends on our skill. You can recite their names and not just go, “Blah-blah-blah,” like that. But take a moment to think of what is the most outstanding good quality of this teacher, and what have I learned from them. How has that contributed to my present Dharma understanding and Dharma knowledge?

This is a very powerful, very, very helpful practice to do. That is a very good and important aspect of guru-yoga. I mean that you have to fill in the guru-yoga. You have a basis visualization that includes this, and you do have a certain part where you go through the various gurus’ name mantras – that’s where you add it to. And this is something that you can add in any of the guru-yoga practices. There are so many lineages and almost all of them have some sort of guru tree or refuge tree. You put it there. In connection with that, one of my teachers [[[Geshe]] Ngawang Dhargyey] said, “Look at us! If someone asks us how much money do we have in the bank, we can give them a figure instantly. If they ask us how many spiritual teachers have we had, we can’t give a number.” You don’t know. That shows us where our interest and priorities are. We have the tree of gurus, like the refuge tree, and you can fill it in there if you are not doing the Guru Puja, the Lama Chopa. Every tradition has something like that.

Question: Is it better to do several lineage trees if we have teachers from different lineages, or put them all together?

Alex: I put them all together. I arrange them in clusters, clusters from different traditions, like you would have on a tree – different branches. I don’t think it is very helpful to have them too separated from each other. The same with my Western teachers from my regular education – I have that as a separate thing – or my language teachers. This is just my own personal way. I think we need to be creative. Nothing artistic about it. My own way of doing it is in each cluster I have a central figure who is sort of the main one from that lineage, or the main one, let’s say, who taught me Tibetan. And then have around it the other teachers from that lineage, or who taught me the other Asian languages. That is just my own style. I think we need to be creative. That there’s room for creativity there – it is just an artistic thing. And even if we can’t visualize all of them simultaneously, which obviously is very difficult to do, then at least as we say each of their names and think of them for a moment, we can remember what they look like. It makes it more alive. The whole purpose of guru-yoga – not purpose, but the energy of guru-yoga comes from being alive. That is why it is so important to have had a real life teacher and not just learn from books. You don’t get energy from books, not very much; you get some, but not as much as from an actual person. It is different watching a person in a video and being in the same room with them.

Yes?

Question: [inaudible]

Alex: The question is about an inner voice and having inner communication with one’s spiritual teacher. She met a Western teacher who said that he was always in communication with his guru through inner communication. He didn’t need to see his teacher, or maybe the teacher was dead, I don’t know. But he didn’t need to see the teacher or go to teachers anymore. What is going on here?

Is his teacher still alive?

Participant: No.

Alex: He’s dead. Well, this is a difficult question to know because we don’t really know this other person, this Western teacher. I think that in some cases, but rare cases, there is such a thing as telepathy. It is certainly described in the texts. And so there must be something like that. But I doubt it’s like, “Guru to Alex, guru to Alex. Come in, please.” And then you hear the voice and they are giving us instructions. I can’t imagine that it is on such simplistic level as that.

From my own experience of my own teacher passing away, that often you feel much closer to the teacher after they have passed away simply because you can’t say, “Well my teacher is travelling somewhere else,” and so you give that excuse of saying we’re far apart, because really what one has to do is to internalize the teacher, internalize the values of the teacher.

And I certainly often – not so often – but when I am in a perplexing situation and I don’t quite know what to do, then I always ask myself, well, how would Serkong Rinpoche handle this situation? What would he do? What would His Holiness the Dalai Lama do? My two main teachers. What would he do in this situation? And then since I have had a lot of exposure to them in many, many situations, then I have some idea of how they would react. Are they communicating with me at that time? I don’t think so. Not directly, not consciously from their side. Now in most cases a great Tibetan spiritual teacher will have reincarnated, so who is communicating with whom? I don’t know. And in terms of telepathy, there are many different forms of telepathy. There is certainly a very deep connection by which you feel something. From another person you can feel their energy very easily even if they are not there. You can know that somebody is about to call you, “I was just thinking of you,” and then they call two seconds later. I’m sure many of us have experienced that.

And so there are these types of connections. But also there are those who might fall into the category of charlatan teachers, often Westerners, who want to impress others by saying, “Oh, I am in deep contact with my teacher all the time. My teacher is speaking to me,” whereas that’s only putting on an act. But it is very hard to tell what somebody else is doing. You have to look at other aspects of their behavior. But in general if one’s teacher is alive and one has access to the teacher, it is best to have contact with the teacher, and certainly in terms of explanations of things and learning more. Obviously there are those who have had visions. It is quite famous in which the vision of Maitreya, or whoever, has given them teachings. But that is very rare. It’s well-known, but I don’t think most of us are going to have that experience. But this experience of “How would my teacher deal with this situation?” – that, I think, is something that we can all work with. That’s what it means to have the guru in your heart. You internalize their values.

Sometimes we think that, “Oh, I was just thinking of you,” or “I had the feeling you were thinking of me,” and sometimes it’s true, sometimes it’s not true, if we check up with the person, “Were you thinking of me at such-and-such an hour?” So this type of experience is not reliable. Although they are well-known – many of the great texts that we have came from visions. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has spoken about these pure visions. He said that just as there have been pure visions and transmissions of teachings in that way in the past, there is no reason to say that it won’t continue in the future. So it will continue in the future, but he says that it is very important to test these teachings to make sure that they are not something which are garbage. And so one has to see is it consistent with all the other teachings of Buddha? When they are put into practice by qualified masters, do they bring their stage of the results and so on? And especially when teachings come from some sort of spirit or through an oracle or something like that, through channeling – this sort of thing – this is very, very important to check up. But just as there can be very beneficial highly developed spirits that can speak and give advice through oracles, there can also be very destructive spirits, evil ghosts (that sort of category) that likewise deceive people in terms of giving advice. So one always has to check these things, so His Holiness says.

So maybe this is enough for the question and answer session. Let’s have a tea break. We’ve gotten through the hour after lunch without too many people falling asleep. [laughter]

Let’s start the sutra level of guru-yoga, a type of meditation practice. As I said, this is quite important as a basis for tantra level practice with the elaborate visualizations. But even with the sutra level practice we can imagine various lights and so on coming to us. It is not necessarily exclusive to tantra level practice. But we need to realize that guru-yoga is basically one of the preliminaries, it’s a ngondro (sngon-'gro) practice. Basically, ngondro means preliminary practices. And so there are special preliminary practices which are shared in common between sutra and tantra and those which are exclusive to or special for tantra.

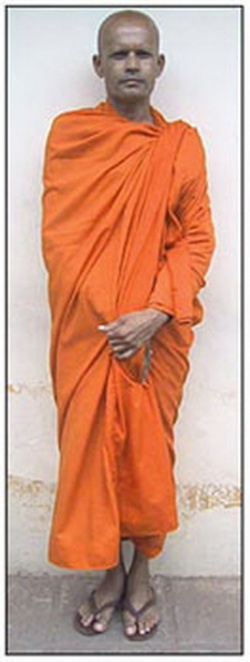

Now we start the practice by imagining our spiritual teachers or looking at photographs of them. I don’t think the point of such practice is to perfect our ability to visualize, and so if we can’t visualize very well, then having a picture of our spiritual teacher in front of us is perfectly fine; there’s nothing to be ashamed about with that. And if we look in the private rooms of most Tibetans, Tibetan monks and laypeople alike, but particularly the monastics, everybody has pictures of their teachers on the walls, on the tables, everywhere. This is quite helpful. Not in the bathroom, please – be respectful.

The practice I am going to describe, I must tell you that I have put it together pieces from here and there, from various sources. There is a great deal of discussion in the various sutra texts, particularly texts from the various Tibetan traditions, which (for want of a better word) we can put into the category of lam-rim, of graded stage teachings. And all of them teach about the relation with the spiritual teacher, and each of them have various practices to sort of put it together. I have this explained in my book Relating to a Spiritual Teacher. And this is primarily coming from the Kadam tradition. Many elements are found in the other traditions as well.

We start off with offering the spiritual teacher the seven-part practice – seven-part invocation, sometimes it is called – prostrating, making offerings, etc. This is the most standard, standard practice that everybody, absolutely everybody does for building up positive force. Its classic expression is found in Bodhicharyavatara (Engaging in Bodhisattva Behavior) by Shantideva. It begins with – I imagine most of you are familiar with it, but just to go briefly through it – it begins with offering prostration, which is showing respect, basically, with body, speech and mind. So physical prostration, recitation of some verses, and thinking of the good qualities, and showing respect to the good qualities. The practice, by the way, of course begins with, first, refuge or what I call “safe direction,” and bodhichitta – we always start the practice with that.

When we make prostration, what is very helpful is to think on three levels of what we are offering. The object to whom we are offering prostration is, on the one hand the Buddhas and the spiritual masters who have reached the goal (or embody the goal) that we are aiming towards. It’s very important to not just see this as some external thing that somebody else has achieved, which would then easily lead to just worshipping the guru: “You’re so wonderful. I’m so lowly and miserable. Just tell me what to do.” We certainly want to avoid that and so we also offer prostration, at the same time, to our own future enlightenment, our individual future enlightenment, which is further down the line of our mental continuum but which has not happened yet. Bodhichitta is focused on that future enlightenment with the intention to achieve it, based on having full confidence that it is possible and with the motivation and the aim to help everybody by means of that. You want to help everybody, that’s the motivation to get there; and what we want to do when we get there is actually help everybody. So we show respect to that enlightenment, not just to the enlightenment of the spiritual teacher, or then the guru relation is just worship of this wonderful being up there – that’s not what the relation with the spiritual teacher is about, it’s not healthy. Also we show respect with the prostration to our own Buddha-natures. It’s the Buddha-nature of the teacher that allowed the teacher to reach his or her high attainment, and it is also our own Buddha-nature, potentials and qualities, that will allow us to reach enlightenment.

So the entire relationship, I believe, with the spiritual teacher – it’s very important to have it based on respect. Not only respect for the teacher, but respect for ourselves, respect for our own spiritual path and what we are doing. Then it is followed in a mature and adult way. It is very important to have that guru-yoga and that relation with the guru be on an adult mature level. Not as a child, with a childish mentality. Of course we don’t want to go to the extreme of being arrogant either. Mature.

So the next thing is, the second of the seven-part practice, is making offerings. I am not just going to offer a kata or some incense to the teacher, who doesn’t need such things. I was pointing out yesterday what we are willing to give is everything to be able to reach enlightenment to benefit everybody else. And we are offering to the teacher as the conduit, as it were. Same thing with the Buddhas, it is a conduit to be able to reach that goal. So we have to offer very significant things, like our time and our energy, and our hearts, our enthusiasm. These type of things, not just some silly little box of incense that we bought.

Sometimes we read how I offer my spiritual teacher a mandala of my body, speech, and mind. That doesn’t mean abuse me sexually or whatever. Obviously not. What that means – and it doesn’t mean, “I am a mindless thing. Mold me and make me your slave.” But as I was expressing about myself with Serkong Rinpoche, “Please make a donkey like me into a human being.” Saying that: please help me to develop my way of acting with people (that’s the body), with communicating, my attitudes towards others, and so on, so that I can help them more. Help me to develop. I offer you these as the working materials to help me work and develop my body, speech and mind to have the qualities of a Buddha, which is what I am focusing on anew. It is a very significant offering, not to be done lightly. If you offer something, it means you really offer it. Not just give a little bit, and then when they start to actually use it and correct us, and stuff like that, we take it back.

What is a very useful set of offerings is the offerings of samadhi, it’s called, of concentration, which comes from the Sakya tradition, which is offering different aspects of our practice. What we are doing is we are thinking of various aspects of our practice, and we offer these. The guru doesn’t need these, the Buddha doesn’t need these either. As I said, they are a conduit; it’s through offering to them that we use it to help others. If I just give an example in my own case, everything you have read and studied, all the knowledge you have gained, these type of things – by offering it to my teacher in the sense that then I can be his translator. I use all my study through him to be able to translate for him and give it to others. In this way, I make an offering of all my talents, all my work, all my energy – through him to help others. And obviously there can be many other ways besides just being a teacher’s translator or secretary. Also it can be just trying to carry out his or her intentions, ideas, trying to help others, trying to do things. And each of these offerings takes a symbolic form of the traditional offering, but that is just making an image out of them. What we are actually offering are these various aspects of our practice. Or working in a Dharma center, whatever talents we have to help the spiritual teacher help others. We offer that. Or work in a hospital, or take care of disabled people, to carry on Buddhist type of work, which is what our teacher obviously wants everybody to be able to do.

So, as I say, it can be very wide scope. The traditional thing is everything we have read and studied – we offer that. That takes the form – it sort of coagulates in the meditation practice into the water offerings. The emphasis is not on the water. The teacher doesn’t need a bowl of water. What’s he going to do with a bowl of water? Feed a cat. Everything that we have read and studied; the water is just a symbol of it, a representation. And then all the knowledge that we have gained from our reading and study, these take the form of flowers, flowers that grow from the water. And then all the discipline that we use to put that knowledge into practice with meditation, with actually helping others, with restraining from acting negatively; a discipline to do whatever work we do to help others based on that knowledge that we have gained – this takes the form of the incense smoke.

Then the insight that we gained from that disciplined practice, that takes the form of light, the light of insight, light from butter lamps, candles, and so on – light the way for everybody. Then the firm conviction that we have in the Dharma, convinced that it is true, nothing can shake us – this firm conviction we offer in the form of refreshing cologne, so refreshing to everybody. You meet somebody who is free from doubts, who is firmly convinced – not a fanatic – but firmly convinced based on experience and insight and reason – very refreshing for everybody. A refreshing cologne – it was used in India, we’re not talking about something in the West; that is something from ancient India.

And then the concentration that we are able to gain with that firm conviction. A big problem with concentration is when we have doubt, we don’t really know, we are not sure of ourselves. When you have firm conviction, you are convinced of the correct understanding, then you can concentrate perfectly. It is so important for helping others. So we offer that concentration. And that concentration takes the form of food. Great meditators can live on their concentration; you can stay in deep concentration meditation for days and it sustains you, you don’t have to eat. It takes the form of food. And then, finally, our clear explanations of the Dharma, likewise our praises of the Dharma, our reading of the texts, and all these verbal things that we can do with this concentration and conviction and so on. The basis of all of these, particularly our ability to explain the Dharma clearly, this takes the form of beautiful music.

So this is the offerings of concentration. A wonderful practice, absolutely wonderful practice. It comes from, as I say, from the Sakya tradition. Chogyel Pagpa (Chos-rgyal ‘Phags-pa) was the master who developed it first, wrote it first. And he was a great Sakya master who brought Buddhism to the Mongols – to Kublai Khan. It was adopted in the Gelugpa tradition, and particularly during the Monlam festival in Lhasa, it became part of that. It is incorporated in the Kalachakra six-session practice. We find it in many places. Very helpful, very profound, very practical. It is not just to make these offerings of incense and so on – on one level you start thinking this is pretty trivial. They have a deeper meaning, deeper representation.

Although of course the offering of the incense, flowers, and so on – in that form – does have a deeper meaning in addition to this, in terms of bringing bliss to the various senses, which then in tantra has a deeper significance. But on the ordinary sutra level, it also has a deep significance in terms of these offerings of concentration. The tantra is the blissful aspect, the sutra is these concentration aspects. At the literal level, it’s what you do when you invite a guest to your home in ancient India and serve him a meal. That is the literal level.

So that’s the making of offerings.

The third of the seven-part practice is admitting our mistakes. So we admit our shortcomings: we’re lazy, don’t feel like practicing, etc. And we regret that, we really would not like to repeat that, and we reaffirm our foundations – refuge and bodhichitta. And whatever we learn with the teacher, and whatever we learn in general, we’re going to apply to overcome these shortcomings.

I think that here – again, this is my own addition now, so let’s be clear about that; it is not coming from original sources, but I think that it fits in very nicely here – to admit our own mistakes, also to acknowledge the wrongs that we might have experienced from less than perfect teachers. In other words, if we have been abused, if we have been deceived by charlatan type of teachers, to acknowledge that. That is very important, just on a psychological level. To acknowledge that, “Yes, this was terrible what happened. It was a mistake to get into that type of relationship. It was a mistake to follow that type of teacher. I regret it very much, but it happened. And yes, I was misled. I am going to try my best to not let that happen again, being much more critical and much more careful in the future. And I reaffirm what I am doing with my life – it is not that I am going to give up Dharma because of this. I reaffirm my safe direction of refuge and my bodhichitta aim. And whatever further things I learn in the Dharma, I am going to apply that so that I don’t repeat mistakes with future teachers, but just develop healthy relationships with proper teachers.” I think this fits in very nicely here and can help with the healing process of those of us who have been spiritually injured, as it were, from misleading or abusive teachers, because many people have experienced that. We need to deal with it – somehow heal the injuries and the pains, and not just ignore it. Openly admit it, especially if we want to do proper guru-yoga with a proper teacher afterwards. We don’t want this bad experience that we had in the past to undermine it because we haven’t really acknowledged it and dealt with it. Psychologically, I think it is valid to put it in here.

And just as when we think of our own shortcomings and feel regret, that means that we are not feeling guilty about it, “I’m not a bad person because of this, but I just regret that it happened.” Similarly, if we have been misused or abused or fooled by a charlatan teacher then, likewise, when we regret that – “I regret that it happened, it is really very sad, very unfortunate that it happened, it doesn’t mean that I am a bad person. It doesn’t mean that I need to feel guilty and punish myself because of that. I feel very bitter about that – that also would be inappropriate. It happened for various karmic reasons, obviously not all my fault and not all the teacher’s fault, but obviously some karmic connection with this person. And, okay, it happened, and it is very sad that it happened. Let’s purify whatever further karmic leftovers might be there so that it doesn’t happen again.” But none of this: “I’m a bad person,” and feeling guilty about it – that’s not going to help at all. And then the teacher, that they’re the Devil – that doesn’t help either. This makes us feel more bitter and more angry, and that doesn’t heal anything. It’s not that the teacher is the Devil.

So the fourth of the seven parts is rejoicing in the positive qualities and accomplishments of others and of ourselves. And so we rejoice in how wonderful it is that our teacher, the Buddhist teachers in general, have developed all their good qualities and have reached their stage. And we also rejoice in our own Buddha-natures. It is very important that we have the possibility to achieve the same, and we rejoice in whatever positive things we ourselves have already done which resulted in our being at this stage at which we are at. Because even if we are very inexperienced practitioners and not terribly advanced, this is far, far better than someone who has just negative attitudes toward spiritual practice in general. So obviously there is some positive karmic aftermath that is resulting in our being where we are now. So we should be very happy about that, positive about ourselves. And it’s feeling positive about the spiritual teacher. That also is very important – if we have been abused or had bad experiences with teachers, to reaffirm our own good qualities. We can see this seven-part practice is not at all something to be trivialized. It is very deep and profound and very helpful, not just to be rushed through and ignored as, well, beginner stuff. There is a great deal of wisdom behind it.

The next part is to request the teacher. It is so important, “My teacher, teach me. I really, really want to learn. I am open. I am ready. Teach me at all levels. Work on my personality, not just teach me some text to memorize.” The old Serkong Rinpoche used to like to go to the circus and particularly to see the trained animals. And he used to say afterwards, “If a bear can learn how to ride a bicycle, we as humans can learn much more than that.” So there is hope for us. And don’t just develop yourself to the level of what a bear or a dolphin can be taught – to do some tricks, and we get fish in the end as our reward. So we ask our teacher to teach us deep and significant things, not just to ride a bicycle like a bear. But I was using that example of, you know, at the end, if we have performed well for our teacher, he pats us on the head and we wag with our tail! That is not the point. Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey always used that example. I loved it.

The next limb is, “Teach me all the way to enlightenment. Don’t go away.” Very significant. We are not going to reach a point of saying, “Well, I have had enough already,” and back off. “I don’t want to go any further. I don’t want to hear more about voidness. I’ve had enough. My head is filled with that. It’s too much!” [Instead], “Don’t go away. Don’t ever – you know, I’m serious, I want to go all the way to enlightenment, and I’m never going to say I’ve had enough until I reach enlightenment. So, please, teach me the whole way. I’m serious, not just a (again Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey coined the phrase) Dharma tourist – coming to see just a little bit and then go back home.”

And then the seventh limb is the dedication, “Whatever positive force has built up from my practice, and so on, I don’t want that just to contribute to improving my samsara; I don’t want just to build up positive ordinary worldly karma, but for it to act as a cause for reaching enlightenment for the benefit of all.” If we don’t dedicate it, it just automatically contributes to improving samsara. So we have to very consciously save the positive force in the enlightenment folder in our internal computer, because the default setting of the internal computer is that it is saved in the samsara-improvement folder, if we can use that example. That is the default setting. If you don’t press the button to save where you want it to be, it automatically goes by default into the samsara folder.

This is the seven-part practice and it is very profound. It is not to be trivialized. And it is very helpful for starting not only this sutra-level guru practice, but if we are going to start a daily practice, this is the one that we start with – seven-part practice. Absolutely fundamental.

Now the meditation continues by reminding ourselves of the advantages of focusing on our spiritual teacher’s good qualities and the disadvantages of focusing on their faults – the benefits and the disadvantages. It’s not that we’re going to go to Hell, nothing like that. The advantages and disadvantages are a little bit lighter. The disadvantages of dwelling on the faults, dwelling on them, being fixated on them. Right? And this is emphasized so much in all the sutras, and so on, and tantras, that if we focus on the positive qualities, we gain inspiration from them. It is uplifting. It gives us some model to aim for. If we become fixated and stuck on their shortcomings, then just over and over again we are harping on it, and what does it do? It gets us upset, it gets us depressed, and we are complaining all the time. It gets us into a very negative state of mind, a very low state of mind. What is the point of doing that? It is not going to help us, not the slightest. It is just going to bring us down in spirit. So we don’t want to deny these shortcomings, but we don’t want to get stuck on it with bitterness and anger. No use. No help.

And focusing on the positive qualities that are actually there, not just the ones we exaggerate and project. This can actually inspire us, because they can be confirmed that the teacher actually has them. If we imagine they have qualities which they don’t and then we find out they don’t have them, then again we will get very discouraged. That’s why it is very important for the teacher to be honest about what are their good qualities, not pretend that they have those that they don’t have; and not to hide their shortcomings, pretend that they don’t have them. Be very honest, very open. Same thing with the teachings, as I was just saying. If it’s the Buddha’s words, you say it’s the Buddha’s words. If it is something that the teacher is adding themselves, you say that. There is nothing wrong with that as long as you are honest about where it’s coming from. And especially if we spend all our time speaking with the other students, complaining about how terrible the teacher is. What is that going to accomplish except get everybody depressed and angry?

So we have about ten minutes left and maybe it might be nice if you have any questions to have that in the last minutes of this afternoon.

Question: What is the difference between the seven-part practice admitting when we have been misused by a teacher, and here when we are talking about the shortcomings of the teacher?

Alex: In the section about admitting the mistakes that we have made in the past, here we are particularly talking about with an abusive teacher. We may not be doing the guru-yoga with that abusive teacher, but bad experiences that we have had. Although we could think in terms of: “I have been abused by this teacher. What is the point of dwelling on that? The teacher did also have good qualities, and I did learn something from the teacher, so I can appreciate that.” That is possible, but more common is: “I have had this bad experience. Okay, I don’t want it to infect now the relation that I have with a better-qualified teacher.” And the point that we are doing now is thinking of the advantages of focusing on the good qualities and the disadvantages of focusing only on negative qualities. So it is a different point.

The teacher with whom we have had bad experiences – it is also important not to just say, you know, everything was bad, so I was just completely stupid; getting involved with such a teacher was a waste of time, because undoubtedly there was some positive things that we learned from that experience, from that relationship, even if it was just Dharma information. So it says very clearly in the teachings that if the relationship with the teacher was entered prematurely and unwisely, we keep a distance. Don’t just think negatively, but appreciate, “Okay, I learned some positive things and now I can’t really continue, but thank you very much.”

Question: Why is this relationship between a student and a teacher so central in Tibetan Buddhism, because it is much more so than in any tradition in the West, for instance. Of course, particularly in Tibet, it was difficult because there was no public school system. If you wanted to acquire knowledge, you had to seek the direct contact with a teacher. And you can get more energy from this direct contact. But why is it that in a world where we now have such good access to information, why is it still so important? Why is this still stressed so much?

Alex: Well, first of all, this emphasis on the student-teacher relationship is found not only in Tibet, but also in India and in China as well – in terms of proper relationships between people and so on. And I think that it is even more relevant nowadays in the West than it might have been a little while ago. If you look at the phenomenon of the Internet, computers, the chat rooms, cellphones – all these sort of things – people are getting more and more distant from each other. We might think that it is making them closer to each other, but it is not really, because it is just the opposite. You can give a false name in a chat room. You can assume any identity. You can shut off the computer if you don’t want to communicate anymore. You could not answer your cellphone if you don’t want to answer. I think that often people are getting more and more alienated from each other and more into their own worlds with their little machines and dependent on their machines. Particularly in the context of Mahayana, in which we want to be able to actually benefit others, it is very, very important to have human to human contact, real emotional contact with each other. With the spiritual teacher, although we might not have terribly much contact with the teacher, still, it is a living relationship in which there is an actual interchange on a real level. You can’t run away. You have to deal with the teacher and with the situation. So I find it very important for the development of our own personality and for the development of our own ability to deal with people and help them, which is what we are aiming to be able to do as a Buddha.

Question: Nevertheless, would it be right to say that the aim is to overcome this reliance on an external teacher and be guided entirely by an internal teacher or master?

Alex: I think we need to understand what that might mean. It is through relating to an external teacher, not instead of. But through relating to an external teacher, we can learn to rely on the internal teacher. The internal teacher isn’t some creature inside us or somebody sending us messages by telepathy. The internal teacher is our Buddha-nature, our potentials of the clear light mind. So the external teacher and the relation with the external teacher helps us to do that. Also, with the external teacher, we have an opportunity to build up a tremendous amount of positive force, in terms of not just learning from such a person, but helping them to help others. And a living model is so important, otherwise we just have some imaginary idea of what we are aiming for and that could be quite false.

We might not have the ability to help hundreds of thousands of people and so on. But if they hold these big events where His Holiness the Dalai Lama or other great teachers come and they teach so many people, and we help out even in a very mundane physical way by being a volunteer at one of these teachings, we participate, then there is an enormous amount of positive force. We would never be able to have such an opportunity just sitting by ourselves in front of our computer in our room.

Question: The question is about the inner guru. How do we understand that in terms of helping to give us more discriminating awareness, or the ordinary worldly powers, or what actually is this inner guru?

Alex: Remember the main function of the spiritual teacher is not to just simply give us information. That we can get from the Internet or a book, but to inspire us. Of course there are many other functions: to give the oral transmissions connected with lineage, answer questions, correct us, and so on. But the deepest thing is the inspiration, the strength on the path. This ultimately we have to derive from ourselves, from the clear light mind. The inner guru is the clear light mind, the subtlest level of mind, which is where all the Buddha-nature qualities and potentials are. This is what gives us our strength, our inspiration, to follow the various means and methods to actualize them. Just as we have to follow the various means to actualize the good qualities that we see in the teacher.

So I don’t think that we should take it so literally, that we’re going to get messages from our clear light mind, you know, like on our cell phone – there is a message that comes up, and there it is: “Now do this and now do that.” It is our source of strength; it is our source of inspiration. And through developing ourselves based on not only the inspiration from the teacher, but in resonance, in tandem with our own Buddha-nature qualities. As I said, we see the Buddha-nature in the teacher and it helps to activate the Buddha-nature within ourselves. Then we develop, on the basis of those qualities of the clear light mind, this discriminating awareness, this warmth, this ability to help others, and so on.