Maha Prajnaparamita Sastra Full By Nagarjuna

THE TREATISE ON THE GREAT VIRTUE OF WISDOM OF NAGARJUNA (MAHAPRAJNAPARAMITASASTRA) ETIENNE LAMOTTE

VOL. II CHAPTERS XVI-XXX

Composed by the Bodhisattva Nagarjuna and translated by the Tripitakadharmacarya Kumarajiva

Translated from the French By Gelongma Karma Migme Chodron

INTRODUCTION 490 SUPPLEMENT TO ABBREVIATIONS VOL.11 496 CHAPTER XVI: THE STORY OF SARIPUTRA 499 I. SARIPUTRA AT THE FESTIVAL OF GIRY AG RAM AS AJ A (p. 62 IF) 499 II. SARIPUTRA AND MAUDGALYAYANA AT SANJAYA (p. 623F) 500 III. CONVERSION OF SARIPUTRA AND MAUDGALYAYANA (630F) 505 IV. ORIGIN OF SARIPUTRA' S NAME (63 6F) 510 V. SARVAKARA (p. 640F) 513 VI. SARVADHARMA (p. 642F) 514 VII. WHY DOES SARIPUTRA QUESTION? (p. 646F) 517 CHAPTER XVII: THE VIRTUE OF GENEROSITY (p. 650F) 520 I. DEFINITIONS OF PRAJNAPARAMITA 520 II. THE METHOD OF NON-DWELLING (p. 656F) 525 CHAPTER XVIII: PRAISE OF THE VIRTUE OF GENEROSITY (p. 65HF) 526 CHAPTER XIX: THE CHARACTERISTICS OF GENEROSITY (p. 662F) 529 I. DEFINITION OF GENEROSITY 529 II. VARIOUS KINDS OF GENEROSITY 530 1. Gifts belonging to the three realms 530 2. Pure generosity and impure generosity 530 3. Other kinds of generosity 539 4. Inner generosity 548 CHAPTER XX: THE VIRTUE OF GENEROSITY AND GENEROSITY OF THE DHARMA (p. 692F) 552 I. GENEROSITY OF THE DHARMA 552 II. VIRTUE OF GENEROSITY 559 III. PERFECTION OF GENEROSITY 564 IV. NON-EXISTENCE OF THE THING GIVEN 574 NON-EXISTENCE OF THE OUTER OBJECT 575 1. Debate with the Realist 575 2. Debate with the Atomist 578 3. The object, subjective creation and emptiness 579 V. NON-EXISTENCE OF THE DONOR 581 NON-EXISTENCE OF THE ATMAN 582 1. The atman is not an object of consciousness 582 2. Debate with the Personalist 583 VI. GENEROSITY AND THE OTHER VIRTUES 593 1. Generosity and the virtue of generosity 593 2. Generosity and the virtue of morality 594 3. Generosity and the virtue of patience 596 4. Generosity and the virtue of exertion 596 5. Generosity and the virtue of meditation 601 6. Generosity and the virtue of wisdom 604 CHAPTER XXI: DISCIPLINE OR MORALITY (p. 770F) 607 I. DEFINITION OF DISCIPLINE 607 II. VARIOUS KINDS OF MORALITY 608 III. BENEFITS OF MORALITY 608 IV. DISADVANTAGES OF IMMORALITY 613 CHAPTER XXII: THE NATURE OF MORALITY(p. 782F) 615 FIRST PART: GENERAL MORALITY 616 I. Abstaining from murder 616 II. Abstaining from theft 624 III. Abstention from illicit love 627 IV. Abstention from falsehood 631 V. Abstention from liquor 640 SECOND PART: THE MORALITY OF PLEDGE (SAMADANASILA) 643

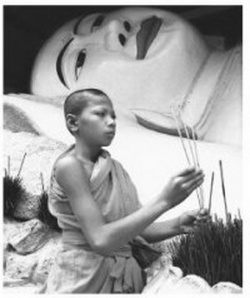

I. Morality of the lay person or avadatavasana 643 II. Morality of the monastic or pravrajita 658 CHAPTER XXIII: THE VIRTUE OF MORALITY (p. 853F) 668 CHAPTER XXIV: THE VIRTUE OF PATIENCE (p. 865F) 676 I. DEFINITION AND DIVISION OF PATIENCE 676 II. PATIENCE TOWARD BEINGS 677 1. Indifference toward sycophants 677 2. Indifference toward benefactors 686 3. Indifference toward women 687 4. Withstanding persecutors 694 CHAPTER XXV: PATIENCE TOWARD THE DHARMA (p. 902F) 703 I. GENERAL DEFINITION 703 II. ENDURING OUTER AND INNER SUFFERINGS AND THE AFFLICTIONS 704 [A. Enduring outer sufferings). - 704 [B. Enduring inner sufferings.] - 705 III. PATIENCE IN REGARD TO THE BUDDHADHARMA 710 CHAPTER XXVI: EXERTION (p. 927F) 721 I. EXERTION, FOURTH VIRTUE 721 II. THE BENEFITS OF EXERTION 725 III. PROGRESS IN EXERTION 727 CHAPTER XXVII: THE VIRTUE OF EXERTION (p. 946F) 736 I. THE NATURE OF EXERTION 736 II. THE VIRTUE OF EXERTION 737 III. EXERTION AND THE OTHER VIRTUES 750 IV. BODILY AND MENTAL EXERTION 751 CHAPTER XXVIII: THE VIRTUE OF MEDITATION (DHYANA) (p. 984F) 762 I. NECESSITY FOR MEDITATION 762 II. MEANS OF ACQUIRING MEDITATION 765 A. First Method: Eliminating the sensual desires 765 B. Second method: removing the obstacles 782 C. Third method: Practicing the five dharmas 791 III. DEFINITION OF THE VARIOUS DHYANAS AND SAVlAPATTIS 793 IV. QUESTIONS RELATING TO THE DHYANAS 802 V. DHYANAPARAMITA 809 CHAPTER XXIX: THE VIRTUE OF WISDOM (p. 1058F) 819 CHAPTER XXX: THE CHARACTERISTICS OF PRAJNA (p. 1066F) 827 I. 'GREAT' PRAJNA 827 II. PRAJNA AND THE PRAJNAS 827 1. Prajna of the sravakas 827 2. Prajna of the pratyekabuddhas 829 3. Prajna of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas 830 4. Prajnaof the_ heretics 830 III. THE PRAJNA AND THE TEACHING OF THE DHARMA 833 1. The teaching of the Pitaka 833 2. The Teaching of the Abhidharma 835 3. The teaching of emptiness 836 IV. UNDERSTANDING IDENTICAL AND MULTIPLE NATURES 848 1. Identical characteristics in every dharma 848 2. Multiple natures 852 3. Characteristics and emptiness of self nature 854 V. WAYS OF ACQUIRING PRAJNAPMARAMITA 856 1. By the successive practice of the five virtues 856 2. By practicing just one virtue 857 3. By abstaining from any practice 859

INTRODUCTION In Volume II, the reader will find an attempted translation of chapters XVI to XXX of the MahaprajnaparamitasaOtra. These fifteen chapters, which make up a consistent whole, comment at great length on a short paragraph of the Prajndpdramitadsutra (Pancavimsati, p. 17-18; Satasahasrika, p. 55-56), of which the following is a translation: "Then the Blessed One addressed the venerable Sariputra: 'O Sariputra, the Bodhisattva-mahasattva who wishes to know all dharmas in all their aspects completely should exert himself in the Prajnaparamita.' Then the venerable Sariputra asked the Blessed One: 'O Blessed One, how should the Bodhisattva- mahasattva who wishes to know all dharmas in all their aspects exert himself in the Prajnaparamita?' At these words, the Blessed One said to the venerable Sariputra:

'The Bodhisattva-mahasattva who abides in the Prajnaparamita by the method of non-abiding should fulfill the virtue of generosity by the method of refraining, by abstaining from distinguishing the thing given, the donor and the recipient; he should fulfill the virtue of morality by being based on the non-existence of evil deeds and their contrary; he should fulfill the virtue of patience by being based on non-agitation [of the mind); he should fulfill the virtue of exertion by being based on the non-slackening of physical and mental energy; he should fulfill the virtue of rapture by being based on the non-existence of distraction and rapture; he should fulfill the virtue of wisdom by being based on the non-existence of good and bad knowledges (variant: by not adhering to any system)."

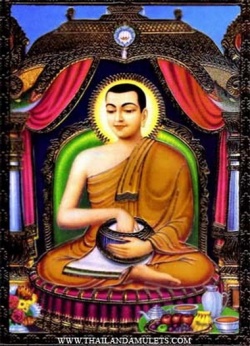

1 The main interlocutors of the Buddha in the Prajnaparamitasutra are Sariputra and Subhuti; chapter XVI of the Treatise is dedicated to their story: it contains a detailed biography of Sariputra and a short note on Subhuti (p. 634F). But it may seem strange that the Prajnaparamitasutra, which belongs to the literature of the Greater Vehicle, should be preached, not by the bodhisattvas affiliated with the Mahayana, but by sravakas, adepts of the Lesser Vehicle.

The reason for this is simple, as the Treatise explains (p. 636F): the bodhisattvas, called upon to dwell among beings whose conversion is their mission, have not entirely eliminated their passions and do not enjoy indisputable authority among men;

if they were responsible for teaching the Prajna, their word could be open to doubt. On the contrary, sravakas like Sariputra and Subhuti who have attained arhathood and destroyed every impurity (ksindsrava) are assured of an unequalled prestige and their testimony cannot be disputed: therefore it is to them that the Buddha entrusted the task of

1 Tatra khalu Bhagavdn dyusmantam Sariputram dmantrayam dsa: Sarvdkdram Sariputra sarvddharmdn i i i ii null E\ am ukta dyusmdn Sdriputro Bhagavantam etad avocat: i avail hodiiisatn \ i arvadhaniiaii abhisamboddluil ' ' van ayusi anputram etad avocat: Iha Sdripuitra bodhisattvena mahdsattvena prajndparainitayani stliitvastlianayogena ddnapdramitd parpurayitawap i ' i dhitdm updddya, silapdramitd paripurayituwa, i > inatdm updddya, \ it/ / natdm updddya, dhydnaparainita i i mirainita paripurayitarya prajuadauspi hit mi (\ in ml: sarvadharmdnahliiiiivesam) upadaya.

preaching the Prajna. Among all the sravakas, the Buddhas chose Sariputra and Subhuti who excelled over all the others, the first by the extent of his wisdom, the second by his acute vision of universal emptiness.

The religious ideal of the sravaka is the destruction of the passions, the arrival at arhathood and the attainment of nirvana; to this end, he practices the Noble Path in its threefold aspect: morality (Ma) which keeps him from any wrong-doing, concentration (samadhi) which purifies his mind, wisdom (prajna) by means of which he understands the general characteristics (sdmdnyalaksana) of dharmas, impermanence, suffering, emptiness and lack of self.

The practice of the virtues occupies only a subsidiary place in the career of the sravaka; his excellent qualities are, however, contaminated at the base by the essentially individualistic and egocentric character of his effort.

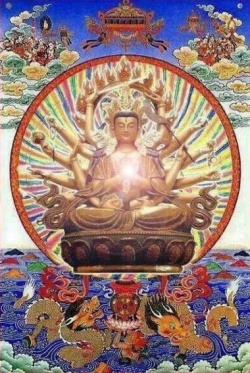

The religious ideal of the bodhisattva is quite different: renouncing entry into nirvana for the moment, he seeks to obtain the supreme and perfect enlightenment (anuttarasamyaksambodhi) which characterizes the Buddhas, to conquer the knowledge of all things in all their aspects (sarvadharmdndm sarvdkdrajndnam), knowledge that permits him to dedicate himself entirely to the benefit and welfare of all creatures.

In order to attain this omniscience, the bodhisattva must exert himself throughout his career in the six perfect virtues (pdramitd) which liken him to the Buddha. Among the heretics and sravakas, the practice of the natural virtues is marred by errors and egotism; among the bodhisattvas, on the other hand, the practice of the virtues attains perfection because it is disinterested and based on Prajnaparamita. Chapter XVII explains what this Prajnaparamita means and how to use it.

The Prajnaparamita is not an entity of metaphysical order, an absolute existent to which one could become attached; rather, it is a state of mind, a mental turning of mind which assures a radical neutrality to the person who adopts it. Transcending the categories of existence and non-existence, lacking any characteristic, the Prajnaparamita can be neither affirmed nor denied: it is faultless excellence.

bodhisattva adheres to it by not grasping it or, to use the time-honored expression, "he adheres to it by not adhering to it" (tistaty asthauayogeiia ). Confident in this point of view which is equally distant from affirmation and negation, he suspends judgment on everything and says nothing whatsoever.

Practiced in this spirit, the virtues which, among the religious heretics and sravakas, are of ordinary and mundane (laukika) order, become supramundane perfections (lokottaraparamita) in the bodhisattva.

Besides, since the bodhisattva refuses to conceive of the said virtues and to establish distinctions amongst them, to practice one paramita is to practice them all; not to practice them is also to practice them.

However, as the bodhisattva resides of choice in the world where he daily rubs shoulders with beings intoxicated by the three poisons of passion, hatred and ignorance, it is important to explain to people what distinguishes the paramitas from the profane virtues.

This is the subject of chapters XVIII to XXX. Chapter XVIII-XX. - Generosity (dana), for which great rewards are promised, consists of giving, in a spirit of faith, a material object or a spiritual advice to 'a field of merit', i.e., to a beneficiary worthy of receiving it.

The paramita of generosity makes no distinction between donor, recipient and gift because, from the point of view of the Prajna, there is no person to give or to receive, there is nothing that is given. To understand that is "to give everything at all times and in every way."

Chapters XXI-XXIII. - Morality (sila) makes one avoid the wrong-doings of body and speech that are capable of harming others.

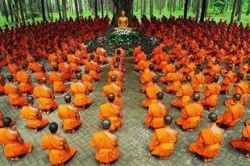

Apart from the general morality making up the rules of innate honesty essential to everyone, it is appropriate to distinguish the morality of commitment by means of which lay people and monastics of all classes solemnly undertake to follow a certain number of rules proper to their condition.

The paramita of morality singularly surpasses this restricted framework: is it based on the non-existence of wrong-doing and its opposite.

The sinner not existing, the sin does not exist either; in the absence of all sins, the prohibitions forbidding it have no meaning. The sinner does not incur our contempt; the saint has no right to our esteem. Chapters XXIV-XXV. - Although early Buddhism condemned anger, it did not attach great importance to patience (ksdnti). On the other hand, the bodhisattva raises it to the rank of paramita.

Nothing moves him, neither people nor things: he keeps a cool indifference towards the people who flatter him, the benefactors who cover him with their gifts, the women who seek to seduce him, the enemies who persecute him. He endures with equal facility the external sufferings caused by cold or heat, wind or rain, and the internal sufferings coming from old age, sickness and death.

It is the same insofar as his own passions are concerned: although he does not give himself up to them unreservedly, he avoids cutting them so as not to be hemmed in like an arhat in an egotistic complete quietude; whatever the case, his mind stays open to movements of great pity and great compassion.

But it is by means of dharmaksdnti that he attains the pinnacle of patience: he tirelessly investigates the Buddhadharma which teaches him not to adopt any definite philosophical position, which shows him universal emptiness but forbids him to conceptualize it. Chapter XXVI-XXVII. -

Throughout the entire Buddhist Path, the adept of the Lesser Vehicle displays a growing exertion (yiryci) in order to ensure himself the conquest of the 'good dharmas' or, if you wish, spiritual benefits.

But the bodhisattva is much less preoccupied with the paths of salvation; in his paramita of exertion, he ceaselessly travels the world of transmigration in order to bring help to beings plunged in the unfortunate destinies. As long as he has not assured the safety of an infinite number of unfortunate beings, he will never relax his bodily and mental exertion. Chapter XXVIII. -

For the purification of the mind, the sravaka had built up a discipline of rapture (dhydna), a grandiose but complicated monument of religious psychology in which India excelled.

The de-intoxication]] of the mind is a long-winded job: the candidate for sainthood must resolutely turn away from the five sense pleasures and triumph over the five faults which constitute an obstacle to concentrating the mind by means of an appropriate method.

Then he must ascend one after the other the nine successive absorptions (navdnupurvasamdpatti) which lead to the destruction of consciousness and sensation (samjndvedayltLinirodhii), a state which constitutes nirvana on earth.

In addition, a large number of secondary absorptions become grafted onto these main concentrations.

In the paramita of dhyana, the bodhisattva manifests a virtuosity much superior to that of the sravaka; he enters at will and whenever he wishes into the concentration of his choice, but his complete disinterestedness prevents him from enjoying its flavor.

The principal aim of his mental form of asceticism is to introduce ignorant and unfortunate beings to the purity of mystical states. Personally, he is disinterested because, from the point of view of the Prajna, distraction and concentration of the mind are equal; the sole motive that guides him is his great pity and great compassion for beings.

Chapter XXIX-XXX. - Religious heretics, sravakas and pratyekabuddhas all boast of possessing wisdom and they actually hold bits and pieces of it, but their wisdoms contradict one another and their partisans accuse one another of madness. If the wisdom of the sravakas and the pratyekabuddhas has an advantage over that of the heretics - the advantage of being free of false views - nevertheless it has the error of defining the general characteristics of dharmas and thus laying itself open to debate and criticism.

In his Prajnaparamita, the bodhisattva knows these wisdoms fully but adopts none of them; his own wisdom is the knowledge of the true nature of dharmas which is indestructible, unchangeable and uncreated. Seen from this angle, the dharmas are revealed as unborn (anutpanna), unceasing (aniruddha), like nirvana; or more precisely, they do not appear at all. Not seeing any dharma, the bodhisattva thinks nothing of them and says nothing of them.

Not recognizing any evidence, not adopting any system, he makes no distinction between truth and falsehood; he does not debate with anyone. The Buddha's teaching presents no obstacle, no difficulty, to the bodhisattva. And yet, what forms this teaching has taken over the course of time!

The Abhidharma sets out to define the dharmas and to specify their characteristics; the teaching on emptiness insists on the inconsistency of the atman and dharmas; the Pitaka defends a point of view sometimes realistic and sometimes nihilistic. Pursued into successive retrenchments, the sravaka no longer knows what to believe and goes from one contradiction to another.

Penetrating deeply into the threefold teaching of the Pitaka, the Abhidharma and emptiness, the bodhisattva, free of opinions (abhinivesa), knows that the Buddha's word never contradicts itself. Cognizing the identical and multiple characteristics of all dharmas, he confronts them with the emptiness of their self nature, but this very emptiness he refuses to consider. In order to acquire this Prajnaparamita, the bodhisattva is not bound to any practice.

The noble practice consists of practicing all the paramitas together or separately, provided that this is done with a detached mind; better yet, the noble practice is the absence of any practice, for to acquire the Prajnaparamita is to acquire nothing.

This brief summary far from exhausts the doctrinal and religious wealth contained in this second volume, but that would go beyond the framework of this introduction which merely summarizes it. It is sufficient to draw the reader's attention to several particularly interesting passages: the attempts to define the Prajnaparamita (p. 650-656F), a well-conducted refutation of the realist doctrine (p. 724-733F) and of the personalist doctrine (p. 734-750F), a comparison of the different prajnas of the sravaka, the pratyekabuddha, the bodhisattva and the heretics (p. 1066-1074F), a very thorough analysis of the threefold teaching of the Buddhadharma (p. 1074-1095F), a detailed description of the transmigratory world and, in particular, the Buddhist hells (p. 952-968F).

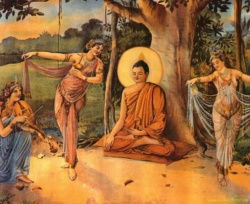

Although the Treatise comes under the literature of the Greater Vehicle, the reader will see all the major individuals of early Buddhism pass in front of him. In unedited detail, the Treatise tells the twofold assault against Sakyamuni by Mara and his daughters (p. 880-884F); 986-987F),

the return of the Buddha to Kapilavastu and the efforts of Yasodhara to win him back (p. 1001-1008F), the Devavatara and the culmination at Samkasya (p. 634-636F), the schism of Kausambl (p. 896-898F) and the various attempts perpetrated by Devadatta to supplant the Buddha and to take his life (p. 868-878F). The Treatise dedicates a whole chapter to the story of Sariputra and Maudgalyayana (p. 621-633F); it tells the slander of which these two great disciples were the victims on the part of Kokalika (p. 806-8 13F); it gives the reasons that determined Sariputra to renounce the Greater Vehicle (p. 701F). It narrates several episodes marking the life of the disciples and contemporaries of Sakyamuni; the temptation of Aniruddha by the goddesses of charming body

(p. 651-653F), the involuntary dance of Kasyapa (p. 654F, 1046-1047F), the ostentatious charity of Velama (p. 677-688F), the punishment of Devadatta and Udraka (p. 693-694F), Rahula's lies (p. 813-815F), the trickery of the nun Utpalavarna, the strange propaganda she carried out for the order of bhiksunis and her cruel death (p. 634F, 844-846F, 875F; the inquisitive and futile questions of Malunkyaputra (p. 913-915F0, the fabulous wealth of Mendaka and of king Mandhatar (p. 930-931F), the misadventures of the arhat Losaka-tisya (p. 931-932F), the laziness and frivolousness of the bhiksu Asvaka and Punarvasuka (p. 937F), the visit of king Bimbisara to the courtesan Amrapali (p. 990-992F), the cruelty of king Udayana towards the five hundred rsis (p. 993F), the punishment incurred by Udraka Ramaputra, immoderately attached to his absorption (p. 1050-1052F), the anxieties of the Sakya Mahanaman (p. 1082- 1083F), the humiliating defeat of the brahmacarin Vivadabala reduced to silence by the Buddha (p. 1084- 1090F), the entry into the religious life of the brahmacarin Mrgasiras (p. 1085-1088). By contrast, the present volume is strangely reticent on the lofty individuals of the Mahayana:

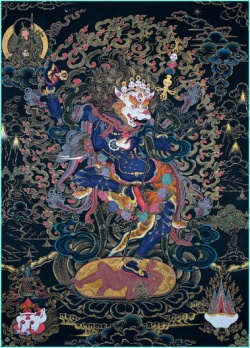

it mentions only in passing the name of the bodhisattvas Sarvasattvapriyadarsana (p. 75 IF), Manjusri (p. 754, 903F), Vajrapani (p. 882F), Vimalakirti (p. 902, 1044F), Dharmasthiti (p. 902F) and Maitreya (p. 930F); it is to the latter and to Manjusri that it attributes, without firmly believing it, the compilation of the Mahayanasutras (p. 940F).

The Treatise cites, at length or in extracts, about a hundred sutras of the Lesser Vehicle; the majority are borrowed from the Agama collections; when the Sanskrit version departs from the Pali version, it is always the former that is adopted; furthermore, the Treatise often refers to unknown Pali sutras, such as the Nandikasutra (p. 792-793F, 798F, 803F, 815-816F, 817-818F) and the sutra on Cosmogony (p. 835-837F). Several sutras are cited in the elaborated form which they have received in the post-canonical scriptures: this is notably the case for the Velamasutra (p. 677-688F) taken from a certain Avadanasutra, for the AsTvisopamasutra (p. 702-707F) taken from the Ta pan nie p'an king (see note, p. 705F), and for the Kosambaka (p. 896-898F), probably borrowed from the versified account in the Ta tchouang yen louen king

Although it abundantly cites the sutras of the Lesser Vehicle, the Treatise occasionally calls upon the ppMahayanasutras[[ of which it is the interpreter. We will note only a loan from the Saddharmapundarika (p. 752F), two quotations from the Vimalakfrtinirdesasutra (p. 902, 1044F) and a few vague references to the Pancavimsati (p. 1060F, 1091F, 1112F). However, the Treatise reproduces fully (p. 1060-1065F) the well- known Prajnaparamitastotra of Rahulabhadra, teacher or disciple of Nagarjuna. As P. Demieville has noted, the original Sanskrit of this stotra is reproduced at the head of many manuscripts of the Prajna. Otherwise, the author of the Treatise is by no means sectarian: he understands that many fragments of truth may be found outside works properly Buddhist; free of contradicting them, he does not hesitate to cite the Upanisads (p. 744F, 1073F) and other sutras of the heretics (p. 1073F). In the course of Volume I (see, for example, p. 104F, n. 1), we have noted that the Treatise uses the Sarvastivadin and Mulasarvastivadin Vinayas in preference over all the others. The present volume has frequent recourse to the second; it borrows from it the essence of the teachings on Sariputra (p. 621-633F), Devadarta (p. 868-878F) and Yasodhara (p. 1001-1012F). On the other hand, the author of the Treatise undoubtedly has never had the Pali Vinaya in his own hands.

This volume also contains a good sixty jatakas, avadanas, fables and apologues. The author has drawn heavily from collections such as the Kalpanamanditika, the Asokavadana, the Vibhasa, the Tsa p'i yu king, the Tchong king, etc. Although most of these stories are already familiar to us from the works of Chavannes, the version of the Treatise claims the reader's attention by means of important variants.

Among the tales which, under various titles, are most interesting, we may mention the story of the painter of Puskaravati (p. 672-675F), the Velamavadana (p. 678-688F), the Tittiryitam brahmacariyam (p. 718-721F), the successive lives of Mahatyagavat (p. 755-762F), the Utpalavarnajataka (p. 844-846F), the jataka of the flayed Naga (p. 853-855F), the ruse of the Kasmir arhat (p. 879F) and the story of the impostor brahmcarin confounded by the bodhisattva (p. 980-98 IF).

To facilitate references, the pagination of Volume I has been continued here. The division into chapters adopted by Kumarajiva in his Chinese translation has been retained despite their arbitrary nature.

To keep track of the content of the chapters, the reader is advised to refer to the table of contents.

The present volume has been greatly benefited by help and support which, as a result of circumstances, was cruelly missing from the previous volume.

New tools of research have been used; the list may be found in the supplement to the abbreviations. P. Demieville has been kind enough to review several passages that gave me difficulty and has given me precious references; my colleagues, Professor

A. Monin and J. Mogenet, have corrected the proofs; the Fondation Universitaire of Belgium has generously continued its financial support. To all my devoted friends I give my deepest thanks.

Louvain, 25 January, 1949.

SUPPLEMENT TO ABBREVIATIONS VOL. II AKANUMA = C. AKANUMA, Dictionnaire des noms propres du bouddhisme indien, Nagoya, 1931. Ancient India = Ancient India, Bulletin of the Archaeological Survey of India. Calcutta, from 1946. Arthaviniscaya = Arthaviniscaya, ed. A. FERRARI (Atti d. Reale Accademia d'ltalia, Vol. IV, fasc. 13, p. 535-625), Roma, 1944. BACOT, Documents de Touen-Houang = J. BACOT, F. W. THOMAS, C. TOUSSAINT, Documents de Touen-Houang relatifs a I'Histoire du Tibet (AMG, T. LI), Paris, 1940-46. BARUA, Barhut = B. BARUA, Barhut, 2 vol. (Fine Art Series No 1-2), Calcutta, 1934. BARUA, Gayd = B. BARUA, Gayd and Buddha-Gayd (Indian History Series, no. 1), Calcutta, 1934. Bhiksunikarmavacana = A fragment of the Sanskrit Vinaya (Bhiksunikarma-Vacana) ed. by C. M. RIDDING and L. de LA VALLEE POUSSIN, BSOS, I, 1920, p. 123-143. CODRINGTON, Hist, of Ceylon = H. W. CODRINGTON, A Short History of Ceylon, rev. ed., London, 1947. COEDES, Etats hindouises = G. COEDES, Histoire ancienne des Etats hindouises dExtrlme-Orient, Hanoi, 1944. [See id., Les Etats hindouises d'lndochine el d'lndonesie (Histoire du Monde, T. VIII 2), Paris, 1948]. CUMMING, India's Past = Revealing India's Past. A Co-operative Record of Archaeological Conservation and Exploration in India ami Beyond, ed. By Sir J. CUMMING, London. 1939. Dasakus. = Dasakusalakarmapathah, in S. Levi, Autour d'Asvaghosa, JA, Oct.-Dec. 1929, p. 268-871. Dharmasamuccaya = Dluuinasamuecaya, Compendium de la Loi, ed. by LIN LI-KOUANG (Publ. du Musee Guimet, T. LIII), Paris, 1946. DUTT, Mon. Buddhism = N. DUTT, Early Monastic Buddhism, 2 vol. (Calcutta Or. Series, no. 30), Calcutta. 1941-45. ELIADE, Techniques du Yoga = M. ELIADE, Techniques du Yoga, Paris, 1948. FATONE, Budismo Nihilista = V. FATONE, El Budismo « Nihilista» (Biblioteca Humanidades, T. XXVIII), La Plata, 1941. FILLIOZAT, Magie et Medecine = J. FILLIOZAT, Magie et Medecine (Mythes et Religions), Paris, 1943.

FILLIOZAT, Textes kouteheens = J. FILLIOZAT. Fragments de textes kouteheens de Medecine et de Magie, Paris, 1948.

FOUCHER, La route de I'lnde = A. FOUCHER, La vieille route de I'lnde de Bactres a Taxila, 2 vol. (Mem. de la Delegation arch, franc, en Afghanistan, T. I), Paris, 1942-47. FRENCH, Artpala = J. C. FRENCH, The Art of the Pal Empire of Bengal, Oxford, 1928. GHIRSHMAN, Begram = E. GHIRSHMAN, Begram. Recherches archeologiques et historiques sur les Kouchans (Mem. d. 1. Delegation arch, franc, en Afghanistan, T. XII), Cairo, 1946. Gilgit Manuscripts = Gilgit Manuscripts ed. by N. DUTT, vol. I, II, III (part 2 and 3), Srinagar, 1939-43. GLASENAPP, Indische Welt = H. v. GLASENAPP, Die indische Welt, Baden-Baden, 1948. GLASENAPP, Weisheit d. Buddha = H. v. GLASENAPP, Die Weisheit des Buddha, Baden-Baden, 1946. HOFINGER, Concile de Vaisali, = M. HOFINGEB, Etude sur le concile de Vaisali (BM, du Museon, vol. 20), Louvain, 1946. India Antiqua = India Antiqua. A volume of Oriental Studies presented to J. PH. VOGEL, Leyden, 1947. JENNINGS, Vedantic Buddhism = J. G. JENNINGS, The Vedantic Buddhism of the Buddha, London, 1947. KONOW, CII II = Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. II, part. 1, ed. By STEN KONOW, Calcutta, 1929. Kosakarika = The text of the Abitlluirmakosaktirikti of lasuhandhu, ed. By V. V. GOKHALE. Reprint from the Journ. of the Bombay Branch, RAS, N. S., vol. 22, 1946, p. 73-102. [edition of the manuscript of the Abhidharma- kosakarika discovered in 1935 in the Tibetan monastery of Ngor by RAHULA SAMKRTYAYANA] . KROM, Life of Buddha = N. J. KROM, The Life of Buddha on the Stupa ofBarabudur, The Hague, 1926. LAW, India in Early Texts = B. ('. LAW, India as described in Early lexis of Buddhism and Jainism, London, 1941. LAW, Magadhas = B. C. LAW, The Magadhas in Ancient India (RAS Monographs, Vol. XXIV), London, 1946. LAW, Panchalas = B. C. LAW, Panchalas and their Capital Ahichchatra (MASI, no. 67), Delhi, 1942. LAW, Rajagrha = B. C. LAW, Rajagriha in Ancient Literature (MASI, No 58), Delhi, 1938. LAW, Sravasu = B. C. LAW, Sravastiin Indian Literature (MASI, No 50), Delhi, 1935. LONGHURST, Ndgdrjunakonda = A. H. LONGHURST, The Buddhist Antiquities of Nagarfi (MASI, no. 54), Delhi, 1938.

MAJUMDAR, Advanced Hist, of India = R. C. MAJUMDAR, H. C. RAYCHAUDHURI, K. DATTA, Advanced History of India, London, 1946. MAJUMDAR, Guide to Sarnath = B. MAJUMDAR, A Guide to Sarnath, Delhi, 1937. MARSHALL, Guide to Sanchi = Sir J. MARSHALL, A Guide to Sanchi, sec. ed., Delhi, 1936. MARSHALL, Guide to Taxila = Sir J. MARSHALL, A Guide to Taxila, 3th ed., Delhi, 1936. MARHALL-FOUCHER, Mon. of Sanchi = Sir J. MARSHALL, A. FOUCHER, Monuments of Sanchi, 3 vol., Delhi, no date (1938?). MASC = Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon, Colombo, from 1924. MENDIS, Early Hist, of Ceylon = G. C. MENDIS, The Early History of Ceylon, 7th ed., Calcutta, 1946. Oriental Art- Oriental Art, London, from 1948. P. P. hrdaya = E. CONZE, Text, Sources and Bibliography of the Prajhaparamitdhrdaya., JRAS, 1948, p. 38-51. P. P. pindartha = G. TUCCI. Minor Sanskrit Texts on the Prajhaparamita. ). Prajnapciramitci-pindcirtha, JRAS, 1947, p. 53-75. Paramitasamasa = A. FERRARI, II Compendia delle Perfezioni di Aryasura (Annali Lateranensi, vol. X), Citta del Vaticano, 1946. RAMACHANDRAN, Sculptures from Goli = T. N. RAMACHANDRAN, Buddhist Sculptures from a Stupa near Goli I Wage, Guntur District (Bull, of the Madras Govern. Museum, vol. I), Madras, 1929. RAY, Maury a and Suhga Art = N. R. RAY, Maury a and Suhga Art, Calcutta, 1945. SASTRI, Ndlanda = H SASTRI, Nalanda and its Epigraphic Material (MASI, no. 66), Delhi. 1942. SIVARAMAMURTI, AmaravatT = C. SIVARAMAMURTI, Amaravati Sculptures in the Madras Government Museum (Bull, of the Madras Govern. Museum, vol. IV), Madras, 1942. Suvarnaprabhasa tib. = Suvarnaprabhasottamasutra, Die tibetischen Ubersetzungen hrsg. von J. NOBEL, Leiden-Stuttgart, 1944. TAKAKUSU, Buddhist Philosophy = J. TAKAKUSU, The Essentials of Buddhist Philosophy, Honolulu, 1947. THOMAS, Tib. lit. Texts = F. W. THOMAS, Tibetan literary Texts and Documents concerning Chinese Turkestan, Part I (Or. transl. Fund, vol. XXXII), London, 1935. Traite, I = Vol. I of the present work. VOGEL, Buddh. Art = J. PH. VOGEL, Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon and Java, Oxford, 1936, WALDSCHM1DT, Lebensende des B. = E. WALDSCHMIDT, Die Uberlieferung vom Lebensende des Buddha, 2 Teile (Abhandl. d. Akad. d. Wissens. in Gottingen, Dritte Folge, no. 30), Gottingen, 1944-48. WINSTEDT, Indian Art = SIR B. WINSTEDT, Indian Art. Essays by H. G. Rawlinson, K de B. Codrington, J. V. S. Wilkinson and John Irwin, London, 1947.

CHAPTER XVI: THE STORY OF SARIPUTRA

Sutra: The Buddha said lo Sariputra (Tatra klicilu Bhagavan ayiisinanatain Saripiitram cinum travel m asa). Sastra: Question. - The Prajnaparamita is the system (dharma) of the bodhisattva-mahasattvas. Why does the Buddha address himself here to Sariputra and not to the bodhisattvas? Answer. - Of all the disciples of the Buddha, Sariputra is by far the foremost in wisdom (prajna 1 ). A stanza of the Buddha says: "Except for the Buddha Bhagavat, the knowledge (jnana) of all beings would not equal a sixteenth part compared with the wisdom (prajna) and learning {bahusruta) of Sariputra," 3

I. SARIPUTRA AT THE FESTIVAL OF GIRYAGRAMASAJA ( P 621F)

Furthermore, by his wisdom (prajna) and his learning (bahusruta), Sariputra possessed great qualities (guna). In his youth, at the age of eight, he recited the eighteen kinds of sacred books and understood the meaning of all the treatises. At that time, there were two nay i ! inu (/ d>. a ja) n \lo k'ie t'o (Magadha): the first was called Ki li (Giri) and the second A k'ie lo (Agra). 5 They brought the rain at the proper time and the country did not experience the years of famine. The people were grateful to them and regularly, in the [second] month of spring (caitra), they went in a crowd to the nagas to hold a great festival (mahasamdja): they played music (yadyd) and palavered the whole day. From early times up until today,

Cf. Anguttara, I, p. 23 (= Tseng yi a han, T 125, k. 3, p. 557b): eta ihikklun una savakdnam bhikkhunamma,' , u \ hdam Sdriputto. 3 Cf. Divyavadana, p. 394: Sarvalokasya yd prajna sthapayitvd Tathdgatam, Sariputrasya prajfiaya kalani uarhati sodasun. 4 In this paragraph, the Mpps regards Sariputra as a child prodigy; but according to other sources, Sariputra was much older when he was present at the Giryagrasamaja; moreover, he was accompanied by his friend Ylaudgalyayana (ICoIita). During this festival, Ihc two friends exchanged disenchanted thoughts on the worlhlcssncss of human pleasures and decided with one mind to leave the world and embrace the religious life: cf. Mahavastu, 111. p. 57-59; Dhammapadattha, I, p. 89-90 (tr. Burlingame, Buddhist Legends, I, p. 198-199; Fo pen hing tai king, T 190, k. 48, p. 874a-c (tr. Beal, Romantic Legend, p. 325-327); Mulasarv. Vinaya in T 1444, k. 1, p. 1024 a-b, and Rockhill, ii/e, p. 44-45. 5 Misled by the Fan fan yu, T 2130, k. 7, p. 1030b, Akanuma (p. 321a, 7b) restores Ki li as Krimi and A k'ie lo as Agala. But it clearly concerns (he nagas Giri and Agra whose conversion and adventures arc told in Ken pen chouo... yao che, T 1448, k. 4, p. 17a seq. In this translation Yi tsing renders Giri as Chan (46) "Mountain", and Agra as Miao (38 and 6) "Admirable".

this assembly was never missed and to this reunion was given the same name as that of the nagas [namely, giryagrasaindja']. On that day, it was customary to set up four high seat:; (brsi), the first for the king, the second for the crown prince (kumara), the third for the prime minister (mahdmdtya) and the fourth for the scholar (yddin). One day, Sariputra, who was eight years of age, asked the crowd for whom were the high seats set up. They answered that they were for the king, the crown prince, the prime minister and the scholar. Then Sariputra reviewed (pariksate) the people of his time [and saw] that, among the brahmins, etc., nobody surpassed him in intelligence (abhijnd), charm (prasdda) and beauty of appearance; he therefore mounted the seat of the scholar and sat there cross-legged (paryankam baddhvd). The people were astounded; some said: "He is a young fool who does not know anything"; others said: "The measure of his wisdom surpasses that of men". While admiring his bravery, everyone felt uneasy and, out of regard for his young age, abstained from debating with him. Then they sent their young students to engage him in conversation and question him: Sariputra' s answers were perfect and his arguments conclusive, The scholars cried out at this wonder (adbhuta): "Fools [136b] and wise men, great and small, he confounds (abhibhavati) them all." The king quite happily conferred on him a command, the revenue of a village {grdmd) which was ceded to him in perpetuity. The king, mounted on an elephant, rang a bell (ghanta) and proclaimed [the news] everywhere; and in the six great cities of the sixteen great countries (janapada), there was nobody who did not congratulate him. II. SARIPUTRA AND MAUDGALYAYANA AT SANJAYA 8 (p. 623F) 6 According to this cxplan in >n < lip i <\ . 1111 1 1 ivould mean Festival in honor of the Nagas Giri and Agra: again, a false etymology has given rise to a myth. In reality, Giryagrasamaja (giriyagrasamaja in Mahavastu, III, p. 57; / in Avadanasataka, 11, p. 24: gii in in. II, p. 107, 150; IV, p. 85, 267; Jataka, III, p. 538; Dhammapadattha, I, p. 89) means simply a festival reunion on the summit of the mountain. Buddhaghosa was not deceived by it and ht< iK > , I " i < < > ti girimi < i < iamajjo. On the nature of this festival, see E. Hardy in Album Kern, p. 61-66. It was a great seasonal festival (Ta tsie houei) celebrated at Rajagrha and in turn (T 1444, k. 1, p. 1024al9) on each of the five great mountains surrounding the city (T 190, k. 48, p. 874a). The Mpps tells us that it lasted the entire day and took place 'in the second month of spring", i.e., the month of Caitra; this indication allows us to correct the reading of the Avadanasataka, II, p. 24, girivalgusamdgt U i mlgama "leunion [of the month] of Phalguna on the mountain". Like all reunions (sainaja) of this kind, the festival included spectacles, songs, dancing and music (Mahavastu, III, p. 57; Avadanasataka, II, p. 24-25; DIgha, III, p. 183); special seats were reserved for individuals (T 1444, k. 1, p. 1024a). 7 This is probably the natal village of Sariputra, situated a half-yojana from Rajagrha: it was called Nala or Nalanda (Mahavastu, III, p. 56, 1. 6; Fo pen hing tai king, T 190, k. 47, p. 273c; Ken pen chouo... tch'oukia che, T 1444, k. 1, p. 1022b; Fa hien, tr. Legge, p. 81); Kalapinaka (Si yu ki, T 2087, k. 9, p. 924cl4), or also Upatissa (Dhammapadattha, I, p. 99). 8 The conversion of Sariputra (= Upatisya and Maudgalyayana (= Kolita) is well-known in Buddhism; in search of the Immortal, the two friends began first at the school of Sanjaya who was not slow in making them his disciples; one day on th tskirts of Rajagrh riputra met the bhil * jit (= Upascna) vvh hi lin i one tanza, the Buddhist credo: ye dhani a ictt pn >lia ah 'incited to this new faith, Sanputia went immediately to find his

friend Maudgalyayana and they both went to the Buddha who preached his Dharma to them and conferred ordination on them. - This laic has been the object of a twofold tradition: In the old tradition, Saiijay a is presented in an unfavorable light, as an obstinate heretic; in the more recent tradition, to which the Mpps adheres, Sanjaya appears as a precursor of the Buddha. I. Old Tradition. - Pali sources: Vinaya, I, p. 39-44 (tr. Oldenberg, I, p. 144-151); Apadana, I, p. 24-25; Jataka, I, p. 85; Dhammapadattha, I, p. 90-95 (tr. Burlingame, Legends, I, p. 199-202); Suttanipata Comm.

I, p. 326 scq. Sanskrit sources: .Ylahavastu, III. p. 59-65. Chinese sources: Wen fen liu, T 1421, k. 16, p. HOb-c; Sseu fen liuT 1428, k. 33, p. 798c-799b; P'ou yao king, T 186, k. 8, p. 533c; Ta tchouang yen king, T 187, k. 12, p. 613c; Yin kouo king, T 189, k. 4, p. 652a; Fo pen hing tai king, T 190, k. 48, p. 875a seq. (tr. Beal, Romantic Legend, p. 27-331); Fo so hing tsan, T 192, k. 4, p. 33b (tr. I I li In h 'ii '/ h i. in la Orientalia W, 1937, p. 21-23); Fo pen hing king, T 193, k. 4, p. 81b; Tchong pen k'i king, T 196, k. 1, p. 153b; Ta tai king, T 397, k. 19, p. 129a; Si yu ki, T 2087, k. 9, p. 924c- 925a (tr. Beal, II, p. 177-179). According to various sources, Sanjaya, Sariputra's and Maudgalyayana's preceptor, is none other than SanjayT Vairahputra (.Ylahavastu, III, p. 59, 1. 9), Sanjaya Belaniiiputta in Pali, one of the six well-known heretic masters. The agnostic doctrines which he professed (cf. DIgha, I, p. 58) connect him closely with the Amaravikkhepika, crafty sophists who, in debate, 'thrash about like eels' (DIgha, I, p. 27).

Sariputra and Maudgalyayana soon surpassed their teacher and the latter entrusted some of his disciples to them (Dhammpadattha, I, p. 90). Informed about the Buddha by As\ i|i \ nil I il ina decided 1 i I he new faith and invited their former teacher to follow Ihcm: bul Sanjaya tried to hold them back (Vin. I, p. 42; Mahavastu, III, p. 63; Fo pen hing tsi king, T 190, k. 49, p. 877b), or at least refused to accompany them on the pretexl that a teacher such as he could no longer learn from anyone else (Dhammapadattha, I, p. 94).

Finding himself abandoned by Sariputra, MniJ I yana nJ u limn'i' d niln i |i ipl iijaya b n ick "hot blood spmted foith from his mouth" i ihitan t i I i J i i| mini liiil I ) Hi i pen hill i king (I 190. k. 48. p. 877b) adds thai this spitting of blood cost him his life; but according to she Dhammapadattha, I, p. 95, he recovered and those of the disciples who had abandoned him returned. Subsequently, he engaged in debate with the Buddha (DTvyavadana, p. 145). II.

More Recent tradition. It is represented by several late texts, such as the Mpps (k. II, p. 136b-c; k. 40, p. 350a; k. 42, p. 368b), the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya (T 1444, k. 2, p. 1026a-c; Rockhill, Life, p. 44-45) and also perhaps the Tch'ou fen chouo king, T 498, k. 2, p. 768a-b. Sanjaya, the teacher of S. and .VI. , has nothing in common with the heretic of the same name. He did not belong to the clan of the Vairati, but to a wealthy family of the Kaundinya (cf. T 1444, k. 2, p. 1026b); far from professing agnostic views, he prepared the paths for Buddhism by preaching the ldigious lite, non-h i min i I, celibacy (h i md nin u i ii l\ ill Saii]aya is cared for with great devotion by S. and M.; in front of them, he maintains that he has found the Path, but he announces to them the birth of the Buddha at ICapilavastu. recommends thai they join him and enter his order. S. and M. conduct a spl ndid funeral foi i | i i 111 i I him laving di i 1 1 1 I J 'i ma but of having held it back for himself.

It is then that they take an oath to communicate to each other the seeiei of the Immortal as soon as they have discovered it. It is long after the death of Sanjaya that S. will meet Asvajit, who introduced the two friends to the Buddha. In summary, in this new tradition. Sanjaya appears as the Buddha's precursor, and we may wonder if the theme of precursor, foreign to early Buddhist hagiography. was not introduced at Kapisa Gandhara mid in Kasmir by

s of the Greco -Hadrians. Saka Pahlava and Yue-tche, with other stories - miracles or parables - which were current at the beginning of our era among circles devoted to oriental gnosis. For this subject, sec the significant writing of Fouchcr, Art grcco-houddhique, II. p. 561 -566. i .1 11 i I'ii ii n I ilion ol thi p i n ol tin vhil isar\ \ m i i itin ; to •> ni| iva. It i imilai in all details to the story of the Mpps.

Ken pen chouo... tch'ou kia che, T 1444, k. 2, p. 1026 a-c: At that time there w as a teacher called Chan che yi (Safijaya). Upatisya (= iri] rb i nil oli I (= <A ud l\ i ina) went to him and asked: "Where is the master resting?" They were told: "The master is in his room." Hearing this, they had this thought: "Wc have been here for a long time; we have not heard that he is resting." Then Kolita [and his companion] thought again: "This man is resting; we should not wake him suddenly; lei us wail near his bed and then we will see him." Having said that, they hid behind a screen.

Then Safijaya woke from his sleep and his senses were calmed {viprasanendriya). The two friends, seeing hi i i ipproach J aid I n Ji ou havi In I 'I inn ye (d/itn c )'? Vvh I doctrine do you profess? What u oiu benefits (v/.vi i ' h it i il mi >i di> t {Iva I on practice? What fruition (phala) have you received?" He answered: "This is what I see and this is what I say: Avoid falsehood (mrsavada): do no harm to beings {sattvesv avihimsd); do not be born (anutpddd), do not die (amarana), do not fall (apatana) and do not disappear (anirodhd); be reborn among the two [classes] of Brahmadevas." The two friends asked him the meaning of these words.

He answered: "To avoid falsehood is the religious iile (pravrajya); lo do no harm is the root (inula) of all the dharmas; the place where there is neither birth nor death, neither falling nor disappearance, etc., is nirvana; to be reborn among the two [classes] of Brahmas is the brahmic conduct (hralunacarya) practiced by the brahmins: all seek this place." Ha\ ing heard these words, the two friends said to him: "O Venerable One, we would like to embrace this religious life and practice brahmic conduct."

They entered the religious lile under him and at once the news spread everywhere thai Kolita and [his friend) had entered into religion with Safijaya. One day, Safijaya, who possessed great wealth (lahha), had (his thought: "I used to belong to the Kiao tchou (Kaundinya) family and still today, as a member of this family, I have great wealth. I should not forget these two virtuous companions.

That would not be good on my part." Having thought thus, Safijaya, who had five hundred disciples under his direction, gave them to the two friends: each of them received two hundred and fifty pupils and they agreed to teach them the doctrine. Then Safijaya became sick. Upatisya said to Kolita: "The master is sick. Would you go and look for medicines or do you want U> erne for him?" Kolita answered: "You have wisdom (prajnd); you should care for him; I will go to find medicines." Kolita left to look for herbs, roots, stems, flowers, etc.; he gave them to his teacher who ate them. But the illness grew worse. One day, the master laughed softly. Upatisya said to him: "Great men cannot laugh v, ithout reason; but our teacher has just laughed; what is the reason?" The master replied: "It is just as you said: I need to laugh.

In Kin tcheou (SuvarnadvTpa), there was a king called Kin tchou (Suvarnapati); he died and was going to be cremated; his grieving widow threw herself into the fire. People arc fools (miidlia) and lei themselves be led by desire (kdma). This sickness of dcsn i ( nyadlii) in ih in < uffci Upati i 1 d him n ha n * hat month and what day this event had taken place. Safijaya specified the ycai . (he month, the da\ and the hour.

The two friends took note of this revelation. Again they asked their teacher: "We have left the world {pravrajUa) in order to cut transmigration (sainsara) and the master has welcomed us. We would like him to tell us if he has succeeded in cutting samsara." Safijaya answered: "When I left the world, it was for the same purpose as you; but I have obtained nothing. However, during the posada of the fifteenth, a group of devas in the sky (dkdsa) spoke the following prediction: In

At that time, the master of the oracles had a son whose name was Kiu liu t 'o (Kolita) and the name of the family was Ta mou k'ien lien (Mahamaudgalyayana). Sariputra was his friend. Sariputra was outstanding for his talents and his intelligence, Maudgalyayana for his fearlessness and vivacity. These two children were equal in talent and wisdom and also in qualities and conduct. [They were inseparable]: when they went out, it was together; when they returned, it was together.

When they were a little older, they made an agreement of eternal friendship. Then, both of them experiencing disgust for the world (lokasamvega), they left home (pravrajitd) to practice the Path (mdrga), became disciples of a brahmacarin and diligently sought entry into the Path (margadvara). For a long time this had no result. They questioned their teacher, Chan choye (Sanjaya) by name, who answered: "I myself have spent long years seeking the Path and I do the family of tin. ( / i ik; i i \ mi ; prim (kun has been 1 on l.i I In i> i< i il Mi I lim il i i < In i i i called I'cn Ion (Bhagirathi): on Ihc bank of this river Micro is the hermitage of the rsi Kia pi lo (ICapila).

Brahmins expert in divine signs and omens have predicted that the young prince would become a cakravartin king, but, if he leaves the world, he will become a I ith il ,ih il rmj iksambuddha lenowned foi his ten powers. You should enter into the rel i iou lifi in hi ird I ndpra ti i acarya there. Do not rely on the nobility of your family; practice brahmacarya; tame your senses. With him you will find the marvelous fruition and escape samsara." l-'ollowin Mil pi imbl th c ichci pol lln thai i mskril I d inn nil- J hakra uti,p 4; Nettip. P. 146;

Mahavastu, III, p. 152, 153; Divya, p. 27, 100, 486; JA, Jan-Mar. 1932, p. 29): Sarve ksaydnta nit yah , ktnatdh samucchrayah, i 'prayogat am nam hi jivitam "All that is compounded ends up in destruction: all elevations end up in falling; all unions end up in separation: life ends up in death." Shortly afterward, the teacher died and his disciples. Inning wrapped him with blue (inla), yellow (pita), red (lohita) and white (avadata) wrappings, carried, him into the forest where lhc\ proceeded, to cremate him. Oi d \ brahmin from i n Ivrpa i ncd i fa ( .m il l m I | ha and met U] i i The latter asked him where he came from and he responded that he came from SuvarnadvTpa. "Have you seen something wonderful there'?" asked Upatisya. The brahmin answered: "Nothing but this: when king SuvarnadvTpa died and was cremated, his mourning widow followed him to the pyre." Upatisya asked in what year, what month and what day [that had happened], and the brahmin replied: "It was such and such a year, such and such a month and such and such a day."

Upatisya then examined the secret [w hich Sanjaya had told him]: the words of the master were verified. Then Kolita said to Upatisya: "Our teacher had discovered the Holy Dharma but he held it secret and did not reveal it to us. If the teacher had not realized the divine eye (diryacaksus) and the divine car (divyasrota), he at least knew whal > i h ppenin in foreign r< nci I olita then lid to him 11 Upati li inl lligcnt (medhavin) and wise (prajhavat). He will have found the Hols Dharma with our teacher, but he has not communicated ii to me." Having had this thought, he said: "Let us take an oath that the first [of us] who finds the Holy Dharma will communicate it to the other." Having taken this oath, they left together.

At that time, the Bodhisattva was twenty- nine years old.... 9 Kolita is also the name of the village where he was born (Mahavastu, III, p. 56; Dhammapadattha, 1, p. 88): ii was located a half-yojana from Rajagrha. The leading Kolika is found in the l-'o pen hing iai king, T 190, k. 47, p. 874a5; and the Si yu ki, T 2087, k. 9, p. 924M7; Lin yuan "Forest garden" in the Ken pen chouo... tch'ou kia che, T 1444, k. l,p. 1023cl8.

not even know whether the fruit of the path (margaphala) exists or not. I am not the man you need; I have found nothing." One day their master fell ill.

Sariputra stood at his head and Maudgalyayana at his feet; the teacher gasped for breath and his life reached its end. Suddenly he smiled with pity. The two friends, with one accord, asked him why he smiled. The teacher replied: "The customs of the world (lokasamvrti) are blind and affected by the emotions (anunaya). I see that the king of Kin ti (Suvarnabhumi) has just died and his main wife has thrown herself on the funeral pyre to join him; but for these two spouses, the retribution for actions (karmavipdka) is different and the places where they will be reborn (janmasthana) will be different (visista)."

Then the two disciples put down their teacher's words in writing in order to verify their accuracy [later]. Some time later, when a merchant from Suvarnabhumi came to Magadha, the two friends questioned him discretely; the things their teacher had said had actually occurred. 10 They uttered a sigh of 10 If this story is correct, it proves that the practice of suttee, the w idow offering her life in the flames of the funeral pyre consuming lh< i up ofhcrhn mJ i cm nl in uvarnad tpa h I'i nine of the Buddha.

This is of interest because, in all the Vcdic literature and even in the siitras, this cruel practice is rarely mentioned, and the epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata mention it only exceptionally (cf. J. Jolh Ret lit in • Situ , p. 67-69). The oldest and most important evidence is that of the classical writers: Aristotle, contemporary of Alexander the Great, cited by Strabo, XV, 1, 63; Cicero, De nat. deorum, V, 77-78; Valerius Maximus, II, 6, 14.

The Mpps reproduces here almost word-for -word the story in the Mulasarvasth adin Vinaya (see below, p. 626F as note); but, while Kumarajiva, translator of the Mpps, locates the fact in Kin ti, "Land of Gold" (Suvarnabhumi), Yi tsing, translator of the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya. locates ii in Kin tchcou "Golden Island" (Suvarnadvlpa). As it is a matter of the same story, we must conclude - and this is suspected - that Suvarnabhumi is synonymous with Suvarnadvlpa. We know exactly what Yi tsing means by Suvarnadvlpa: in two passages of his Ta fang si yu k'ieou fa kao seng tchouan, T 2066, k. 2, p. lie, lines 5 and 7, lines 5 and 11, he identifies it as the land of Fo che (cf. Chavannes, Religieux eminents, p. 181 and 182; p. 186 and 187). But at the time of Yi tsing (635-713), the state of Fo che or Che Ufa che (SrTvijaya), as evidenced by the three inscriptions in old Malax dating from 683 to 685 and found at I'alcmbang, Djambi and Bangka, "extended its domination over I'alcmbang (Sumatra).

Bangka and the hinterland of Djambi, conquered Malayou (Djambi) about the same time and in 775 left evidence of its domination over the west coast of the Malay peninsula (Ligur)" (G. Coedes, A propos d'une nouvelle theorie sur le site de SrTvijaya, J. Mai. Br. R.A.S., XIV, 1936, pt. 3, p. 1-9; Etats hindouises, p. 102-105).

It must be left to the historians to explain why the Mulasarv. Vin. and the Mpps insist on establishing a connection between Sahjaya, the preceptor ofS. and M , and u irnad Ppa \ m y recall thai fi tsin mentioi thi pi en ifthi hit usastnada, in the 7th and 8th centuries, in the kingdoms of Sriksetra and SrTvijaya (cf. Coedes, Etats hindouises, p. 94, 105, 109), and that the name of Sanjaya was made famous in the 8th century by the founder of the Javanese dynasty in Mataram (Id., ibid, p. 109 seq.).

However that may be, the Hindu writers have left only a vague idea of the location of Suvarnabhumi (see R. C. Mammd u ' I ! ' Kangacharya i / Ivvpa Aiyangar Comm. Vol, p. 462-482). Gavampati, one of the heroes of the first council (cf. Treatise, I, p. 98-99F), before settling permanently in the \ imana o\ the Sinsa, w cut to the pratyaiitajanapwla or frontier countries, i.e., Suvarnabhumi, by the Buddha's order (Ken pen chouo... tsache, T 1451, k. 5, p. 228a), and to believe the ICarmavibhahga, p, 62, which claims that, in the Land of Gold, the saint Gavampati converted the population for a hundred leagues iji ii iii lually, according to the Burmese tradition: "King Thiri-.Ylatauka had been informed that, after the death of Gaudama, a Rahan named Gambawatti

relief and said: "Perhaps the master hid his secret because we were not worthy." The two friends exchanged the following oath: "The first to find the Immortal (amrta) must communicate its flavor (rasa) to his friend." 11

CONVERSION OF SARIPUTRA AND MAUDGALYAYANA

At that time the Buddha, having converted the Kasyapa brothers and their thousand disciples, was traveling about in various countries and came to the city of Rajagrha where he stayed at the Venuvana. The two brahmacarin masters (Sariputra and Maudgalyayana), hearing that a Buddha had appeared in the world, (Gavampati) had brought thirty-two teeth of the Buddha and placed them in a dzedi (caitya) on Mount Ind-Danou north-west of Thatum (in Pali, capital of Burma, between the mouths of the Siltang and the Saloucn)." (Bigandet, Gaudama, p. 371).

Even today, Gavampati, under iha name Gavompade, is one of the favorite saints of the Vlons and the Taking sof Burma (cf. Duroiselle, cited in Przyluski. Concile, p. 241). - After the third council at Pataliputra, Sona (the Prakrit word for gold) and Uttara went to Suvarnabhumi, rid the land of the pisacas and converted man\ | " pl< ihci (cl I >ip ini \ ill 12 VI a ha im \II, v. 6, 44 seq.; Samantapasadika, I, p. 64. - In the first century of our era, Pomponius Mela (III, 70, Pliny the Elder (VI, 55, 80); the Periple of the Erythrean Sea (§ 56, 60, 63) and losephus (Ant. Jud., VIII, 6, 4) were only vaguely aware of the Chryse Chersonesos.

Whereas Ihc Periple (>j 60) places at ICamara (IChabari of Ptolemy = ICavari-paUinam at the month of the Kaveri), at Podouke (Pondichery) and Sopatma, the three great ports, close to one another, from which the big ships called kolandia (kola in Buddhist Sanskrit texts) set sail for Chryse, Ptolemy (VII, 1, 5) locates further north, near Chicacole, the port of departure (aphtcrioii) of travelers destined for Ihc Golden Chersonesos. It is at Tamralipti (Tamluk at the mouths of the Ganges) that the Chinese pilgrims, fa hicn ai the beginning of the 5th century and Yi- tsing at the end of the 7th century embarked in Ihc return voyages from India to C hina. \\ ithout a doubt, it is also at Tamralipti that, at the time of the compilation of Ihc Jatakas. Ihc merchants [Samkha and Vlaha Janaka) left Benares or Campa, in the Ganges valley, took to sea destined for Suvarnabhumi, the land of gold (lataka, IV, p. 15; VI, p. 34). Finally it is certain thai (he meed ports of the western coast: Bharakaccha (Greek Barygaza, modern Broach), Surparaka (Souppara, Sopara) were connected with the Golden Chersonesos" G. Cocdes, Ltats liindoiiixeex,p. 35).

This is the case notably for the musician Sagga in his search for the beautiful Sussondi, who embarked at Barukaccha destined for Suvannabhumi (.lataka. 111, p. 188). Ihc merchants of (he .Ylahakarmavibhahga" went down to the great ocean, sailed for the Land of Gold and other countries, visited (he Archipelago and made their fortunes (p. 51: mahasamudram avatuya Suvarnahhuiniprahlirtiiii desaiitarani gtitva dvipaiitaraui ca pasyanti dravyopdrjanam ca kurvanti); or also "They visited the Land of Gold, the island of Ceylon, and the rest of the rchipclago" (] ii'in Siniliahuh i vanti).

But the voyage i dangerous: when the sailors have traveled seven hundred leagues in seven days", it is not rare that the ships take on water every vv here and sink in mid-ocean. 11 This covenant between the two friends is also noted in the other sources: cf. Vinaya, I, p. 39: yo pathamam ainatam adhigaccchati so arocetu: .Vlahavastu, 111, p ^ l > vo in J u sval n irmavinayan ... tena aparasya dkhydtavyam. 12 Cf. the parallel sources noted above, p. 623F, n.2

went to Rljagrha together to welcome the news. At this time, a bhiksu named A chouo che (Asvajit), 13 [one of the first five disciples), wearing his robes (civara) and carrying his begging bowl (patra), entered the city to beg for his food. Sariputra, noting his fine manner and his meditative faculties, came to him and asked:

"Whose disciple are you? Who is your teacher?" Asvajit answered: "The crown prince (kumara) of the Sakya clan, disgusted by the sufferings of old age {jam), sickness (vyddhi) and death (marana), has left the world (pravrajita), exerted himself on the Path and has attained complete perfect enlightenment (anuttarasamyaksambodhi). He is my teacher." Sariputra said: "Tell me what is your teacher's doctrine?"

He replied with this stanza: I am still young, My instruction in it is still at its beginning [136c] How could I speak truthfully And explain the mind of the Tathagata? Sariputra said to him: "Tell me its essence in summary (samksiptena)r Then the bhiksu Asvajit spoke this stanza: All dharmas arise from causes; He has taught the cause of these dharmas. Dharmas cease due to causes; The great teacher has taught the truth of them. 14 When Sariputra heard this stanza, he attained the first fruit of the Path [the state of srotaapanna].

He went back to Maudgalyayana who, noticing the color of his complexion and his cheerfulness, asked him: "Have you found the taste of the Immortal (amrtcirasa)! Share it with me." Sariputra communicated to him the stanza he had just heard. Maudgalyayana said to him: "Repeat it again", and when he had heard it again he also attained the first fruit of the Path.

This bhiksu is named isvajit (in Pali, Assaji) in mosl of '.he Chinese and Pali sources, whereas the Mahavastu (III, p. 60) calls him Upasena. He was one of the five Pancavargiyabhiksu, who were the first to embrace the Buddhadharma (Vinaya, I, p. 13). 14 Free translation of the famous stanza of Pratitj asamutpada, the original Pali of which is in Vinaya, I, p. 40: re (iluanina lietiippahliava tesain lietuin tatliagato aha tesan cayo nirodi < vaim 'in asan <

The Sanskrit is in Mahavastu, III, p. 62: re dharina hetiiprahhava lietun tesain tatliagato alia tesdm cayo nirodho evainvadi inahasrainaiiah. In this form, which goes against the meter, the stanza means: The Tathagata, the truly great ascetic, has proclaimed the cause as well as the cessation of dharmas Shad arise from a cause. - For the interpretation, see Kern, Histoire, I, p. 299-300.

The two teachers, [each] accompanied by 250 disciples went together to the Buddha. Seeing these two men coming with their disciples, the Buddha said to the bhiksus: "Do you see these two men at the head of these brahmacarins?" The bhiksus answered that they saw them. The Buddha continued: "These two men will be foremost among my disciples by their wisdom (prajnd) and by the bases of miraculous powers (rddhipada)." 15 Arriving in the crowd, the disciples approached the Buddha, bowed their head and stood to one side.

Together they asked the Buddha: "We wish to receive, in the Buddhadharma, the leaving of the world (tchou kia = pravrajyd) and higher ordination (cheou kiai = upsampada)." 16 The Buddha said to them: "Come, O bhiksu (eta, bhiksavah)." 11 At once their beards and hair fell off, they were clothed in monks' robes, furnished with the robe (civara) and begging bowl (pdtra), and they received ordination. 18 A fortnight later, when the Buddha had preached the Dharma to the brahmacarin Tch'ang tchao

Here the Mpps follows the version of the Mahavastu, III, p. 63, which h lh< \i nMI) i saying: P hipeti hluksavah asauaiii etc Sariputramaudgalyiiyana parivrajaka paincasataparivara agacchanti tidhagatasyantike brahmacaryam caritum yo me bhavi rut i si ivaaijain ign \ ig > >li uh yugo •/ > igro n ih ipi planum aparo agro inaliarddliikdnam. Tr. - "Set out seats, O monks. Here come the an lori iputi ncl .Ylaudgal i\ ana surrounded by five hundred disciples who are coming to the Tathagata to practice brahmic conduct.

For me they will be an excellent pair of disciples. The first will be the foremost of the great sages; the second will be the foremost of those who have great miraculous powers." This last detail which the Mpps has taken care to note, is absent in the canonical version ( I | which simpl l< ivtikti a i 'no Upatisso ca, etamme savukin in Nun < "< >li \ 16 As did all the first disciples, S. and M. asked for lower ordination (pravrajyd) and higher ordination (upasampadd) al the same time. Later, a period of lour months general!} separated these two ordinations (cf. Kern, Manual, p. 77; Oldcnbcrg, Bouddlia, p. 387 -391 ).

Hie request for ordination is formulated differently in the texts. In Pali: Lahheyyal i ivato si m i (el Pali Vin., I, p. 12, 13, 17, 19, 43, etc.): - in Sanskrit hlieyaln i vakliyate d ivraj) upasampadam < i i i ireyain i igavato " rai (cf. Divya, p. 4 1 J 1 ' ul .1 w h III p i 17 The Buddha ordained the two candidates I / i tda or < iln, ition I in n i -ning: "Come, O bhiksu" (cf Kosa, IV, p. 60). Bui here again the formula varies; in Pali, there is Liu hlukkliu 'ti, wakkluiro illiaiiiino, cara brahmacai i kl i kiriyaya 7i (cf. Pali Vin., I, p. 12, 13, 17, 19, 43, etc.); in Sanskrit, Hi' re is Ehi iku rti hraliinat van 18 Ordination by "Ehi bhiksu" is usually accompanied by the putting on of miraculous robes, of which the Pali Vinaya says nothing, but which is described in stereotyped terms in all the Sanskrit texts:

"The Buddha had no sooner uttered these words than the candidate found himself shaved (munda), clothed in the upper robe i j i i 1 1 \i him ih o I Hid i i / mi i i in In hand etc " (cf. DTvya, p. 48, 281, 341). Here the Mpps is in agreement with the Mahavastu, III, p. 65, and the Molasarv. Vin. (T 1444, k. 2, p. 1028a) in mentioning such a miracle; it also reveals its dependence on the Sanskrit sources. However, although the Pali Vin. says nothing about this taking of the miraculous robes, it is noted in the Dhammapadattha, I, p. 95; but recent research has established that the Ccyloncsc commentaries are also themselves largely derivative from the Sanskrit

(DIrghanakha), Sariputra attained arhathood. 19 Now he who finds the Path at the end of a fortnight should, following the Buddha, turn the wheel of the Dharma (dharmacakra), 20 and in the stage of aspirant (saiksabhumi), penetrate directly (abhimukham) all dharmas and cognize them in all their various aspects (nanakaram).

This is why Sariputra attained arhathood at the end of a fortnight. His qualities (guna) of all kinds were very numerous. And so, although Sariputra was an arhat [and not a bodhisattva], it is to him that that the Buddha preached the profound doctrine (gambhiradharma) of the Prajnaparamita. Question. - If that is so, why does the Buddha preach a little to Sariputra and then a lot to Siu p'ou t'i (Subhuti)? 21 If Sariputra is foremost in wisdom, it is to him he should have mainly preached. Why does he also address himself to Subhuti? Answer. - 1)

Among the Buddha's disciples, Sariputra is the first of the sages {aggo mahapannanam), and Subhuti is the first of those who have attained the concentration of tranquility {aggo aranasamadhivihdrinam). 27 By this practice of tranquility, he ceaselessly considers (samanupasyati) beings in order to prevent them from experiencing any passion whatsoever [for him], and he always practices great compassion (karuna).

This compassion is like that of the bodhisattvas who take the great vow (mahapranidhand) to save beings. This is why the Buddha directs him to teach. [137a] 2) [Suhhuli and Utpalavauid at Sdmkasya]. - Furthermore, Subhuti excels in practicing the concentration of emptiness (sunyatdsamddhi). Having spent the summer retreat (varsa) among the Tao li (Trayastrinsa) gods, the Buddha came down into JambudvTpa. 23 Subhuti, who was then in a rock cave

19 Sariputra had become srotaapanna al the time of his meeting « ilh Asvajit; he became ai hal fifteen days after his ordi lion (ardluan iptisa npaima), at the same time as his uncle DIrghanakha entered the Holy Dharma: cf. Avadanasataka, li. p. 104, treatise, I, p. 51. 20 Sariputra, the second master after the Buddha, the greal leader of the Dharma, turned the \\ heel of the Dharma for the second time; cf. DTvyavadla, p. 394: sa hi dvitiyasasta dhannasciiadlupatir dhannacakrapravartanah prajnavatam agro nirdisto Bliagavata: sec also Sutralamkara, lr. Hibcr, p. 190. 21 In the Prajna literature, Sariputra is the first to question the Buddha, but Subhuti is She main interlocutor. 22

For Subhuti, the foremost of tin vi) i e above, Treatise, I, p. 4F, n. 1 23 After having preached the Abhidharma for three months to his mother, the Buddha "came down from the Trayastrimsa heaven to JambudvTpa in the city of Samkasya, into the Apajjura enclosure at the foot of the Udumbara (a\ van de\ liyah sain I I ihai amule).The Devavatara is often represented on the monuments: Cunningham, Barlnit. p: 17: Marshal! -toucher, Man. ofSanchi, II, pi. 34c);

Majumdar, G. to Sarnath, pi. 13e; Vogel, Mathurd, pi 51a I < n hut i / ; ' |>l II d: Griffiths, Ajanta, pi. 54. According to one version, welcomed on his descent from the heaven by a great assembly, the Buddha was first greeted by Sariputra (Dhammapadattha, 111. p. 226), immediately followed by the nun Utpalavarna (Suttanipata Comm. II, p. 570). According to the Tibetische Lebensbescreibung, tr. Schicfncr, p. 272, Udayana, king of KausambI, received him ceremonially. An apparitional (upapaduka) bhiksu invited the Buddha along with the assembly of bhiksus and devas to a splendid repasl (Tsa a han, T 99, k. 19, p. 134c; Avadanasataka, II, p. 94-95; Po yuan king, T 200, k. 9, p. 247a-b). According to some sources, the nun (Jtpalavarna, in order to be the first to greet the Buddha, magically transformed herself into a cakravariin king surrounded bj his thousand sons: Cf. Divyavadana, p. 401: yaddpi,

(sailaguhd), said to himself: "The Buddha is descending from the Trayastrimsa heaven; should I or should I not go to him?" Again he said to himself: "The Buddha has always said: 'If someone contemplates the dharmakaya of the Buddha with the eye of wisdom (prajndcaksus), that is the best way of seeing the Buddha.'"

Then when the Buddha descended from the Trayastrimsa heaven, the four assemblies of JambudvTpa had gathered; the gods saw the people and the people saw the gods; on the platform were the Buddha, a noble cakravartin king and the great assembly of the gods: the gathering (samaja) was more embellished (alamkrta) than ever before. But Subhuti said to himself: "Even though today's great assembly is quite special (visista), its power (prabhava) will not last for a long time.

Perishable dharmas (nirodhadharma) all return to impermanence (anityata) ." Thanks to this consideration of impermanence (anityatdpanksd), he understood that all dharmas are empty {sunya) and without reality (asadbhiita). Having made this consideration, he at once obtained the realization of the Path (mdrgasdksdtkdra). At that moment, everyone wanted to be the first to see the Buddha and to pay their respect (satkdrd) and homage ipujd) to him. In order to disguise her disreputable sex, the bhiksunl Houa so (Utpalavarna) transformed herself into a noble cakravartin king with his seven jewels and his thousand sons. When people saw him, they left their

inaharaja, Bhagarata dcrcsu trayastriiiiscsa varsa usitvd inatur jaiuiyitrya dhannam dcsayitva dcraganaparivrtah Sdmkdsye naga i \ i Utj ilavarnayd ca nirmita cakravi I Sec also the Legend of Asoka (Tsa a han, T 99, k. 23, p. 169c; T 2042, k. 2, p. 105b; T 2043, k. 3, p. 140b), the Dulwa (Rockhill, Life, p. 81) and the comment of Fa hien (tr. Legge, p. 49). A panel of the Loriyan-Tangai rcprodti iny ill D ivatara sho\ i ki rtii I mi nonnl d on an elephant, "a disguise assumed by the nun Utpalavarna for the occasion" (Toucher, Art Grcco-hoaddhique, I, p. 539, fig. 265). -

The commentary of the Karmavibhahga, p. 159-160, adds that the Buddha reproached her for her excessive zeal, for, said he, "It is not by means of homage rendered to my body that was born from my parents that I am truly honored": i i, ' i i < iii^i i Bliagava valokavatii prathainam va i a tustd mayd Bhagavdn prat, i , i yds ca tarn jnatva si or , u etad darsayati. na t taut vaiidito hhavdmi. vena phalam praptani tc nclham vanditah. tad irtliam va c, tatra gitthi ta ttiaiiu vapratil thlieiia svarganani gamanaia ca prthivydm ekardjyaiti ca -.<otapattiphala.mpa.ram. anaiapi karijata dliar/ita era Bliagavatalj sanraiii. Yet other texts - and the Mpps is among them - establish a parallel bctw ecu Utpahn arna and Subhuti.

This bhiksu, instead of going to greet the Buddha on his descent from the heaven, remained quietly in his retreat at Rajagrha where he was meditating on impermanence and the futility of things. He was thus paying homage to the dharmakaya. As this meditation greatly overshadowed the salutations addressed by Utpalavarna to the Buddha's birth-body (janmakdya), it was said that Subhuti and not Utpalavarna had been the first to greet him. Cf. Tseng yi a han, T 125, k. 28, p. 707cl5-708a20; Yi tsou king, T 198, k. 2, p. 185c; T tch'eng tsao siang kong to king, T 694, k. 1, p. 792c-793a; Fen pie kong to louen, T 1507, k. 3, p. 37c-38a; Si yu ki, T 2087, k. 4, p. 893b (tr. Beal, I, p. 205; Walters, I, p. 334). 24 This rock cave, adorned with jewels, is on the Gidhi I i ip n ita n u Rajagrha cf. Tseng yi a han, T 125, k. 6, p. 575bl-2;k. 29, p. 707cl2.

seats and moved away [to give him place]. When this Active king came near the Buddha, he resumed his former shape and became the bhiksunl again. She was the first to greet the Buddha. However, the Buddha said to the bhiksunl: "It is not you who has greeted me first; it is Subhuti. How is that? By contemplating the emptiness of all dharmas, Subhuti has seen the dharmakaya of the Buddha; he has paid the true homage (puja), the excellent homage. To come to salute my birth-body (janmakaya) is not to pay homage to me." 25 This is why we said that Subhuti, who ceaselessly practices the concentration on emptiness, is associated (samprayukta) with the Prajnaparamita, empty by nature.

For this reason, the Buddha entrusted Subhuti to preach the Prajnaparamita. 3) Finally, the Buddha entrusted him to preach it because beings have faith in the arhats who have destroyed the impurities (ksTnasrava): [thanks to them], they obtain pure faith (prasada). The bodhisattvas have not destroyed the impurities and if they were taken as evidence (sdksiri), people would not believe them. This is why the Buddha conversed about the Prajnaparamita with Sariputra and Subhuti. IV. ORIGIN OF SARIPUTRA' S NAME (636F) 26

Question. - Where does the name Sariputra come from? Is it a name given [to Sariputra] by his father and mother, or is it a name coming from some meritorious action that he had accomplished? Answer. - It is a name given to him by his father and mother.

In JambudvTpa, in the very fortunate [region], there is the kingdom of Mo k'ie t'o (Magadha); there is a great city there called Rajagrha; there was a king there named P'inp'o so lo (Bimbisara) and a brahmin, master of teaching (upadesd) [137b] named Mo t'o lo (Mathara). Because this man was very skillful in debate, the king had given him as a privilege a large village situated not far from the capital. This Mathara married and his wife bore a daughter; because the eyes of this young girl resembled those of the Cho li (sari, the heron) bird, she was called Sari; later the mother bore a son whose knee-bones were very big, and for that reason he was called Kiu hi lo (Kausthila).

After this brahmin married, he was busy raising his son and daughter; he forgot all the holy books he had studied and he did not put his mind to acquiring new knowledge. At that time, there was in southern India, a brahmin, a great master of teaching, named T'i cho (Tisya); he had penetrated deeply into the eighteen kinds of great holy books. This man came to the city of Rajagrha; on his head he was carrying a torch 27 and his belly was covered with copper sheets; when he was asked the

This is also what the Buddha said to Vakkali (Samyutta, 111, p. 120): "What is the use of seeing this body of rottenness {putikaydfl He who sees the Dharma sees me..." 26 This paragraph has been translated b\ Cha\ amies, Contes, III, p. 290-294, (he translation of which is reproduced here. - Sariputra, also called Upatisya, was the son of Tisya and Sari. The latter's father was Mathara, a brahmin I) ii i I aid md her broth i vlahakausthila urnamed Dirghanakha. CI vlulasan in. I I Hilt, digit Us of the Vinaya Pitaka, IHQ, SIV, 1938, p. 422-423; Ken pen chou... tch'ou kia che, T 1444, k. 1, p. 1022b seq.; Rockhill, Life, p. 44): Avadanasataka, II, p. 186; Po yuan king, T 200, k. 10, p. 255a; Treatise, I, p. 47-51F. 27 On the theme of the brahmin w ho earrics a torch in full daylight, see Chavanncs, Contes, I, p. 392-393.