The Inner Kālacakratantra - A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual: The Social Body

The Inner Kālacakratantra

A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual

A. Wallace

The Cosmic Body

The Cosmos, the Individual, and the Cosmos as the Individual The Kālacakratantra's cosmology is structured on several theoretical models. In its interpretation of the conventional nature of the cosmos, the Kālacakratantra combines to some degree the Vaibhāṣika atomic theory, the Sāṃkhya model of the twenty-five principles of the puruṣa and prakṛti, and Jaina and Purāṇic cosmographies with its own measurements of the cosmos (loka-dhātu) 1 and its own theories of the cosmos's nature and relation to the individual. The Kālacakra tradition intentionall y uses this form of syncretism in order to provide a useful theoretical model of the Buddhist tantric view of the cosmos that will accord with its interpretation of the individual and with its model of practice.

As already indicated in chapter 3 on syncretism, the Kālacakra tradition itself justifies this syncretism in terms of its proselytizing efforts 2 and in terms of the multiplicity and relativity of conventional realities. According to this tantric tradition, knowledge of the constitution of the cosmos and of the manner in which the cosmos originates and dissolves is pertinent to one's spiritual maturation. The Vimalaprabhā explicitly states that in order to fully comprehend the three Vehicles, one must first know the origination and dissolution of the cosmos as taught by the Vaibhāṣikas, who assert the true existence of the individual (pudgala) and of the cosmos, which consists of an agglomeration of atoms. 3 While supporting the Madhyamaka view of phenomenal and personal identitylessness, the Kālacakra tradition affirms the conventional existence of the cosmos and the individual and acknowledges the validity and usefulness of the Vaibhāṣikas' atomic th eory of the evolution and disintegration of the cosmos. Consequently, it holds that within the context of the Kālacakra system, one investigates the conventional nature of the cosmos by way of the Vaibhāṣika doctrine and gains a thorough knowledge of the three Vehicles, thereby enhancing one's understanding of the entire Buddhist Dharma. Resorting to the Vaibhāṣika atomic theory, the Kālacakratantra asserts that all inanimate phenomena that constitute the cosmos originate from atomic particles that evade sensory perception—namely, the atoms of the earth, water, fire, wind, and space elements, which are pervaded by the sphere of reality (dharma-dhātu). 4 Likewise in the case of the individual, the atomic particles of earth, water, fire, wind, and space that form the father's seminal fluid and the mother's uterine blood eventually become the body of the individual. 5 Thus, the inanimate phenomena in the individual's body and environment share the same atomic structure and originate in a similar fashion by means of the agglomeration of atomic particles, which takes place due to the efficacy of time. This is one way in which the Kālacakra tradition attempts to demonstrate that the individual and the individual's natural environment are identical not only with regard to their ultimate nature, but also with regard to their conventionally established atomic structure and their manner of origination and destruction.

The Origination and Dissolution of the Cosmos and the Individual

According to the Kālacakratantra, 6 cyclic existence consists of the immeasurable Buddha-fields (buddha-kṣetra), which have limitless qualities, and of the five elements. It is characterized by their origination, duration, and destruction. This entire cosmos is said to arise and dissolve because sentient beings are experiencing the results of their wholesome and unwholesome actions. The collective karma of sentient beings produces karmic winds, which mold and dissolve the cosmos by amassing and disintegrating the atomic particles that constitute the cosmos. Thus, the external karmic winds (karmavāta) accord with the characteristic qualities of sentient beings' consciousness (vijñāna-dharma). The karmic wind that produces the cosmos of a Buddha-field is considered to be of a dual nature, because it produces two types of cosmos: inanimate and animate. Like the heavenly constellations (nakṣatra), the inanimate cosmos of a Buddha-field is stationary; whereas the animate cosmos is in motion, just as the circle of astrological houses (rāśi-cakra) moves in space.

At the time of the dissolution of the inanimate cosmos, the bodies of all humans and other living beings composed of atoms also disintegrate. In this way, the destiny of the inanimate cosmos, which is due to the actions of sentient beings, is also the destiny of the sentient beings who inhabit that cosmos. The limitless karmic winds generate the numerous world-systems of the Buddhafields just as the karmic winds of the prāṇas, which invariably accompany a transmigratory consciousness, generate the body of a sentient being. Just as the internal karmic winds of living beings induce bodily growth, the external karmic winds cause the growth of inanimate things. 7 There are three types of external karmic winds: the holding (samdhārana), churning (manthāna), and shaping (saṃsthāna) wind. The supporting wind holds together the atoms of the earth and the other elements in the same way that a rain-wind holds together the atoms of rain-water. Following that, the churning wind churns the atoms to their very core until the elements become solidified. Just as salt crystallizes due to its exposure to the sun, the elements solidify due to such churning. The churning wind makes the elements absorb each other into the agglomerate in which the atomic particles of one element become a predominant substance, while the atomic particles of other elements become secondary substances. As in a human body so too in the cosmos, with regard to solidity, the atoms of the earth become primary and the other atoms secondary. Likewise, the water, fire, and wind elements become primary in terms of fluidity, heat, and motility, respectively. In the case of space, however, all other atomic particles that are devoid of their own properties become primary. 8 Once the agglomeration of the atomic particles of the elements takes place, the great shaping wind moves through the entire Buddha-field in the form of the ten winds. 9 These ten karmic winds that fashion the inanimate cosmos also shape the body of the individual, in which they circulate and carry the habitual propensities of the individual's karma.

Therefore, one can say that for this tantric tradition, all karma of sentient beings is stored in the atomic particles of the karmic winds. The Kālacakratantra itself asserts that “one's own karma is contained in the guṇas of prakṛti, ” 10 which is conventionally established as physical. It also indicates that the ten karmic winds, which fashion the inanimate environment and the body of the individual, themselves arise from the five elements. The three winds of āpāna arise from the gnosis-element, and the three winds of prāṇa arise from the space-element. Samāna arises from the wind, udāna arises from the fire, vyāna arises from the water, and nāga arises from the earth. These four—kūrma, kṛkara, devadatta, and dhanamja—arise respectively from the wind, fire, water, and earth. 11 In the final analysis, this suggests that the karma of sentient beings, which manifests in the form of atomic substances, is of a physical nature. In this regard, the Kālacakratantra's view of karma conforms to the Jaina theory of karma as subtle clusters of matter that constitute a karmic body.

In the Kālacakra tradition, however, this view of karma does not preclude the traditional Buddhist view of all actions as being ultimately mental. Even when the Kālacakra tradition acknowledges that one's own trans migratory mind (saṃsāra-citta) is a conventionally established agent of all actions and a fundamental cause of the origination and destruction of the entire cosmos, it specifies that the five elements are the material components of the trans migratory mind. It does so pointing to the fact that the agent who is devoid of material substances neither acts nor creates anything. 12 Thus, one may infer that karma is material, because the trans migratory mind that generates it is itself material.

Likewise, all cyclic existence, which manifests due to sentient beings' karma, is material because the karma that creates it is itself material. I surmise that this causal relationship among the material nature of the trans migratory mind, karma, and the environment that one perceives is implied in the Kālacakratantra's assertion that the cosmos that one perceives is a mere manifestation of one's own mind. According to this tantric tradition, a Buddha-field always comes into existence accompanied by a world-system, just as the origination of the individual's body is always accompanied by the seventy two thousand nāḍīs. 13 At the time of the origination of the cosmos, very subtle particles (aṇu), which are imperceptible to the sense faculties, are said to be present in the form of atomic particles (paramāṇu). These atomic particles are of the five types: wind, fire, water, earth, and space. Under the influence of time, the wind-element originates first among these atomic particles. This origination begins with the atomic particles of wind adhering to each other. Then, owing to their adherence, a subtle fluttering motion takes place, and this we call “wind. ” After that, the atoms of fire begin to adhere to one another, and lightning, accompanied by wind, comes forth as fire. Following this, the atoms of water adhere to one other, and rain, accompanied by the wind and fire, comes into existence as water. Lastly, the atomic particles of the earth-element appear, and a rainbow called “earth” arises in space. The atoms of space pervade all of the above mentioned elements. Upon the formation of the five elements, the seven continents, mountains, and oceans start to arise from the five elements due to the conjunction of the supporting, churning, and shaping winds. 14 The seven mountains and the seven continents arise from the earth-element, which is solidity.

The seven oceans arise from the water element, which is fluidity. The fire of the sun, lightning, and domestic fire originate from the fire-element, which is heat. The wind-element is motility, and the space element is the domain that allows for movement and growth. This is the manner in which the entire cosmos arises from the atomic particles of the five elements in order for sentient beings to experience the results of their actions. At the time of the dissolution of the cosmos, the fire that burns the cosmos to ashes (kālāgni), kindled by the winds of karma, melts the atomic agglomerates of the entire cosmos. Its function is comparable to the fire of gnosis (jñãnãgni), or the fire of sexual desire (kāmāgni), which incinerates the material nature of the trans migratory body and consciousness during the completion-stage of Kālacakratantra practice. It is also worth noting that both fires—kālāgni and kāmāgni—are identified in this tantric tradition as two types of deities, namely, Kālāgni and Caṇḍālī. 15

Their respective locations in the cosmos and the body of the individual are also comparable, since both dwell in the lower regions of the cosmic and individual bodies, where they can become aroused or ignited. Kālāgni dwells in the underworld, and Caṇḍālī abides in the navel of the human body. Caṇḍālī flames due to the constriction of the winds of prāṇa, and it is therefore called “the fire of prāṇāyāma. ” 16 Similarly, kālāgni inflames when the karmic winds of the prāṇas of the cosmic body are extinguished. The time of the incineration of the cosmos is characterized not only by the destruction of the cosmos but also by its origination. At the time of the disintegration of the cosmos, the atomic particles of the earth-element do not perish; they remain due to their cohesion with the atomic particles of the water and other elements.

When the cosmos dissolves, a karmic wind draws out the atoms of the earth from their agglomerates, separating the individual atoms from the mass of earth atoms and hurling them into the mass of the water atoms. Following this, it draws them out of the water-element and hurls them into the fire-element. Then it draws them out of the fire-element and hurls them into the wind-element. Lastly, it draws them out of the atomic particles of the wind-element and spreads them one by one into space. Upon the destruction of the inanimate cosmos, living beings go to another Buddhafield and to another cosmos, which are produced by their karmic winds, in order to experience the further results of their actions. The manner in which the inanimate cosmos originates and dissolves corresponds to the manner in which a human being comes into existence and dies. As in the inanimate world, the human body, due to the power of the ten karmic winds, arises from the agglomerations of atomic particles of the earth, water, fire, wind, and space elements. At the time of conception, the father's semen and mother's uterine blood, which are made of the five elements, are “devoured” by the consciousness which, accompanied by subtle prāṇas, enters the mother's womb. When conception takes place due to the power of time, the semen and uterine blood within the womb slowly develop into the body of the individual. This occurs due to the spreading of prāṇas. The growing fetus consumes food comprised of six flavors—bitter, sour, salty, pungent, sweet, and astringent—and these six flavors originate from the six elements, sixth being gnosis. Consequently, the body of a fetus becomes a gross physical body, composed of the agglomerates of the atomic particles. The elements of the father's semen give rise to the marrow, bones, nāḍīs, and sinews of the fetus; and the elements of the mother's uterine blood give rise to the skin, blood, and flesh of the fetus.

Thus, all the elements and psycho-physical aggregates that constitute the human being come into existence due to the union of the atomic agglomerates of the father's semen and mother's uterine blood. The five elements of the father's semen and mother's uterine blood facilitate the growth of the fetus, just as they facilitate the growth of a plant's seed in the natural environment. The earth-element supports the semen that has entered the womb, just as it holds a seed in the ground; and the water-element makes it sprout from there. The fire-element makes it blossom and digest the six flavors that arise from the six elements. The wind-element stimulates its growth, and the space-element provides the room for growth. The earth-element causes the body to become dense, and it gives rise to the bones and nails. The water element causes moisture in the body, giving rise to the seven kinds of bodily fluids. The fire-element induces the maturation of the fetus and gives rise to blood. The ten principal winds of prāṇas expand its skin, and the space-element becomes the bodily apertures. On the basis of these similarities in atomic nature of the inanimate world and the body of the individual, the Kālacakra tradition identifies the seven mountains, continents, and oceans with the elements of solidity, softness, and fluidity in the body of the individual.

Tables 5. 1.a—c illustrate the correspondences among the seven mountains, continents, and oceans and the specific constituents of the human body. After the moment of conception, the semen and uterine blood grow in the womb for a month. Following this, the ten subtle nāḍīs arise within the heart of the fetus. Likewise, within the navel, there arise the sixty-four nāḍīs that carry the daṇḍas in the body and the twelve subtle nāḍīs that carry the twelve internal solar mansions. Due to the prāṇas' power of spreading, all the nāḍīs in the navel gradually expand into 60- the regions of the arms, legs, and face. After the second month, there are some indications of arms, legs, and a face. At the end of the third month, the arms, legs, neck, and the whole head are clearly developed.

The five fingers of each hand and the five toes of each foot arise respectively from the five elements. 17 During the fourth month, subtle nāḍīs spread into the hands, feet, face, and neck, and during the fifth month, three hundred and sixty bones and joints begin to develop within the flesh. At the completion of the sixth month, the fetus is endowed with flesh and blood, and it begins to experience pleasure and pain. At the completion of the seventh month, the bodily hair, eyebrows, bodily apertures, and remaining nāḍīs come into existence. At the end of the eighth month, the joints, bones, marrow, tongue, urine, and feces are fully developed. The complete body is said to consist of 20.5 million constituents, for there are that many modifications of the five elements of the father's semen and the mother's uterine blood. During the ninth month, the fetus experiences pain as if it were being baked in a potter's oven. At the completion of the ninth month, one is born, being squeezed by the womb and experiencing pain as if one were being crushed by an anvil and a hammer.

Thus, propelled by the habitual propensities of one's own karma, which are carried by the ten internal winds of prāṇas, a human being enters the world that is likewise brought into existence by his own karma, which, again, is carried by the ten external winds of prāṇas. Thus, the cosmos and the individual share a common material nature and common causes of origination and destruction. They also originate in similar ways, with their respective components arising in the same sequence. Table 5.2 illustrates the correspondences between the origination of the specific bodily parts and the various parts of the cosmos. 18

A classification of the different components of the human and cosmic bodies into the sequentially arising sets of the four, five, six, four, five, and three, as presented in table 5.2, is used in this tantric tradition as a model for practicing a sādhana on the sequence (krama) of the arising of the five tantric families (kula) within a larger bodily or cosmic family. Just as a sequence of the origination of the diverse parts of the cosmos corresponds to that of the individual, so too does the sequence of the dissolution of the cosmos accord with that of the individual. In the process of the dissolution of the cosmos, the karmic winds that support the elements sequentially withdraw from the agglomerates of the five elements in the five cosmic discs that make up the cosmos. Similarly, in the process of dying, the winds of prāṇas sequentially cease carrying the elements of earth, water, fire, wind, and space within the respective cakras of the navel, heart, throat, lalāṭa, and uṣṇīṣa. 19

According to the Kālacakra tradition, one's own body, which was produced by one's own karma from the material particles of the father's semen, also dissolves due to the emission of one's own semen. At a human's death, semen, which consists of the five elements, flowing out of the dead body initiates the disintegration of the body. Several passages on this topic in the Kālacakra literature suggest that semen leaves the body at the time of death due to the power of the individual's habitual propensities of seminal emission in sexual bliss. The habitual propensities (cittavāsanā) of the mind of the human being, who consumes the food of the six flavors that originate from the five elements, themselves consist of the five elements. Therefore, semen, which leaves the body during the experience of sexual bliss and at death, is composed of the five elements.

At the time of death, the habitual propensities of the mind, together with semen, upon leaving the dead body, make up the body of the habitual propensities (vāsanā-śarīra) of the mind. Even though this body of the habitual propensities of the mind is made of fine atomic particles, it is similar to a dream body (svapna-śarīra), in the sense that it is devoid of perceptible agglomerations of atoms. The body of the habitual propensities of karma does not cease at death. Due to this remaining body of habitual propensities, a trans migratory consciousness acquires a new gross body consisting of atoms. As a trans migratory consciousness forsakes the habitual propensities of the former gross body, the habitual propensities of the new gross body arise in the mind. Consequently, the adventitious psycho-physical aggregates (āgantuka-skandha) arise from the empty (śūnya) psycho-physical aggregates of the habitual propensities of the mind (citta-vāsanā-skandha). Likewise, the empty psycho-physical aggregates of the habitual propensities of the mind arise from the adventitious psycho-physical aggregates. The atomic particles of the former, dead body do not go to another world, for after leaving the earlier psycho-physical aggregates, a trans migratory consciousness acquires different atomic particles. 20

This process of rebirth is said to be the same for other sentient beings of the three realms of cyclic existence. The only difference is in the number of the elements that constitute the bodies of the diverse classes of gods. Instead of having five elements, the bodies and semen of the gods in the desire-realm, form-realm, and formless realm consist of four, three, and one element, respectively. This is because gods consume food that consists of five, four, or one flavor. For example, the bodies and semen of the gods inhabiting the six types of desire-realm consist of the agglomerations of the elements of water, fire, wind, and space. The bodies of these gods are devoid of the earth-element and are therefore characterized by lightness. Likewise, their mental habitual propensities are devoid of smell as the sense-object that arises from the earth-element.

The bodies and semen of the sixteen types of gods dwelling in the form-realm consist of the agglomerations of the atoms of fire, wind, and space; and their mental habitual propensities are endowed with taste, touch, and sound as their sense-objects. The bodies and semen of the gods inhabiting the formless realm consist of the space-element alone, and their mental habitual propensities have only sound as their sense-object. 21 Thus, the bodies, mental habitual propensities, and experiences of different sentient beings are closely related to the nature of the elements contained in the semen with which they undergo birth and death. According to this tantric system, a habitual propensity of trans migratory existence cannot arise from a single attribute of the elements but only from an assembly of attributes. In the case of all sentient beings dwelling in the three realms, during sexual bliss and at death, semen—the elements of which may be the five, four, three, or one in number—leaves the body under the influence of the habitual propensities. In this way, seminal emission is instrumental in both the birth and death of sentient beings. For the Kālacakra tradition, the cycle of birth and death does not take place in any other way. Thus, one may say that for this tantric tradition, the entire cosmos, with all of its inhabitants, manifests and dissolves due to the power of the moment of seminal emission.

The Configuration and Measurements of the Cosmos and the Individual

Since the entire cosmos comes into existence due to the efficacy of the habitual propensities of sentient beings' minds, one may regard it as a cosmic replica of sentient beings' bodies. Thus, the configuration and measurements of the cosmos are seen in this tantric system as analogous and correlative to the structure and measurements of the individual's body. Likewise, since the cosmos arises and dissolves as a manifestation of the individual's mind, the Kālacakratantra considers the cosmos as being fundamentally nondual from the individual. Due to their common material nature, the cosmos and the individual are viewed as mutually pervasive, even in terms of their conventional existence; and due to their fundamental nonduality, the cosmos and the individual inevitably influence each other. In terms of conventional reality, the cosmos and the body of the individual are nondual in the sense that they share a common nature (prakṛti) consisting of the twenty-four principles (tattva), which are the objects of the individual's (puruṣa) experience.

The eight constituents of the primary nature (prakṛti) of the individual— namely, the five elements, the mind (manas), intellect (buddhi), and self-grasping (ahaṃkāra)—are the microcosmic correlates of the primary nature of the individual's environment. Likewise, the sixteen modifications (vikṛti) of the primary nature of the individual—specifically, the five sense-faculties, the five sense-objects in the body, the five faculties of action, and the sexual organ —evolve from the primary nature of the individual in the same way that the five planets, five external sense objects, and six flavors evolve from the primary nature of the cosmos. In terms of ultimate reality, the cosmos and the individual are also of the same nature, the nature of gnosis (jñāna), which manifests in the form of emptiness (śūnyatā-bimba).

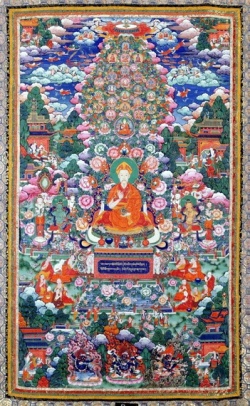

Those who are free of the afflictive and cognitive obscurations nondually perceive the world as the form of emptiness in a nondual manner; that is, they perceive the world as an inseparable unity of form and emptiness. On the other hand, ordinary sentient beings, whose perception is influenced by the afflictive and cognitive obscurations, see the world in a dual fashion, as something other than themselves. They see the world as an ordinary place inhabited by ordinary sentient beings. But in reality, the entire cosmos, with Meru in its center, is a cosmic body of the Jina, a cosmic image or reflection (pratimā) of the Buddha, having the nature of form. As such, it is similar to the Nirmānakāya of the Buddha. 22 Therefore, according to this tantric system, one should attend to this cosmic image of the Buddha, as one attends to the statue of the Buddha, created for the sake of worship.

The immediate aim of the Kālacakratantra's exposition of the interrelatedness of the individual and the cosmos is not to directly induce the unmediated experience of their nonduality by eradicating the afflictive and cognitive obscurations, but to facilitate a thorough understanding of conventional reality. In this tantric system, a proper understanding of the structure and functions of conventional reality provides a theoretical basis for the realization of ultimate reality.

I see two main reasons for this. First, conventional reality is the starting point from which a tantric practitioner ventures into tantric practices; and second, a thorough knowledge of the ways in which conventional reality operates facilitates insight into the nature of conventional reality, which is fundamentally not different from ultimate reality. Before one can understand the nonduality of conventional and ultimate realities, one must first understand that a seemingly multiform conventional reality is itself unitary.

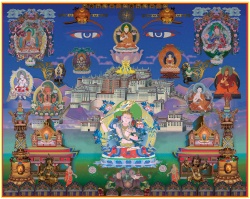

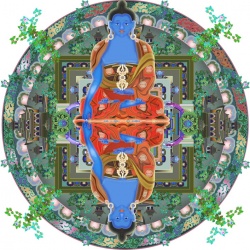

This, I surmise, is one of the reasons why the Kālacakratantra's initial two chapters are dedicated to discussions of the ways in which the cosmos and the individual correlate to and pervade each other. “As it is outside so it is within the body” (yathā bāhye tathā dehe) is one of the most frequently used phrases in the Kālacakratantra and its commentarial literature. This maxim underlies the pervading themes of the Kālacakratantra's chapters on the cosmos and the individual. To the phrase “as it is outside so it is in the body, ” the Ādibuddhatantra adds “as it is in the body so it is elsewhere” (yathā dehe tathā anyatra), meaning, in the kālacakra-maṇḍala. 23 The cosmos, the human body, and the kālacakra-maṇḍala are taught here in terms of conventional truth as three maṇḍalas representing the outer (bāhya), inner (adhyātma), and alternative (anya), or sublimated, aspects of a single reality. Therefore, these three maṇḍalas are said to be the three abodes of the Buddha Kālacakra. Knowledge of how these three conventional aspects of ultimate reality are interrelated is seen as soteriologically significant, for such knowledge provides an indispensable theoretical framework for Kālacakratantra practice, which aims at the unmediated experience of their fundamental unity. It is for this reason that the Kālacakra literature frequently points out the correlations among the arrangements and measurements of the cosmos, the human body, and the kālacakra-maṇḍala.

There is sufficient textual evidence in the Kālacakra literature to indicate that the Kālacakratantra refers to these three aspects of reality as circular maṇḍalas, not because it considers a circular form to be their true form, but merely as a heuristic model for meditative purposes. In showing the parallels among the cosmos, the human body, and the Kālacakra-maṇḍala, the Kālacakra tradition uses various paradigms, which reflect the diverse ways in which this tantric tradition interprets the cosmos as a cosmic body of the individual and of enlightened awareness. All the diverse models of the relations between the cosmos and the individual that the Kālacakra tradition provides have a practical purpose: they serve as devices for furthering one's understanding of the interconnectedness of all phenomena and for training the mind to perceive the world in a nondual fashion. Moreover, they are the contemplative models with which one can diminish the habitual propensities of an ordinary, dualistic mind. The configuration and measurements of the cosmos as described in the Kālacakratantra frequently differ from those given in the Abhidharmakośa.

The Kālacakra tradition departs from the Abhidharmakośa not only with regard to the arrangement and size of the cosmos but also in terms of the units of measurements. 24 Nevertheless, the Kālacakra tradition does not attempt to authenticate its own presentation of the arrangement and measurement of the cosmos over that given in the Abhidharmakośa. The Vimalaprabhā 25 asserts that in terms of the ultimate truth, the cosmos has no spatial dimensions. The conventionally established size of the cosmos appears differently to different sentient beings due to the power of their virtue (puṇya) and sin (pāpa). The cosmos is merely an insubstantial apparition of the mind, like a five cubits wide cave inhabited by a śrāvaka or a Bodhisattva due to whose powers a universal monarch (cakravartin) and his army can enter the cave without the cave being extended and without the universal monarch's army being contracted. Similarly, the Kālacakratantra 26 itself asserts that for the Buddhas and for knowledgeable people, the dimensions of the cosmos that were taught by the Buddhas are not its true dimensions, since for the Buddha, one cubit can be many cubits due to the power of the Sahajakāya. It also affirms that the Buddha reveals only the dimensions that corresponds to the perceptions of sentient beings, because if he were to say that the dimensions of the cosmos which he taught were in accordance with the inclinations of living beings dwelling in the land of karma (karma-bhūmi), then the gods would call him a nihilist (nāstika). Thus, the Kālacakra tradition implicitly suggests that

both Buddhist accounts of the configuration and size of the cosmos—those of the Abhi-dharmakośa and the Kālacakratantra—are ultimately invalid. Nevertheless, it considers both accounts to be provisionally valid expressions of the Buddha's skillful means. Justifying the Kālacakratantra's account of the dimensions of the cosmos in terms of skillful means, the Vimalaprabhā cites the following verses from the Paramādibuddhatantra: A falsehood that benefits sentient beings causes an accumulation of merit. A truth that harms others brings Avici and other hells.

Miserly pretas perceive a homely dwelling as a mountain. Evil-doers perceive a home in the form of a needle-pointed mountain.

Siddhas who have attained the siddhi of the underworld perceive the solid earth as full of holes everywhere and visit the city of celestial nymphs (apsaras). 27 In a similar manner, the following verse from the abridged Kālacakratantra 28 expresses its view that one's perception of one's own natural environment is relative, for it is conditioned by the degree of one's own virtue and sin. Wish-fulfilling trees, quicksilver, supreme potions, other medicinal herbs, and philosopher's stones, which eliminate all diseases, appeared on the earth along with atoms. However, sentient beings do not see them. They see ordinary grass, trees, water, dust, stones, and copper. Pretas perceive rivers as blazing fires, and men in hell perceive spears and other weapons. In this way the Kālacakra tradition interprets the disparities in the measurements and arrangement of the cosmos within the two Buddhist traditions as evidence of the diversity of sentient beings' perceptions and experiences of the cosmos, which results from their diverse mental dispositions and actions. However, this same interpretative principle is not applied to the divergent measurements of the cosmos given in Hindu Siddhāntas. The Vimalaprabhā denies even the conventional validity of the Hindu view of the cosmos as Brahmā's egg (brahmāṇḍa), ten million leagues (yojana) in size.

In light of its criticism of the Hindu Siddhāntas, the Vimalaprabhā claims that the Kālacakratantra establishes the size of the cosmos using the zodiacal circle (rāśigolā) for the calculation of planets in order to abolish the Hindu measurements of the cosmos for the sake of the spiritual maturation of Buddhist sages. 29 According to the Kālacakratantra, within every single world-system (loka-dhātu) there is one great world system (cakravāla), just as on every single body of a human being there are bodily hairs and skin. The world-system that is of the nature of karma is in the center of a Buddha-field, just as the avadhūti is in the center of the body among all the nāḍīs. The remaining world-systems that are of the nature of enjoyment (bhoga) stand in the same relation to the land of karma (karma-bhūmi) as do the other nāḍīs to the avadhūti. These lands of enjoyment (bhoga-bhūmi) bring pleasure to the senses, as do the nāḍīs in the body. They are filled with jewels, as the nāḍīs are filled with blood. Vajrasattva, the progenitor of the three worlds, dwells in space until the time of expansion of the cosmos. But sentient beings do not witness the arising of the Buddha as long as they lack the accumulations of merit and knowledge. During the time when sentient beings lack merit and knowledge, Vajrasattva resides in space, abiding in the Dharmakāya; and by means of the Jñānakāya, he perceives the entire Buddha-field as it truly is, free of karma and karmic winds. 30 It is said that Vajrasattva, together with all other Buddhas, abides in a single pure atom (śuddhāṇu), which is not of the nature of an atomic particle (paramāṇu) but of the twelve bodhisattvabhūmis. 31 Thus, while ordinary sentient beings, endowed with afflictive and cognitive obscurations, have atomic particles as their material support, the Buddhas, free of all obscurations, have the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis as their pure, immaterial support. In other words, that which is perceived as an agglomeration of atomic particles by those with mental obscurations is perceived as pure gnosis by those without obscurations. Even though the Kālacakratantra agrees to some extent with the Abhidharmakośa about the manner in which the cosmos evolves, its description of the configuration and measurements of the cosmos differs significantly from that of the Abhidharmakośa.

According to the Kālacakra tradition, the cosmos measures twelve hundred thousand leagues in circumference and four hundred thousand leagues in diameter. 32 It is composed of the five maṇḍalas, or the five discs (valaya)—namely, the earth, water, fire, wind, and space maṇḍalas—just as the human body is composed of the five elements. These maṇḍalas support one another in the same sequence in which the five elements support one another in the body. 33 Although each of the first four maṇḍalas measures fifty thousand leagues in height, they vary in diameter and circumference. The earth maṇḍala, measuring one thousand leagues in diameter, or three hundred thousand leagues in circumference, rests on the water-maṇḍala. The water-maṇḍala, measuring two hundred thousand leagues in diameter, or six hundred thousand leagues in circumference, rests on the fire-maṇḍala. The fire-maṇḍala, measuring three hundred thousand leagues in diameter, or nine hundred thousand leagues in circumference, rests on the wind-maṇḍala. The wind-maṇḍala, measuring four hundred thousand leagues in diameter, or twelve hundred thousand leagues in circumference, rests on the sphere of space (ākāśa-dhātu). Thus, space is the support of all the maṇḍalas, just as it is the support of all the elements in the body. The four maṇḍalas that rest in space not only correspond to the maṇḍalas of the four elements in the human body, but they are also the cosmic representations of particular bodily components.

Within different contexts, the Kālacakra tradition draws different correspondences among the four maṇḍalas of the cosmic body and the components of the human body. Here are several illustrations of the ways in which the Kālacakra tradition correlates the four cosmic maṇḍalas with the bodily parts. Table 5.4.a illustrates the identification of the four maṇḍalas with all the bodily parts in terms of their qualitative characteristics. Table 5.4.b demonstrates the correspondences among the four maṇḍalas with the upper parts of the body in terms of their measurements; and table 5.4.c illustrates the identification of the four maṇḍalas with the four bodily cakras, which bear the characteristics of the four elements. From the uppermost maṇḍala downward, each maṇḍala is one hundred thousand leagues smaller in diameter than the one that supports it, and each maṇḍala rests in the center of the one beneath it. In each of the first four maṇḍalas there are two types of underworlds (pātāla), each measuring twenty five thousand leagues in height.

Thus, there are altogether eight underworlds: seven hells and the city of nāgas. The two underworlds contained in the earth-maṇḍala are the City of nāgas and the Gravel Water hell (śarkārāmbhas), one half of the city of nāgas being inhabited by asuras, and the other by nāgas. 34 The two hells located in the water-maṇḍala are the Sandy Water hell (vālukāmbhas) and the Muddy Water hell (paṅkāmbhas). The two hot hells in the fire-maṇḍala are the Intense Smoke hell (tīvradhūmra) and the Fire hell (agni). Lastly, the two cold hells located in the wind-maṇḍala are the Great Severe hell (mahākharavāta) and the Great Darkness hell (mahāndhakāra). As indicated in chapter 3 on syncretism, the Vimalaprabhā's account of the eight underworlds is remarkably similar to that given in the Jaina classic, the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra, which is traditionally ascribed to Umāsvati, a prolific Jaina author of the second century ce who was equally accepted by both Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras. For example, the corresponding hells enumerated in the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra have the following sequence and names: the Jewel-hued (ratna), Pebble-hued (śarkara), Sand-hued (vāluka), Mud-hued (paṅka), Smoke-hued (dhūma), Darkness-hued (tamas), and the Great darkness-hued (mahā-tamas) hells. 35 There are also certain similarities among the hells mentioned in the Vimalaprabhā and those in the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra with regard to the temperature and sequential increase in the size of hells, but not with regard to their shape and specific measurements. 36

Thus, the Vimalaprabhā's classification of the eight types of underworld and its description of their location clearly differ from those in the Abhidharmakośa. 37 It is interesting that in the Vimalaprabhā's account of the configuration of the underworld there is no mention of the Avici hell, even though the Ādibuddhatantra and the Vimalaprabhā make references to Avici in other contexts. 38 So far, I have not encountered an explanation for this omission in any of the commentarial literature on the Kālacakratantra. The only thing the Vimalaprabhā says about hell in general is that it is “a state of an infernal being (nārakatva), which originates from the habitual propensities of the six elements (ṣaḍ-dhātu-vāsanā), and is like a dream. ” 39 But this intepretative principle can also be applied to the other hells and the rest of the universe. It is possible that the author of the Vimalaprabhā, being aware of other Buddhist classifications of hells, writes of Avīci in terms of the broader Buddhist context.

It is also possible that Avīci and some of the other hells described in the Abhidharmakośa and other earlier Buddhist texts are implicitly included here as subcategories of the various hells. Since neither the Vimalaprabhā nor the Kālacakratantra offers a more detailed description of the contents of the hells and the nature of suffering in them, it is difficult to determine with certainty the extent to which the mentioned hells correspond to and differ from the hells described in the Abhidharmakośa and the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra. It is clear, however, that the Kālacakra tradition finds the Jaina classification of hells to be more applicable to its own schematization of the underworld, consisting of the four elemental maṇḍalas than that of the earlier Buddhist traditions. 40 The names of the hells reveal that each pair of hells is physically characterized by the element of the maṇḍala to which it belongs.

This fundamental fourfold classification of the underworld is obviously designed to conform closely to the Kālacakratantra's fourfold classifications of the elemental maṇḍalas in the body of the individual, the four vajras of the individual, the four states of the mind, the four castes, four vajra-families, and the four bodies of the Buddha. The configuration of the underworld, beginning with the city of the nāgas in the earth-maṇḍala and ending with the Great Darkness (mahāndhakāra) hell in the wind-maṇḍala, is structurally similar to the individual's body at death. In the dying process, the earth-element of the individual's body disintegrates first, followed by the respective elements of water, fire, and wind. 41 See figure 5.1. Thus, the Kālacakra tradition departs from the Abhidharmakośa in terms of both the configuration and the measurement of the cosmos. According to the Abhidharmakośa, the cosmos measures 3,610,350 leagues in circumference and 1,203,450 leagues in diameter. 42

The human world is supported by three instead of four maṇḍalas—the golden earth-maṇḍala, the water-maṇḍala, and the windmaṇḍala that rests in space. The golden earth-maṇḍala, which measures 1,203,450 leagues in diameter and 320,000 leagues in height, rests on the water-maṇḍala, which is, in turn, 1,203,450 leagues in diameter and 800,000 leagues in height. The water-maṇḍala rests on the wind-maṇḍala, which is immeasurable in circumference and 1,600,000 leagues in height. 43 The account of the configuration of the surface of the earth-maṇḍala in the Kālacakra tradition also differs from that of the Abhidharmakośa. According to the Kālacakra tradition, on the surface of the earth-maṇḍala there are seven continents (dvīpa), including Great Jambudvīpa (mahā-jambudvīpa) as the seventh.

Furthermore, there are seven mountains in addition to Mt. Meru, which is in the center of the earth-maṇḍala; and there are seven oceans, with the water-maṇḍala as the seventh. 44 The six continents—Candra, Sītābha, Varaparamakuśa, Kimnara, Krauñca, and Raudra—are the lands of enjoyment (bhoga-bhūmi), 45 while the seventh continent, which is the earth-maṇḍala, or the Great Jambudvīpa, is the land of karma (karma-bhūmi), inhabited by humans and animals. On the surface of Great Jambudvīpa, the six oceans—the oceans of wine, fresh water, milk, curd, butter, and honey— surround the six continents. The seventh, the salt ocean, surrounds Great Jambudvīpa, 46 and from the center of Mt. Meru, the salt ocean measures one hundred thousand leagues in all directions. Seventy-two thousand rivers flow into the oceans, 47 and they correspond to the seventy-two thousand nāḍīs in the body. The seven mountains that surround the seven continents in concentric circles are Nīlābha, Mandara, 48 Niṣadha, 49 Maṇikara, Droṇa, Sīta, and the vajramountain, Vādavāgni, which is situated at the edge of the salt ocean and the earth-maṇḍala and beneath the salt ocean. Mt. Meru is at the very center of Great Jambudvīpa, just as the spine is at the center of the body. It is said to have the shape of a bindu and is dark green in the center, due to the nature of the spacemaṇḍala. Meru's four sides have four different colors.

It is blue in the east, red in the south, yellow in the west, and white in the north due to the nature of the elements of wind, fire, earth, and water. In total, it measures one hundred thousand leagues in height. 50 The height of its head is fifty thousand leagues, and its neck and immovable peak are each twenty-five thousand leagues in height. Its upper width is fifty thousand leagues, and its width on the surface of the earth-maṇḍala is sixteen thousand leagues. Meru is the spine and head of the cosmic body; and as such, it is an external representation of the individual's head and spine, expanding from the buttocks up to the shoulders. Accordingly, its measurements correspond to those of the spine and the head of the human body. Table 5.5 illustrates the metrical correspondences bewteen Mt. Meru and the individual's spine and head, as presented in this tantric system. This measurement of Mt. Meru differs from that described in the Abhidharmakośa, in which the height of Mt. Meru is said to be 1,600,000 leagues. Here again, the Kālacakratantra's measurement of Mt. Meru accords with that given in the Jaina commentarial literature on the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra, in which Mt. Meru is said to be one hundred thousand leagues in height, with one thousand leagues being below the surface of the earth. 51

The circle of astrological houses, together with innumerable stellar constellations, revolves day and night around Mt. Meru's summit. In the eight directions of Mt. Meru there are eight planets, just as around the spine there are the sense-faculties and faculties of action. The sun and Mars are on the right; Ketu and Saturn are in the front; the moon and Mercury are on the left; and Venus and Jupiter are on the back. On the top of Mt. Meru there are five peaks that penetrate the earth. In all directions from Brahmā's abode in the lower region of the center of Mt. Meru, there are eight thousand leagues in width. All around Mt. Meru is a mountain range (cakravāḍa), which measures one thousand leagues in breadth. Outside that mountain range, in the cavities in between the four peaks of Mt. Meru that penetrate the earth, there are the alternating discs of the six continents with their oceans and mountains.

Each of the six continents, oceans, and mountains measures roughly 889 leagues in diameter, 52 thus measuring sixteen thousand leagues altogether. Outside all of this, in the eight directions of Mt. Meru, Great Jambudvīpa measures twentyfive thousand leagues. Outside Great Jambudvīpa is a disc of salty water, which measures fifty thousand leagues in all directions from the outer limit of Great Jambudvīpa to the end of the water-maṇḍala. In every direction from Brahmā's place in Meru to the outer limit of the wind-maṇḍala, there are two hundred thousand leagues. 53 In this way, the entire breadth of the cosmos extends up to four hundred thousand leagues in diameter, its size corresponding to the size of the human body measuring four cubits (hasta). However, when one includes the space-maṇḍala in the breadth of the cosmos, then the

body of the cosmos measure five hundred thousand leagues from the top of Mt. Meru up to the end of space. With the reasoning that the cosmos pervades the body of the individual, the human body is said to measure five cubits up to the tips of the hair on the head. This type of arrangement of Great Jambudvīpa is not found in the Abhidharmakośa. The numbers and the concentric layout of the seven continents and seven oceans correspond to those mentioned in the Purāṇas, 54 as do the shape and measurement of Great Jambudvīpa. 55 Although the Kālacakra tradition accepts to a large extent the Purāṇic representation of the configuration of the cosmos, it criticizes the Purāṇic account of the origination of the cosmos.

With regard to the shapes and sizes of Great Jambudvīpa and the salt ocean, the Kālacakra tradition's account corresponds to that of the Jaina cosmology. According to the Tattvārthādhigamasūtra, Ch. 3, v. 9, and its earlier mentioned commentarial literature, Great Jambudvīpa has the shape of a ring with a diameter of one hundred thousand leagues, and it is surrounded by the salt ocean, which is twice as wide as Jambudvīpa. 56 Although the Kālacakratantra's account of the configuration of Great Jambudvīpa seems to be based on that of the Purāṇas, it includes to some degree the model of the four continents found in the Abhidharmakośa and other Buddhist texts. 57 The four continents that are mentioned in the Abhidharmakośa and other earlier Buddhist literature are incorporated into this larger picture of the cosmos as the four islands that are located in the four directions of Great Jambudvīpa. Their arrangement in relation to Mt. Meru as depicted in the Kālacakra literature corresponds to that in the Abhidharmakośa, but the measurements and shapes of the islands in most cases differ. According to the Kālacakra tradition, there are four islands on Great Jambudvīpa.

Each of the four islands is of the nature of one of the four elements—wind, fire, water, and earth. The nature of each of the mentioned elements influences the shapes and colors of the islands. 58 Thus, in the eastern side of Great Jambudvīpa, in front of Mt. Meru, there is the dark blue Pūrvavideha, which is semicircular in form, due to the nature of the wind-maṇḍala. It measures seven thousand leagues. On the south of Great Jambudvīpa, to the right of Mt. Meru, there is Small Jambudvīpa, which is red and triangular in shape, due to the nature of the fire-element. It measures eight thousand leagues. 59 On the north of Great Jambudvīpa, to the left of Mt. Meru, there is the white Uttarakuru, which is circular in shape, due to the nature of the water-maṇḍala. It measures nine thousand leagues. On the west of Great Jambudvīpa, facing the back of Mt. Meru, there is the golden island Godaniya, which is yellow and quadrangular in shape, due to the nature of the earth-element. It measures ten thousand leagues. 60 See figure 5.3.

The formation of the four islands in relation to Mt. Meru and the characteristics of their colors and shapes correspond to the four sides of the individual's body, each of which is characterized by the elemental nature of one of the four bodily maṇḍalas. Table 5.6 demonstrates the way in which the Kālacakra tradition correlates the four islands of Great Jambudvīpa with the four sides of the individual's body. The colors of the four islands correspond to the colors of the four sides of Mt. Meru. Likewise, their colors and formations on Great Jambudvīpa correspond to the four faces of the Buddha Kālacakra in the kālacakra-maṇḍala. The four faces of Kālacakra symbolize the four aspects in which enlightened awareness manifests itself. Thus, the four islands of Great Jambudvīpa and the corresponding sides of the human body are the geographical and anatomical representations of the four aspects of the Buddha's mind. When these phenomenal aspects of the Buddha's mind become purified, they manifest as the four bodies of the Buddha. Great Jambudvīpa looks like a twelve-spoked wheel, for it is divided into twelve sections (khaṇḍa). Each of the sections measures twenty-five thousand leagues.

In the center of the section belonging to the Small Jambudvīpa there is the mountain Kāilāśa, surrounded by snow mountains. Together with the surrounding snow mountains, Kāilāśa occupies one-third of that section. Outside that range there are twelve countries and districts in the twelve subsections of Small Jambudvīpa. 61 In each section of Great Jambudvīpa there is one universal monarch (cakravartin), who turns the Wheel of Dharma in his section. Thus, the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa have twelve universal monarchs, who are likened to twelve suns that dispel the darkness of ignorance by introducing the Buddhist Dharma. They are twelve in number in the same sense that one can speak of “twelve suns” due to the classification of the twelve solar mansions.

Thus, Great Jambudvīpa, together with its twelve sections, is an earthly reflection of the circle of solar mansions and of the twelve-spoked wheel of cyclic existence. Every eighteen hundred human years, the universal monarch enters one section of the earth-maṇḍala, 62 moving progressively from one section to another, from the front to the back of Meru. He establishes his Dharma in each section that has entered the kali-yuga and thereby introduces the kṛta-yuga. Thus, the kali-yuga is always in front of him, and the tretā-yuga is behind him. 63 This belief that at different times, the universal monarch, visiting and teaching Dharma in the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa, sanctifies each of the sections with his presence, is one of reasons that the Kālacakra tradition identifies the twelve sections of the Great Jambudvīpa as the twelve groups of cosmic pilgrimage sites— namely, pīṭhas, upapīṭhas, kṣetras, upakṣetras, chandohas, upachandohas, melāpakas, upamelāpakas, veśmas (pīlavas), upaveśmas (upapīlavas), śmaśānas, upaśmaśānas.

Each of the twelve groups of sacred pilgrimage sites comprises a specific number of sites. The Kālacakra tradition classifies and subdivides the twelve classes of pilgrimage sites in various ways in order to demonstrate the multiple models of interpreting the correspondences between the cosmic body and the human body. One of the Kālacakratantra's goals in outlining the correspondences and identities among the pilgrimage sites and the bodily components of the individual is to demonstrate the pointlessness of visiting the pilgrimage sites, for they are already present within one's own body. Visits to the external pilgrimage sites lead neither to spiritual awakening nor to mundane siddhis. The Vimalaprabhā asserts that the pilgrimage sites such as Jalāndhara and others are mentioned only for the benefit of foolish people (bāla) who wander about the country. 64 This same statement also appears in Nāropā's Vajrapādasārasaṃgraha, XVII, 3b 2. 65 In both cases, it suggests that foolish people, who lack understanding of nonduality, do not see that the places of pilgrimage are omnipresent. The entire cosmos is a pilgrimage site, as is the individual. The Vimalaprabhā states that according to the Paramādibuddhatantra, due to the pervasiveness of the earth-element, the external pilgrimage sites are present also in

Tibet, China, and other countries. According to the abridged Kālacakratantra, they are also present in every city. 66 In this way, the Kālacakra tradition rejects the inherent sacredness of one place or one human being over another. It suggests that all regions of the world and all human bodies are equally sacred. This view of the human body as containing within itself all the pilgrimage sites is not unique to the Kālacakra tradition. It is also found in other anuttara-yoga-tantras and in the literature of the Sahajayāna. For example, the well-known Sahajīya poet, Sarahapāda, affirms in his Dohākoṣa that he has not seen another place of pilgrimage as blissful as his own body. 67 With regard to the individual, the Kālacakra literature identifies the twelve categories of pilgrimage sites with the twelve characteristics of transmigratory existence and enlightened existence.

In terms of conventional reality, the Kālacakra tradition identifies the twelve categories of pilgrimage sites with the twelve links of dependent origination and the twelve signs of the zodiac—starting with spiritual ignorance (avidyā) arising in Capricorn and ending with old age and death (jarā-maraṇa) arising in Sagittarius. In terms of ultimate reality, the Kālacakratantra sees the twelve categories of pilgrimage sites as the symbolic representations of both the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis—which impede the arising of the twelve links of dependent origination and the twelve zodiacs—which are the temporal basis of the twelve links of dependent origination.

This identification of the twelve categories of pilgrimage sites with the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis is equally characteristic of other anuttara-yoga-tantras—specifically, the Cakrasaṃvara and the Hevajra tantras. However, the Kālacakra literature gives a more explicit explanation of this type of identification. The Kālacakra tradition identifies the twelve types of pilgrimage sites with the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis on the ground that throughout the three times, the elements of the Buddha's purified psycho-physical aggregates and sense-bases assume the form of deities. These deities then arrive at and leave from these pilgrimage sites, and due to the prāṇas' flow in the bodily cakras, they arrive at and leave from those cakras. Furthermore, a group of yoginīs who roam the earth for the benefit of sentient beings dwells in each of the eight directions of Mt. Meru, expanding as far as the end of the wind-maṇḍala. These yoginīs also journey in the cosmic maṇḍalas of water, fire, wind, and space, which are the seats of the cosmic cakras, just as the prāṇas move through the cakras of the invidivual's body. Just as the human body has six cakras, so too does the body of the cosmos.

The six cakras of the cosmos are the locations of the cosmic pilgrimage sites. In the center of the summit of Mt. Meru, there is the inner lotus (garbhapadma) of the Bhagavān Kālacakra, which has sixteen petals and constitutes the bliss-cakra (ānandacakra) of the cosmic body. 68 The gnosis-cakra, which has eight spokes, occupies two-thirds of the earth-maṇḍala. The earth-cakra is in one half of the salty ocean, and the water-cakra is in the other half. Likewise, the firecakra is in one half of the fire-maṇḍala, and the wind-cakra is in the other half. The space-cakra is in one half of the wind-maṇḍala. In the space-maṇḍala there are sixteen pilgrimage sites of the śmaśāna type. Tables 5.7.a—h illustrate the specific locations of the pilgrimage sites within the six cosmic and six bodily cakras. They also demonstrate the manner in which the Kālacakra tradition asserts that the cessation of the twelve zodiacs and twelve links of dependent origination is causally related to the transformation of the six cosmic and six bodily cakras into the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis, or the twelve groups of pilgrimage sites. These tables further suggest that in the context of the Kālacakratantra practice, the sequential attainment of the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis is an internal pilgrimage to spiritual awakening.

A tantric adept undertakes an internal pilgrimage by purifying the bodily cakras by means of the six-phased yoga (ṣaḍ-aṅgayoga), which, in turn, purifies the external cakras of his environment. Thus, one may say that in this tantric system, the path of spiritual awakening is metaphorically seen as the ultimate pilgrimage. See tables 5.7.a—h for the correlations among the locations of pilgrimage sites in the cosmos and within the body of the individual. According to the schema given above, each of the twelve categories of pilgrimage sites includes the four pilgrimage sites. Thus, for this tantric tradition, there are altogether forty-eight pilgrimage sites. 69 The number of the subdivisions of the twelve pilgrimage sites and their names as given in the Kālacakra tradition differ from those given in other Buddhist tantric systems. 70 This should not come as a surprise, though, since one encounters various numberings even within each of the mentioned Buddhist tantric systems. The Vimalaprabhā justifies these contradictions as the skillful means of liberating those with sharp mental faculties from grasping onto any physical place. 71 A closer look at the illustrated paradigms of the ways in which the Kālacakra tradition draws the correlations among the external pilgrimage sites and the bodily parts reveals that the diverse numberings of pilgrimage sites are not contradictory or randomly arranged but complementary and carefully designed. They exemplify the multiple ways in which this tantric system delineates the correspondences it sees. As the given correspondences themselves vary, there are different ways of structuring and numbering. The diverse ways of identifying the pilgrimage sites with the components of the individual's body have their specific roles in the different phases of the Kālacakratantra practice. For example, identifying the twelve groups of pilgrimage sites with the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa and with the twelve joints of the individual's body, the Kālacakra tradition attempts to demonstrate a close link among the purifications of the twelve bodily joints and the attainment of the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis and the purification of the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa. A purification of bodily joints implies here a cessation of the ordinary body that is accompanied by afflictive and cognitive obscurations. Therefore, as the tantric adept gradually purifies his bodily joints by means of the Kālacakratantra practice, he also eradicates the obscurations and attains the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis. The identification of the twelve bodily joints with the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa is based on the Kālacakratantra's view of their common relation to the elements of wind, fire, water, and earth. 72 Thus, as one purifies the atomic nature of one's own body, one simultaneously purifies one's own perception of the twelve sections of Great Jambudvīpa as ordinary, physical places. 73 Table 5.8 illustrates the aforementioned correspondences among the twelve pilgrimage sites in the cosmic and individual bodies, which are the phenomenal aspects of the twelve bodhisattva-bhūmis. In some other contexts, the Kālacakra tradition classifies the twelve groups of pilgrimage sites into thirty-six subcategories. It presents thirty-six pilgrimage sites as the dwelling places of thirty-six families of yoginīs, who are the sublimated aspects of thirty-six social classes (j¯ati), thirty-six bodily constituents of the individual, and thirty-six factors of spiritual awakening (bodhi-pākṣika-dharma).

As table 5.9 illustrates, the Kālacakra tradition identifies these thirty-six pilgrimage sites with thirtysix components of the cosmos and the individual. This identification is taught in the “Chapter on Initiation, ” in the context of tantric yogic practices performed during a tantric feast (gaṇa-cakra), in which the thirty-six social classes of the Indian society of that time had to be represented. 74 It exemplifies one of the ways in which this tantric tradition identifies the individual with his social environment. This particular manner of identifying the external and internal pilgrimage sites as the abodes of yoginīs is seen as relevant for the purification of tantric pledges (samaya). It is relevant because the purification of tantric pledges takes place only when the initiate is cognizant of the correspondences given below and applies them in viewing his body and his natural and social environments as nondual and equally sacred. Bringing to mind the sublimated aspects of the participants in a tantric feast and viewing the parts of one's own body and the cosmos as their pure abodes, one purifies one's own vision of the individual, social, and cosmic bodies. By so doing, one transforms one's own body and the cosmos into the sacred pilgrimage sites and brings forth a certain degree of purification. For the specific correlations among the pilgrimage sites and the constituting elements of the cosmos, individual, and Kālacakra-maṇḍala, which a tantric practitioner must know in order to purify his vision and attitude toward his natural environment and toward his own body.

There are several other ways in which the Kālacakra tradition identifies the pilgrimage sites with the individual's body, and these are equally relevant to the aforementioned phase of the Kālacakratantra practice. The following two models are specifically related to the practice of the unification of the tantric pledges (samayamelāpaka), or of the female and male consorts, during tantric sexual yoga performed after a tantric feast. Identifying the sacred pilgrimage sites with the various parts of the male and female body during sexual tantric yoga, a tantric practitioner sanctifies a sexual act, which becomes a kind of blissgenerating pilgrimage. This type of identification also suggests that the bliss and spiritual benefits resulting from a single yogic sexual act equal those resulting from visiting ten kinds of pilgrimage sites.

Table 5.10 illustrates the manner in which the Kālacakra tradition classifies ten pilgrimage sites into two main categories—those corresponding to ten parts of the female body and those corresponding to ten parts of the male body. Whereas table 5.11 demonstrates the way in which each of ten groups of pilgrimage sites is identified with the same male and female bodily parts. All of the aforementioned classifications of the pilgrimage sites illustrate the Kālacakra tradition's premise that on this tantric path to spiritual awakening, one transforms one's own environment, or more precisely, one's own experience of the environment, by transforming one's own physical constituents.

The Three Realms of Cyclic Existence as the Individual

The Kālacakratantra's earlier mentioned principle, which states that “as it is outside so it is within the body, and as it is within the body so it is elsewhere, ” also applies to its view of the interconnectedness of human beings with all other sentient beings. The Kālacakratantra suggests that one should look at the triple world as similar to space and as unitary. 75 The Kālacakra tradition provides a variety of methods for training the mind to perceive all sentient beings as nondual from oneself. These methods are considered to be applicable at any stage of the Kālacakratantra practice, for they reinforce the underlying premise and objective of all Kālacakratantra practices, which are the nonduality of all phenomena and its realization. The Kālacakra tradition points out that all six states of transmigratory existence are already present within every individual. In the Kālacakratantra's view, the origination of a sentient being within a particular state of existence is directly influenced by one or the combination of the three guṇas—sattva, rajas, or tamas. The three guṇas of one's mind are, in turn, the direct result of sentient beings' karma. Thus, the existence as a god is caused by the sattva-guṇa, which, due to wholesome karma, gives rise to the peaceful state of mind. Existence as a denizen of hell is caused by tamas, which due to unwholesome karma, gives rise to the violent state of mind. Existence as an animal is caused by rajas, which, due to the medially unwholesome karma, gives rise to the passionate state of mind. Finally, existence as a human is characterized by the combination of the three guṇas. Similarly, the existences of asuras and pretas are characterized by a combination of two of the three guṇas.

Since human existence is caused by a combination of the three guṇas, the individual's mental states and experiences are often determined by the prevalence of one of the three guṇas. Thus, due to the prevalence of sattva, a person experiences happiness; due to the prevalence of rajas, one experiences suffering; and due the prevalence of tamas, one experiences constant suffering. Because the prevalence of the three guṇas tends to alternate throughout one's lifetime, an ordinary person may experience the mental states that characterize all six states of existence. 76 In this way, the individual who mentally experiences different states of existence in a single lifetime already embodies all six states of existence.

One of the Kālacakratantra's methods of training a tantric practitioner to view all sentient beings as a part of himself is patterned on the fivefold classification of sentient beings, who have five different origins (yoni) of birth. The four different classes of beings who originate from the four respective sources—namely, the earth, wind, water, and womb, and the self-arisen, or apparitional beings (upapāduka), who arise from the element of space—inhabit both the cosmos and the individual. On this tantric path of developing a nondual vision of the world, one should recognize that one's own body, like the body of the cosmos, is the birthplace for diverse sentient beings and is thereby most intimately connected with diverse forms of life. It is a microcosmic representation of the cosmos and its inhabitants. Table 5.12 exemplifies the way in which the Kālacakra tradition correlates the five types of sentient beings in the natural environment with the constituents of the human body and living organisms that inhabit the body. 77

Similarly, to realize the nonduality of oneself and the triple world, one must train oneself to view the three realms of the cosmos—the realms of desire, form, and formlessness—as one's own three vajras— namely, the body, speech, and mind vajras. Only then can one understand that the diverse sentient beings within the three realms of cyclic existence are nondual from one's own mental, verbal, and bodily capacities. Different states of existence are simply the cosmic manifestations of one's own body, speech, and mind, whose sublimated aspects are the body, speech, and mind maṇḍalas of the Kālacakra-maṇḍala. Tables 5.13.a—b illustrate the specific correspondences among the three realms of cyclic existence and the three vajras of the individual and their locations in the bodily cakras, as they are explained in this tantric system. As tables 5.13.a—b demonstrate, the Kālacakra tradition, like other Buddhist systems, classifies the three realms of cyclic existence into thirty-one categories. According to this tantric system, from among these thirty-one categories of cyclic existence, four belong to the formless realm, sixteen to the realm of form, and eleven to the desire-realm. Here again, one encounters some departure from the Abhidharmakośa, according to which, the realm of form contains seventeen types of existence, and the desirerealm is comprised of ten. The Kālacakra tradition omits the class of Sudṛśa gods of the realm-form and adds asuras as the eleventh class of beings belonging to the desire-realm. Likewise, the names of the heavens of the realms of form and formlessness differ from those in the Abhidharmakośa and accord with some of the names of heavens listed in the Jaina Tattvārthādhigamasūtra, Ch. 4, v. 20. According to the Kālacakra tradition, at the top of the cosmos, above the thirty one types of cyclic existence, in the crest of Mt. Meru's peak, abides Kālacakra, the indestructible Vajrakāya. He is accompanied by all the Buddhas and surrounded by the guardians of the ten directions. 78 The location of the three realms in the body of the cosmos corresponds to their location in the body of the individual.

Below Meru's uṣṇīṣa, in the area of its head, there are the four divisions of Saudharmakalpa, a heavenly abode of the formless realm. 79 Those who have developed a meditative concentration (samādhi) on the four types of the space-kṛtsna are born in the formless realm. The four heavens of the form-realm are sequentially located in the regions of Meru's lalāṭa and nose, in the area beneath the nose that extends up to the chin, and in the region of Meru's throat. One is born within one of the four divisions of the form-realm by developing a meditative concentration on the respective wind, fire, water, and earth kṛtsnas and by the power of ethical discipline (śīla). The desirerealm extends from the bottom of Meru's throat to the bottom of the wind-maṇḍala. Sentient beings are born as gods of the desire-realm due to the power of generosity (dāna) and due to the recitation of mantras.

The remaining types of existence in the realm of desire are those of asuras, humans, animals, pretas, and denizens of hells. The existence of asuras comes about by the power of generosity. Human existence is due to the power of one's wholesome and unwholesome actions. Animal existence results from lesser sins. The existence of pretas is due to the power of middling sins, and the existence of the denizens of hell comes about through the power of the greatest sins. Tables 5.14.a—b give a schematic presentation of the life spans of the sentient beings in the cyclic existence, as taught in the Kālacakra tradition. 80 According to this tantric tradition, the life spans of all sentient beings are related to and measured by the number of their breaths. Within the six states of existence, breaths of the different types of sentient beings have different durations.

For example, the duration of one breath in the human realm is one solar day for an insect, a duration of thirty human breaths is one breath for a preta, one human year is one breath of the gods in the Akaniṣṭha heaven, and a hundred years in the human realm is one breath of the gods in the formless realm. Thus, just as the cosmos is perceived and experienced differently by different sentient beings—relative to their karma and state of existence—so too is time a relative phenomenon, experienced differently by different sentient beings. The Kālacakra tradition considers the age of one hundred years as the full life span of the individual, which can decrease or increase in accordance with the individual's own karma. It increases for yogīs and ascetics who, by the power of their yoga and meditative concentration, extend the duration of a single breath for up to one ghaṭikā; and it decreases for evil people due to the power of their sins. Thus, the duration of one's life is directly related to the duration and number of one's breaths, which, in turn, is directly related to one's mental states. As the mind becomes more afflicted and agitated, one's breathing becomes faster, breaths become shorter, and thereby one's life becomes shorter. It is in the form of the breaths, minutes (pāṇipalas), ghaṭikās, and solar days that death takes its course in the body. As these measures of time gradually increase within the right and left nāḍīs, death advances in the body, until the prāṇa finally leaves the nāḍīs, which dissolve and cause a bodily disintegration. The notion of the full human life span being one hundred years goes back to the early Brāhmaṇic period. In support of this notion, the Vimalaprabhā cites a line from the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, II. 17. 4. 19, which states that a person (puruṣa) has a life span of a hundred years. 81 The Vimalaprabhā interprets this statement in terms of both its provisional and definitive meanings. In terms of a provisional meaning, a person has a life span of a hundred years, due to the increase of the human life span during the kṛta-yuga. In terms of the definitive meaning, the word “person” (puruṣa) designates here every solar day and every year. This implies that with regard to the individual, there are one hundred solar days, and with regard to the cosmos, there are one hundred years. Thus, one year in the individual's environment corresponds to one solar day in the body of the individual, in accordance with the number of the individual's breaths. On the grounds that the individual takes twenty-one thousand and six hundred breaths each solar day, two hundred such solar days in a human body are said to equal 4,320,000 years in the environment, which make up four cosmic yugas. 82

Thus, with each round of 4,320,000 breaths, which the individual takes in the course of two hundred solar days, a cycle of four cosmic yugas takes place in the body. In this way, all temporal and physical changes that occur in the body of the cosmos have already taken place in the body of the individual. A goal of the Kālacakratantra practice is to transmute these phenomenal bodies of the cosmos and the individual into the transcendent body of the Buddha Kālacakra, into the Vajrasattva, who is the indivisible unity of the three realms of cyclic existence. The process of their transmutation entails their generation in the form of the Kālacakra-maṇḍala by means of the stage of generation practice and their dissolution by means of the stage of completion practice. At the time of the transformation of the individual's body into the transcendent body of Kālacakra, the constituents of the phenomenal body manifest as the constituents of spiritual awakening. Thus, certain bodily components—bodily hair, skin, flesh, blood, water, bones, marrows, and the like—manifest as the bodhisattva-bhūmis. The four great elements of the ordinary body—earth, water, fire, and wind—manifest as the four brahma-vihāras—loving kindness (maitrī), compassion (karuṇā), sympathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekṣā). The five ordinary pshycho-physical aggregates, accompanied by afflictive and cognitive obscurations, manifest as the five types of unobscured psycho-physical aggregates, or the five types of gnosis—the mirror-like gnosis (adarśajñāna), the gnosis of equality (samatā-jñ¯ana), the discriminating gnosis (pratyavekṣana-jñāna), the accomplishing gnosis (kṛtyānuṣṭhāna-jñāna), and the gnosis of the sphere of reality (dharma-dhātujñāna). When the bodily constituents become free of obscurations and atomic matter, they manifest as the empty form. Although the empty form is endowed with aspects of fire, earth, water, and the like, due to its immateriality, it is neither a fire, nor is it solid or liquid. Likewise, although appearing with various colors, it has no color. It is said to appear like an illusory city. 83 The Kālacakratantra states that although the empty form is endowed with all aspects (sarvākāra), “foolish people are unable to see it anywhere, due to the power of their mental obscurations, which are sustained by the flow of the prāṇas in the right and left nāḍīs. ” 84 Thus, even though the entire universe is ultimately the omnipresent, empty form, it is not perceived as such by those whose perception is obscured by their materiality.

The Wheel of Time, the Individual, and the Wheel of Time as the Individual