Marxism and Moksha

By Peter Wilberg 2008

Introduction

The overall aim of this essay is to present a new trans-ethnic, trans-national, trans-sectarian, trans-Hindu and trans-Buddhist understanding of religious Tantrism and Advaitic philosophy - showing them to be complementary to secular European Marxism and Dialectical philosophy respectively. To begin with I contrast the opposing secular and religious concepts of ‘liberation’ signified by the terms ‘Marxism’ and ‘Moksha’, respectively - subjecting this apparently irreconcilable dualism to both philosophical and historical deconstruction, and showing the common understandings uniting Advaita and Dialectics. I then move on to stating the central claim of the essay, namely that the true locus of ‘Moksha’ - understood as both spiritual and political ‘liberation’ - is neither the body politic or community nor the individual in isolation but rather a ‘third realm’ identified by the Jewish thinker Martin Buber – namely that of immediate human relations between individuals in both social and communal contexts.

It is in this context that I argue that the essence of the Indian religious philosophy of Advaita or ‘non-duality’ is nothing but relationality as such – both between human beings, and between human beings and higher beings. However in order to achieve a revolutionary religious transformation of relations between human beings (as well as between human beings, higher beings and God) I emphasise the importance of recognising differences or ‘asymmetries’ in levels of human awareness – yet without making the classic mistake of identifying these asymmetries with differences of gender, race, caste, class or culture. With such differences in mind however, the essay traces the subversive, sex-political dimension of religious ‘Shaktism’ and ‘Tantrism’ in colonial India, drawing intensively on Hugh Urban’s research into the relation between British and Indian representations of their central symbol – the feminine goddess Kali. This leads into a discussion of more recent expressions of the sexual, political and sex-political dimensions of so-called ‘left’ and ‘right-hand’ traditions of Tantra in Europe.

Finally I draw on the work of Victor and Victoria Trimondi to show the historically misogynistic character of Tibetan Buddhism and Buddhist Tantrism in contrast to (a) the primordial Indian religious traditions of Shaktism, and (b) the synthesis of Tantrism in 'Kashmir Shaivism'.

In conclusion, I point to the future role allotted in the Buddhist Kalachakra Tantra to a figure called the 'Rudra Chakrin' – Rudra being, paradoxically, the Vedic god equivalent to Shiva, both ‘Rudra’ (Sanskrit) and ‘Civa’ (Tamil) meaning ‘red’ or ‘reddening’ - and Chakrin ('wheel turner') being a term synonymous with 'revolutionary'. The paradox is one of Buddhism itself raising the Red Banner of a Hindu god – Rudra - as that god empowered to turn the wheel of spiritual-political revolution for a coming age. However this ‘red revolution’ or ‘inner revolution’ as Robert Thurman (America’s chief advocate of Tibetan Buddhism) conceives it, turns out to present only an amalgam of the weakest and least ‘red-blooded’ of liberal policies as its political platform for universal liberation or Moksha - policies totally empty of any Marxist understanding of capitalist economics, and sanctified and supplemented instead merely by the traditional Buddhist principle of “emptiness of self” and the advocacy of a new Tibetan-style monasticism.

In the first of three appendices, I cite from the Trimondis’ critique of the idealised ‘spiritual’ image of social life in pre-Communist Tibet - an image still fostered throughout Europe and the West. In the second appendix I cite from Justin Whitaker’s summary of the views of Marxist psychologist Slavoj Žižek on Western Buddhism. In the final appendix I cite a brief account of my own of the Virashaiva sect of Southern India, showing it to be an early example of a social-spiritual liberationary movement based on a tantric stream of heterodox 'Counter-Hinduism' long present within 'Hinduism' itself.

It is hoped that the essay as a whole may make some small contribution to a deeper and more thoughtful exploration of the secular-religious divide in India today.

Marxism and Moksha

‘Marxism’ and ‘Moksha’. At first, the disparity signified by the two terms seems too great, the distance between them too daunting, the contradiction or ‘duality’ they signify too clearly defined to even warrant any deeper consideration - leaving us to accept without questioning for example, the unavoidability of the continuing political opposition in India between parties with a secular Marxist orientation and those based on a Hindu religious ideology. So let us begin by precisely setting out the distance and disparity between Marxism and its so-called ‘materialism’ on the one hand, and the spiritual-religious concepts of ‘Moksha’ or ‘Mukti’ on the other - doing so in the most seemingly irreconcilable or ‘dualistic’ of terms:

1. Marxism: a global secular, historical, atheistic and ‘worldly’ philosophy rooted in European thought and offering the prospect of liberation (the meaning of ‘Moksha’) and release from suffering only through a social revolution founded on the recognition and overcoming of real economic contradictions or ‘dualities’ in the world of work, in particular the unfreedom of the labourer in class societies, an unfreedom deriving from that most decisive of all forms of alienation of the human being from the essence of his own being – what Marx called the “alienation of labour”. For it this alienation, which, according to Marx, leaves the human being feeling most human only in the exercise of his most animal capacities (eating, drinking, fucking and herd-like ‘partying’ etc) and most animal in his most essentially human capacities – the God-like capacity for creative activity or ‘labour’. In slave societies, the labourer as such is a mere commodity to be bought, sold and disposed of in any way by his master. In capitalism it is the individual’s labour power and time - no less separable in essence from both their body and mind, that suffer the same fate - becoming a commodity to be sold and disposed of in any way dictated by capitalist owners of the means of production and their master, the Market.

The new modes of mass production developed with capitalism leave the individual’s most individual creative potentials either unfulfilled or exploited – both in conditions of unemployment and even, if not above all in conditions of so-called ‘full employment’. The two principle Mantra of Marxism can be spelled out as follows. In class societies life as creative sensuous activity is reduced to ‘earning a living’ – to earning a life – through a type of ‘work’. Work in turn - and in its very essence is prostitution – the enforced economic prostitution of both body and mind on the part by the labourer in return for a more or less limited freedom to buy back its products in the form of commodities.

As Marx himself defined it:

“What then constitutes the alienation of labour? First, the fact that labour is external to the worker, i.e., it does not belong to his essential being; that in his work therefore, he does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He is at home when he is not working and when he is working he is not at home. His labour is therefore not voluntary but coerced; it is forced labour. It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it. Its alien character emerges clearly in the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists, labour is shunned like the plague. External labour, labour in which man alienates himself, is a labour of self-sacrifice, of mortification.”

This ‘alienation’ or ‘estrangement’ of labour, as Marx called it, “makes man’s life activity, his essential being, a mere means to his existence.” “Life itself appears only as a means to life”.

No authentic state of ‘spiritual freedom’ (‘Moksha’) can be attained without the recognition of this, most fundamental economic form of spiritual ‘bondage’ – the economic yoke imposed on human labour. The idea of attaining such spiritual freedom merely through ‘yoga’ – a word whose root meaning is ‘yoke’, seems indeed, from this point of view, a mere cynical joke, compounded in our current era by the global commodification of yogic philosophies and practices themselves, which are marketed as a palliative for ‘stress’ - the individual’s sense of alienation - whilst denying its foundation in economic exploitation. Such a commodified ‘yoga’ may serve to ameliorate, but thereby also serves to shore up the continuing yoke of alienated labour imposed by global capitalism, a yoke imposed not just on the free spiritual life of the individual but on their free bodily activity – the latter finding expression only through the compensatory euphoria of drunkenness or violence. This yoke can only be overcome through a communist social revolution.

2. Moksha / Mukti: the central spiritual aim of traditional, communalistic ethnic-Hindu religious philosophies rooted in India, yet conceived of, in contrast to Marxism, as an ultimate state of individual ‘liberation’ (Moksha) or ‘release’ (Mutki) from the entirety of worldly existence and the trans-historical cycle of death and rebirth. Moksha or liberation in this spiritual rather than social sense is seen as rooted in a recognition of the fundamental unreality (Maya) of all apparent contradictions or ‘dualities’ of both thought and lived experience. It is attainable only through yoking oneself to specific mental and bodily disciplines or ‘yogas’ under the guidance of a guru, whereby the individual comes to a direct and sustained experience of the fundamental non-duality, non-separation or ‘non-alienation’ of the self from the divine - understood as a transcendent yet all-pervasive and universal reality immanent in all beings and manifesting itself at all times and in all epochs and life episodes – including whole historic epochs of conflict and conflagration, war and destruction, as well as individual lifetimes or episodes of suffering and violence.

Having thus set out in summary brevity, but I hope also sufficiently, the seemingly clear contradictions or ‘duality’ dividing and mutually opposing the secular and religious world-views condensed by the terms ‘Marxism’ and ‘Moksha’ respectively, the question immediately raises itself as to how this very duality is or might be understood within and from the perspective of each of these world-views. The question is a significant one precisely because both world-views are, in the most specific of ways, philosophies which, each in their own way, give immense prominence to the nature and relation of ‘duality’ and ‘non-duality’. In the Marxist tradition, derived from Hegel, the key signifier of this thematic is the Greek-based term ‘dialectics’, and the notion of an immanent movement and evolution not only of thought but of reality itself, which takes the form of contradictions, antitheses or dualities progressively unfolding from one another in historical life through the emergence of a transcendent ‘third’ term – one which is no mere synthesis’ of thesis and antithesis - for it no sooner arises than it becomes the first or ‘thetic’ terms of a new antithetical duality. In the Indian tradition it is the Sanskrit-based concepts of ‘dvaita’ (duality) and its counterpart (‘a-dvaita’ or non-duality) and the duality and/or non-duality of both that is the central, albeit de-historicised issue. One is reminded here of both Hegel, with his dialectical principle of the ‘identity of non-identity and difference’, and its advatic equivalent – the non-duality of duality and non-duality. Before we stray too soon in the one-sided direction of either a dehistoricised or over-detailed historical analysis of both Dialectics and Advaita, let us first of all simply take note of their clearly apparent similarity (or ‘similarity-in-difference’) and the way in which, in and of itself, this implies a dimension of hidden ‘unity’ or ‘non-duality’ between ‘Marxism and ‘Moksha’ themselves, an interstice of European and Indian thought that opens up a rich but still almost wholly unexplored vein of exploration - both philosophical and historical, religious and political. To begin with however, let us stick with the dimension of opposition and duality which the summary descriptions of the two world-views were intended to highlight - and simply tabulate, from the very words deployed in these definitions, some of the central linguistic dyads, dichotomies or dualisms they invoke:

MARXISM

MOKSHA

European

Social

Secular

Atheistic

Modernistic

Historical

Universalistic

Communistic

Sees contradictions as real

Liberation through social revolution

Indian

Individual

Spiritual

Theistic

Pre-Modern

Trans-Historical

Hindu Ethnic

Communalistic

Sees contradiction as illusions of duality

Liberation through individual consciousness

Paradoxically of course, the last dichotomy shows that Marxism is also and itself essentially a philosophy of liberation or ‘Moksha’. The deeper purpose of this tabulation of antonyms however, is that it allows us to introduce a ‘third term’ besides the duality of Marxism and Moksha, but one of no little significance in relation to them both: ‘post-modernism’. For those unfamiliar with the origins of this term, it is rooted in model of language – both language as such and specific languages or ‘modes of discourse’ (not least philosophical, theological, scientific and theoretical languages) as more or less selective structures of mutually defining or opposing terms such as ‘true’ and ‘false’, ‘black’ and ‘white’, ‘higher’ and ‘lower’, ‘good’ and ‘evil’, ‘positive’ and ‘negative’, ‘creative’ and ‘destructive’, ‘phenomenon’ and ‘noumenon’, ‘transcendent’ and ‘immanent’. Such dichotomies or dualisms, though they take the form of binary pairs or verbal distinctions need not necessarily be understood as contradictory opposites or antonyms. The specific theoretical language or ‘discourse’ of Marxism itself for example, though it revolves around a basic set of binary verbal distinctions or dichotomies such as ‘use value and exchange value’, ‘base and superstructure’, ‘man and nature’, ‘idealism’ and ‘materialism’, ‘scientific’ and ‘utopian’ socialism etc., understands each term as inseparable from its other - whilst the Marxist theoretical framework as a whole is precisely intended to serve the purpose of exploring the historical evolution and transformations resulting from their inner ‘dialectical’ relation. It is to this purpose that we owe Marx’s historic analysis of the relation between the use-value and exchange value of a commodity. This begins on the level of simple barter of commodities, progresses through the simple market relation defined by the triadic formula ‘C-M-C’ (commodities being sold for money in order to purchase other commodities) and ends up historically with capitalist economies based on the formula ‘M-C-M’ – money invested in commodities in order to obtain a monetary return. At the same time the analysis of the commodity form in its dual aspect of use- and exchange-value, shows how the former use-value of things is progressively subsumed by and made secondary to their exchange value or ‘market value’. Conversely ‘exchange value’ itself begins as the mere abstract idea of ‘equivalence’ between particular quantities of commodities with quite different material qualities and uses. Yet this abstract idea then itself takes on material form in the form of money - firstly in the form of precious metals such as silver or gold which retain their own use-value, and later in the form of mere materialized signifiers of exchange-value - ‘paper money’ with no inherent use-value of its own. With the increasing dominance of finance capital made possible through technologies of instantaneous global investments and divestments, exchange-value once again loses all material form and becomes a ‘mercurial’ quantity in the metaphorical sense – one whose sole reality is an ever-ex-changing ‘virtual’ reality flickering on the screens of stock analysts and traders in the world’s great stock exchanges. The new formula of the inner relation of use-value in the form of the Commodity and exchange-value in the form of Money is now ‘M-M-M’ – for with the dominance of finance capital, exchange value in the form of monetary currencies and stock values itself become the principal Commodity, one whose sole use-value is its own increase and accumulation through financial speculation.

The deep historical dynamics revealed by such dialectical analyses however, is precisely the one which ‘post-modernism’ seeks to deny, arguing instead that it is not history but language as such – those very sets of binary constructs which make up the ‘discourse structure’ of particular theoretical models, world-views or philosophies – which themselves constitute or construct the very realities (including historical realities) that they claim to reveal or represent. The work of post-modern thinking then, is reduced to one of identifying and ‘de-constructing’ the binary constructs of any theoretical model or praxis - showing how they construct the very ‘objects’ whose true nature they claim to explain. Derrida in particular is responsible for this trend in thinking, one in which he particularly emphasised the way in which the language of any given world-view or theory tended to privilege one term or pole of a binary pair over its other – either by not naming its ‘other’ at all, or by treating it as less fundamental, real or essential. An example from Marxist theory would be its base/superstructure distinction – and the supposedly more fundamental and determining role allotted by Marx to the economic ‘base’ of society as against its cultural and political ‘superstructure’.

Dialectics, Advaita and Deconstructionism

Applied to undialectical modes of religious, philosophical and scientific discourse however, the deconstructionist approach characteristic of post-modernism seems clearly vindicated. For it is only too clear how religious world-outlooks tend to invariably privilege or ‘valorise’ one pole of any given binary construct over another. Thus in the context of Judaeo-Christian religious discourse ‘good’ is clearly ‘better’ than ‘evil’, ‘God’ is clearly ‘higher’ than Man and Nature, the Judaeo-Christian God ‘superior’ to all previous gods (now spelled with a de-Romanised small ‘g’) and its theology ‘truer’ than all pre-Christian ones. Such a relatively simple (which is not to say simplistic) deconstruction of the languages of the Abrahamic religions (Islam included) is in no way as easy to apply to those of Asia and the East - Hinduism, Taoism and Buddhism in particular. For though they have even clearer exposition of their own understanding of divinity as an ultimate or absolute reality, in the theological philosophies or ‘theosophies’ of all the ‘Dharmic’ as opposed to Abrahamic faiths we also find a more or less explicit counterpart to the Dialectical thinking so central to Marxism – hence what has come to be called Taoist or Buddhist ‘dialectics’, itself historically rooted in the Indian philosophy of ‘Advaita’ or ‘non-duality’. Recognising this, we can begin to understand the very dichotomy or duality which is the subject of this work - ‘Marxism’ and ‘Moksha’ – on a deeper level, one which hinges on the meaning and relation not of two but of three distinct terms – ‘Dialectics’, ‘Advaita’ and post-modernist ‘Deconstructionism’. The principal accusation leveled at the latter is one of totally relativising the truth of the different terms and distinctions that characterise different secular or religious world-views, since each not only construes but linguistically constructs the very concepts of truth or reality that it claims to singularly most truly represent. What this so-called ‘post-modern’ linguistic paradigm fails, paradoxically to take any historic account of is the way in which ‘pre-modern’ religious philosophies, Eastern and Western, were the first to acknowledge the formative power of language - whether as the Graeco-Christian concept of the ‘Logos’ or ‘Word’ become Flesh and the corresponding understanding of Nature as God’s living speech, or both the Kabbalistic and Tantric theologies of a primordial alphabetic matrix of world-creation (Gematria/Matrika), one that Jews saw signs of in the Hebrew alphabet and Hindus in that of Sanskrit.

It is from the Greek word logos and its root verb legein (to gather) that the terms ‘logic’ and ‘dialectic’ itself derive, not to mention the ‘-logies’ such as biology and psychology and common words as ‘analogy’, ‘legend’, intelligence, intellect etc. Indeed the abstractly theoretical term ‘dialectics’ can be understood in a more originary way through the word itself, and in particular through the common word ‘dialogue’, for this is a word whose root meaning has to do precisely with what is mediated ‘through the word’ (dia-logos). The word ‘dialogue’ however leads us into the realm of living human relations rather than abstract conceptual ones alone – what the Jewish social and religious thinker Martin Buber called the realm of the ‘Between’ or ‘Inter-Human’ (das Zwischenmenshliches). And what is mediated ‘through the word’, whether conceived dialectically or lived dialogically, can be understood as nothing less than relationality as such. Relationality in turn can be understood as the very essence, both of ‘Dialectics’ and ‘Advaita’. For whether we posit a relation of duality or non-duality between any two or more elements, or even a relation of duality and non-duality, we still imply an initial set of elements whose relation is to be determined or posited as ‘dual’, ‘non-dual’, neither or both. Yet what if relationality as such is more primordial than any elements we seek to place in relation, whether a relation of separation or unity, duality or non-duality? What if relationality is what first distinguishes and unites the poles of any relation? What if, to use the expression of philosopher and physicist Michael Kosok, all identifiable or distinguishable elements of experience are not elements ‘in’ relation but of relation? In contrast, to simply posit or oppose a relation of duality or non-duality between any two things is to imply that they are not already dual elements or poles of a singular non-dual relation – like two sides of a coin. In this way we miss the essential point that ‘duality’ and ‘non-duality’ are themselves but dual aspects of relationality as such.

Relationality lies at the very core, not just of Dialectics but of Marxist theory as a whole, in a way which makes it entirely misleading in principle to think of it as a form of economic determinism, or even to describe it as ‘social-ist’ as opposed to individualistic. For one thing Marx’s very definition of ‘communism’ was a stateless community in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” - and not the other way round as so many, not having read this definition in The Communist Manifesto itself, all too readily assume. More importantly, the primary aim of Marx’s work from its earliest beginnings lay not in expounding some ‘economistic’ theory of society or individual consciousness, but rather in exposing how, in societies founded solely on economic property relations, relations between human beings are shaped by and ultimately reduced to relations between things – commodities. Similarly, as the Jewish thinker Martin Buber put it, the ‘I-It’ relation, a relation to some ‘thing’ or ‘It’ - or to the human being perceived as a thing or ‘It’ - replaces an authentic relation of beings, an ‘I-Thou’ relation. The relation of human beings to nature too, takes the form of an ‘I-It’ relation, thus reducing both human beings and nature to what Heidegger called a mere ‘standing reserve’ of exploitable natural or human ‘resources’.

“In our age the I-It relation, gigantically swollen, has usurped, practically uncontested, the mastery and the rule. The ‘I’ of this relation, an ‘I’ that possesses all, makes all, succeeds with all, that is unable to say Thou, unable to meet a being essentially, is lord of the hour.”

Martin Buber

Revolution, Relation and ‘The Third Realm’

So what can be done? If we wish to help bring about a revolutionary transformation of the world do we militate or meditate? Do we yoke ourselves to a socialist political ideology or to a spiritual guru, with neither or with both? Do we identify with modern, universalistic and revolutionary movements aimed at the realization of ‘communism’ or identify with a pre-modern, regionally-centred, ethnically-rooted and communalistic religion focused on individual self-realisation?

It was the profound insight of Martin Buber that the true locus of radical change or ‘revolution’ – the attainment of worldwide human liberation or ‘Moksha’ - lies neither in the realm of society or community nor that of the individual, that it can be achieved neither through social revolutionary movements - least of all nationalistic ones - nor through the security of self-centred religious or spiritual communities. Instead the decisive locus of revolutionary change is a third realm - one beyond the realm of the social or communal on the one hand, and the realm of individual consciousness on the other. The ‘third realm’ is the realm of relationality as such - of immediate human relations between individuals.

“The individual is a fact of existence in so far as he steps into a living relation with other individuals. The aggregate is a fact of existence in so far as it is built up of living units of relation.”

Martin Buber

The starting point for a worldwide revolutionary transformation of human relations can only lie in immediate human relations themselves – in those very “units of relation” that shape the reality of both individuals and the social, economic or communal groups and institutions they belong to. ‘Human relations’ on a group, institutional, social, economic, communal, national, international and worldwide global scale can only be changed by changing the way in which individuals relate to one another as individuals within families and communities, groups and institutions.

No spiritual or political initiatives and activities can bring about any fundamental or ‘revolutionary’ changes in human relations unless those activities and initiatives are the expression of a revolutionary spiritual transformation of human relations between the very people who initiate them.

Raising each individual’s awareness of the real economic, political and cultural contradictions that stand in the way of liberation or Moksha is the vital task of Marxism. Raising each individual’s awareness to a higher plane per se – in a way that in and of itself can free individual consciousness from the yoke of these real contradictions is the task of traditional or classical ‘yoga’. Learning to guard and embody this free liberated state of awareness (Svatantrya) in our living relations with other individuals in our life world is the task of a revolutionary ‘New Yoga’ – understood as a yoga of aware and transformative relating – a yoga of ‘Relational Revolution’. Yet the sad but persistent dilemma besetting those on a traditional spiritual or political path is that the deeper or broader their spiritual or political awareness becomes, the more isolated they may feel - for example by finding relationships with those with different world-views or with a shallower or narrower awareness uncomfortably confining. As a result of this dilemma they may either retreat into deliberate isolation or else seek the superficial comfort of a group or community that merely shares the ideological or religious symbols of a ‘higher’ awareness. Deep or authentic community on the other hand can only arise out of living “units of relation” – multiple deep one-to-one relationships between its members. Such a community is quite different in nature from one that substitutes for such relationships – let alone one that suppresses them in the service of an overriding allegiance to a group ideology. That is why, in the absence of deep relationships and communion between specific individuals within a community, even such things as sharing in communal events - whether political gatherings or demonstrations or religious festivals and celebrations – may even end up leaving the individual with an intensified sense of isolation. Hence neither hermetic retreat, ‘being alone together’ in a symbolic community, nor resignation to what is felt as the compromise of ‘ordinary relationships’ may suffice to overcome the aware individual’s sense of social isolation.

For the more politically-oriented individual this isolation may actually lead them away from aware relating to others and be replaced instead by a militant hostility towards others – for example in the form of individuals, groups or communities with other values or convictions, ethnic origins, class or colour. For the more spiritually oriented individual the same intensified isolation may lead to ever greater identification with their own divine Self – yet at the exclusion of aware relations to the living human Others in their lives. And whilst this can lead to the experience of evermore exalted and higher states of divine-spiritual Self-awareness, the individual’s capacity to embody this awareness in deepened relations with a human Other diminishes. The result is a vicious circle in which an ever-greater spiritual ‘realisation’ of Self through relationship with God leads to an ever-diminished spiritual relationship to human Others. One very central reason for such dilemmas and vicious circles of isolation is a failure to fully accept and finds ways of responding to unavoidable asymmetries in adult-to-adult or peer relationships - differences in maturational levels of awareness. In peer relationships these differences may be felt by the more aware as isolating in themselves - or lead to them to act or be perceived as distant or haughty by the less aware. Parents or teachers, on the other hand, accept awareness asymmetries in relationships from the very start. They do not expect their children or their students to be cognizant or aware of all that they are aware. They not only ‘make allowances’ for their childrens’ or students’ lack of awareness, but relate to them with the aware intent to gently educate’ and ‘draw out’ a greater awareness (e-ducare). This acceptance of asymmetry in the parent-child and teacher-student relationship comes to a different type of expression in the guru-disciple relation. For this is a relation in which the Guru unites the role of teacher with that of spiritual parent to another - albeit often younger - adult. The aim of the Guru in fulfilling this role however, is precisely to offer a model to the disciple of how they themselves can relate to other adults on a basis of total equality and respect - whilst at the same time not only making allowances for asymmetries of awareness (still less accommodating to them) but intentionally and actively using ‘skilful means’ to overcome them and heighten the awareness of the other. This requires a deep capacity on the part of the Guru to meditate the other – that is to say to meditate and identify with a specific human other as well as with the divine self within them. Only in this way can the disciple be led to an experience of their own divine self - whilst at the same time learning from their Guru by what profound means and modes of meditative and aware relating they too can find relational fulfillment through spiritually teaching and parenting other adults.

Yet just as a child has only an inkling of the adult world of the parent, so the disciple has only an inkling of the larger world of awareness of the guru. And just as the child learns about the world of their parent in a way that is primarily relational - from the ways their parents relate to them from that world - so too, does the disciple learn about the guru’s larger world from the latter’s way of relating to them from that world.

What I have called ‘The Awareness Principle’ and ‘The Practice of Awareness’ constitute the grounding principle and practices of a ‘New Yoga’ – ‘The New Yoga of Awareness’. Together they show how the false dualism of hermetic isolation and communal belonging can be overcome through practices of aware asymmetric relating. The Practice of Awareness in asymmetric human relations is based on The Awareness Principle itself. This ‘principle’ of awareness distinguishes all experiential contents of consciousness or awareness from consciousness as such or ‘pure awareness’. The practice of this ‘Awareness Principle’ has to do with ceasing to identify with contents of consciousness - with anything we experience or are aware of - and identifying with the pure awareness of these contents. A central way of Practicing the The Awareness Principle is to recognise that awareness of asymmetry – of the limitations, superficiality, lower level or narrower focus of another person’s awareness - is nothing that need be felt or feared as isolating. Why? Because the very awareness of asymmetry is not itself anything limited, lowered, or rendered narrow or superficial by that asymmetry. The fear or discomfort of feeling one’s own awareness confined within the narrower horizons of another comes from (a) fear or failure to be aware of asymmetry - to fully recognise, accept and make allowances for the limits or confines of another’s awareness (b) failure to identify with the pure awareness of those limits or confines - an awareness that is not itself limited or confined by them, and (c) lack of the awareness and skills necessary to successfully relate to the other from a place of higher awareness – rather than feeling or being confined by the lower awareness of the other. If asymmetries of awareness are not responded to through aware relating, those with higher awareness may end up just avoiding social contacts, situations and relationships altogether out of fear of feeling confined and isolated by them. Without the meditative means to engage in aware relating in asymmetric situations, self-isolation is chosen as the safer alternative to social isolation.

Unavoidable asymmetries of awareness between individuals however should not be identified with differences of gender, class, race or caste. The belief that women and/or people of a different race or lower social caste or class are innately inferior in awareness has been the curse running through countless religions and spiritual traditions, Eastern and Western. It must be emphasised too, that awareness and acceptance of asymmetry in adult relationships, and the practice of aware relating in response to it, is not just a way of accommodating to the limits or lesser awareness of others. On the contrary, it is what allows the highly individual nature of the limitations evident in another person’s awareness to become a source of deep interest, meditation, learning and insight rather than a cause for boredom or accommodation, restlessness or a sense of innate superiority. For the aware acceptance of asymmetries in relationships also turns all social situations into opportunities to recognise what I term ‘reverse asymmetry’. By this I mean the opportunity to appreciate and learn from the unique individual qualities of awareness embodied or expressed even by persons with a ‘quantitatively’ lower level of awareness. The principle of reverse asymmetry gives expression to a notable autobiographical remark made by Martin Buber. Here he describes the enduring life inclination he felt impelled to embody, one which recognises both the transformative power of aware relating and the ‘reverse asymmetry’ or reciprocity of relational transformation. Thus, speaking of his central life inclination Buber wrote:

“It was just a certain inclination to meet people. And as far as possible, just to change something if possible in the other, but also to let myself be changed by him. At any event, I had no resistance…put up no resistance to it. I began as a young man. I felt I had not the right to want to change another if I am not open to being changed by him…”

These wise words echo the old Talmudic saying that a truly wise human being is one who finds something to value and learn from in each and every other human being. Aware relating is innately and intentionally educative and transformative, allowing the relation to teach and transform others - but only on the condition that one is open also to being transformed by it, above all by being open to and learning from the uniqueness of the other – what makes them different or ‘special’, however ‘aware’ or ‘unaware’ they are.

People have their own individual feelings and world-views, values and principles, fears and desires, dilemmas and problems, hopes and potentials. ‘And’ they have relationships, more or less fulfilling. The aim of a New Yoga of active and aware relating is to bring an end to this mere ‘And’, with its implication that relationships and relating are merely an appendage or optional add-on to our lives. Its aim is also to clearly distinguish relationships from relating. Relationships are something we ‘have’ or don’t ‘have’. Relating is something we do. So the fact that people may ‘have’ or ‘be in’ relationships, whether short- or long-term, is no guarantee that they relate to one another - let alone relate with awareness. Similarly, though people engage in all sorts of relational activities with others – whether educational or economic, recreational or therapeutic, social or even spiritual – this is no guarantee that they actively relate to one another in doing so. Relational activities are no guarantee of active relating. Then again, people are aware of having all sorts of everyday practical relationships with others – whether within the workplace, family, privately or as public citizens of state and society. But this too is no guarantee they that engage in aware relational practices – practices that are not means to an end – even spiritual ends – but instead transform relating into a spiritual end in itself. For individuals can only sustain a deepened spiritual relationship to God through a transformation of the relational practices through which they engage with others - practices aimed at drawing out both the divine essence of the other and fulfilling the divine qualities and potentials at the core of their unique human individuality.

The Principle and Practice of Awareness that constitute ‘The New Yoga’ offer a wholly new dialectical and dialogical understanding of the essence of ‘Advaita’ or ‘non-duality’ - not as a more spiritual type of relation but as relation per se. They accord with Buber’s understanding that the ‘spirit’ itself is no ‘thing’ but is our relation with a divine Other or ‘Thou’ – with ‘God’. The principle of Advaitic philosophy is that we can come to experience this divine Other as a divine Self or ‘I’ within us, and within all beings – in every ‘Thou’. The seeming dualities of ‘I and Thou’ or ‘Self and Other’ dissolve as soon as we recognise that both the divine Self or ‘I’ and its divine Other or Thou are but dual poles of a singular, non-dual relation. Buber distinguishes ‘spirit’ - which he understood as an inner relation to a Divine Other or Thou - from ‘soul’, which he saw as an inner relation to the world and other human beings. The ‘self’ that is ordinarily constituted by our everyday social relations is most often the ordinary ‘worldly’ or ‘social’ self consisting of what Jung called ‘ego’ and ‘persona’. Yet what if our relation to the world and other people came itself to be centred in another self – that Self constituted by a spiritual relation to the Divine? In this way the duality of ‘spirit’ and ‘soul’, of the human being’s inner relation to the Divine on the one hand, and to the world of individual human beings on the other, would dissolve. The two relations would themselves be experienced as dual aspects of a singular relation – that relation whereby the divine itself manifests as every ‘thing’ and ‘being’ in this world. This singular relation between God and World is one that can come to be experienced in and through the relation between any two human beings. Any such relation is in turn a ‘bi-personal awareness field’ which offers a portal to Other Worlds. Hence the famous saying of Christ – “where two or more are gathered…”. In the specific Advaitic tradition known as Kashmir Shaivism, the Divine as such is understood as a dynamic relation between pure awareness on the one hand (Shiva) and its pure power of manifestation and embodiment in lived experience (Shakti). In contrast to the simple linear succession of life stages or ‘Ashrama’ of orthodox Vedic Hinduism - from student to householder or ‘family man’, and thence to community elder and renunciant hermit – the Trika or ‘triadic’ school of Kashmir Tantrism embraces the ‘Kaula’ principle of the soul family or ‘Kula’. The Kula is itself triadic in principle – for it unites a threefold set of relations - the individual in his or her singular relation to the Divine, the Divine itself as a singular relation expressed in the relational unit or couple (Yamala), and the wheel (Chakra) of couples that make up the soul group or ‘Kula’ as such. Hence the words of Acharya Abhinavagupta:

“The essence of the tantras, present in the right and left traditions, which has been unified in Kaula, lies in Trika.”

Political ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ in Tantra

Abhinavagupta wrote in the 10th century. In the immediate periods before, during and since the 20th century however, the terms ‘right and left traditions’, used in connection with ‘the tantras’ attained a wholly new political connotation - or rather revealed in new and explicit forms many historically concealed political and social dimensions of those ‘traditions’. Yet Abhinavagupta refers to ‘the tantras’ and not to ‘Tantrism’. Though the tantras were seen as possessing an inner unity, the terms ‘Tantrism’ and ‘Hinduism’ both only emerged after the British colonization of India. ‘Tantrism’ was a word first coined only in the last quarter of the 19th century by the Sanskritist Monier-Willians, who identified it with ‘Shaktism alone’, associated with ‘left-hand’ cults of the divine feminine - and denigrated it as “Hinduism arrived at its last and worst stage of medieval developments”. Yet as Hugh Urban so effectively argues in his book on Tantra - Secrecy Politics and Power in the Study of Religion, both ‘Hinduism’ and ‘Tantrism’ were not merely constructs imposed by a colonizing power but rather dialectical co-constructs of coloniser and colonised – both of whom sought to create unifying categories for the rich and diverse currents of Indian cultural religious history, indeed to ‘imagine’ the India as such, and as a ‘nation’. Tantra is for Urban an example of what Max Mueller long ago described as “that world wide circle, through which, like an electric current, Oriental thought could run to the West and Western thought returns to the East.”

Early Indian nationalism was a fusion of revolutionary anti-colonialism with religious symbols drawn from the tantras – in particular the bloodthirsty image of the great black Mother Goddess Kali – who became a symbol of the newly imagined Motherland itself in its struggle to violently purge itself of the demonic curse of white English goats or ‘Feringhees’. Hence the early language of Indian nationalism:

“Rise up, oh sons of India, arm yourself with bombs, dispatch the white Asuras to Vama’s abode. Invoke the Mother Kali. What does the Mother want? … A fowl or sheep or buffalo? The Mother is thirsting after the blood of the Feringhees. Chant this verse whilst slaying the Feringhee white goats: with the close of a long era, the Feringhee empire draws to an end, for behold – Kali rises in the East.” Bengali newspaper 1905

Bipanchandra Pal

For the colonizers too, Kali was the very image of all that was terrifying, threatening, perverse, and abhorrent in the underbelly of Indian culture - uniting obscene idolatry and sexual license with organized political subversion and criminal violence of all sorts.

“To know the Hindoo idolatry AS IT IS, a person must wade through the filth of the thirty-six pooranus … he must follow the Brahman through his midnight orgies before the image of Kalee.” William Ward 1817

“One of the most pitiful of all the manifestations of unrest … is the strange underground cult which has produced a secret bomb and revolver cult, an assassination society with secret initiation …Behind all the cruelty and sudden death of the world lies Kali, the goddess of all horror … Not even the perverted imaginations of the Marquis de Sade could devise a more horrible nightmare than Kali … to minds such as students … overstrained by premature eroticism … this deity becomes a cult in which half-mystical murder may be a dominant thought.” MacMunn 1933

In detail too thorough and extensive to summarise here, Urban shows how cults of the divine feminine or Shakti, united around the traditional tantric image of the mother goddess Kali as Chinnamasta (seemingly trampling on the supine body of her own god and consort Shiva) came to constitute, in Walter Benjamin’s terms, a ‘dialectical image’ - “used not only to represent the humiliation of modern India but also to arouse revolutionary fervor and violence”. He also shows how it was used to evoke a counter-image of the Bengali male as possessed of a powerful, warrior-like masculinity – in contrast to the English image of the weak and effeminate ‘babu’. Paradoxically however, this very counter-image represented a submission to a Western concept of masculinity in diametric opposition to the traditional tantric identification of the divine masculine (Shiva) with ‘Purusha’ - a ‘zero-point’ state of pure awareness, absolute stillness and non-action - from and through which alone the boundless power (Shakti) of the divine feminine rises. It seems that this paradox was not lost on Sri Aurobindo, who, after withdrawing from militant, religiously-fuelled political activity re-established in his own life and philosophy the earlier tantric identification of the divine masculine with ‘Purusha’ or Pure Awareness, and of the divine feminine, personified by Kali, as a Pure Power of universal embodiment and manifestation. Aurobindo nationalist spiritual universalism counterposed the spiritual culture of India to the degenerate materialist culture of the capitalist West.

Such sentiments were echoed in the writings of colonial judge Sir John Woodroffe, alias ‘Arthur Avalon’, who sought to rescue ‘Tantra’ from the defamations of his British Imperial peers, arguing in contrast to Monier-Williams that - above all in the form of Tantrism - “India possessed a wonderful solvent, a solvent of irreligious materialism.” Western civilization on the other hand was: “a great eater. We consume. What is called a ‘higher standard of life’ has meant that we consume more and more. Industrialisation, instead of satisfying has increased our Western needs. We want more wants.” In a prescient anticipation of the economic ‘rise’ of India in today’s global market economy he also warned that:

“India is now approaching the most momentous moment in its history … The country will be subject to the play of monster economic forces … the world-vortex …Will she have the strength to keep her feet in it. I hope she may.”

What he did not and could not anticipate at the time was that as capitalism continued its historic global march, it would begin to colonise, consume and then turn into marketeable commodities the very spiritual traditions and teachings which others had relied upon to halt that march.

An early but notably strident affirmation of this tendency towards the commodification and consumerisation of ‘tantra’ can be found in several sayings of the ‘neo-Tantric’ guru, Acharya ‘Osho’ Rajneesh:

“The materially poor can never be spiritual.”

“Capitalism has grown out of freedom.”

“I sell enlightenment.”

Rajneesh began his guru career precisely by speaking against socialism, and when he later discoursed on ‘Tantra’ he did so in a way that led it to be perceived as a mere form of liberated spiritual hedonism – ‘aware indulgence’ or ‘sacred sex’ – yet of a sort lacking any roots in the spiritual intellect and the profound theological comprehensions and practices of the Kashmiri Shaivite tantras.

In contrast to Rajneesh (1931-1990) the Marxist scholar Narendra Nath Battacharya (1887-1954) found in the history of the tantras “evidence for an archaic, class-free society, based on matriarchy and the power of the labouring classes – a system that would eventually be replaced by Brahmanical Hinduism and its patriarchal, class-based social order.” (Urban) Battacharya emphasised that “Throughout the ages, the Female Principle stood for the oppressed peoples, symbolising all the liberating potentialities in the class-divided, patriarchal and authoritarian social set up of India … the success of Shaktism could not be checked because it had its roots among the masses.”

His view was that India’s primordial matriarchal culture was akin in nature to Marx’s notion of an archaic form of communism. Within it ‘tantra’ was, according to Bhattacharya, more than a system of spiritual knowledge, for it also or above all offered the masses worldly knowledge in a broad range of areas of life and productive activity. Yet the very division between spiritual and worldly knowledge is a false dualism. For expanded awareness is the common source of both ‘spiritual’ inspiration, insights and intellectual comprehensions on the one hand, and intellectual intuitions related to practical ‘worldly’ activities and relationships on the other. Unable to integrate ‘Marxism’ and ‘Moksha’, Bhattacharya ended up retreating from Marxism into Humanism whilst at the same time never reaching for or attaining any feeling sense or experience of Religious truth.

Nevertheless, the use of tantric religious symbols as “weapons of insurgency or tools for revolutionary struggle” (Urban) continued. For meanwhile in Europe, two central figures – Mircea Eliade and Julius Evola – came to represent extreme right-wing exponents of the new Tantrism, held up as the sole tradition capable of providing a liberating counter-force to the irreligious degeneracy of Western ‘modernism’. According to Eliade “It is only in modern societies of the West that non-religious man has developed fully … the sacred is the prime obstacle to his freedom … he will not be truly free until he has killed the last god.” Yet like Battacharya – and indeed many other scholars of Indology - Eliade related Tantra to a “pre-Aryan popular strata” through which it “made its way into Hinduism”. In contrast, Evola was no populist but an aristocratic elitist and ‘conservative revolutionist’ in the German sense, racist, but with a spiritual rather than Nazi-biological concept of race:

“Tantrism may lead the way for a Western elite which does not want to become the victim of … experiences whereby an entire civilization is on the verge of being submerged.”

Writing of it as ‘The Yoga of Power’, Evola saw in Tantra a means for the de-emasculation of modern man – a path of heroic, free, individualist and elitist counter-revolution aimed at an emaciated Christian morality and an emasculated democratic and modernist culture. In his own words: “We may consider typical of Tantric speculation a metaphysics and theology of Shakti, namely of the principle of Power, or of ‘the active Brahman’.”

Noticeable is that all the figures we have mentioned so far identify Tantrism primarily with Shaktism rather than Shaivism, even whilst acknowledging, albeit to a greater or lesser extent, and with greater or lesser depth of knowledge, the Kashmir identificiation of divinity with Shiva-Shakti. This is something of great import in attaining a new and unified understanding of both the spiritual and political meanings of ‘left’ and ‘right’ traditions in tantra – with their double connotation of ‘left-hand’ and ‘right-hand’ on the one hand, and ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’ on the other. For it was the left-hand tantric tradition that was associated with Shaktism, not simply as worship of the divine feminine but also with practices and rituals that incorporated physical intercourse, and in which paradoxically, the female tantric partner or Yogini could either play the decisive initiatory role herself – as guru – or else be reduced to a mere dispensable spiritual object and appendage for the male Yogin or Tantrika (such paradoxically misogynistic ‘Shaktism’ having been carried to extremes in Tibetan Buddhist tantric practices).

Whereas the practices of ‘left-hand’ tantra associated with traditional Shaktism culminated in a relation of outward bodily and sexual intercourse (Maithuna) between human partners – in a way that also left them more open to misogynistic perversion - the relational dimension of ‘right-hand’ tantra understood Maithuna as an experience of inner spiritual union or ‘intracourse’ within the individual between the divine feminine and the divine masculine. Paradoxically then, though left-hand tantra was associated with Shaktism and the divine feminine, in practice it often was seen and used as a means for the andocentric empowerment and liberation of the male rather than the female partner – hence its association with masculinist and politically right-wing practitioners. Conversely, it was right-hand tantra – which excluded in principle all possibility of misogynistic perversion in the service of male empowerment - had an intrinsically ‘left-wing’ political character. ‘Shaktism’ then is itself a deeply paradoxical or dialectical concept, for though ‘Shakti’ means ‘power’ or ‘that which empowers’ - the question has always remained ‘whose power’ and ‘whose empowerment’? That of the male practitioner through spiritual exploitation of females, that of the female as initiatory guru or a truly mutual experience of ‘awareness bliss’ (Chitananda) attained through the male partner’s identifying with the Shaiva principle of pure awareness and in this way liberating in the female partner the Shakta principle of pure power? In the era of feminism and sexual ‘liberation’ inaugurated in the sixties, it was all too easy to resolve this question by reducing the ‘left-hand’ path of Shakta Tantrism to some mutually heightened and supposedly spiritualised experience of sex - thus reducing the sensuality and sexuality of the soul (heightened awareness) to that of the body. Hence the now almost universal identification of Tantra, in both the popular mind and mass media, with ‘Tantric Sex’.

As ‘Tantric Sex’ the Total Americanisation of Tantra has now become its complete ‘Californication’, both in name and effect a new ‘Church of Tantra’ aiming at nothing more than spreading and selling itself on the world-wide web. Thus, as Urban remarks:

“One need only enter the word ‘tantra’ into any good search engine to generate several hundred sites [a wild underestimation!] bearing titles such as ‘Sacred Sex: Karessa, Tantra and Sex Magic’, ‘Extended Orgasm: A Sexual Training Class’, ‘Oceanic Tantra’, or ‘Ceremonial Sensual Pleasuring’.”

The language of the example he cites is one of orgasmic ‘doing it’ and ‘making it’ rather than Awareness and Being. Its thought content can be compared to premature ejaculations of the adolescent mind, fuelling nothing more than fantasies of sexual gratification and economic gain:

“The Sex Magic Reality Creation Process is about maintaining one’s focus during orgasm and channeling the energy into creating reality, any reality, whether its creating a new job, car, experience, relationship etc. … What is your life like when you earn $85,000? What does it FEEL like? Make it big, in Technicolor … do whatever brings you to orgasm ...” The Church of Tantra website

‘Kundalini’ is reduced to a single mantra: “Juice it up, way up!” The ‘it’ to be juiced up here is clearly not the nectar or Amrita of the tantras – the serpentine, sensual bliss-substantiality of pure awareness. And since nothing is further removed from the divine- sexual dimension of the tantras than biological orgasm, the ‘mantra’ of this American ‘Church’ merely announces the global ‘Coca-colonisation’ of ‘Tantra’ as a religion of material success and sexual hedonism, one perfectly in congruence with the ‘American Dream’. This is distorted ‘left-hand’ tantra of the most historically ignorant and politically right-wing capitalist type. We might well enquire then, what remains or has become, meanwhile, of the ‘right-hand’ tradition, and its relation to the socio-political ‘left-wing’ dimension of the tantras?

For as the right-wing advocates for Tantra, Evola and Eliade had reminded us - or rather warned us:

“We have now reached the last era, the dark age or Kali Yuga, which is a period of dissolution.”

Julius Evola

“Humanity is fallen: it is now a question of swimming against the stream …”

Mircea Eliade

Yet whilst “… the tantrika does not renounce the world; he tried to overcome it while enjoying perfect freedom” the fact remains that “Against the terrors of history there are only two possibilities of defence: action or contemplation … Our only solution is to contemplate, that is to escape from historic time to another Time.”

Stefan, in Mircea Eliade, The Forbidden Forest 1954

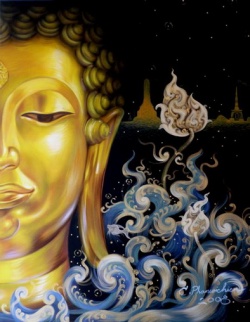

Such words are much more an affirmation of the ‘right-hand’ tradition, for they point to the trans-historical dimension of time into which true tantric meditation leads. This is the experience of Kali as the trans-temporal essence of time (Kala) itself, the circumscribing circle, sphere or womb of an infinite time-space of awareness within which our personal worldly concerns - and those of the current world at large - appear as transitory and diminutive in the larger scale of things.

The importance of deep metaphysical understandings of Tantra was emphasised by Agehananda Bharata, when he wrote that:

“Tantrism, like yoga and Vedanta … could be respectable in the Western world, provided that the traditions of solid scholarship, of learning and intellectual effort … did accompany their migration into the occidential world. Without these, I regard them as fraudulent.”

Agehananda Bharata The Tantric Tradition

And indeed, in recent decades much ‘solid’ but intelligent and also sympathetic and feeling scholarship, particularly on the subject of ‘Kashmir Shaivism’, has found expression in the work of such leading figures as Muller-Ortega (The Triadic Heart of Shiva) and Mark Dyczkowski (The Doctrine of Vibration). Much is owed here to the pioneering work of Heinrich Zimmer on ‘The Philosophies of India’. Born in 1890 and holder of the chair of Indian philology at Heideberg University until 1938, he was forced to emigrate to Oxford by virtue of his marriage to a German-Jewess. As Urban records:

“Throughout his career, Zimmer’s life and scholarship were intimately related: as his daughter recalls, his spiritual vision and his object of study were inseparable, fuelling him in a prolific search for meaning: ‘life and learning for him were never separated. All his work was part of his life and his life part of his work’.”

Like the scholars of head and heart that followed him he recognised in the tantras a synthesis of the Brahmanical intellect at its best with the “archaic matrilineal world-feeling of the aboriginal civilization of India.” And though he never once set foot on Indian soil, through the “initiatiory ordeal” of the First World War, he also saw the contemporary significance of this synthesis, anticipating how - in our new modern ‘Dark Age’ or dark modern ‘New Age’, humanity “will tear to pieces the body of his mother, Nature, and will quarry her for new and different forms of power.” However Zimmer’s understanding of the metaphysics of Tantra as a historical synthesis (culminating in the writings of Abhinavagupta and the Trika school of Shaivism) contrast radically with earlier views, shared by both European scholars and Indian religious reformers such as Rammohun Roy, that Tantrism was the scourge of India, the source of her downfall, and a shameful degradation - “utterly devoid of every moral principle” - of the Aryan-Vedic religious tradition.

“If at any time in the history of India the mind of the nation as a whole has been diseased, it was in the Tantric age, or the period immediately preceding the Muhammedan conquest of India … Someone should take up … the diagnosis, etiology, pathology and prognosis of the disease so that more capable men may take up its treatment and eradication.”

Benyotosh Bhattacharya

“… the purity of the race was soiled by marriage with native women … and the creed with foul Dravidian worships of Shiva and Kali, and the adoration of the lingam.”

Isaac Taylor, The Origin of the Aryans, 1889

Such a view contrasted radically with the tantras revered in medieval India itself, not least the Kulanarva Tantra, whose hierarchical synthesis of religious doctrines and practices would later be adopted and crowned by Abhinavagupta with the Trika school of Kashmir Shaivism.

“Vedic worship is greater than all others. But greater than that is Vaishnava worship; and greater than that is Shaiva worship; and greater than that is Dakshinachara. Greater than Dakshinachara is Vamachara; and greater than Vama is Siddhanta; greater than Siddhanta is Kaula. Devi, this Kula is more secret than secret, more essential than the essence, greater than the supreme, given directly by Shiva, proceeding from ear to ear.”

Kulanarva Tantra

What a contrast also with the words of Sir John Woodroffe:

“The full inclusion of the feminine element in public life will be the great fight of the immediate future … These circumstances, and the manner in which they are capable of being met by Tantra Shastra (Tantric Teachings) give another ground for the belief that this ancient scripture will become one of the religious influences of modern life, not … superseding Christianity, but in an interaction through which the Shakta Shastra will help … to produce a Mother-pearl of a complete and true religious exegesis.” Sakti and Sakta

But let us return to our central theme of ‘Marxism and Moksha’, and with it the quest for a revolutionary Tantra and ‘Red Banner of Rudra’ relevant to our own times. For historical scholarship alone, however thorough, sympathetic or even divinely inspired and devout (as exemplified by the life work of Lakshmanjoo) bears with it the danger of merely offering us a retreat to the religious language and traditions of earlier historical era - thus not only evading Eliade’s admonition “to escape from historic time to another Time” but also leaving us with nothing to say about our time, let alone providing a radically new and revolutionary direction for its transformation.

It is in this politically leftward direction that Urban points to the work of Gopinath Kaviraj (1887-1976), whom he describes as “undertaking a synthesis of the various Tantric traditions” similar to that of Abhinavagupta himself. Yet as Urban stresses;

“Surely the most fascinating and original aspect of Kaviraj’s system is his new vision of Tantra, which is now conceived as something far more than a quest for individual liberation. For Kaviraj, Tantra has the potential to achieve a collective salvation or universal liberation for humankind.”

How Kaviraj believed this liberation might come about is summed up by the following citation from Arlene Mazak’s dissertation on Gopinath Kaviraj’s Synthetic Understanding of Kundalini Yoga in Relation to the Nondualistic Hindu Tantric Traditions:

“The mahayogin who has attained his own integral Self-realisation must look back compassionately upon all people sunk in their collective ignorance and dedicate himself to winning the integral Self-realisation of the entire world … One mahayogin, working prodigiously within one lifetime, could eventually become identified with paramashiva as the imperishable purusha sleeping on the supercausal ocean. If this mahayogin could then awaken from the world-dream while still holding the physical body, the root ignorance in absolute subjectivity would disappear and the new kingdom of dynamic consciousness (chaitanya) would be created…”

Here we find a trans-national and deeply esoteric expression echo, in the late 20th century, of the national-political message of the renowned 19th century visionary mystic Ramakrishna, who spent most of his life as a priest of Kali at the temple of Dakshinesvar.

“We must conquer the world through our spirituality … we must do it or die. The only condition of awakened and vigorous national life is the conquest of the world by Indian thought.”

Yet it is not Indian thought that is currently seeking to conquer the world and overcome the ‘non-Dharmic’ or ‘Abrahamic’ faiths – Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Nor is ‘Kashmir Shaivism’ or ‘Shaivist Tantrism’. Instead it is Tibetan Buddhism and Buddhist Tantrism. In this context it is interesting to note the resonance between the words of Kaviraj - and the role he allots to a singular ‘Mahayogin’ - and the Buddhist ideal of the compassionate Buddha or Bodhisattva as historic world-saviour and ‘Mahasiddha’.

‘Kashmir Shaivism’, ‘Tibetan Buddhism’ and the ‘Rudra Chakrin’

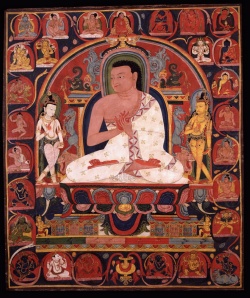

Returning to the apparent ‘left-right’ dualism of ‘Shaivism’ and ‘Shaktism’ we must note a fundamental distinction between Indian and Buddhist Tantrism. Indian Tantrism was rooted in worship of the Great Mother Goddess Kali. In the understanding of Kashmir Shaivism offered by The New Yoga, Shiva himself, as pure and absolute awareness is a constant meditation of the realm of undifferentiated potentialities of awareness which is the creative matrix or womb of the Great Mother. It is out of Shiva’s meditation of the Mother, this being a pure awareness of the pure potentiality or power (Shakti) latent within awareness - that this at first undifferentiated power differentiates and manifests itself as countless Shaktis – emerging through the light of the One Supreme and Pure Awareness that is Shiva from the dark womb of the One Supreme Power or Shakti (Paramashakti) that is the Mother Goddess. Hence the opening sutras of Abhinagagupta’s Tantraloka:

“May my heart throb, which is pure, seat of art, creative by the coupling state of Shiva and Shakti, Shakti (Mother Devi) who is creation, the cosmos and the divine mother and Shiva who … offers the internal bliss and external expansion…”

“I bow down to the deity Pratibha (Paramshakti) who is beyond, infinite and rests in the Supreme Awareness at the seat of the divine lotus situated in the threefold state beyond mind.”

‘Shaivism’, understood in this way is the very essence of ‘Shaktism’. In contrast there are forms of ‘Shaktism’ whose principle aim is not the recognition of the dynamic relational unity or non-duality of Shiva and Shaki - the divine masculine and divine feminine – but rather the incorporation of the latter into the former, of the feminine into the masculine. In their detailed research on this subject, available on the internet as an extensive text under the title ‘The Shadow of the Dalai Lama’, Victor and Victoria Trimondi argue that the very essence of both early Buddhism and the ‘Diamond Vehicle’ of Tibetan Buddhist Tantrism (Tantrayana) is ‘androcentrism’ - the subjugation, subordination and sacrifice of the divine feminine to the divine masculine. They themselves spell out their ‘core hypothesis’ as follows: “The mystery of Tantric Buddhism consists in the sacrifice of the feminine principle and the manipulation of erotic love in order to attain universal androcentric power.” Rather than seeking to summarise the evidence they provide for this core hypothesis in all its historical detail, I will cite here only their own amplification and summation of its aims and claims, and the conclusion they draw from it:

“It is the goal of the present study to work out, interpret and evaluate the motives, practices and visions of Tantric Buddhism and its history. We have set out to make visible the archetypal fields and the “occult” powers which determine, or at least influence, the world politics of the Dalai Lama as the supreme representative of Tantrayana.

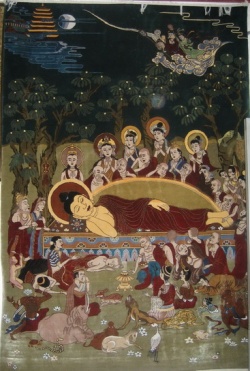

1. The “sacrifice of the feminine principle” is from the outset a fundamental event in the teachings of Buddha . It corresponds to the Buddhist rejection of life, nature and the soul. In this original phase, the bearer of androcentric power is the historical Buddha himself.

2. In Hinayana Buddhism, the “Low Vehicle”, the “sacrifice of the feminine” is carried out with the help of meditation. The Hinayana monk fears and dreads women, and attempts to escape them. He also makes use of meditative exercises to destroy and transcend life, nature and the soul. In this phase the bearer of androcentric power is the is the ascetic holy man or Arhat.

3. In Mahayana, the “Great Vehicle”, flight from women is succeeded by compassion for them. The woman is to be freed from her physical body, and the Mahayana monk selflessly helps her to prepare for the necessary transformation, so that she can become a man in her next reincarnation. The feminine is thus still considered inferior and despicable, as that which must be sacrificed in order to be transformed into something purely masculine. In both founding philosophical schools of Mahayana Buddhism (Madhyamika and Yogachara), life, nature, the body and the soul are accordingly sacrificed to the absolute spirit (citta). The bearer of androcentric power in this phase is the “Savior” or Bodhisattva.

4. In (Buddhist) Tantrism or Vajrayana, the tantric master (yogi) exchanges compassion with the woman for absolute control over the feminine. With sexual magic rites he elevates the woman to the status of a goddess in order to subsequently offer her up as a real or symbolic sacrifice. The beneficiary of this sacrifice is not some god, but the yogi himself, since he absorbs within himself the complete life energy1 of the sacrifice.

If, as the adherents of Buddhist Tantrism claim, a logic of development pertains between the various stages of Buddhism … the relationship of the three schools to the feminine gender must be characterized as fugitive, supportive and destructive respectively. Should our hypothesis be borne out by the presentation of persuasive evidence and conclusive argumentation, this would lead to the verdict that in Tantric Buddhism we are dealing with a misogynist, destructive, masculine philosophy and religion which is hostile to life — i.e., the precise opposite of that for which it is trustingly and magnanimously welcomed in the West, above all in the figure of the Dalai Lama.”

Victor and Victoria Trimondi The Shadow of the Dalai Lama www.trimondi.de

Despite taking this strong and hostile position, it is noteworthy that in their Postscript, the Trimondis accept in principle the positive, life-affirming and revolutionary potential of a religious and political world view truly founded on the tantric God-concept of a divine masculine-feminine pair i.e., on a divine relation rather than a divine being, masculine or feminine. What they see as the disguised esoteric goal of ‘Lamaism’ – namely the global establishment of a traditionally androcentric and misogynistic Tibetan-Buddhist Theocracy or ‘Buddhocracy’ is at odds with the Dalai Lama’s own assertion (which they cite) that an ideal solution to the world’s problems lies in a synthesis of Buddhism and Marxism – and his critique of the retreat from Marxism into crude capitalist materialism by the current, post-Maoist rulers of China.

Tibetan and Asian Buddhism and Tantrism were born from the womb of India’s Vedic-Brahmanic culture. The chief question raised by the work of the Trimondis is whether this birth, like that of a distorted Christianity from Judaism, was, if not as a whole, then at least in part - a deformed birth - a misogynistic miscarriage or abortion. If so - and given the current Western ‘fashion’ for Buddhism and the consumerisation of diluted Buddhist ‘meditation’ as a palliative to the ‘stresses’ of capitalism - then the challenging task of giving birth from Indian thought to a new ‘Buddhism’. By this I mean a trans-Buddhist and authentically revolutionary form of global tantric religiosity and theocracy. In not ‘Buddhism’ as we know it but a new ‘Tantrism’ beyond Hinduism, Buddhism and Taoism – remains the challenge of the day. It is this challenge that ‘The New Yoga’ is a response to. In this connection, and in the context of the title of this work, it is notable that in the Kalachakra Tantra – in essence the esoteric grand plan of Buddhist Tantrism to subvert and overcome the global theo-politics of the non-Dharmic or Abrahamic religions – a key role is played by a wisdom being called the Rudra Chakrin2. ‘Chakrin’ means ‘wheel-turner’ and is thus a direct synonym of ‘revolutionary’. Given that Shiva is associated with the destructive Vedic god Rudra, the term Rudra Chakrin is interpreted as wrathful ‘wheel turner’ or revolutionary. Yet this interpretation ignores the simple root association of the names Rudra and Shiva (from Tamil Civa) with ruddiness, redness or reddening. The Rudra Chakrin is, quite literally the ‘red’ or ‘reddening’ religious ‘wheel turner’ or revolutionary. Symbolically, it is a curious yet significant paradox that the culmination of the Buddhist Tantras should raise ‘The Red Banner of Rudra’ in its search to unite ‘Marxism and Moksha’.

Yet any ‘red’ agenda of Buddhism in the Marxist or left-wing sense is totally belied by the spiritual politics of the Dalai Lama’s chief American advocate, Robert Thurman. For in his audaciously red-covered book entitled ‘Inner Revolution’, he reveals a total lack of any Marxist understanding of the nature and innate contradictions of capitalist economics. The book ends up presenting a ‘Political Platform Based on (Buddhist) Enlightenment Principles’ which reveals his true political colours, boiling down as it does to a selection of the most yellow-bellied and tepid of ‘liberal’ policies of the sort which merely tamper at the edges of capitalist injustice (for example a ‘revolutionary’ proposal for graduated income tax, reduced military expenditure and the abolition of the death penalty). His political ideals and idealism do indeed centre on the idea of ‘Moksha’ as individual liberation. Yet this is watered down to a repetition of weak and outworn liberal mantras concerning of the rights and freedoms of individuals - rights and freedoms of the sort long entrenched in the U.S.Constitution, yet which are denied in practice by the de facto power of the wealthy over the poor and the blatant, money-buys-power corporate plutocracy that is the true reality of U.S. ‘democracy’.

Thurman’s view of history is as naïve as his political ‘platform’ - opposing a Buddhistically Enlightened “inner modernity” in the form of Tibet’s spiritual and religiously-motivated, monastic society3, with the “outer modernity” of those secular, materialistically-driven and militaristic states that evolved in the West after the European Reformation and its ‘Enlightenment’.

Thurman’s vision of the future seeks only to combine the old Buddhist principle of “emptiness of self” with a revival of traditional monasticism. Yet no form of monastic education narrowed solely to the confines of any Eastern religious traditions, scriptures and philosophies can do them true service – revealing both the complexities of their inner relation to the history of Western philosophy, science and social relations – and their profound relevance for a revolutionary transformation of the latter. And “emptiness of self is no recipe for what I have termed relational revolution. Only if ‘emptiness’ is understood as a pure, non-attached awareness of our own human self can it give rise to deep empathic resonance with others – and thus fulfill the much-vaunted Buddhist principle of ‘compassion’. Otherwise, the sole uniting factor between ‘self and other’ is “emptiness” itself and the term ‘compassion’ is emptied of all relational meaning. For as Buber emphasised, without an authentic Self or ‘I’ there can be no authentic relation to another as a ‘Thou’. Through The New Yoga, the term ‘authentic’ is itself given a new and precise meaning - as both an awareness of our personal, human self in all its individualised and multi-faceted aspects and the recognition of its innate non-dual relation to a divine, trans-personal Self. The latter is that Self (Chaitanya Atman) which, like the Divine, is identical with awareness as such. ‘Enlightenment’ from this point of view is not a negating ‘emptiness’ of self but an affirming awareness of self - an awareness identical with that Divine Awareness of which every being, not least every human being, is a unique living expression and embodiment. It is through awareness and not “emptiness” of self, that, as Thurman writes “… the adept is always himself and the other at the same time”, and thus a living embodiment of ‘Relational Revolution’4.

Notes:

1. The sexual dimension of The New Yoga as ‘Tantra Reborn’ is very far removed from the use of physical intercourse to drain what they call the ‘gynergy’ from a women in order to revitalise or empower a male yogin. On the contrary, it is about the use of pure awareness on the part of the yogin, identified with the pure awareness that is Shiva, to evoke and draw out the vital power of Shakti of the female partner or yogini – thus empowering her and transforming her into a living embodiment of the divine feminine. This is a sexual tantra of the ‘soul body’ and not the physical body. As such it transcends the dualism of left-hand practices based on physical body intercourse between partners and ‘right-hand’ practices based purely on a divine ‘intracourse’ of soul within the awareness of the solitary practitioner.

See Tantra Reborn – on the Sensuality and Sexuality of the Soul Body

New Yoga Publications / Exposure Publishing 2007

2. “Let us return to the Rudra Chakrin, the tantric apocalyptic redeemer. He appears in … the epoch of the ‘not-Dharmas’, against whom he makes a stand …Before the final battle … the planet is awash with natural disasters, famine, epidemics and war. People have become ever-more materialistic and egoistic. True piety vanishes. Morals become depraved. Power and wealth are the sole idols. A parallel to the Hindu doctrine of the Kali yuga is obvious here … In these bad times, a despotic ‘barbarian king’ forces all nations other than Shambhala to follow his rule.”