The First Four Themes of Klong chen pa’s Tshig don bcu gcig pa by Daniel Scheidegger

The First Four Themes of Klong chen pa’s Tshig don bcu gcig pa by Daniel Scheidegger (Université de Berne) ith regard to the text The Eleven Themes (Tshig don bcu gcig pa) composed by Klong chen rab ‘byams (1308-1364) it has to be mentioned that one is dealing with a short — it consists of only 65 pages — but nevertheless comprehensive text. This text out of which the first four themes will be translated and commented upon in this article is contained in the fourth volume of the Bi ma snying thig which again forms part of the Four Branches of the Heart Essence (Snying thig ya bzhi). As its name suggests, it deals with eleven main topics arranged into Eleven Themes:

1. “The essential condition of the ground in the time preceding the presence of Buddhas realizing it and of sentient beings failing to do so” presents a list of the Eleven Themes treated in this text as well as a concise explanation of the three aspects of the ground, i.e., of its essence (ngo bo), its nature (rang bzhin), and its compassion (thugs rje). Moreover, it is stated that this text is not meant for individuals preferring a rather gradual approach towards Buddhahood by means of studying philosophical tenets, but for those who are ready to realize it directly through practice.

2. “The assessment of the origin of delusion in the ground (gzhi) as de- fined in the First Theme” deals with its arisal as samsara on account of ignoring its appearance as self-appearance (rang snang). Ignorance itself consists of three aspects being closely related to the three aspects of the ground and it is accompanied by four conditions which support this process of going astray into samsaric delusion. 3. “The presence of the core or seed of perfect Buddhahood in sentient beings (sems can) despite the already arisen delusion” treats the different modalities of such a presence. Thus, it is explained that this seed dwells as Five Buddha Families (rigs lnga), as Five Buddha-Bodies (sku lnga) , etc.

4. “The precise location of the seed or essence of perfect Buddhahood” elucidates the Precious Palace of the Heart (tsitta rin po che'i gzhal yas khang) which is said to be located in the middle of the heart.

There, the essence of this seed dwells as Buddha-Body, its nature as light, and its compassion as Awareness.

5. “The way taken by Pristine Cognition” gives an outline of the formation of the body. It is argued that one has to learn first about the definite characteristics of the body in order to understand the light-channels (‘od rtsa) which are based on the body and which constitute the way taken by Pristine Cognition (ye shes).

6. “The doors by means of which Pristine Cognition arises” explains the place where Pristine Cognition parts from the body in order to manifest itself outwardly.

It is said to be the eyes, or more precisely, the Lamp of the Water that Lassos Everything At a Distance (rgyang zhag chu’i sgron ma), a subtle light-channel dwelling in the eye.

7. “The place where Pristine Cognition appears” treats the Inner Space (nang dbyings) of the Precious Palace of the Heart as it is projected in and as Outer Space (phyi’i dbyings). Moreover, “Space” (dbyings) is considered in this context as being inseparably united with Pristine Cognition (ye shes).

8. “The practice” sketches out two ways of how to meditate, one emphasizing a rather conceptual and the other a non-conceptual, i.e., a direct approach. The first one consists of Four Yogas (rnal ‘byor bzhi) and the second one has as its two parts the Cutting Through (khregs chod) and the Leaping Over (thod rgal). It is in the context of the latter one that the Four Visions (snang ba bzhi) are dealt with.

9. “The marks of progress in practice” gives indications about how body, speech, and mind are felt in the wake of meditative progress. Moreover, as for Awareness (rig pa), the two marks of Awareness itself and of its self- appearance are distinguished.

10. “The arising of the intermediate State of Reality Itself in the time fol- lowing death after having failed to practise during life” presents first an outline of the Four Intermediate States (bar do bzhi) and then focuses on the Intermediate State of Reality Itself (chos nyid kyi bar do) which is described as the experience of a multitude of luminous forms.

11. “The great liberation” ascertains the result, i.e., Buddhahood which is understood as an inseparable union of the Inner Space of the Precious Palace of the Heart and its projection into the Outer Space with the Intermediate Space of the Four Lamps (sgron ma bzhi).

Being rather short, the text The Eleven Themes (Tshig don bcu gcig pa) helps us not to loose the overall view. On the other hand, many questions concerning its eleven topics remain unanswered on account of its brevity. Therefore, other texts stemming from The Four Branches of the Heart Essence (Snying thig ya bzhi), The Hundred Thousand Tantras of the Old School (Rnying ma rgyud ‘bum), and The Seven Treasures (Mdzod bdun) have been consulted in order to gain a precise understanding of its content. Last but not least, it has to be mentioned that it was absolutely necessary to consult Tibetan Rdzogs chen adepts, because the salient aspects of Rdzogs chen thinking have been exclusively transmitted “from mouth to ear” from ancient times until now.

— The First Theme — The essential condition of the ground in the time preceding the presence of Buddhas realizing it and of sentient beings failing to do so “With body, speech, and mind I pay homage to the Great Glorious Vajradhara, to the Guru, the Deva, and the Ḍākinī who are the cause of bliss coming forth. Thus, the teacher Samantabhadra (Kun tu bzang po), the Perfect Buddha whose compassion is great and whose means are skilful, appeared out of the Clear Light of the dharmakāya (chos sku) in the form of the sambhogakāya (longs sku) with ist major and minor marks (mtshan dang dpe byad). There are different kinds of beings to be tamed, but here Eleven Themes (tshig don bcu gcig) (are explained) in order to let a fortunate individual realize Buddhahood.

The First Theme (explains) the essential condition of the ground in the time preceding the presence of Buddhas realizing it and of sentient beings failing to do so.

The Second Theme asseses the origin of delusion in the ground as defined in the First Theme.

The Third Theme (elucidates) the presence of the core or seed of perfect Buddhahood in sentient beings despite the already arisen delusion.

The Fourth Theme (deals with) the precise location of the seed or essence of perfect Buddhahood. The Fifth Theme (treats) the way taken by Pristine Cognition.

The Sixth Theme (specifies) the doors by means of which Pristine Cognition arises.

The Seventh Theme (describes) the place where Pristine Cognition appears.

The Eighth Theme (gives an outline of) the practice. The Ninth Theme (clarifies) the marks of progress in practice.

The Tenth Theme (delineates) the arising of the Intermediate State of the Nature of Reality in the time following death after having failed to practise during life.

The Eleventh Theme (defines) the great liberation. Now, as for the First Theme: In the general Rdzogs chen system, (one distinguishes) adepts of philosophical tenets (rdzogs pa chen po'i lugs kyi grub mtha'i rjes su 'brangs pa) and adepts of its practice (lam rjes su'dzin pa'i gang zag). From among these two, (this text is meant) for the latter one. Thus, the original ground (thog ma’i gzhi) is present as essence (ngo bo), nature (rang bzhin) and compassion (thugs rje). Its essence is empty, its nature clear and its compassion unobstructed.

Its essence is present as Buddha-Body (sku), its nature as Buddha-speech (gsung), and its compassion as Buddha-Mind (thugs). Its essence is present as Buddha-Body without throne and ornaments, its nature lights up in manifold colours, and its compassion is all-pervading (kun khyab) as it is present as unobstructed ground for the arising of anything. As its essence is empty, it falls not in the extreme of eternalism. Being clear in its nature, it falls not in the extreme of nihilism, and as it pervades all, its falls not in the extreme of being material. Its essence is not present as error. So, there is no possibility of its compassion abiding as error. As its essence is the Buddha-Body, its does not change. As its nature is light, it is self-clear. As its compassion is Pristine Cognition, the aspects of knowing are unceasingly clear in their distinctiveness.

Its aspects of knowing are present as the three aspects of the Pristine Cognition abiding in the ground (gzhi gnas pa'i ye shes gsum). Such is the mode of being of the initial ground.” In the beginning of the text, the author takes refuge (phyag ‘tshal) in the Great Glorious Vajradhara (Dpal ldan rdo rje ‘chang chen) and the Three Roots (rtsa ba gsum)1 . After that one is told that the dharmakāya Samantabhadra (chos sku kun tu bzang po) has arisen as sambhogakāya longs sku) with its Major and Minor marks (mtshan byed)2 in order to transmit this text to sentient beings (sems can) with good karma.

Furthermore, it is stated that one can attain Perfect Buddhahood (yang dag par rdzogs pa’i sangs rgyas) in this life or in the Inter- mediate States of Death, of Reality, and of Becoming, by following the instructions given in it. Two kinds of Rdzogs chen adepts are mentioned, namely the adepts of philosophical tenets and the adepts of its practice.

Klong chen rab ‘byams makes it unmistakebely clear that this text is meant for the latter ones. Altogether seven views or assumptions concerning the ground (gzhi) of Rdzogs chen are mentioned. Six of them are ascribed to the the adepts of philosophical tenets and are considered as only partially correct3:

1. The assumption that the ground is spontaneously perfect (gzhi lhun grub tu ‘dod pa),

2. the assumption that it (the ground) is indeterminate (ma nges par ‘dod pa),

3. the assumption that it is ultimately determinate (nges pa don du ‘dod pa),

4. the assumption that it is completely changeable (cir yang bsgyur btub tu ‘dod pa),

5. the assumption that it is acceptable as anything (gang du’ang khas blangs du rung bar ‘dod pa), and

6. the assumption that it is variegated on account of its many aspects (rnam pa sna tshogs pas khra bor ‘dod pa). 1.

Why are these six assumptions only partially correct? Let’s begin with the assumption that the ground is spontaneously perfect: To consider the ground as something exhibiting deficiency and freedom of deficiency in spontaneous perfection is inconsistent with the primordial purity of it. Besides, it would not make any sense to walk on the way of meditation. Such a way could not lead towards Buddhahood, because nothing would be attained if deficiency and freedom of deficiency were spontaneously perfect forever.

2. The assumption that it is indeterminate exposes one to the danger of imagining it to be something. Being completely indeterminate, samsara with all its suffering could arise again even after having reached Buddhahood.

1 On the Three Roots (rtsa ba gsum), i.e., Guru (bla ma), Deva (yi dam), and Ḍākinī (mkha' 'gro), see Sky Dancer: The Secret Life and Songs of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel, pp. 217-225. London, Routledge and Kegan Paul. 2 On the 32 major (mtshan bzang po sum cu rtsa gnyis) and 80 minor marks (dpe byed bzang po brgyad bcu), see Tsepak Rigzin Tibetan-English Dictionary of Buddhist Terminology, pp. 250- 252, 341-343. Dharamsala, HP, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA). 3 These seven views are only mentioned in a note (mchan) to the text, but, except for the seventh one, not explained. Thus, the following summary is based on the TDZ. See TDZ, p. 163f.

Such a ground would lead one to everywhere and nowhere.

3. Assuming it to be determinate would exclude any change. How could ignorance, the cause of suffering, be eliminated under such circumstances?

4. The assumption that it is completely changeable would imply that the result of Buddhahood could again turn into its cause.

5. A ground acceptable as anything could not be ultimate, because one would be confronted with innumerable versions of the ground. 6. Also the assumption that it is variegated on account of its many aspects is denied. How could the many aspects of discursive thinking be acknowledged as the primordial ground? In summary, these six assumptions concerning the ground are similar in one respect:

Holding on to them one falls prey to a one-sided perspective of seeing it as something existent or non-existent. Now, how does the text define the correct view concerning the essential condition of the ground preceding the emergence of the duality of Buddhas and sentient beings? Essence, the first aspect of the original ground (thog ma’i gzhi), marks it as initially pure (ngo bo ka dag), i.e., as empty of being something determinate with clearly delineated characteristics. Nevertheless, its clear nature (rang bzhin gsal ba), the second aspect, is spontaneously perfect (lhun grub

) in its potentiality of self-appearing as what later on is interpreted as samsara or nirvana. Compassion, the third aspect, emphasizes the unity of the two former aspects and specifies the ground as all-pervading (thugs rje kun khyab

). The Rdzogs chen presentation of the ground easily raises critical questions:

Is it not illogical to assume an initially pure ground being present as inner- most being of sentient beings in the face of the fact that they have fallen into samsara? How does it come that they have to purify defilements If their essence has been pure forever? Moreover, why should the result, i.e., final liberation of samsara be obtained after long exertions, if it is already spontaneously perfect at the level of the ground? Rdzogs chen does not deny the fall of sentient beings into samsara, but whatever appears is intuited as mere play of Awareness (rig pa’i rtsal). This play resembles a dream and being ultimately non-existent forever, it is initially pure. The Rdzogs chen point of view that Buddhahood is spontaneously perfect does not make it unnecessary to realize it. However, in this process nothing new is created. Furthermore, realization comes without efforts and often is likened to the awakening out of deep sleep.

The following quotation should shed some further light on the mode of being of the ground4: “The ground with its three aspects is present as inner (nang gsal

), but not as outer, clarity (phyir gsal). It resembles a crystal or a butterlamp in a vessel. It is inseparably clear and empty. Embellished with the innermost Awareness, it is like an egg of a 4 See KDYT II, p. 71. peacock.” This quotation supplies us with important technical terms and suggestive images. First, it is stated that the ground before its arising as samsara or nirvana is present as inner clarity.

The term “inner clarity” hints at its potentiality and at its a temporally unrestricted availability. Outer clarity is not in opposition to inner clarity, but is the inner clarity of the ground which ap- pears now in and as Space and consequently materializes itself increasingly. The different levels of materialization and the reversal of it shall be eluci- dated later on in different contexts. Now, as far as the all-pervading Pristine Cognition of the ground with its three aspects is concerned, it is conceived of as inner clarity and illustrated with a crystal.

The stainless purity and transparency of a crystal suggests its concept-free essence. Furthermore, in the absence of refraction of light, the five lights representing its clear nature do not arise in and as outer clarity, but remain in their potentiality of inner clarity. Finally, its compassion — abiding as subtle unrestricted Awareness ready to arise unceasingly — is equated with the inherent lustre of a crystal. A butterlamp in a vessel pictures the luminosity of the ground as still en- closed in inner clarity, and in order to illustrate the presence of nature and compassion in the initially pure essence of the ground, the picture of an egg of a peacock is given.

The ground before its arising as samsara or nirvana is also defined as “Spontaneously Perfect Precious Sphere” (lhun grub rin po che’i sbubs

) not yet broken through, hence likened to the Youthful-Vase-Body (gzhon nu bum pa’i sku). “Youthfulness” stands here for the emptiness of the ground, being beyond arising and ceasing, and “Vase-Body” indicates that it is a Space ready to manifest as Buddha-Bodies. In other words, the Youthful-Vase-Body is another picture of the emptiness of the ground which has the potential to manifest, and it has to be noted, that it should not be equated with a vessel containing the Buddha-Bodies. Rather, the Buddha-Bodies are present in the ground in the way butter is present in milk potentially. Nevertheless, the ground is ground of everything and arises in dependance on circumstances as samsara or nirvana.

The propriety of the camphor to be beneficial in case of sickness caused by cold and to be harmful in case of sickness caused by heat accurately describes the ambiguity of the ground5: “In the time before the arising of a Buddha on account of his perfect realization and the arising of sentient beings on account of their lack of realization, there is the presence of the Space of Reality (chos dbyings

), an empty Space exposing realm resembling the centre of the bright sky. Furthermore, being bright and unmoving it is also similar to the depth of the ocean, and being clear and unobstructed it bears likeness to the surface of a mirror.

There, in the Sphere of Reality (chos nyid kyi klong na) abides the core, i.e. the fundamental Awareness (gzhi ‘dzin pa’i rig pa), as essence, nature, and compassion.

5 See ZMYT II, p. 103. Like camphor, being neither marked off as samsara or nirvana, it is unobstructed in arising as both. Even though its essence cannot be delineated, it differentiates it- self on account of

circumstances (rkyen). In the ground are neither negative nor positive qualities. How- ever, its mere being the ground of arising of whatever one wishes is the great originary place of all which itself is like the Wish-Fulfilling Gem (yid bzhin nor bu).”

The phrase “there, in the Space of Reality abides the core, i.e., the fundamental Awareness, as essence, nature, and compassion” raises the question about the relationship between Awareness (rig pa) and Pristine Cognition (ye shes)6: “The essence of Pristine Cognition is a non-conceptual consciousness endowed with the self-radiation of the Five Inherent Lights (rang ‘od lnga) which holds onto the nirvanic aspect (of the ground). Furthermore, the essence of Pristine Cognition is an Awareness free of remembering and conceptuality (dran rtog dang bral ba). It is defined as Pristine Cognition, because it knows the meaning (of nirvana).

It is classified into a fundamental Pristine Cognition, namely essence, nature, and compassion, into a Pristine Cognition with five attributes, and into a twofold Pristine Cognition of (all) knowables (shes bya’i ye shes gnyis). It is a consciousness which knows the primordial meaning (ye yi don),the ground as it is. Therefore its is called “Pristine Cognition.” The relationship between Awareness and Pristine Cognition could be described as follows: Awareness is a non-conceptual consciousness which expresses itself as different aspects of Pristine Cognition on account of its realization of the nirvanic aspect of the ground.

Consequently, Pristine Cognition is not merely non-conceptual, but a kind of radiation possessing the potential to arise as the Five Lights of outer clarity. In this context, the white light stands for the Mirror-Like Pristine Cognition (me long lta bu’i ye shes'), the yellow one for the Pristine Cognition of Equality (mnyam nyid kyi ye shes), the red one for the Discriminating Pristine Cognition (so sor rtog pa’i ye shes), the green one for the Accomplishing Pristine Cognition (bya ba grub pa’i ye shes) and the blue one for the Pristine Cognition of the Space of Reality (chos dbyings kyi ye shes). By realizing the five lights of outer clarity as self-appearance of the ground, the nirvanic aspect of it is understood.

On the other hand, not being aware of them as self-appearance is the cause of their condensation into the Five Elementary Forces (‘byung ba lnga'') of samsara. But how are the Five Lights present at the time of the ground preceeding their arising in outer clarity7? “As far as the initial pure essence (of the ground) is concerned, nothing can be established. 6 See ZMYT I, p. 453. 7 See TCZ I, p. 287. Therefore it is not determined as having a definite pattern (ris can) such as the lights and colours of Buddha-Bodies found in outer clarity. Nonetheless, its primordial radiation (ye gdangs) appears in the Space of spontaneously perfect nature as identity of exceedingly subtle appearances of Five Lights, Buddha-Bodies, rays (zer) and drops of light (thig le).

Swirling in (and as) this Space, it abides as Pristine Cognition of inner clarity.” Having clarified the relation between Awareness and Pristine Cognition, the question arises what is meant by conceptuality or conceptual thought (rtog pa). According to Rdzogs chen it is mind (sems) which functions as conceptual thought and which has to be distinguished from the nature of mind (sems nyid).

As should be clear now, Awareness is not something added to the ground, but the ground itself which in its availability of being something conscious is called “nature of mind”. As such it is present before the arising of Pristine Cognition or conceptual thought. Its non-conceptual radiation is Pristine Cognition, spontaneously perfect as Buddha-Realms. Mind, however, initiates deceiving conceptuality and is experienced as painful samsaric existence8: “The essence of mind is samsara as such,(the duality of) the apprehender and the apprehended. Its potential (rtsal) is the apprehender of objects and (the succeeding) attachment to them as belonging to oneself. Its action consists of the production of various samsaric pleasures and pains and its result manifests as endlessness of samsara and evil forms of existence (ngan song).”

The ground as such is intelligent and its split into apprehender and apprehended (gzung ‘dzin) only ensues from the ignorance (ma rig pa) of its initial arising. Having nothing in common with a static entity, it is a self- manifesting process called “singularity” (thig le nyag gcig), defined as the emptiness of the ground in its radiation as self-projecting lighting-up of its unchanging mode of being : “The essence of Self-Awareness (rang rig) is emptiness and the radiation of emptiness is clarity in its unobstructedness.

In spite of its clarity, there is no way of establishing it as a duality (of emptiness and clarity), because its essence is the singularity. On account of the constancy of the ground, one calls the essence of the singularity “circle” (thig). Being unconfined and unrestricted (rgya chad phyogs lhung med pa), one calls it “moment” (le). As its nature can not be established, one calls it “tiny” (nyag) in view of its subtlety. As there is nothing which is not contained within it, one calls it 8 See TCZ II, p. 53. 9 See KDNYT I, p. 33. singular (gcig). It is similar to a root or a seed out of which all of samsara and nirvana spreads.”

In the time before the arising of Buddhas and sentient beings, the ground abides as completely indeterminate inner clarity, symbolized by the Primordial Lord Unchanging Light (gdod ma’i mgon po ‘od mi ‘gyur ba). The anthro- pomorphic representation of the ground as Primordial Lord Unchanging Light indicates that it abides in the heart of sentient beings. “Primordial” as it is, it stays there forever. Moreover, one specifies it as “Unchanging Light“, because of its presence as Three Buddha-Bodies (sku gsum)10:

“Initial purity and spontaneous perfection abide in the ground as inseparableness of appearance and emptiness (snang stong). It is the inner clarity free of dullness and confusion (ma bying ma rmongs) (present) in the middle of the Sphere of the Five Lights of Awareness. Not yet having radiated out, it abides as Vase-Body. At this time nothing is determinated (and as such) it is called by terms like “original general ground” (thog ma’i spyi gzhi), “Primordial Lord Unchanging Light”, or “great ancestor” (mes chen).” The technial terms “Primordial Lord Unchanging Light” (gdod ma’i mgon po ‘od mi ‘gyur ba) or “Original Buddha Unchanging Light” (thog ma’i sangs rgyas ‘od mi ‘gyur ba), “The All-Good-One” (Samantabhadra / Kun tu bzang po) and “Youthful-Vase-Body” (gzhon nu bum pa’i sku) are identical insofar as they are metaphorical expressions describing the ground11:

“The essence (of the ground) is stainless, and the great self-radiation (rang gdangs) of (its) Pristine Cognition is unceasingly clear. It precedes all (other Buddhas) and is endowed with self- appearance of Awareness (rig pa rang snang). Therefore, (it is called) “ Original Buddha Unchanging Light”. The diversity of its qualities is appearing as anything,but in the essence (of the ground) they cannot be distinguished and so all (of its qualities) (are present as) the One Taste (ro gcig pa) in its great non-duality. Therefore, (it is called) “The All-Good-One” (Samantabhadra / Kun tu bzang po). Out of the self-radiation of clear reality itself arises the radiation of pure Pristine Cognition in form of rays (zer gdangs). In this palace of unceasing light, the core, i.e., the Five Buddha-Bodies, (is present in) inner clarity. Therefore, (it is called) “Vase-Body”. And because it is free of old age, (it is called) “Youthful”.

To sum up, while dealing with many rather difficult terms used to describe 10 See KDYT I, p. 442. 11 See ZMYT II, p. 218. the primordial ground or the (fundamental) Awareness one should never forget that according to Rdzogs chen the main point is direct experience of what is meant by it. How would a Rdzogs chen master point out its three main aspects, namely essence, nature, and compassion, to a disciple? Obvi- ously, exemplifying it with a crystal comes in handy12: “The primordial nature of mind, the self-arisen Pristine Cognition itself, abides as essence, nature and compassion. (This) Awareness is shown to be concept-free and empty in its essence.

Therefore, it is similar to a crystal having the qualities of brightness, stainlessness and transparency (zang thal ba). (Without concomitant circumstances), the Five Lights (of a crystal) are not present in outer clarity, but they abide inside in spontaneous perfection. Likewise, the nature is present in the range of Awareness as unceasing light in spontaneous perfection. Therefore, the nature is shown to be clear.

Similar to a crystal being inseparably (dbyer med) bright and pure (dkar po), compassion is shown to arise unceasingly (as inseparable unity of essence and nature). Although these three qualities (of a crystal) can be distinguished, ultimately, in their essence, they are not different. Likewise, the Awareness being empty, clear and unceasing, is shown to be an inseparable unity of essence, nature, and compassion.” — The Second Theme — The assessment of the origin of delusion in the ground as defined in the First Theme Up to this point, the text has treated the mode of being of the ground before its arising as samsara and nirvana. The Second Theme now elucidates how it actually comes forth as samsara on account of the three aspects of ignorance (ma rig gsum).

But its initial stirring, the first moments of the inner light transforming itself into the outer one, are not treated in the text. Neither is the mode of (nirvanic) liberation of Samantabhadra (Kun tu bzang po’i grol tshul) dealt with, because the text explicitly is intended as a manual for adepts of Rdzogs chen practice (lam rjes su 'dzin pa'i gang zag). Consequently, information concerning aspects of rather theoretical concern such as the ones mentioned above have to be drawn from other sources. The whole process of the self-appearance (rang snang) begins with a first phase within inner clarity, called “Spontaneously Perfect Precious Sphere” (lhun grub rin po che’i sbubs) followed by a second phase, circumscribed by terms such as “the Spontaneously Perfect Appearance” (lhun grub kyi snang ba) or “the abiding in the outwardly clear appearance of the light-sphere of Pristine Cognition” (ye shes ‘od kyi sbubs phyir gsal gyi snang ba la gnas pa)13: 12 See KDYT III, p. 171. 13 See KDYT II , p. 98.

“Out of the Precious Spontaneous Perfection (of) the inner clarity (of) the primordial ground, compassion moves (as) Pristine Cognition of Awareness (rig pa’i ye shes) in its rudimentary knowing (rig tsam) (driven by) the wind of life-force and its four branches which becomes the power of (its) discriminative awareness14.

Thereby (compassion) arises outwardly together with the lustre of the spontaneously perfect inner nature. At this time (there is) the so called “abiding in the outwardly clearappearance of the light-sphere of Pristine Cognition” (which arises) after the manifestation of the inner clarity of the Spontane- ously Perfect Precious Sphere (with its) presencing of (compassion and nature) as Buddha-Body and Pristine Cognition in the sphere of the empty essence. Even though the outwardly arising aspect of ac- tive compassion does not (yet) proliferate as discursive thought, it moves away from the ground on account of which it is called “lame Awareness”.

Moreover, this appearance is called “borderline of light and darkness”, because it manifests out of the primordial mode of being in outer clarity, but is presencing (itself) in a intermediate phase lacking the error of a sentient being (caused by) ignorance.“ The term “borderline of light and darkness” (mun snang gnyis kyi mtshams) illustrates clearly the still undetermined being of the now outwardly ap- pearing ground being available as such on account of its immediately preceding transformation into the Spontaneously Perfect Precious Sphere, a sphere still resting in inner clarity.

Neither realized as self-appearance by the Buddha Samantabhadra nor ignored as such by sentient beings, the subsequent transformation is called “abiding in the outwardly clear appearance of the light-sphere of Pristine Cognition”. The outwardly arising aspect of compassion is termed “lame Awareness”, because it initiates the movement away from the ground which implies the danger of going astray into sam- sara.

Another passage in the text quoted above brings into prominence the cognitive aspect of the first stirring of the ground : “From (the point of view of) the indestructible vajra (pprdo rje) which I am, there is no outer frame of reference (dmigs pa). (However,) the inwardly present intention (yid) (now) moves and begins to think (rig rig) on account of which (the outer arisal of the ground) is set in motion by means of the wind (rlung) (which originates) from the causal inseparability (of the aspects of the ground). Out of the seed of one-pointed non-conceptuality the propelling Pristine Cognition (‘phen pa’i ye shes) itself is generated. (Thus, the ground) enters the womb which is a borderline of light and darkness.” 14 A slightly different set of five winds (rlung lnga) is presented in the Third Theme. 15 See BMNYT II, p. 591.

The role played by the propelling Pristine Cognition and the wind is elucidated in the following quotation16: “Out of the range which is an abiding with one-pointed non- conceptuality in the intrinsic reality (rang bzhin) of the essence, nature, and compassion of the primordial mode (representing) the primordial mode of being in its great initial purity and its inner clarity, all aspects of the Spontaneously Perfect Appearance of the Ground (gzhi snang lhun grub) arise. Moreover, this propelling Pristine Cognition, being compassion it- self, abides in the range of the Clear Light (‘od gsal) (of) the Spontaneously Perfect Ground as extremely subtle and impartial discrimi- native awareness (of) the inner clarity of Pristine Cognition of Awareness (pprig pa’i ye shes[[) or as embodiment of the core (ppsnying po’i bdag nyid can[[). (Abiding as such) the upward-moving (wind) (gyen du rgyu) (functions as) horse of discriminative awareness, the downward- clearing (wind) (thur du sel) as (inner) glow of the rays of discriminative awareness, the fire accompanying (wind) (me mnyam) (as) carrier of the strength of ripening, and the pervading (wind) (khyab byed) (as) carrier of the strength of completion.

The nature of the five winds, four of them being branches (of the main one), is such that they dwell in their function of being the core or the ground of arising of the totality of The Spontaneously Perfect Appearance (lhun grub kyi snang ba) as unceasing radiation.” To sum up, the inwardly present intention is a kind of rudimentary know- ing, is compassion itself which begins to move into outer clarity. The techni- cal term for this feature of compassion is “propelling Pristine Cognition”.

In its function as subtle discriminative awareness it is forever present in the Clear Light of the ground and with the help of its accompanying wind the outer wall of the Youtful-Vase-Body is finally broken through whereupon a second phase, the so called “Spontaneously Perfect Appearance” (lhun grub kyi snang ba) sets in. This phase marks the actual beginning of the outer arising of the ground and it consists of Four Meditation-Days (bsam gtan zhag bzhi), four sub- phases of increasing concreteness in outer clarity17:

1. The Spontaneously Perfect Precious Mode of Being (lhun grub rin po che’i gnas lugs),

2. the Great Appearance of the Ground (gzhi snang chen po),

3. the Appearance of the sambhogakāya (longs sku’i snang ba), and

4. the Appearance of the nirmaṇakāya (sprul sku’i snang ba). 1.

The Spontaneously Perfect Precious Mode is also termed “uncertain ground” (gzhi ma nges pa), “spontaneous perfection” (lhun grub) or “ground 16 See BMYT II, p. 50. 17 An exposition of the Four Meditation-Days (bsam gtan zhag bzhi) can be found in the KDYT II, p. 100. arising as variety“ (gzhi sna tshogs su ‘char ba), and it exhibits eight aspects, namely Six Modes of Arising (‘char tshul drug) and Two Doors (sgo gnyis):

1. Arising as compassion (thugs rje ltar),

2. as light (‘od ltar),

3. as Buddha-Bodies (sku ltar),

4. as Pristine Cognition (ye shes ltar),

5. as non-duality (gnyis med ltar), and

6. as liberation from extremes (mtha’ grol ltar).

1. The door of the complete Buddhahood of Samantabhadra (Kun tu bzang po mngon par byang chub pa’i sgo), and

2. the door of the going astray of sentient beings into samsara (sems can ‘khor bar ‘khrul pa’i sgo). In the following quotation one finds a short but clear explanation of these eight aspects of the Spontaneously Perfect Precious Mode of Being : “With regard to the Six Modes of Arising: As (the ground) arises as compassion, compassion for sentient beings arises. As it arises as light, the worlds are pervaded by rays of light. As it arises as Buddha-Body, all appearances arise as heaps of the Five Buddha-Families (rigs lnga).

As it arises as Pristine Cognition, the pure Buddha realms are clearly visible in immediate perception. As it arises as non-duality, there is an abiding in a non-discursive absorption. As it arises as freedom from extremes, there is a momentary abiding in the nature of reality (chos nyid). With regard to The Two Doors: When this appearance of Pristine Cognition is understood as self- appearance, the door of the complete Buddhahood of Samantabhadra in the primordial ground (opens up), and when it is not understood as such, the door of the going astray of sentient beings into samsara (opens up).” Before investigating The Two Doors in detail the three other sub-phases of the Spontaneously Perfect Appearance shall be discussed briefly in order to have an overview of the whole process of the actual outer arising of the ground.

2. The second sub-phase, termed “theGreat Appearance of the Ground” (gzhi snang chen po) arises immediately after the conclusion of the first one. It exhibits a variety of rainbow-like appearances such as the Banners of Pris- tine Cognition (ye shes kyi snam bu)19: “Not having recognized the (first) appearance as self- appear- ance, it comes to an end. On the second day there is the so called “Great Appearance of the 18 See KDYT II, p. 102. 19 See KDYT II, p. 103. Ground”.

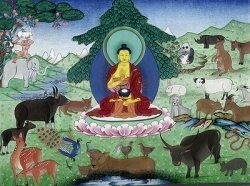

(This) appearance of the Five-Coloured Banners of Pristine Cog- nition resembles a stratification of the rainbow-spectrum in the ten directions. In(side) it, appearances of Pristine Cognition, which are embel- lished with five-coloured heaps, arise everywhere. It is also said that some (sentient beings) have attained liberation in the primordial ground on account of having recognized this ap- pearance (for what it is).” 3. In the same text we read about the appearance of the sambhogakāya (longs sku’i snang ba)20: “Concerning the third one: After the conclusion of the former one, there is in the third day, the so called “Appearance Of the sambhoga-kāya”. In the all-encompassing appearance of the Clear Light, heaps of the (Five) male-female Buddha-Families (rigs lnga) shining in their Major and Minor Marks (mtshan dang dpe byed) light up...” As it were, an explanation of the Five Buddha-Families (rigs lnga), is based here on the view of Rdzogs chen with its emphasis on a fundamental Awareness (rig pa)21: “The appearance of compassion, i.e., the Pristine Cognition of Awareness, as totality of (perceptible) forms is the Body of Vairocana (Rnam par snang mdzad kyi sku).

This Pristine Cognition of Awareness - when not moved by the wind of conceptuality - is the Body of Akṣobhya (Mi bskyod pa rdo rje’i sku). The coming of everything needed out of the realization of Awareness which is like a wishfulfilling gem, is the Body of Ratnasambhāva (Rin chen ‘byung ldan gyi sku). The unlimited dwelling of this Awareness in the appearance of boundless light is the Body of Amitābha (Snang ba mtha’ yas kyi sku). The great self-arising of the play of Awareness (rig rtsal) of un- ceasing compassion is the Body of Amoghasiddhi (don yod grub pa’i sku).” 4. The fourth sub-phase, the Appearance of the nirmaṇakāya (sprul sku’i snang ba), exihibits three levels: 1. The actual nirmaṇakāya (rang bzhin sprul sku), 2. the Six Sages (thub pa drug), and 3. the nirmaṇakāya with Various Forms (sna tshogs sprul pa).

1. The Actual nirmaṇakāya consists of the Five Buddha-Families which ap- pear now in their semi-concrete form as teacher of Bodhisattvas of the Tenth 20 See KDYT II, p. 104. 21 See KDYT II, p. 220. Level (sa bcu pa)22. This appearance is termed “semi-concrete“, because it presents itself half- way between the more subtle appearance of the sambhogakāya and the two other levels of the nirmaṇakāya which are more concrete than it. 2. The Six Sages represent six aspects of Buddha arising in the six samsaric realms of gods, anti-gods, human beings, animals, hungry ghosts and hell- beings as Brgya byin, Thags bzang, Shā kya thub pa, Seng ge rab brtan, Kha ‘bar bde ba, and A lba glang mgo, respectively. 3. As the name implies, the nirmaṇakāya with various forms stands for an in- determinate variety of possible manifestations of the nirmaṇakāya. The fol- lowing quotation affords a glimpse of this fourth sub-phase of the “Spontaneously Per

fect Appearance”23: “Out of the (appearance of the sambhogakāya) (arise) the pure realms (zhing) of the Five Buddha-Families (of) the actual nirmaṇakāya , namely, ‘Og min , Mngon dga’, Rin chen yongs gangs , Padma brtsegs , and Las rab grub pa. There, the teacher, being the Five Buddha-Families, presents him- self to his retinues of the Tenth Level in his perfect mirror(like) form during the three times. The obscurations of the Tenth Level are cleared by means of (his) swirling light-rays. Thus, he accomplishes the charismatic activity of placing (his reti- nues on the level) “Light Everywhere”.

This pure realm appears (only) to the assemblage of (his) pure victorious sons. (Originating) from light-rays emitted from (his) mouth, Brgya byin, Thags bzang, Shā kya thub pa, Seng ge rab brtan, Kha ‘bar bde ba, and A lba glang mgo benefit the impure (sentient beings dwelling) in the worlds of gods, anti-gods, human beings, animals, hungry ghosts and hell-beings in forms adopted to them, thereby (still) relying on the peaceful space (zhi ba’i dbyings). Thus, the nirmaṇakāya with various forms accomplishes the charismatic activity of ultimately certain excellence after having effected an abiding in happiness, ease and joy (by means of things) such as skilled craft, birth as living being, ponds, bridges, lotus flowers, wishfulfilling trees, drugs, precious stones and lights.

After the extinction of beings to be tamed the taming (Buddha) dissolves in (peaceful) space.” After having shortly elucidated the four increasingly concrete sub-phases of the “Spontaneously Perfect Appearance”, it is necessary to return to the point where Samantabhadra (Kun tu bzang po) gained liberation and where sentient beings went astray in order to discuss the Second Theme of the Tshig don bcu gcig pa , namely ignorance.

As we know, the Two Doors related 22 On the Ten Bodhisattva Levels (sa bcu), see Guenther, Herbert V. 1975. Kindly Bent to Ease Us: The Trilogy of Finding Comfort and Ease, Part One, pp. 241-244. Emeryville, California, Dharma. 23 See the text Sems nyid rang grol, p. 32. In Rang grol skor gsum. Gangtok/ Sikkim. Dodrub chen Rinpoche Edition. to liberation and ignorance arise in the first sub-phase. Two subsequent moments of realization are required to open the Door of the Complete Buddhahood of Samantabhadra24: “Out of the presence of the essence, nature, and compassion (of) the primordial ground in inner clarity, the Pristine Cognition of Awareness has moved with (the help of) the four(fold) life-wind which has provided (its) horse. Together with the Awareness (of) compassion, which slightly has arisen outside, the pure realms of the Buddha-Bodies and Pristine Cognition (originating) from the nature have lit up like the rising sun. In a first moment an understanding has arisen, because compas- sion has clearly (lbal gyis) recognized (this lighting up) as inner ra- diation (mdangs) arising outwardly in its self-appearance.

Afterwards, the overestimated nirvanic vision (of) outwardly clear Buddha-Bodies and (of) appearances of the Clear Light, and the undervalued vision, i.e., the door of samsara, possessing the seeds of the impurely arising ground of the six kinds of sentient beings, namely “A”, “NRI”, “PRE” “DU, “SU”, “HRI”, are naturally purified and neutralized (rang log).

Being free of them, the whole of outer clarity has been inwardly absorbed in a second moment. Present as great inner clarity which has remained without change as it has been before, the ground has ripened into the result. The result (is) the capture of the stronghold (of the ground), and like the fruit of the pomegranate tree (which does not bear seeds), it abides without falling back into the cause (of error).” The understanding of Samantabhadra is qualified by three self-arisen as- pects of teaching (rang byung gi chos gsum)25:

“In short, after having effected a difference of his understanding in one single moment, the primordial Samantabhadra attained Buddhahood. As it is written in the Tantra of the Magical Net (Sgyu ‘phrul drwa ba): The difference effected in one single moment. Buddhahood perfected in one single moment. Samantabhadra who has been liberated in this way posseses three self-arisen aspects of teaching: The quintessential teaching which has not originated from an oral transmission of teaching (lung), the Buddhahood which has not originated from mind (sems), and the result which has not originated from a cause. Concerning the first (aspect): Buddhahood has been attained on account of the self-arisal of self-existing (rang byung) realization without a teacher giving an oral transmission. 24 See KDYT II, p. 109. 25 See KDYT II, p. 118.

Concerning the second one: Because of not having gone astray into samsara, enlightenment has been attained by knowing the Self- Liberation of Awareness which is not (affected by) the Eight Collec- tions (tshogs brgyad) together with their all-ground (kun gzhi)26. Concerning the third one: Having seen the mode of being of the ground, the three (aspects of) Awareness have been attained without even a slight accumulation of virtue such as (exemplified by) the Two Collections (tshogs gnyis)27.

Thus, in the reach of the ground which is as it is, (these three as- pects) are in themselves spontaneously perfect forever.” In this quotation we met with the controversial statement that Samanta- bhadra (Kun tu bzang po) has attained Buddhahood without having accu- mulated the Two Collections. However, this statement has to be understood in a qualified sense28: “Although (the statement) “Samantabhadra has attained Buddha- hood on the ground without even a slight accumulation of virtue” is well known, nevertheless, (it is not exactly correct). If it is scrutinized, (it becomes evident) that the recognition of one’s essence (rang ngo) is a ocean of self-arisen stainless virtue. (This recognition) is the forever present perfection of the great ac- cumulation and the forever present conquest of obscurations (sgrib) by virtue of the purification of neutral ignorance (lung ma bstan gyi ma rig pa).” The term “ignorance” (ma rig pa) leads us to the second door of the Sponta- neously Perfect Precious Mode Of Being (lhun grub rin po che’i gnas lugs), namely the door of the going astray of sentient beings into samsara (sems can ‘khor bar ‘khrul pa’i sgo). Actually, the Second Theme of the Tshig don bcu gcig pa ,focuses entirely on a set of threefold ignorance as cause, and a concomi- tant set of fourfold conditions: 1.

The ignorance of undivided identity (bdag nyid gcig pa’i ma rig pa), 2. the simultaneously produced ignorance (lhan cig skyes pa’i ma rig pa), and 3. the conceptual ignorance (kun tu brtags pa’i ma rig pa). 1. The first one is called “ignorance of undivided identity“, because basi- cally, ignorance does not differ from Awareness (rig pa). Thus, it simply rep- resents the lack of such an understanding. 26 On the all-ground (kun gzhi) and the Eight Collections (tshogs brgyad), i.e., eye consciousness (mig gi rnam shes), ear consciousness (rna ba'i rnam shes), nose consciousness (sna'i gi rnam shes), tongue consciousness (lce'i rnam shes), body consciousness (lus kyi rnam shes), mental consciousness (yid kyi rnam shes), emotive consciousness (nyon yid kyi rnam shes), and consciousness of the all-ground (kun gzhi rnam shes), see Thondup Tulku 1989. Buddha Mind , p. 216.

Ithaca, New York, Snow Lion. 27 On the Two Collections (tshogs gnyis), see H.V. Guenther 1984. Matrix of Mystery, p. 214, no. 16. Shambala, Boulder & London. 28 See TCZ I, p. 311. 2. The second one points to the assumption that Awareness and ignorance arise simultanously (lhan cig skyes pa) in this first outer stirring of the ground. Another interpretation of the term “simultaneous” suggests the synchronism of the first ignorance which stands for the subject-side, i.e., consciousness, and the second one which arises in this phase of self- appearance as its object in the form of the Five lights (‘od lnga). 3. The third one comes after the two kinds of ignorance mentioned above and represents the conceptual misapprehension of the self-appearance of the ground. Ignorance is accompanied by four conditions (rkyen bzhi) which arise together with it: 1. The causal condition (rgyu’i rkyen), i.e., the threefold ignorance itself.

2. The object-condition (dmigs pa’i rkyen), i.e., the outer arising of the Five Lights (‘od lnga). 3. The dominant condition (bdag po’i rkyen), i.e., the apprehension of these lights by the “Self” (bdag). 4. The simultaneous condition (mtshungs pa’i rkyen) finally, expresses the synchronism of the three conditions mentioned above. Thus, the text of the Second Theme runs as follows: “The essence, the Pristine Cognition (of) Awareness initiates the cause of the ground of error (‘khrul gzhi) and changes into the igno- rance of undivided identity (bdag nyid gcig pa’i ma rig pa).

The nature brings forth the condition of error whereby the pro- pelling wind (‘phen pa’i rlung) arises. Lighting up as colours it turns into the simultaneously produced ignorance (lhan cig skyes pa’i ma rig pa). The compassion produces the result of error in that the Pristine Cognition dwelling in the ground (gzhi gnas kyi ye shes) comes to be the conceptual ignorance (kun tu brtags pa’i ma rig pa). Now, not knowing that Awareness and ignorance are like front and back of one hand, the ignorance dependent on Awareness, (be- ing) the error relying on the lack of error (ma ’khrul pa), (arises) . As one is labelling (the initial appearance of the ground), it arises as (object of) names.

Thus, by designating it by various names such as “this is the Pris- tine Cognition of Awareness and this is ignorance and error”, it turns into the conceptual ignorance (kun tu brtags pa’i ma rig pa). Conceiving of it as object and subject - being similar to the (re- flected) figure of a man (apprehended by him) - produces the cause of error, namely the three kinds of ignorance called “causal condi- tion” (rgyu’i rkyen). The so called object-condition (dmigs pa’i rkyen) is arising as vari- ous mental images of objects, thus, it is similar to (reflections of) a mirror, and the “I” and “Self”, the variety of apprehending and ap- prehended (gzung ‘dzin), (represents) the dominant condition (bdag po’i rkyen).

Since these three conditions (arise) at the same time, (the fourth) emplified by the nameless turning into names. Thus, going astray by not knowing the essence, the places of sentient beings, the sense or- gans, and the passions manifest beyond measure.” A presentation of the formation of the life-horizons of sentient beings is out of the scope of this work. The salient feature of it, however, is, as it were, the increasing materialization of light, light understood as inherently intelligent. Remarkable in this context is the fact that the ensuing concretization of the appearance of the ground into the different life-horizons of sentient beings is viewed only as an incidental process triggered by ignorance. How this pro- cess leads to a hardening of the Five Lights into the Five Elementary Forces (‘byung ba lnga) — the whole process being a misapprehension of the poten- tiality of Prisitine Cognition (ye shes kyi rtsal) — is explained in the following quotation29: “Concerning the reason of the presence of the Five Outer Ele- mentary Forces:

First, on account of the arising of the potentiality of Pristine Cognition in (its) ever non-existent emptiness, the Five Lights have arisen. On account of unceasing Awareness (present) in this (potential- ity), a (subjective) apprehending of the Five Lights has arisen. Holding them as real (dngos ‘dzin) is called “wind”. Ultimately, it is the potentiality of Awareness. In this (context) the red inner radiation (mdangs) is the Discrimi- nating Pristine Cognition (so sor rtog pa’i ye shes). Going astray on account of holding this (red light) as real, the red fire has arisen. In this (red fire) has arisen the warmth of the wind (which is) the potentiality of Awareness. Moreover, the Pristine Cognition of Equality (mnyam nyid kyi ye shes) has lit up as yellow light. On account of apprehending it, the earth has arisen. On account of apprehending the arising of the white light (of) the Mirror-Like Pristine Cognition (me long lta bu’i ye shes), the white water has arisen. On account of apprehending the arising of the green light of the Accomplishing Pristine Cognition (bya grub kyi ye shes), the air has arisen. Concerning the Elementary Force space:

It abides since the pri- mordial beginning together with Pristine Cognition, and even in the end, it is free of shifting and changing (‘pho ‘gyur med).” 29 See KDNYT II, p. 71. — The Third Theme — The presence of the core or seed of perfect Buddhahood in sentient beings despite of the already arisen delusion The mode of abiding of the Buddha-Essence (snying po) in sentient beings is frequently treated in Rdzogs chen texts by means of general and specific ex- planations. As there is only a specific explanation to be found in our text, we have to take recourse to the TDZ30 in order to make available a general explanation of the third theme.

There one finds quotations from tantric as well as from sūtric sources. According to the Rdzogs chen Tantra Rdo rje sems dpa’ snying gi me long , the Buddha-Essence exists in sentient beings of the Three Realms (‘jig rten gyi khams gsum) in the same way as oil is present in a sesame seed. Similar descriptions can also be found in Rdzogs chen Tantras like Nor bu ‘phra bkod and Sgra thal ‘gyur. Quotations from other Tantras such as the famous Kye rdo rje (Hevajratantra) are brought up in order to prove the correctness of the assumption of a Buddha-Essence: “In the body (of all sentient beings) the great Pristine Cognition is present. (It is) the perfect abandonment of all discursive thoughts.

It pervades all things. It is present in the body, but has not taken birth from it.” As a sūtric source, the text ‘Mya ngan las ‘das pa chen po’i mdo (Māhapari- nirvānasūtra) is quoted. Here, the Buddha-Essence is compared with a gol- den treasure hidden in a poor house whereof the owner is ignorant. The usual doubts concerning the ultimately valid (nges don) presence of the Bud- dha-Essence are based on the supposition that the nature of mind (sems nyid), that is to say emptiness itself (stong pa nyid), does not exhibit Buddha- Qualities (yon tan) such as the Major and Minor Marks (mtshan dpe) or the Ten Powers of a Buddha (stobs bcu).

In this context, the opponents of an ulti- mately valid Buddha-Essence argue that all texts of the Shes rab pha rol tu phyin pa (Prajñāpāramitā) liken the selfless nature of phenomena (gnas lugs bdag med) to the empty sky. Accordingly, the Buddha-Essence conceived of as possessing manifold positive qualities is merely accepted as a provisional- ly valid (drang don) concept. Without defining it as such, it would be iden- tical with the self of the Non-Buddhists (mu stegs pa). However, Klong chen rab ‘byams insists on the ultimate validity of the Buddha-Essence. In his view, the fact that Buddha Sakyamuni has finally turned a third wheel (‘khor lo gsum pa)31 focusing on the Buddha-Essence, is in evidence of the correct- ness of not classifying the second one with its emphasis on exclusive empti- ness (stong nyid rkyang pa) as ultimately valid. Exclusive emptiness is viewed upon as intended for beginners not yet being able to free themseves from an attachment to a self (bdag tu ‘dzin pa).

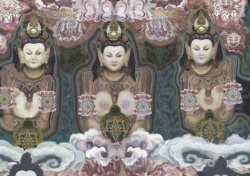

Klong chen rab ‘byams does not admit the objection that the Buddha-Essence exhibiting Buddha-Qualities is identi- cal with the self of the heretics, because he does not deny its emptiness, that is to say, in his line of thought it does not represent a specifically 30 The following summary is based on the TDZ, p. 216-221. 31 On the Three Turnings of the Wheel ('khor lo gsum) see Snellgrove, David L. 1987. Indo- Tibetan Buddhism, p. 79f. Boston, Shambala Publications. be incorrect to conceive of it as something exclusively eternal. Last but not least, it can be revealed by means of quintessential instructions of a teacher, hence, it is freely accessible. According to the specific explanation to be found in the Third Theme of the text, the core or seed of perfect Buddhahood presents itself in the body of sentient beings in the form of six different sets, each exhibiting five aspects: “It is said that the core of perfect Buddhahood pervades all sen- tient beings, because the Pristine Cognition of Awareness resides in the body of a sentient being in fivefold form, namely as Five Buddha- Bodies (sku lnga), Five Buddha-Families (rigs lnga), Five Aspects of Pristine Cognition (ye shes lnga), Five Winds (rlung lnga), Five Aspects of Discriminative Awareness (shes rab lnga), and as Five Lights (‘od lnga).

It is also said that one’s own body is Vajra-Buddha(hood), that Buddhahood resides in one’s own body and that it cannot be re- vealed somewhere else. Therefore, concerning the Pristine Cognition of Awareness itself, as it appears (in and as cognition of) forms of objects (rnam pa‘i yul), it is the Self- Arisen Body of Making Appear Objects in Their Dis- tinctiveness (rnam par snang mdzad sku / Vairocana), not to be searched for elsewhere. “Vajra” means that insofar as the unchanging essence of Aware- ness is not shaken by conceptual thoughts, Awareness itself has arisen as the Unchanging Vajra-Body (Rdo rje mi ‘gyur ba’i sku / Akṣo- bhya). Furthermore, since unfathomable doors of expanding qualities such as the the Vision of Increasing Experiences (nyams snang gong ‘phel) have arisen from Pristine Cognition of Awareness, it has arisen itself as (the Buddha) Source of Preciousness (Rin chen'byung ldan / Ratnasambhāva).

Since the aspect of clarity (gsal cha) of Awareness has appeared as limitless light-rays, it has arisen itself as (the Buddha) Limitless Illu- mination (Snang ba mtha' yas / Amitābha) (and) Unfathomable Light ('Od dpag med). Furthermore, since the Pristine Cognition of Awareness itself is present in the essence of Pristine Cognition, and since accomplish- ment is certain by having made an experience of it, it has arisen itself as (the Buddha) Accomplishment of Meaning (Don yod grub pa / Amoghasiddhi). Thus, the Rdzogs chen adept does not have to search for the tute- lary deity (yi dam gyi lha) elsewhere and he does not have to contem- plate it. Therefore, he is free from debilitating disease. Furthermore, one’s own nature of mind has arisen as Five Bud- dha-Families (rigs lnga): Since the Awareness has gone into the un- born Space (skye med kyi dbyings) and has been absorbed there with- out its potential being obstructed (rtsal ‘gag med) thereby , it is the Buddha-Family of the One Who has Gone to Suchness (de bzhin gshegs pa’i rigs).

Since its essence (can) not be changed by conditions, it is the Vajra-Buddha-Family (rdo rje rigs). Since all Buddha-Qualities are present in it in self- perfection, it is the Buddha-Family of Preciousness (rin po che’i rigs) and since its es- sence (can)not be defiled by faults, it is the Buddha-Family of Lotus (padma’i rigs). Since everything is present as action of miraculous display (cho ‘phrul) of Awareness, it is the Buddha- Family of Accomplished Ac- tion (las kyi rigs). Furthermore, Awareness itself is also present as Five Aspects of Pristine Cognition: Since everything, religious activities (chos spyod) and (objects) being existent by way of their own characteristics (rang gi mtshan nyid) or being qualified by form (gzugs can), manifest clearly (gsal ba) out of the range of Awareness, it is the mirror-like Pristine Cognition. Since the variety of things (chos can) are equal in the expanse of the unborn nature of appearances, it is the Pristine Cognition of equality. Since out of its range all Buddha-Qualities manifest clearly with- out their aspects becoming mixed up, it is the fully disciminating Pristine Cognition. Furthermore, it is not necessary to realize it by means of exertion. Since it is present forever (ye nas) in spontaneously accomplished self-clarity, it is the accomplishing Pristine Cognition. However, all these (aspects of Pristine Cognition) (can)not be separated.

Since they (exhibit) One Taste (ro gcig) in the reality of appear- ances (which is) emptiness itself, (Awareness) is the Pristine Cogni- tion of reality. One’s own Awareness itself has also arisen as Five Lights: Since Awareness itself is not defiled by karma (las) and afflictions (nyon mongs), it also appears as white (light). Because (its) Buddha-Qualities are perfect, it also appears as yel- low (light). Since everything is under control of Awareness, it appears as red (light). Since it is beyond exertion, it is green (light). Since its essence is not changing despite its arising in diversity, it appears as blue (light). Awareness itself has also arisen as Five Winds: Because it brings down the warmth of the Pristine Cognition of Awareness, it is called “the wind that is accompanied by fire” (me dang mnyam pa’i rlung).

Because it upholds the life-force of the whole of samsara and nirvana, it is the wind that upholds the life-force (srog ‘dzin gyi rlung). Since it distinguishes (things) such as sense-organs, objects and colours it is the wind that separates the pure from the refuse (dwangs snyigs ‘byed pa’i rlung). Since it pervades the whole of samsara and nirvana, it is the per- vading wind (khyab byed kyi rlung). Since it drives one to the level of nirvana (mya ngang las ‘das pa), it Discriminative Awareness: Since it has become the ground of arising of the whole of samsara and nirvana, it is the discriminative aware- ness that does not distinguish (‘phyad pa med pa’i shes rab). Since it is not beyond the range of one’s own Awareness, it is the discriminative awareness that holds together (sdud par byed pa’i shes rab).

Since it has arisen as the essence of everything, it is the discrimi- native awareness that pervades (khyab par byed pa’i shes rab). Since it acts in (its own) Space through recourse to the wind of Pristine Cognition (ye shes kyi rlung), it is the discriminative aware- ness that moves (skyod pa’i shes rab). Since it clears misconceptions concerning both, samsara and nir- vana, it is present as the discriminative awareness that clears miscon- ceptions (sgro ‘dogs gcod pa’i shes rab). Thus, since there is nothing else than Awareness itself, it is called “self-arisen Pristine Cognition” (rang byung gi ye shes). Furthermore, since it is present (gnas pa) in its essence as Buddha- Body, it is the dharmakāya itself during the time of meditation (mnyam gzhag). During the time of the non-duality of meditation and post- meditation it is the sambhogakāya, and during the time of post- meditation (rjes thob) it is the nirmaṇakāya.

Since its nature is clearly manifest as light, it abides in the ground as self-clarity and its sign clearly manifests as lamps. The aspect of its compassion is present as Pristine Cognition. Thus, since it is present as ground of everything, it is not neces- sary to search for Buddha (elsewhere), being the proof that one’s own mind is Buddha forever.” In what way the five aspects of essence, nature, and compassion are present in sentient beings is elucidated in the following quotation32: “Sixth, as to the five aspects of essence, nature, and compassion: The meaning of these (five aspects) (can) be subsumed under the Three Buddha-Bodies of the Pristine Cognition which is present in the ground (gzhi gnas kyi ye shes). The five (aspects of) the essence are correlated to the Five Buddha- Bodies of the ground of arising, and the five (aspects of) the nature are correlated to the appearance of Five Lights. The five (aspects of) compassion are correlated to the Five Aspects of Pristine Cognition.

They are the compassion of the natural force at the level of Buddhahood (sangs rgyas kyi sar rang bzhin shugs kyi thugs rje), the compassion that contacts conditions and objects (rkyen yul dang ‘phrad pa’i thugs rje), the compassion (caused by) exhortation and supplica- tion (bskul zhing gsol ba btab pa’i thugs rje), the compassion of various activities (mdzad pa sna tshogs kyi thugs rje), and the compassionthat 32 See TDZ, p. 226. does not change (its attitude concerning) those to be tamed (gdul bya mi ‘gyur ba’i thugs rje). These five (aspects of compassion) have arisen out of the sponta- neously accomplished aspect, being the aspect of the ground of aris- ing (of everything) present now in the Pristine Cognition of Aware- ness.“ It has to be noted that all these sets exhibiting five aspects are merely poten- tially at disposal in the ground.

As mentioned above, butter potentially pre- sent in milk serves as an example for their mode of being during the time before the arising of the ground as anything. Thus, according to Klong chen rab ‘byams one has to distinguish clearly between the mode of being of the core or seed of perfect Buddhahood during the time of the ground and the time of the result. — The Fourth Theme — The precise location of the seed or essence of perfect Buddhahood “Moreover, the Pristine Cognition of Awareness abides in The Precious Palace of the Heart (tsitta rin po che'i gzhal yas khang) being situated in the middle of the body. It abides there as the Peaceful Buddha-Body (zhi ba’i sku) which has approximately the size of a mustard- seed with eyes in propor- tion to it. It is described as “mustard-seed” on account of being subtle and difficult to realize.

“Eyes in proportion to it” means that vast visions of Pristine Cog- nition (arise) in dependence upon a subtle practice (nyams len). Furthermore, the abiding of the essence (of Pristine Cognition of Awareness) as Buddha-Body is similar to a Vase-Body (bum sku). The abiding of its nature as light resembles a butterlamp inside a vase (bum nang gi mar me), and the door of the lamps lights up un- ceasingly on account of the abiding of (its) compassion as light-rays (‘od zer). Incidentally, ignorance, passion, karma, karmic propensities (bag chags), discursive thought (rnam par rtog pa), etc., abide in the lungs by virtue of the power of karmic wind (las rlung).” According to Rdzogs chen thought, the Pristine Cognition of Awareness, de- fined here as seed or essence of perfect Buddhahood, pervades the whole body of sentient beings, but its focal point, being localized in the heart, is called “the Precious Palace of the Heart”. Even though only the heart is mentioned in our text, in general, one can distinguish four such focal points:

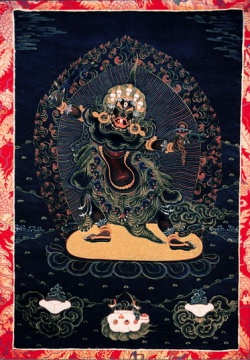

1. The Precious Palace of the Heart, (tsitta rin po che'i gzhal yas khang), 2. the Palace of the Channels Initating Movement (’gyu byed rtsa yi gzhal yas), 3. the Palace of the Skull Mansion (dung khang bhandha’i gzhal yas), and 4. the Palace of the Eyes Initiating Seeing (lta byed mig gi gzhal yas)33. The Palace of the Channels Initating Movement and the Palace of the Eyes Initiating Seeing are dealt with in the context of the Sixth. As far as the focal points of the heart and the skull are concerned, one can find numerous descriptions of them. For instance, the Precious Palace of the Heart is circumscribed as the In- tention of the Closed Sphere of Samantabhadra (kun tu bzang po ga’u kha sbyor gyi dgongs pa)34. In the middle of this sphere, the Forty-Two Peaceful Buddha-Bodies (zhi ba’i sku), headed by the Five Buddha-Families, are pre- sent in the size of a mustard-seed, covered by five-coloured light.

In the skull reside the Fifty-Eight Wrathful Buddha-Bodies (khro bo’i sku) as radiation of the Pristine Cognition (ye shes kyi gdangs) of the focal point of the heart. Here, the Five Buddha-Families manifest themselves as the Five Herukas, namely as Vajra Heruka (Badzra he ru ka), Buddha Heruka (Buddha he ru ka), Ratna Heruka (Ratna he ru ka), Padma Heruka (Padma he ru ka) and Karma Heruka (Karma he ru ka)35. In other Rdzogs chen texts36, the dharmakāya is associated with the clarity of unimpeded Awareness (rig pa ma ‘gags par gsal ba), the sambhogakāya with the Palace of the Skull Mansion and the nirmaṇa- kāya with the Palace of the Channels Initiating Movement. In the text all these Buddha-Bodies represent aspects of the essence of the Pristine Cognition of Awareness. Its nature, the five-coloured light and five- coloured seeds of light, pervades all channels, but resides mainly in five en- ergy-centres (‘khor lo lnga)37. These bright appearances of its nature are considered to be the self-radiation of the Peaceful and Wrathful Buddha- Bodies (zhi khro’i rang mdangs), and they are said to vary in their size from the limitless sky down to a tenth part of a single hair of a horse’s tail.

During life they remain in latency, but after death, during the visions of the Inter- mediate State of Reality Itself (chos nyid kyi bar do), there is the possibility of becoming aware of them. According to the point of view of Rdzogs chen, an adept of the Leaping Over (thod rgal) is capable of letting them manifest even during life in the form of visions projected in the clear and empty sky. The actual manifesta- tion of these visions in the sky, called “rays of light” (zer), is effected by the third aspect of Pristine Cognition of Awareness, namely compassion, by means of the Lamp of the Water that Lassos Everything at a Distance.

Since one is dealing here in the Fourth Theme with the corporeal presence of the Pristine Cognition of Awareness, its essence is likened to a Vase-Body, its nature to a butterlamp inside such a vase, and its compassion to rays of light illuminating the outer rim of the vase. But how is to be understood the statement that karma, karmic propensities, and discursive thought abide in 33 See KDYT II, p. 199. 34 See Rdo rje sems dpa snying gi me long gi rgyud chen po. TTT 56, p.147.

35 See Rgyal ba rdo rje sems dpa'i dgongs pa bstan pa thams cad kyi bu gcig pa zhes bya'i rgyud. TTT 56, p. 332. 36 See Rgyal ba rdo rje sems dpa'i dgongs pa bstan pa thams cad kyi bu gcig pa zhes bya'i rgyud . TTT 56, p. 335. 37 The energy-centre of great bliss at the crown (gtsug tor du bde chen 'khor lo), the energy- centre of perfect enjoyment at the throat (mgrin par longs spyod rdzogs pa'i 'khor lo), the energy-centre of phenomena at the heart (snying gar chos kyi 'khor lo), the energy-centre of emanation at the navel (lte bar sprul pa'i 'khor lo), and the energy-centre of maintaining bliss at the secret place (gsang gnas la bde skyong gi 'khor lo). the lungs by virtue of the power of karmic wind? To begin with, from the point of view of certain Rdzogs chen Tantras such as the Rdo rje sems dpa’ snying gi me long38, treasure texts like the ZMY39, and commentaries to be found in the TCZ, mind (sems) and its discursive thought does not abide in the lungs, but in a channel between heart and lungs.

In the following lengthy quotation one finds a description of eight aspects relating to mind40: “Fourth, there are eight specific topics of the mind, namely its base, its place, its way, its door, its essence, its potential, its activity, and its result. From among them, its base is the chest of the aggregate of form (gzugs kyi phung po). Its place is a channel (that has the size) of about a straw (sog ma) which connects the heart and the lungs and (in which) the radiation of Awareness (rig pa’i gdangs) rides on the horse of the wind (rlung gi rta). The wind is like a blind horse with legs and the radiation of Awareness resembles a cripple with eyes. Movements of conceptual thoughts will not arise, provided that these two do not mingle together. Consequently, the radiation will abide as a natural attribute (rang chas su) of Awareness itself.

Without conceptual thought about appearing objects, a distinctively clear (dangs sangs phyed pa) consciousness arises. This is the reason why one has to separate wind and Awareness by means of the pith of wind. The moving part in the arising of any conceptual thoughts on ac- count of the mingling of these two is the wind and its knowing part is the radiation of Awareness. Moreover, the Awareness inside the heart is like water itself, and its radiating potential (rtsal gdangs) having gone into the cavity of the channel (between heart and lungs) and being the mind mingled to- gether with the wind, is like a bubble. Furthermore, mind relies on the previous presence of Awareness. On the previous presence of mind, however, Awareness is not dependent.

In its essence, Awareness cannot be controlled by mind. But since (mind) is its potential, it is controlled by Awareness. When the water is not moving, there are no waves. Likewise, when Awareness is not moving, no conceptual thought of mind oc- curs. The (Rdzogs chen Tantra) Rang shar says: Mind and Awareness are exemplified by water and its bubbles. (Awareness) cannot be controlled by mind. As for its way, it moves along the life-channel (srog rtsa), because there moves the horse of mind, the life-wind (srog rlung). 38 See the Rdo rje sems dpa' snying gi me long gi rgyud, TTT 56, p. 147. 39 See ZMYT II , p. 112. 40 See TCZ II, p. 52. Its door is the mouth and the nose, because the wind is coming out there.

Its essence is the subject-object structure (gzung ‘dzin), being sam- sara itself. Its potential is the grasping of objects and the attachment to the self. Its action is bringing forth the variety of samsaric pleasure and pain. Its result is samsara and its bad migrations (ngan song) without limit.” Examples of texts localizing the mind in the lungs are the KDNYT 41, but also the ZMYT 42. However, in consideration of what has been said, it should be clear that it is not the definition of a precise site of mind that is of major im- portance here, but the assumption that mind is evolving on account of the mingling of the radiation of Awareness with wind, called in this context “karmic wind” (las rlung). It has to be noted that in Rdzogs chen one distin- guishes between the karmic wind and its counterpart, the wind of Pristine Cognition (ye shes kyi rlung).

The following quotation sheds some light on what is meant by “karmic wind”43: “But afterwards the karmic wind has arisen (which is) the grasp- ing as real (dngos ‘dzin) of the appearance of the Five Lights being the inherent potentiality (rang rtsal) of emptiness, and on account of the power of entering into grasping the inherent light of the Five Aspects of Pristine Cognitions, the Five Elementary Forces have appeared concretely: From the distillate (dangs ma) of the Five Outer Elemen- tary Forces, the Five Inner Properties (nang gi khams lnga) (of the body)44, the Six Sources of Sense Percecption (skyed mched drug)45, etc., have arisen whereby the whole of worlds and their inhabitants (snod bcud) is gradually established.” The main characteristics of the wind of Pristine Cognition, as well as its re- lationship to the karmic wind are elucidated in the following quotation46:

“In short, “wind of Pristine Cognition” is a name given to com- passion (which is) the essence of Awareness. Furthermore, on ac- count of existing as inseparable identity of essence, nature, and com- passion it is called “Pristine Cognition”. Resembling in its rudimentary movement and its rudimentary knowing (rig tsam) to the wind, it is called “wind”. 41

See KDYT II, p. 224. 42 See ZMYT I, p. 452. 43 See NYSNY, p. 8b. 44 These are apertures of the body (Space), corporeal liquids (water), metabolic heat (fire), flesh and bones (earth) and respiration (wind). 45 The Six Sources of Sense Perception (skyed mched drug) are: 1) The sense power of the eye (mig gi dbang po), 2) of the ear (rna ba'i dbang po), 3) of the nose (sna'i dbang po), 4) of the tongue (lce'i dbang po), 5) of the body (lus kyi dbang po), and 6) of the mind (yid kyi dbang po). 46 See KDYT II, p. 161. Ultimately, wind is (nothing else than) mind, the root of (the wind). After having burdened the horse of wind with rudimentary knowing which is the radiation of the Pristine Cognition, the mani- fold collection of consciousness (rnam shes kyi tshogs) has arisen. The essence of the wind of Pristine Cognition is freedom from all ex- tremes of conceptuality (spros bral) on account of its being empty.

Its nature is its appearance as Buddha-Bodies and (aspects of) Pristine Cognition on account of its being clear. Its compassion is the arising of the Pristine Cognition of omnis- cience (thams cad mkhyen pa’i ye shes) and of the Pristine Cognition of knowing all aspects (rnam pa thams cad mkhyen pa’i ye shes). Even though this (wind of Pristine Cognition) is named “wind”, it is but the inner clarity of Pristine Cognition and its outer arising as completely pure radiation which appears on the way of a yogin.” The two aspects of wind open up two different worlds of experience: The karmic wind initiates the appearances or visions of karmic propensities (bag chags kyi snang ba) as illustrated by the worlds of the Six Sentient Beings (rigs drug), and the wind of Pristine Cognition elicits the visions of Pristine Cog- nition, usually subsumed under the term “Three Buddha-Bodies”.

They are dealt with extensively in the Eighth Theme of the text. ABBREVIATIONS BMNYT Bi ma'i snying thig. In Snying thig ya bzhi. 11 vols. I / II / III / IV New Delhi: Trulku Tsewang, Jamyang and L. Tashi, 1970. BMYT I / II Bla ma yang thig. In Snying thig ya bzhi. 11 vols. New Delhi: Trulku Tsewang, Jamyang and L. Tashi, 1970. KDNYT I / II Mkha’ ‘gro snying thig. In Snying thig ya bzhi. 11 vols. New Delhi: Trulku Tsewang, Jamyang and L. Tashi, 1970. KDYT I / II / III Mkha’ ‘gro yang thig. In Snying thig ya bzhi.11 vols. New Delhi: Trulku Tsewang, Jamyang and L. Tashi, 1970. NYSNY Theg pa thams cad kyi mchog rab gsang ba bla na med pa ‘od gsal rdo rje snying po’i don rnam par bshad pa nyi ma’i snying po zhes bya ba. By Rtse le rgod tshang pa, b. 1608. In Collected Works.