List of the 227 rules of pātimokkha

Here you will the list of the 227 rules of conduct that all the bhikkhus are supposed to observe. On this page, each rule is described in a single sentence, in order to allow a short insight. By means of this latter, you will know why Buddha did establish it, in which cases it is committed, and how to get purified from it.

The 4 pārājikas

pārājika 1

"yo pana bhikkhu bikkhūnaṃ sikkhāsājīva samāpanno sikkhaṃ appaccakkhaya dubbalyaṃ anāvikatvā methunaṃ dhammaṃ paṭiseveyya, antamaso tiracchāna gatāyapi, pārājiko hoti asaṃvāso."

Not to have sexual intercourse. If a bhikkhu puts his sex in the sex, anus or mouth of a human being, man or woman – as well as in his own anus or in his own mouth –, an animal (male or female) or a dead body even if it is of the length of a sesame seed, he looses his status as a bhikkhu (for life).

Even if he does it while having his sex in plaster, in a condom, wearing the clothes of a layman, or being fully naked or not feeling any sensation (due to loss of tactile sensation on the sexual parts of the body for example), in the same way, he looses his status as a bhikkhu.

There are six cases when the pārājika 1 is not committed:

- When the bhikkhu is sleeping or in all other cases when he is not aware of the sexual intercourse when it takes place.

- When the bhikkhu is not consenting.

- When the bhikkhu has fallen into unconsciousness or is in a state of insanity.

- When the bhikkhu, being possessed by another spirit, can no longer control himself.

- When the bhikkhu is afflicted by an unbearable pain.

- When the bhikkhu has committed this action before the rules have been established.

Note: This rule is partly included within the third among the ten precepts.

pārājika 2

"yo pana bhikkhu gāmā vā araññā vā adinnaṃ theyyasiṅkhātaṃ ādiyeyya, yathārūpe adinnādāne rājāno coraṃ gahetvā haneyyuṃ vā bandheyyuṃ vā pabbajeyyuṃ vā corosi bālosi mūḷhosi thenosīti, tathārūpaṃ bhikkhu adinnaṃ ādiyamāno ayampi pārājiko hoti asaṃvāso."

Not to steal. If a bhikkhu, with an intention of theft, takes away others' possessions, has at the time and on the spot of the theft a minimum value of a quarter of the currency used during the Buddha's time (1.06 grams of gold + 1.06 grams of silver + 2.12 grams of copper, so approximately 10 euros in 2002 - 9,50), he looses his status as a bhikkhu for life.

If a bhikkhu takes possession of an object left behind by his owner or belonging to an animal, he does not commit the pārājika 2.

As soon as a bhikkhu takes an object with an intention of theft (even if he takes a single hair, even if at this particular moment he did not have the intention of taking it, or even if he afterwards abandons it), he commits the pārājika 2.

If a bhikkhu gets someone else to steal an object for him, he commits the pārājika 2.

If by common agreement, several bhikkhus decide that the one who will have the chance to steal an object will do it, and that only one bhikkhu conceals it, all bhikkhus commit pārājika 2.

The pārājika 2 is so subtle that a bhikkhu can commit it without even being aware of it.

If knowingly a bhikkhu smuggles or gets someone else to smuggle, through customs, a prohibited object (precious stones, drugs, etc.), if he lies to pay a smaller amount, travels without a valid ticket or if, out of mercy, he sets free an animal without his owner's consent, in all of these cases he commits the pārājika 2.

Several bhikkhus steal together something that they share. Each share is less than the critical sum (the quarter of the currency used in the times of Buddha, around 10 euros). However, by assembling all the shares that constitute the object of the theft, we do obtain a total value that exceeds this critical sum. All these bhikkhus have then committed the pārājika 2.

If a bhikkhu, either out of insanity, or owing to complete absentmindedness, or under the influence of an extremely painful disease, takes someone else's possession, he does not commit pārājika 2.

As soon as these five factors are present, the pārājika 3 is committed:

- The stolen object belongs to a human being.

- The bhikkhu knows that the object belongs to someone else other than himself.

- The stolen object has a minimum value of 1.06 grams of gold + 1.06 grams of silver + 2.12 grams of copper (in the concerned region).

- The bhikkhu has the intention to steal.

- The theft is done.

Note: This rule corresponds with the second of the ten precepts.

pārājika 3

"yo pana bhikkhu sañcicca manussaviggahaṃ jīvitā voropeyya,sattahārakaṃ vāssa pariyeseyya, maraṇavaṇṇaṃ vā saṃvaṇṇayya, maraṇāya vā samādapeyya, " ambo purisa kiṃ tuyhiminā dujjīvitena mataṃ te jīvitā seyyo " ti, iti cittamano cittasiṅkappo anekapariyayena maraṇavaṇṇaṃ vā saṃvaṇṇayya, maraṇāya vā samādapeyya, ayampi pārājiko hoti asaṃvāso."

Not to commit murder. If, with an intention of murder, a bhikkhu kills a human being, if he deliberately hands to a person who wants to die, a weapon likely to kill (even by believing sincerely that he is doing a favour) and this person uses it to put an end to his life, or if he expounds to a sick person the advantages of death and under this influence, the sick patient dies by not taking the medicines or food that he needed to save his life, he looses the status as a bhikkhu for life.

By ordering someone to murder someone else, by encouraging a woman to abort - and she follows this advise, by giving contraception to a pregnant woman who uses it successfully, or by requesting someone to murder an agonising person (even with the simple thought of relieving the suffering of the patient) and actually causing that person's death, in each of these cases, a bhikkhu commits pārājika 3.

By committing suicide, a bhikkhu commits pārājika 3 and thus passes away as a lay man.

If a bhikkhu asks a second bhikkhu to kill a person and the latter kills him or her, both bhikkhus commit pārājika 3. If the second bhikkhu kills a person other than the one the first bhikkhu had asked him to kill, the first bhikkhu does not commit pārājika 3. Only the second bhikkhu commits it.

The first bhikkhu asks a second bhikkhu to kill a person (or requests another person to do so). And on his behalf, this second bhikkhu hands over the work to a third bhikkhu and so on. All the bhikkhus, from the first to the last, commit pārājika 3.

With the intention to kill, a bhikkhu finds a way to kill someone (hole, trap, mine, etc.). If this has caused the death of a person, he commits pārājika 3.

As soon as these five factors are present, the pārājika 3 is committed:

- The victim is a human being.

- The bhikkhu knows that the victim is a human being.

- The bhikkhu has an intention to kill.

- The bhikkhu commits or orders a murder to be committed by someone else.

- The murder is done.

Note: This rule partly corresponds to the first of the ten precepts.

pārājika 4

"yo pana bhikkhu anabhijānaṃ uttariranussadhammaṃ attupanāyikaṃ alamariyañāṇadassanaṃ samudācareyya "itti jānāmi, itti passāmī" ti, tato aparena samayena samanuggāhīyamāno vā asamanuggāhīyamāno vā āpanno visuddhā pekkho evaṃ vadeyya "ajānamevaṃ āvuso avacaṃ jānāmi apassaṃ passāmi, tucchaṃ musā vilapi" nti aññatra adhimānā, āyapi, pārājiko hoti asaṃvāso."

Not to claim attainments of stages of pure mental concentration that have not been achieved. If with a boastful intention, a bhikkhu claims on purpose that he has eradicated the kilesās, or that he has reached some realisations (one of the four jhānas; one of the four psychic powers or one of the four stages of ariyā) although knowing that it is false; being asked or not being asked to do so, if in the field of these realisations, he asserts to know what he doesn't, if he claims to have seen something he has not, if he claims such things connected with it (for example: "I can see my previous lives"; "I can see beings dwelling in other worlds": "I definitely got rid of desire"), in each of these cases he looses his status as a bhikkhu for life.

If the person whom the bhikkhu addresses does not understand the meaning of his speech, he does not commit pārājika 4.

If a bhikkhu claims a realisation that he has really achieved, he does not commit a pārājika 4. In the same way, if a bhikkhu mentions to others a false realisation that he sincerely believes to have achieved, he does not commit pārājika 4.

As soon as these five factors are present, the pārājika is committed:

- The bhikkhu claims - in one way or another - to have achieved a realisation pertaining to the category of jhānas or the entrance into the four stages of ariyā that he has not experienced.

- The bhikkhu has the intention to boast (knowing that he has not achieved this realisation).

- The bhikkhu specifies that he is the one who achieved this realisation (if he uses an indirect way for instance: "The disciples of my teacher are the arahantas", he does not commit pārājika 4).

- The person whom the bhikkhu is addressing is a human being.

- The person whom the bhikkhu is addressing must immediately understand (if he or she does understand only a long time after, the bhikkhu does not commit pārājika 4).

The 13 saṃghādisesas

saṃghādisesa 1

"sañcetanikā sukkavissaṭṭhi aññatra supinantā saṃghādiseso."

Not to deliberately emit sperm. If a bhikkhu masturbates himself or gets someone else to masturbate him until the emission of the sperm, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

A bhikkhu must not deliberately cherish his sex with the hand, neither doing so by using an instrument, nor making it move in the air.

By doing so, if the sperm, even if it is only a tiny quantity that even a fly is able to drink, spreads from its original spot to the testicles, this bhikkhu commits the saṃghādisesa 1.

Exceptions

- While sleeping, if the sperm is released during a dream, no fault is being committed.

- While defecating, if some sperm does come out, the intention for it being absent, no fault is being committed.

- While nursing or cleaning one's sex (due to an inflammation, an injury, an insect bite, etc.) by putting medicine (cream, ointment, etc.), if some sperm is released, the desire for it being absent, no fault is being committed.

- If at time of getting into bed, wishing to ejaculate, the bhikkhu wedges his sex between his thighs or holds it strongly in his fist and whilst sleeping the sperm is released, he commits the saṃghādisesa 1.

- If the sperm is naturally released without the bhikkhu's intention to do so and that at this moment this latter does experience pleasure, he does not commit any fault.

However, if during ejaculation, he seized the opportunity to release the sperm with his hand, he commits the saṃghādisesa 1.

- If while insistently looking at the body of a woman, with a burning desire, a bhikkhu ejaculates, he does not commit a saṃghādisesa.

Note: This rule partly corresponds with the third of the ten precepts.

saṃghādisesa 2

"yo pana bhikkhu otiṇṇo vipāriṇatena cittena mātugāmena saddhiṃ kāyasaṃ saggaṃ samāpajjeyya hatthaggāhaṃ vā veṇiggāhaṃ vā aññatarassa vā aññatarassa vā aṅgassa paramasanaṃ saṃghādiseso."

Not to touch a woman. If, with the intention of a physical contact with a woman, a bhikkhu touches a woman - even a female born on that very same day - or the hair of a woman (not cut), it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

By touching a cloth or a jewel worn by a woman, a bhikkhu commits a fault but not the saṃghādisesa (provided the woman is not touched along with that part of cloth or jewel).

In the same way, by touching a woman who is a relative, his mother or sister for instance, even with a mind rid of lust, he commits a fault but not the saṃghādisesa.

By accidentally touching a woman, there is no fault. However, if a woman touches a bhikkhu, this latter must not undergo it passively, because if he takes pleasure in it, even for a short while, he immediately commits the saṃghādisesa 2.

By touching a woman with some kind of utensil, a bhikkhu commits a thullaccaya.

Note: This rule partly corresponds with the third of the ten precepts.

saṃghādisesa 3

"yo pana bhikkhu otiṇṇo vipariṇatena cittena mātugāmaṃ duṭṭhullāhi vācāhi obhāseyya yatha taṃ yuvā yuvatiṃ methunupasaṃhitāhi, saṃghādiseso."

Not to have an ill-mannered conversation with a woman.

If with a lustful state of mind, a bhikkhu utters some ill-mannered speech regarding copulation or sodomy, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

saṃghādisesa 4

"yo pana bhikkhu otiṇṇo vipariṇatena cittena mātugāmassa santike attakāmapāriyāya vaṇṇaṃ bhāseyya "etadaggaṃ bhagini pāricariyānaṃ yā rādisaṃ sīlavantaṃ kalyāṇadhammaṃ brahmacāriṃ etena dhammena paricareyyā" ti methunupasaṃhitena, saṃghādiseso."

Not to propose sexual intercourse to a woman. If with a lustful state of mind, a bhikkhu indecently proposes a woman to copulate - with him or another person - it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

A bhikkhu who tells a woman that the girls wishing to be reborn under auspicious conditions must give him their bodies, commits the saṃghādisesa 4.

saṃghādisesa 5

"yo pana bhikkhu sañcarittaṃ samāpajjeyya ittiyā vā purisamatiṃ purisassa vā ittimatiṃ jāyattane vā jārattane vā, antamaso taṅkheṇikāyapi, ]]saṃghādiseso]]."

Not to unite couples. If a bhikkhu plans encounters between men and women with the intention to unite them or if he plans encounters between prostitutes and people interested in them, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

If the following three factors are combined together, the saṃghādisesa 5 is being committed:

- Accepting to seek for information's (with an encounter between a man and a woman in mind).

- Taking these information's.

- Reporting these information's.

saṃghādisesa 6

"saññāsikāya pana bhikkhunā kuṭiṃ kārayamānena assāmikaṃ attuddesāṃ pamāṇikā kāretabbā, tatridaṃ pamāṇaṃ, dīyaso dvādasa vidattiyo sugavidattiyā, tiriyaṃ sattantarā, bhikkhū abhinetabbā vattudesanāya, tehi bhikkhūhi vattu desetabbaṃ anārambhaṃ saparikkamanaṃ, sārambhe ce bhikkhuvatthusmiṃ aparikkamane saññācikāya kuṭiṃ kāreyya, bhikkhū vā anabhineyya vatthudesanāya, pamāṇaṃ vā abhikkāmeyya, saṃghādiseso."

Not to build a housing exceeding 2.70 metres by 1.60 metres (2.95 yards by 1.74 yards), without the agreement of the saṃgha, and doing harm to living beings, or not providing enough space to turn around it.

The housing that a bhikkhu builds for himself must have a surface that will not exceed twelve measurements in length (measure by hand span; a quarter yard; nine inches) and seven in width - around 2.70 metres by 1.60 metres (2.95 yards by 1.74 yards).

Before building a housing, the bhikkhu must seek the agreement of the saṃgha by indicating the spot of the construction project.

The construction should not be done in an area where it is likely to harm insects - or other living beings.

There must be sufficient space for a cow drawn cart to move around it.

If one of these conditions is not fulfilled, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

There are places where a bhikkhu cannot build housings:

places inhabited by animals;

cultivated lands;

prison compounds;

cemetery;

a place where alcohol is being sold;

slaughterhouse area;

junctions and

crossroads.

A bhikkhu who lives in a big cave does commit no fault at all.

saṃghādisesa 7

"mahallakaṃ pana bhikkhu, vihāraṃ kārayamānena sassāmikaṃ attuddesaṃ bhikkhū abhinetabbā vatthudesanāya, tehi bhikkhūhi vatthu desetabbaṃ anārambhaṃ saparikkamanaṃ. sārambe ce bhikkhusmiṃ aparikkamane mahallamane mahallakaṃ vihāraṃ kāreyya bhikkhū vā anabhineyya vatthudesanāya, saṃghādiseso."

Not to build a monastery without the approval of the saṃgha, harming living beings or not allowing to make a whole turn around it.

If a bhikkhu whom a dāyaka requests to choose a place so as to build a house for this former, or even a monastery, doesn't respect the following points, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha:

The bhikkhu is supposed to invite other bhikkhus so as to show them the spot of the future building complex in order to get their approval.

The place of the future construction must cause absolutely no harm to living beings and must not be situated on a cultivated land.

A cart of four cows must have enough space to make a whole turn around the building.

saṃghādisesa 8

"yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhuṃ duṭṭhā doso appahīto amūlakena pārājikena dhammena anuddhaṃseyya "appeva nāma naṃ imahmā brahmacariyā sāveyya" nti, tato aparena samanuggāhīyamāno vā asamanuggāhīyamāno vā amūlakañceva taṃ adhikaraṇaṃ hoti, bhikkhu ca dosaṃ patiṭṭhāti, saṃghādiseso."

Not to groundlessly accuse a bhikkhu of having committed a pārājika.

If, with the intention to ruin the name of another bhikkhu, a bhikkhu groundlessly accuses the former of having committed a pārājika, and claims having seen or heard him doing it,

whether he launched this accusation following a question or not, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

saṃghādisesa 9

"yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhuṃ duṭṭho doso appatīto aññabhāgiyassa adhikaraṇassa kiñci desaṃ lesamattaṃ upādāya pārājikena dhammena anuddhaṃseyya "appeva nāma naṃ imahmā brahmacariyā sāveyya" nti, tato aparena samayena samanuggāhīyamāno vā asamanuggāhīyamāno vā aññabhāgiyañceva taṃ adhikaraṇaṃ hoti kocideso lesamatto upādinno, bhikkhu ca dosaṃ patiṭṭhāti, saṃghādiseso."

Not to make believe that a first bhikkhu has committed a pārājika by deliberately accusing a second one who shows similarity with the first.

If, to get others to believe that a bhikkhu has committed a pārājika, a bhikkhu deliberately accuses another person who shows a similarity with the other, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

For example, a bhikkhu sees a short, stout person stealing a box of pastries.

If this bhikkhu seizes the opportunity to get the small and fat bhikkhu who lives in his monastery and whom he does not like, accused of pārājika,

by saying that he saw a "small fat person stealing a box of sweets", he commits the saṃghādisesa 9.

We can number ten kinds of similarities:

the cast (the social rank);

the name;

the ethnical origin (the nationality);

the physical appearance;

the fault; the bowl;

the robe; the preceptor;

the instructor and

the dwelling place.

saṃghādisesa 10

"yo pana bhikkhu samaggassa saṃghassa bhedaya parakkameyya, bhedanasaṃvattanikaṃ vā adhiraṇaṃ samādāya paggahya tiṭṭheyya, so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi evamassa vacanīyo "māyasmā samaggassa bhedāya parakkami, bhedanasaṃvattanikaṃ vā adhikaraṇaṃ samādāya paggahya aṭṭhāsi, sametāyasmā saṃghena, samaggohi saṃgho sammodamāno avivadamāno ekuddeso phāsu viharatī" ti, evañca so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi vuccamāno tatheva paggahṇeyya, so bhikkhu bhikkhūgi yāvatatiyaṃ samanubhāsitabbo tassa paṭinissaggāya, yāvatatiyañce samanubhāsiyamāno taṃ paṭinissajjeyya, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, no ce paṭinissajjeyya, saṃghādiseso."

Not to create a division within the saṃgha.

If a bhikkhu attempts to destroy the equilibrium or the harmony that prevails between the members of the saṃgha, these latter must tell him:

"Do not destroy the harmony that prevails within the saṃgha.

Do not do anything that is likely to divide the saṃgha. Leave the saṃgha and the moral principles intact.

If the saṃgha remains united, there could be only heartfelt joy and absence of mutual discord within it.

By expounding the pātimokkha all together, bhikkhus will remain tranquil, free of troubles". If, after having been stated these principles of virtuous conduct by means of a specific formula, the bhikkhu does not reject his view point, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

Among the bhikkhus who attempt to create a division within the saṃgha, those who reject their incorrect opinions, who are insane, who are unconscious or who are afflicted by intense physical pain, do not commit the saṃghādisesa 10.

Here are the eighteen ways to attempt to create a division within the saṃgha:

Asserting that...

1) that which is not the dhamma is the dhamma); 2) that which is the dhamma is not the dhamma);

3) that which is not vinaya is the vinaya;

4) that which is vinaya is not the vinaya;

5) that which Buddha has not taught has been taught;

6) that which Buddha has taught has not been taught;

7) that which Buddha has not repeated has been repeated;

8) that which Buddha has repeated has not been repeated;

9) that which Buddha has not established has been established;

10) that which Buddha has established has not been established;

11) a fault that wasn't committed has been committed;

13) a fault that was committed has not been committed;

13) a minor fault when it is about a serious fault;

14) a serious fault when it is about a minor fault; 1

5) an exception of a fault is not one;

16) that which is not an exception of a fault is one;

17) a fault is committed owing to a vulgar attitude (impolite) when it is not so;

18) a fault is not committed owing to a vulgar attitude when it is so.

saṃghādisesa 11

"tassova khopana bhikkhussa bhikkhū honti anuvattakā vaggavādakā eko vā dve vā tayovā, te evaṃ vadeyyuṃ "māyasmanto etaṃ bhikkhu kiñci avacuttha, dhammavādī ceso bhikkhu, vinayavādi ceso bhikkhu, ahmākañce so bhikkhu chandañca ruciñce ādāya voharati, jānāti, no bhāsati, ahmāka' mpetaṃ khamatī" ti', te bhikkhū bhikkhuhi evassu vacanīyā "māyasmanto evaṃ avacuttha, na ce' so bhikkhu dhammavādī, na ce' so bhikkhu vinayavādī, māyasmantānampi saṃghabhedo ruccittha, sametāyasmantānaṃ saṃghena, samaggohi saṃgho sammodamāno avivadamāno ekuddeso phāyu viharatī" ti, evañca te bhikkhū bhikkhūhi vuccamānā tatheva paggahṇeyyuṃ, te bhikkhū bhikkhūhi yāvatatiyaṃ samanubhāsitabbā tassa paṭinissaggāya, yāvatatiyañce samanubhāsiyamānā taṃ paṭinissajjeyyuṃ, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, no ce paṭinissajjeyyuṃ, saṃghādiseso."

Not to encourage a bhikkhu who works to divide the saṃgha.

If one (or several) bhikkhus support another bhikkhu who works to divide the saṃgha, the bhikkhu(s) who notice or hear him doing so, must tell him: "Do not follow this bhikkhu."

If he does not obey this interdiction, the witnessing bhikkhus must then reiterate this prohibition by giving him a lesson using a specific formula.

If the prohibition (to side with the bhikkhu provoking a division in the saṃgha) is posed a second and then a third time, by means of the same formula, but the bhikkhu still doesn't reject his opinion, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

saṃghādisesa 12

"bhikkhu paneva dubbacajātiko yoti uddesapariyāpannesu sikkhāpadesu bhikkhūhi sahadhammikaṃ vuccamāno attānaṃ avacanīyaṃ karoti "māmaṃ āyasmanto kiñci avacuttha kalyāṇaṃ vā pāpakaṃ vā, ahampāyasmante na kiñci vakkhāmi kalyāṇaṃ vā pāpakaṃ vā, viramathāyasmanto mama vacanāyā" ti, so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi evamassa vacanīyo "māyasmā attānaṃ avacanīyaṃ akāsi, vacanīyamevā - yasmā attanaṃ karotu, āyasmāpi bhikkhū vadatu sahadhammena, bhikkhūpi āyasmantaṃ vakkhanti sahadhammena, evaṃ saṃvaddhā hi tassa bhagavato parisā yadidaṃ aññamañña vacanena aññamaññavuṭṭhāpanenā" ti evañcaso bhikkhu bhikkhūhi vuccamāno tatheva paggahṇeyya, so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi yāvatatiyaṃ samanubhasitabbo tassa paṭinissaggāya, yāvatatiyañce samanubhāsiyamāno taṃ paṭinissajjeyya, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, no ce paṭinissajjeyya, saṃghādiseso."

Not to reject admonishments made on his behaviour.

If a bhikkhu does not respect the rules of the vinaya, if he does something which is in discord with the vinaya,

those among the bhikkhus living with him who see or hear him doing so, are obliged to make him notice his behaviours or actions,

which are not proper and that he must abstain from them.

If he responds by refusing to obey, the other bhikkhus must teach him a moral lesson by means of a specific formula.

If after having admonished him in the same way for a second and then a third time, he refuses to give up his opinion, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

The bhikkhu must not refuse to listen to remarks made on his behaviour, even if he is the most respected one in the monastery and even if the remarks are made by a bhikkhu of less seniority, because if they are legitimate and he objects to them,

he is likely to undergo the procedure entailing the saṃghādisesa 12.

saṃghādisesa 13

"bhikkhu panena aññataraṃ gāmaṃ vā nigamaṃ vā upanissāya viharati kuladūsako pāpasamācāro, tassa kho pāpakā samācārā dissanti ceva suyyantica, kuvāni ca tena duṭṭhāni dissanti ceva suyyanti ca. so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi evamassa vacanīyo "āyasmā kho kuladūsako pāpasamācāro, āyasmato kho pāpakā samācārā dissanti ceva suyyanti ca, kulāni āyasmatā duṭṭhāni dissanti ceva suyyanti ca, pakkamatāyasmā imahmā āvāsā, alaṃ te idha vāsenā" ti, evañca so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi vuccamāno te bhikkhū evaṃ vadeyya "chandagāmino ca bhikkhū, dosagāmino ca bhikkhū, mohagāmino ca bhikkhū, bhayagāmino bhikkhū, tādisikāya āpattiyā ekaccaṃ pabbājenti ekaccaṃ na pabbājenti" ti. so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi evamassa vacanīyo "māyasmā evaṃ avaca, na ca bhikkhū chandagāmino, na ca bhikkhū dosagāmino na ca bhikkhū, mohagāmino na ca bhikkhū, bhayagāmno, āyasmā kho kuadūsako pāpasamācāro, āyasmato kho pāpakā samācārā dissanti ceva suyyanti ca, kulāni cāyasmatā duṭṭhāni dissanti ceva suyyanti ca, pakkamatāyasmā imahmā āvāsā, alaṃ te idha vāsenā" ti, evañca so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi vuccamāno tatheva paggahṇeyya, so bhikkhu bhikkhūhi yāvatatiyaṃ samanubhāsitabbo tassa paṭinissaggāya, yāvatatiyañce samanubhāsiyamāno taṃ paṭinissajjeyya, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, no ce paṭinissajjeyya, saṃghādiseso."

Not to spoil the confidence and the consideration that the people have for the dhamma.

By seeing or by hearing a bhikkhu committing actions or indulging in behaviours that corrupt others' faith in dhamma, other bhikkhus are supposed to tell him:

"Your behaviour is spoiling the confidence and the consideration that the people have for the dhamma.

Your conduct is mediocre. We saw and heard the way you behave. You must leave from here. Do not stay in this monastery."

Being expelled, if he refuses to leave and counteracts, the bhikkhus who see or hear him reacting this way, should expel him by teaching him a moral lesson a second time.

If by the third time, he again refuses to obey, he should be brought before the saṃgha and be again pronounced thrice consecutively the discourse of expulsion.

After this, if he still decides not to reject his opinion, it is proper to teach him a moral lesson by means of a specific formula.

If after the second, then the third moral discourse pronounced by means of this formula, he doesn't step down from his stance, from this moment onward, it entails a meeting of the saṃgha.

Corruption

The bhikkhus who offer presents to the dāyakas spoil the faith and the confidence that these people have in the dhamma.

Buddha does not accept this kind of gift.

He only pleads in favour of gifts that the dāyakas give to the bhikkhus as the former do believe in the benefits derived from their sīla, their wisdom.

In the same way, he stands firmly opposed to exchanges and donations done between the laity and the bhikkhus, which are motivated by links established between recipients and duty bound persons.

The fact that the bhikkhus offer things to dāyakas is highly likely to deteriorate the respectful consideration that the latter have for the saṃgha, and thus their faith in the dhamma.

The people who come close to the bhikkhus and who give offerings to them will no longer see any benefit in doing so and will not do so to the ones who cultivate a good sīla and who are realised. However, a bhikkhu can give some fruits that he possesses to his family members.

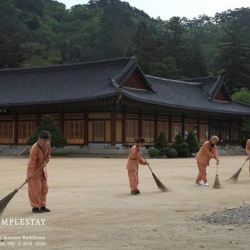

Some bhikkhus can give food or some remaining hygienic products to the laity who perform sweeping, dish washing or gardening work, etc. In this case, there is no corruption of the faith, therefore no fault is being committed.

To make sure that the bhikkhus do not commit faults, it is better that the laity carry out their duties first and then receive some food or something to drink.

After having taken their meal, in order not to waste food, the bhikkhus should give their remaining food to the laity.

The bhikkhu who has performed an act of corruption should be expelled from the village or from the area where he lives.

If he gives belongings or medical treatments all over the town, he must be expelled from this town.

If he starts to criticise the saṃgha without leaving the area, he must be taken to the sīmā where the saṃgha will have to pronounce the appropriate formulas.

After this, if he refuses to obey, the saṃgha must reprimand him.

By the end of the third announcement of this formula, if this bhikkhu has still not decided to leave his area, he commits the saṃghādisesa 13.

The 2 aniyatas

aniyatā 1

"yo pana bhikkhu mātugāmena saddhiṃ eko ekāya raho paṭicchanne āsane alaṃkammaniye nisajjaṃ kappeyya, tamenaṃ saddheyyavacasā upāsikā disvā tiṇṇaṃ dhammānaṃ aññatarena vadeyya pārājikena vā saṃghādisesena vā pācittiyena vā nisajjaṃ bhikkhu paṭijāmāno tiṇṇa dhammānaṃ aññtarena kāretabbo pārājikena vā saṃghādisesena vā pācittiyena vā, yena vā sā saddheyyavacasā upāsikā vadeyya, tena so bhikkhu kāretabbo, ayaṃ dhāmmo aniyato."

Not to be found alone with a woman in a remote place that can arise suspicions about a sexual intercourse. A bhikkhu is found alone with a woman in a place remote from others' sight, where a sexual intercourse is possible (in a place hidden behind a wall, curtains, etc.). They are seated together, being not in the presence of another woman or man who is able to understand. If a trustworthy person, seeing this bhikkhu, brings an accusation before the saṃgha, whether it concerns a pārājika, a saṃghādisesa or else a pācittiya, the accused bhikkhu finds himself in the case of indefinite fault and he is duty bound to admit the fault that he has committed.

By being isolated with a girl born on the same day, a bhikkhu is not spared from committing this fault.

aniyatā 2

"naheva kho pana paṭicchannaṃ āsanaṃ hoti, nālaṃkammaniyaṃ, alañca kho hoti mātugāmaṃ duṭṭhullāhi vācāhi obhāsituṃ, yo pana bhikkhu tathārūpe āsane mātugāmena saddhiṃ eko ekāya raho raho nisajjaṃ kappeyya, tamenaṃ saddheyyavacasā upāsikā disvā dvinnaṃ dhammānaṃ aññatarena vadeyya saṃghādisesena vā pācittiyena vā, nisajjaṃ bhikkhu paṭijānamāno dvinnaṃ dhammānaṃ aññtarena kāretabbo saṃghādisesena vā pācittiyena vā, yena vā sā saddheyyavacasā upāsikā vadeyya, tena so bhikkhu kāretabbo, ayaṃpi dhammo aniyato."

Not to be found alone with a woman in an isolated place that can arise suspicions about conversations on lustful subjects. A bhikkhu is found alone with a woman in an open place within the reach of others' sight, but from where one cannot hear what is being said, and about which one can imagine that the conversation bears a lustful character. They are seated together, without the presence of another woman or man able to understand. If a trustworthy person, seeing this bhikkhu and being in the position to suspect a saṃghādisesa or a pācittiya, brings an accusation before the saṃgha, the accused bhikkhu finds himself in the case of an indefinite fault and he is duty bound to admit the fault that he has committed.

The fact that it is not possible to hear the words said in a place non remote from sights may be due to the surrounding noise, the presence of a transparent wall (glass), or else to a remote distance (starting from twelve cubits, approximately 6 meters).

The 30 nissaggiyas

1st part, cīvara

nissaggiya 1

"niṭṭhitacīvarasmiṃ bhikkhunā ubbhatasmiṃ kathine dasāhaparamaṃ atinekacīvaraṃ dhāretabbaṃ, taṃ atikkāmayato nissaggiaṃ pacittiaṃ."

Not to keep an extra robe more than ten days at a time. If a bhikkhu keeps his non-determined robe more than ten days, it entails a pācittiya and irremediably calls for the forfeiture of this robe. This robe must be momentarily handed over to another bhikkhu by means of an authoritative formula, and then the latter returns the robe. Then, the bhikkhu who has committed the nissaggiya must perform the desanā.

This only concerns the robes being worn, as old robes can be used as a curtain, a carpet, etc. Then a bhikkhu cannot determine a new robe as long as the determination of the old robe has not been overruled.

There are four exceptions according to which a bhikkhu can keep a non-determined robe more than ten days at a time:

- When the tailoring of the robe has not been completed.

- When the bhikkhu comes across inauspicious conditions in the monastery in which he spends the vassa.

- During the month of kathina (from the first day following the full moon bringing the vassa to an end, until the following full moon).

- During the five months following the vassa, if benefits are derived out of the kathina.

This rule only concerns the robes being worn, because a bhikkhu could definitely own others that he uses as carpets, curtains, etc. The way to give up a robe nissaggiya 1

The bhikkhu who committed the fault of having kept an extra robe more than ten days at a time, must give up this robe nissaggiya before doing the desanā. The formula of this forfeiture can be uttered in pāḷi or in another language.

"idaṃ me bhante cīvaraṃ dasāhātikkantaṃ nissaggiyaṃ, imāhaṃ āyasmato nissajjāmi".

"Venerable, I must give up this robe that I have kept more than ten days. This robe, I leave it to you."

After having relinquished the robe, it is necessary to purge the pācittiya caused by the nissaggiya by means of desanā. Afterwards, the bhikkhu who receives the robe nissaggiya returns it to the bhikkhu who has committed the nissaggiya while uttering in pāḷi, or another language:

"imaṃ cīvaraṃ āyasmato dammi."

" This robe Venerable, I return it to you."

nissaggiya 2

"niṭṭhitacīvarasmiṃ bhikkhunā ubbhatasmiṃ kathine ekarattaṃpi ce bhikkhu ticīvarena vippavaseyya, aññatra bhikkhusammutiyā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to spend the night far from one of his three robes. Once a bhikkhu has managed to finish the tailoring of his robe, if he does no longer and doesn't come

across any inauspicious conditions at vassa's time, and he is not sick, spending the night without one of the three determined robes, it entails a pācittiya and irremediably calls for the forfeiture of this robe. The way to give up a robe nissaggiya 2

The formula of this abandonment can be recited in pāḷi or in another language.

"idaṃ me bhante cīvaraṃ rattivippavutthaṃ aññatra bhikkhusammutiyā nissaggiyaṃ, māhaṃ āyasmato nissajjāmi."

"Venerable, I must give up this robe that I left far behind me overnight. This robe, I leave it to you."

If the bhikkhu thinks that he will spend dawn far from one of his three robes, he can recite the formula meant for eliminating the determination of this robe and so, be free from nissaggiya...

If it concerns the double robe:

"etaṃ saṃghāṭiṃ paccuddharāmi."

I abolish the determination of this second robe."

If concerns the upper robe:

"etaṃ uttatāsaṅgaṃ paccuddharāmi."

"I abolish the determination of the upper robe."

If it concerns the lower robe:

"etaṃ antaravāsakaṃ paccuddharāmi."

"I abolish the determination of this lower robe."

A bhikkhu who spends a night until dawn without one of his three robes can re-determine it

the day after. In this case, he does not commit the nissaggiya 2.

nissaggiya 3

"niṭṭhitacīvarasmiṃ bhikkhunā ubbhatasmiṃ kathine bhikkhuno paneva akālacīvaraṃ uppajjeyya, ākaṅkhamānena bhikkhunā paṭiggahetabbaṃ, paṭiggahetvā khippameva kāretabbaṃ, no ca' ssa pāripūri, māsaparamaṃ tena bhikkhunā taṃ cīvaraṃ nikkhipitabbaṃ ūnassa pārikapūriyā satiyā paccāsāya. tato ce uttari nikkhipeyya satiyāpi paccāsāya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to keep the clothing material meant for the tailoring of a robe more than one month at a time. If a bhikkhu succeeded in completing the tailoring of a new robe, if he does no longer or doesn't come across any inauspicious conditions during a vassa and if he is not sick, when some clothing materials are set apart and meant for a new robe, it must be sewed in the forthcoming ten days, (in accordance with the nissaggiya 1). If there is not enough clothing material and the bhikkhu is still expecting to receive some to finish this robe, the material can be kept for a month – a lunar month. If this period is exceeded, it entails a pācittiya and irremediably calls for the abandon of the unfinished robe. To purge this fault, it is advisable to give up the robe in the presence of another bhikkhu by means of the following formula in pāḷi or in another language:

"imaṃ me bhante akālacīvaraṃ māsātikkantaṃ nissaggiyaṃ, imāhaṃ āyasmato nissajjāmi."

"I must give up this robe "exceeding the allotted period" that I have kept more than a month. This robe Venerable, I leave it to you."

After having given up this robe, it is necessary to do the desanā to purify the pācittiya that is inherent to this fault.

Note: In today's world, given that the robes are already sewed (ready-made), the nissaggiya 3 has virtually no longer any chance to be committed.

nissaggiya 4

"yo pana bhikkhu aññātikāya bhikkhuniyā purāṇacīvaraṃ dhovāpeyya vā rajāpeyya vā ākoṭāpeyyavā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to have a robe washed or dyed by a bhikkhunī who is not a relative. If a bhikkhu gets his "old" robe washed, dyed or dried through hitting by a bhikkhunī, who is not an offspring of his family up to the seventh generation, he commits a fault irremediably calling for the abandonment of his robe and entailing a pācittiya.

As soon as the robe has been worn or used as a pillow, it is considered as "old". The seven generations of the family

The seven generations of the family corresponds with his own generation, to the three who are backward and to the three subsequent ones after himself. Worth to come to know:

- great-grand-parents,

- grand-parents,

- brothers and sisters,

- children,

- grand-children,

- great grand-children.

nissaggiya 5

"yo pana bhikkhu aññātikāya bhikkhunīyā hatthato cīvaraṃ paṭiggahṇeyya aññatra pārivattakā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept a robe from a bhikkhunī who is not a relative. If, this not being an exchange, a bhikkhu accepts a robe from the hands of a bhikkhunī who is not a relative of his, it irremediably calls for the abandon of the robe and entails a pācittiya.

A piece of clothing material is considered as a "robe" as soon as it has a width of a quarter of a yard - about 20 centimetres / 9 inches - and an cubit's length - about 50 centimetres / 19 inches. If a bhikkhu receives from a bhikkhunī a clothing material measuring at least these dimensions, under the agreement of an exchange even only with a myrobolan (symbolic, because it is only a valueless small fruit), no fault is being committed by accepting it.

nissaggiya 6

"yo pana bhikkhu aññātakaṃ gahapatiṃ vā gahapatāniṃ vā cīvaraṃ viññāpeyya aññtra samayā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ. tatthāyaṃ samayo, acchinnacīnaro vā hoti bhikkhu naṭṭhacīvaro vā, ayaṃ tattha samayo."

Not to ask someone who is not a relative for a robe. If a bhikkhu asks for a robe from a dāyaka who is not a relative of his and he gets one, this irremediably calls for the abandonment of this robe and entails a pācittiya. However, in case the robe is stolen or destroyed, it is permissible to ask for one from anybody. Also, when a dāyaka has invited a bhikkhu to ask from him, the latter can freely inform him of the need for the robe.

Here is the formula which is appropriate to say - in pāḷi or in another language - in front of one or several bhikkhus, in order to proceed to the abandonment of the robe nissaggiya:

"idaṃ me bhante cīvaraṃ aññātakaṃ gahapatikaṃ aññatra samayā viññāpitaṃ nissaggiyaṃ, imāhaṃ saṃghassa imāhaṃ āyasmantānaṃ (āyasmato) nissajjāmi."

"Venerable(s), I must give up this robe that I asked from a dāyaka who is not a relative of mine. This robe, I leave it to the saṃgha, venerable(s)."

After having given up the robe, the fault must be purged by means of desanā.

By forcing a dāyaka, who invited him to ask for what he requires, to offer a robe or a material that he does not want to give, a bhikkhu commits the nissaggiya 6. In this case, depending on the value of the material and the way the offering has been forced, the pārājika 2 may be committed.

nissaggiya 7

"tañce aññātako gahapati vā gahapatānī vā bahūhi cīvarehi abhihaṭṭhu pavāreyya, santaruttaraharamaṃ tena bhikkhunā tato cīvaraṃ sāditabbaṃ, tato ce uttari sādiyeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to ask for more than one upper robe and one lower robe in case of loss of the three robes. If a bhikkhu whose robes were stolen or destroyed asks from a dāyaka who is not a relative of his, for one or several robes in addition to one for the upper part and one for the lower part of the body, or of dimensions exceeding these two robes, it irremediably calls for the abandonment of the robe or robes received in addition to those that he was authorised to ask for, and it entails a pācittiya.

If a bhikkhu is deprived of his robes, whether they have been hidden, destroyed by fire, taken away by waters, bitten by rats, etc., he can ask for others from the dāyaka (even among those who have not set such a proposal) who are not relatives of his. However, it is advisable to be offered two robes at the most: an upper and a lower robe. The bhikkhu who accepts a larger number of them commits the nissaggiya 7.

The bhikkhus who had their robes stolen, or else destroyed in one way or another, can ask for robes from a dāyaka who is not a relative of his without exceeding the maximum permitted:

- If one robe has been lost, the bhikkhu cannot ask for a robe.

- If two robes have been lost, only one robe can be asked for.

- If three robes have been lost, at the most two robes can be asked for.

However, a bhikkhu who looses the only two robes that he possesses, can ask for two. It is also advisable to ask for more than two robes from a dāyaka who has previously expressed the request to ask him in case it was needed (robes or objects pertaining to the four requisites), and also from his relatives up to the seventh generation (please refer to the list in nissaggiya 4).

nissaggiya 8

"bhikkhuṃ paneva uddissa aññātakassa gahapatissa vā gahapatāniyā vā cīvaracetāpannaṃ upakkhaṭaṃ hoti "iminā cīvaracetāpannena vīvaraṃ cetāpetvā itthannāmaṃ bhikkhuṃ cīvarena acchādessāmī" ti, tatra ceso bhikkhu pubbe appavārito upasaṅkamitvā cīvare vikappaṃ āpajjeyya "sādhu vata maṃ āyasmā iminā cīvaracetāpannena evarūpaṃ vā evarūpaṃ vā cīvaraṃ cetāpetvā acchādehī" ti kalyāṇakamyataṃ upādāya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ"

Not to ask for a good quality robe from a dāyaka who is saving money to offer one. If a bhikkhu asks for a robe of good quality from a dāyaka - who is not a relative of his, the latter having not expressed, to the former, the request to be asked for it, - who saves money to offer him one and this good quality robe costs more than the one supposed to be offered at first, that he asks him to exchange the robe that is meant to be offered or else to buy another, that he specifies the width or the length, that he asks for one that has a softer touch or else he specifies other features and if he gets the robe according to his wishes, it irremediably calls for the abandonment of this robe and entails a pācittiya.

If the value of the robe being purchased according to the specific request of the bhikkhu doesn't exceed the value of the one meant at first, the nissaggiya 8 is not being committed.

nissaggiya 9

"bhikkhuṃ paneva uddissa ubhinnaṃ aññātakānaṃ gahapatīnaṃ vā gahapatānīnaṃ vā paccekacīvaracetāpannāni upakkhaṭāni honti "imehi mayaṃ paccekacīvaracetāpannehi paccekacīvarāni cetāpetvā itthannāmaṃ bhikkhuṃ cīvarehi acchādessāmā" ti, tatra ceso bhikkhu pubbe appavārito upasaṅkamitvā cīvare vikappaṃ āpajjeyya "sādhu vata maṃ āyasmanto imehi paccekacīvaracetāpannehi evarūpaṃ vā evarūpaṃ vā vīvaraṃ cetāpetvā acchādetha ubhāva santā ekenā" ti kalyāṇakamyataṃ upādāya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to ask for a good quality robe from two dāyakas who are saving money to offer one each. If a bhikkhu proceeds to the house of one of the two dāyakas - none of them being relatives of his - the latter both willing to offer a robe, and this former having not been requested to do so asks them to get together to offer him a robe worth more that one of the two robes that these dāyakas had thought to offer at first, by imposing specifications as to the robe's width or length, if he gets offered this robe the way he asked for, he is obliged to relinquish it and in entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 10

"bhikkhuṃ paneva uddissa rājā vā rājabhoggo vā brāhmaṇo vā gahapatiko vā dūtena cīvaracetāpannaṃ pahiṇeyya "iminā cīvaracetāpannena cīvaraṃ cetāpetvā itthannāmaṃ bhikkhuṃ cīvarena acchādehī" ti. so ce dūto taṃ bhikkhuṃ upasaṅkamitvā evaṃ vadeyya "idaṃ kho bhante āyasmantaṃ uddissa cīvaracetāpannaṃ ābhataṃ, paṭiggahṇātu āyasmā cīvaracetāpannaṃ" nti. tena bhikkhunā so dūto evamassa vacanīyo "na kho mayaṃ āvuso cīvaracetāpannaṃ paṭiggahṇāma, cīvarañca kho mayaṃ paṭiggahṇāma kālena kappiya" nti. so ce dūto taṃ bhikkhuṃ evaṃ vadeyya "atthi panāyasmato koci veyyāvaccakaro" ti. cīvaratthikena bhikkhunā veyyāvaccakaro niddisitabbo ārāmiko vā upāsako vā "eso kho āvuso bhikkhūnaṃ veyyavaccakaro" ti. so ce dūto taṃ veyyavaccakaraṃ saññāpetvā taṃ bhikkhuṃ upasaṇkamitvā evaṃ vadeyya "yaṃ kho bhante āyasmā veyyāvaccakaraṃ niddisi, saññatto so mayā, upasaṅkamatuāyasmā kālena, cīvarena taṃ acchādessatī. cīvaratthikena bhikkhave bhikkhunā veyyāvaccakaro upasakaṅkamitvā dvattikkhattuṃ codetabbo sāretabbo" attho me āvuso cīvarenā" ti, dvattikkhattuṃ codayamāno sārayamāno taṃ cīvaraṃ abhinipphādeyya, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, no ce abhinipphādeyya, catukkhattuṃ pañcakkhattuṃ chakkhattuparamaṃ tuhṇībhūtena uddissa ṭhātabbaṃ, catukkhattuṃ pañcakkhattuṃ chakkhattuparamaṃ tuhṇībūto uddissa tiṭṭhamāno taṃ cīvaraṃ abhinipphādeyya, iccetaṃ kusalaṃ, tato ce uttari vāyāmamāno taṃ cīvaraṃ abhinipphādeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ. no ce abhinipphādeyya, yatassa cīvaracetāpannaṃ ātataṃ, tattha sāmaṃ vā gantabbaṃ, dūto vā pāhetabbo "yaṃ kho tuhme āyasmanto bhikkhuṃ uddissa cīvaracetāpannaṃ pahiṇittha, na taṃ tassa bhikkhuno kiñci atthaṃ anubhoti, yuñjantāyasmanto sakaṃ, mā vo sakaṃ vinassā" ti, ayaṃ sattha sāmīci."

Not to appoint a kappiya on his own, nor to be too pushy with a kappiya who is supposed to provide something. If a person willing to offer a robe to a bhikkhu, sends an emissary to hand over money to the said bhikkhu, and his emissary asks him to accept it explaining that it is meant for a robe, this bhikkhu must reply to him: "I do not accept money. I can only accept a robe."

This emissary can then say to the bhikkhu: "Venerable, I will refer the matter to a kappiya." This bhikkhu can appoint a kappiya to this emissary only if he is requested to do so or if he already has one.

The emissary proceeds to the kappiya and hands him over money saying: "Friend, this sum that I am giving you is meant to buy a robe for this particular bhikkhu", naming the bhikkhu referred to.

Once this emissary has been understood by the kappiya, he proceeds back to the bhikkhu by informing him: "Venerable, I made the said kappiya understand clearly what is meant; at the required time, you could go to him so as to get a robe."

By approaching a kappiya, this bhikkhu could tell him at the most: "I need a robe." He can repeatedly ask him so twice or thrice. After these reminders, if the robe is still not obtained, he could show up before this kappiya up to six times by remaining standing and silent. If at the end of the three oral utterances and having stood silent six times, the robe is not still not obtained, if this bhikkhu says or does anything else to get this robe and he finally gets it, it irremediably calls for the abandonment of the robe and entails a pācittiya.

If the bhikkhu has not succeeded in getting a robe - after three oral utterances have been made and having stood in silence six times -, it is advisable that he himself goes to the person wishing to offer the robe or sends an emissary to carry his message: "dāyaka, the money meant for this robe has been entrusted. Such-and-such bhikkhu didn't receive anything. dāyaka, please get your money back to make sure that you have not lost it."

The vinaya applies this rule in the same way regarding offerings of other kinds such as exercise books, food, medicine, lodging, etc.

2nd part, kosiya

nissaggiya 11

"yo pana bhikkhu kosiyamissakaṃ santhataṃ kārāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept carpets containing silk. If a bhikkhu is being offered a floor carpet made out of silk, he must relinquish it and it entails a pācittiya. Even if such a carpet does not contain one thread of silk, the nissaggiya 11 is being committed. However, by using silken material such as an anti-dust cloth, a curtain, a floor cover or a pillow, no fault is being committed.

Note: These types of carpets are hardly used nowadays. Not to be mistaken with the piece of square material used to cover floors (nissīdana).

nissaggiya 12

"yo pana bhikkhu suddhakāḷakānaṃ eḷakalomānaṃ santhataṃ kārāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept the floor carpets only made of black sheep wool. If a bhikkhu sews or causes someone else to offer him a floor carpet only made of black sheep wool – which is devoid of any other colours –, he cannot use it and must forsake it, and it entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 13

"navaṃ pana bhikkhunā santhataṃ kārayamānena dvebhāgā suddhakāḷakānaṃ eḷakalomānaṃ ādātabbā tatiyaṃ odātānaṃ catutthaṃ gocariyānaṃ. anādā ce bhikkhu dve bhāge suddhakāḷakānaṃ eḷakakomānaṃ tatiyaṃ odātānaṃ catutthaṃ gocariyānaṃ navaṃ santhataṃ kārāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept a floor carpet that is, for more than half of it, made with black sheep wool and a quarter in white wool. A bhikkhu who makes or causes someone else to offer him a floor carpet can utilise plain black sheep wool. However, he can do it for half of the carpet at the most. He must incorporate white sheep wool for at least a quarter of the carpet as well as a wool or another colour, according to his wishes, for at least a quarter of the carpet.

If a bhikkhu purchases a floor carpet and does not respect its proportions, he commits a fault irremediably calling for the definitive abandonment of this carpet and entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 14

"navaṃ pana bhikkhunā santhataṃ kārāpetvā chabbassāni dhāretabbaṃ, orena ce channaṃ vassānaṃ taṃ santhataṃ vissajjetvā vā avissajjetvā vā aññaṃ navaṃ santhataṃ kārāpeyya aññatra bhikkhusammutiyā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to get another floor carpet as long as the former is not six years old yet. A bhikkhu who makes or causes someone else to make him a new floor carpet must keep it for six years before getting a new one. If during these six years he gets another, this new carpet must be given up, he cannot get it back and the bhikkhu commits a pācittiya.

To a bhikkhu undergoing stages of bad health, who cannot take his floor carpet along with him when he is travelling, it is allowed to get a new one from the saṃgha during the six years period. Although it is forbidden to make or to ask for a floor carpet during this six years period, it is allowed to make one for another bhikkhu. It is also allowed to accept one during this period if someone spontaneously offers one or if the old one is lost or no longer in a good shape.

nissaggiya 15

"nisīdanasanthataṃ pana bhikkhunā kārayamānena purāṇasantha tassa sāmanthā sugatavidatthi ādātabbā dubbaṇṇakaraṇāya, anādā ce bhikkhu purāṇasantha tassa sāmantā sugatanidatthiṃ navaṃ nisīdanasanthataṃ kārāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to make a new carpet without adding a part of the old one. If a bhikkhu makes a new floor carpet without incorporating into it a portion of the margin of the old one (it should at least measure the minimum dimension of Buddha's measurement, approximately 60 centimetres / 16.5 inches), he must give up this carpet, which in no wise can be utilised and commits a pācittiya.

Concerning the portion that one should take from the old floor carpet so as to incorporate it into the new one, if the remaining piece worthy of use measures less than a quarter yard – 9 inches – 22 centimetres, most of it must be got back. If there is nothing to be reutilised from the old floor carpet, the bhikkhu can then make a new floor carpet without adding any piece from the old one.

If the old floor carpet is still in a good shape, it is also possible (rather than making entirely another carpet) to add wool so as to complete it.

nissaggiya 16

"bhikkhuno paneva addhānamaggapaṭi pannassa eḷakalomāni uppajjeyyuṃ, ākaṅkhamānena bhikkhunā paṭiggahetabbāni. paṭiggahetvā tiyojanaparamaṃ sahatthā haritabbāni asante hārake. tato ce uttari tareyya asantepi hārake, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to carry wool along with oneself for more than three walking days. If a bhikkhu who needs sheep wool has no one to carry it for him on a distance exceeding the one corresponding to three walking days, this wool must be abandoned and it entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 17

"yo pana bhikkhu aññātikāya bhikkhunīyā eḷakalomāni dhovāpeyya vā rajāpeyya vā vijaṭāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to make someone else wash, dye or card the wool for a bhikkhunī. If a bhikkhu causes wool to be washed, dyed or carded by a bhikkhunī who is not a relative of his, he must abandon this wool and it entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 18

"yo pana bhikkhu jātarūparajataṃ uggahṇeyya vā uggahṇāpeyya vā upanikkhittaṃ vā sādiyeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept money. If a bhikkhu accepts or receives in one way or another, gold or money, it must immediately be relinquished and it entails a pācittiya.

What ought to be considered as gold or money are: all precious metals, coins, bank notes, checks, credit cards, restaurant tickets or any other type of monetary means (all that which enables to buy something). However, telephone cards, stamps and transportation tickets do not belong to this category as these things do not enable one to do shopping.

To proceed in the forfeiture of gold or money, all the bhikkhus of the vihāra meet in the sīmā and appoint a bhikkhu - renowned for his honesty - who will go and throw this gold or money outside of the monastery without bothering to take note of the spot where it falls, or even informing anyone whosoever of the spot where he went to throw it (in the case of a check book or a credit card, it must be given back to the bank). This gold or money that was not worthy to be accepted can be eventually handed over to the persons in charge of the monastery or to the association that administers it, but in no way to a kappiya.

Note: This rule corresponds partly with the last of the ten precepts.

nissaggiya 19

"yo pana bhikkhu nānappakārakaṃ rūpiyasaṃvohāraṃ samāpajjeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to use money. If a bhikkhu uses gold or money or other monetary means to proceed in the exchange of anything whatsoever, he must abandon all that which was thus obtained and it entails a pācittiya.

Note: This rule corresponds partly to the last part of the ten precepts.

nissaggiya 20

"yo pana bhikkhu nānappakārakaṃ samāpajjeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to exchange things. If a bhikkhu proceeds in an exchange, to a purchase or a sale (by means of any materials whatsoever), the object purchased in this way must be abandoned and it entails a pācittiya.

However, he can proceed in this exchange with other bhikkhus, bhikkhunīs and sāmaṇeras (only if this is done to help one another and not to engage in business).

3rd part, patta

nissaggiya 21

"dasāhaparamaṃ atirekapatto dhāretabbo. taṃatikkāmayato nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to keep an extra bowl more than ten days at a time. If a bhikkhu, during a period exceeding ten days, keeps a bowl, in addition to the one that he determined as his bowl, this extra bowl must be relinquished and it entails a pācittiya.

Without determining and abandoning it, an extra bowl can be kept only ten days at the most. Beyond that limit, it must be relinquished to another bhikkhu. In this case, the bhikkhu utters this formula:

"ayaṃ me bhante patto dasāhātikkanto nissaggiyo, imāhaṃ āyasmato nissajjāmi."

"This extra bowl that I kept more than ten days must be relinquished. Venerable, this bowl, I abandon it to you."

Once this relinquishment is done, the bhikkhu, while accepting the bowl, must remit back to the guilty bhikkhu, who should either determine this bowl, or else definitely abandon it to another bhikkhu.

nissaggiya 22

"yo pana bhikkhu ūnapañcabandhanena pattena aññaṃ navaṃ pattaṃ cetāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ, tena bhikkhunā so patto bhikkhuparisāya nissajjitabbo. yo ca tassā bhikkhuno padātabbo "ayaṃ te bhikkhu patto yāva bhedanāya dharetabbo" ti, ayaṃ tattha sāmīcī."

Not to ask for a new bowl as long as the present one does not have at least five cracks or has not become unusable. If a bhikkhu asks – and receives – a new bowl, while the previous doesn't have at least five cracks or fissures, or hasn't become unusable yet, it must be relinquished and it entails a pācittiya. This bowl must be relinquished to the saṃgha (all the bhikkhus of the monastery) by remitting it to the eldest among the brethren. In turn, the eldest remits one of his bowls to the second bhikkhu (in rank of seniority) who will remit one to the next and so on. The worst bowl – which is extra to all others – must be remitted to this guilty bhikkhu who will have to utilise it until it breaks. He must also relinquish his original bowl. To give up the new bowl, the guilty bhikkhu will say:

"imaṃ me bhante patto ūnapaṅca bandhanena pattena cetāpito nissaggiyo, imāhaṃ saṃghāssa nissajjāmi."

"Venerable, it is convenient that I give up this bowl that I asked for, knowing that mine doesn't bear five cracks yet. This bowl, I leave it to the saṃgha."

Once this bowl has been abandoned, the bhikkhu must purify the pācittiya by doing the desanā.

If the crack of an earthen bowl has a length measuring at least two phalanxes, a small hole must be punctured on each side so that a string, being utilised as fixation, could pass through. If the bowl does not have at least ten phalanxes, a new bowl cannot be claimed. If there are holes where food can be stuck in, they must be sealed with graphite or resin. If a grain of semolina can pass through a hole, the determination of the bowl is abolished; it means that the bowl can no longer be considered as such. And so, if a hole is enlarged, it must be sealed with the help of a sheet, or an iron filing, etc.

Naturally, a bhikkhu can accept a supplementary bowl if a dāyaka offers it to him spontaneously, even if the present bowl is still in good shape.

nissaggiya 23

"yāni kho pana tāni gilānānaṃ bhikkhūnaṃ paṭisāya nīyāni bhesajjāni, seyyathidaṃ, sappi navanītaṃ telaṃ madhu phāṇitaṃ, tāni taṭiggahetvā sattāharamaṃ sannidhikārakaṃ paribuñjitabbāni. taṃ atikkāmayato nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to keep medicinal foods more than seven days at a time. If a bhikkhu undergoing a stage of bad health, who is allowed to store and use medicinal foods such as butter, fat, oil, honey, molasses or sugar for a period of seven days at the most, consumes one of these stored foods after this period, the product must be forsaken and it entails a pācittiya.

These medicinal foods must be accepted within the limits of what can be consumed during a period of seven days. If these medicinal foods cannot be totally consumed during this period, before the seven days have expired, the bhikkhu must make a determination by saying: "I will eat - or drink - no more of this product." If this (or these) food (s) is not absorbed but only smeared, it can be stored beyond seven days. It is improper to consume these foods if it is only due to hunger or to simply satisfy a desire (gluttony). These medicinal foods are only permitted in the following cases: lack of energy, weakness, illness due to winds circulating in the body and other health problems of this kind. A bhikkhu suffering these health problems is free to use these products at any moment of the day or night.

Among the five types of medicinal foods, those that are consumed must be filtered prior to it, to make sure that they do not contain any solid particles. Nowadays, apart from sugar cane, all that is extracted from sugar such as palm juice, cubes of palm sugar and molasses of palm (usually in the shape of irregular balls) also belong to the category of honeys, sugars and molasses. Sick bhikkhus are allowed to use sugar cubes and hard molasses. As to the bhikkhus who do not have health problems, in case of hunger, they are allowed to consume sugars or molasses in the afternoons,. However they can do it only in liquid form.

A healthy bhikkhu must give up this type of liquid the same day and cannot accept solids in the afternoon. At the end of the seven days, an unhealthy bhikkhu must abandon and get someone to re-offer him these products if he needs to be able to consume them for another seven days.

nissaggiya 24

" " māso saso gihmāna" nti bhikkhunā vassikasāṭikacīvaraṃ pariyesitabbaṃ, "addhamāso seso gihmāna" nti katvā nivāsetabbaṃ. orenace "māso seso gihmāna" nti vassikasāṭidacīvaraṃ pariyeseyya, ore "na ddhamāso seso gihmāna" nti katvā nivāseyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to get a bath robe, sewed, dyed or brought before the full moon. If a bhikkhu searches for a material to make a "bath robe" between the full moons of October and May, if he sews or dyes a "bath robe" between the full moons of October and June, or if he determines or wears one between the full moons of October and July, he must abandon this robe and it entails a pācittiya.

A "bath robe" is a material worn by a bhikkhu while taking his shower under the rain (during the monsoon, between June and October).

The bathrobe nissaggiya must be relinquished to the saṃgha, or to a group of bhikkhus, or to a single bhikkhu. Afterwards, the pācittiya must be purged by means of desanā. Here is the formula that must be pronounced either in pāḷi, or else in another language, when the "bath robe" is abandoned.

"idaṃ me bhante vissikasāṭikacīvaraṃ atirekamāse sese gihmānepariyiṭṭhaṃ, atirekaddhamāse sese gihmāne katvā paridahitaṃ nissaggiyaṃ, imāhaṃ saṃghāssa nissajjāmi."

"Venerable(s), I must abandon this bathrobe that I searched for and obtained outside the five authorised months / which I sew, dyed, wore beyond the four authorised months. This robe, I leave to you."

Afterwards, the bhikkhu must abandon this robe.

nissaggiya 25

"yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhusa sāmaṃ cīvaraṃ datvā kupito anattamano acchindeyya vā acchindāpeyya vā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to take back a robe after having offered it. If a bhikkhu, after having offered a robe to another bhikkhu, out of anger, or else out of annoyance, takes back this robe or causes someone else to take it back, this robe must be forsaken and it entails a pācittiya.

A bhikkhu who takes back a robe that he has offered to another bhikkhu, while considering it belongs to him, commits the nissaggiya 25. If the first bhikkhu takes back something that he gave to a second bhikkhu and the latter knows that this thing was given to him, depending on the value of the object, the first bhikkhu may commit the pārājika 2. In all cases, the robe must be given back to its owner.

nissaggiya 26

"yo pana bhikkhu sāmaṃ suttaṃ viññāpetvā tantavāyehi cīvaraṃ vāyāpeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to get the robe woven. If whilst asking for thread, a bhikkhu gets a robe woven and he receives it, he must abandon it and it entails a pācittiya.

A bhikkhu must not ask for a large quantity of thread from a person who is not a relative of his or who has not invited him to tell what he needed. If a bhikkhu causes one of these persons to get a robe woven by a weaver, he commits the nissaggiya 26.

nissaggiya 27

"bhikkhuṃ paneva uddissa aññātako gahapati vā gahapatānī vā tantavāyehi cīvaraṃ vāyāpeyya, tatra ceso bhikkhu pubbe appavārito tantavāye upasaṅamitvā cīvare viappaṃ āpajjeyya "idaṃ kho āvuso cīvaraṃ maṃ uddissa viyyati, āyatañca karotha vitthatañca appitañca suvītañca suppavāyitañca suvilekhitañca suvitacchitañca karothi, appeva nāma mayampi āyasmantānaṃ kiñcimattaṃ anupadajjeyyāmā" ti. evañca so bhikkhu vatvā kiñimattaṃ anupadajjeyya antamaso piṇḍapātampi, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to ask for a robe to be woven bigger and of better quality than the one that the donor had planned to give. If, after a dāyaka has requested a weaver to weave a robe for a bhikkhu who is not a relative of his, without being requested to do so, the latter proceeds to a weaver to give him instructions so that the woven robe is of better quality than the one that the donor has planned to give, and according to these instructions, the weaver makes it larger; or else thicker; of better quality; regular and flat; or he spreads the material or dyes the thread well, if he gets this robe woven according to his wish, it irremediably calls for its forfeiture, and it entails a pācittiya.

nissaggiya 28

"dasāhānāgataṃ kattikatemāsikapuṇṇamaṃ bhikkhuno paneva accekacīvaraṃ uppajjeyya, accekaṃ maññamānena bhikkhunā paṭiggahetabbaṃ. paṭiggahetvā yāva cīvarakālasamayaṃ nikkhipitabbaṃ. tato ce uttari nikkhipeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to accept any extra robe – offered or not out of emergency – beyond the authorised period. If a bhikkhu accepts an extra robe that is offered or not because of an emergency, and he keeps it beyond the authorised period (refer to nissaggiya 3), it must be relinquished and it entails a pācittiya.

As an exception, a bhikkhu can accept an extra robe as soon as ten days before the end of the vassa, in case of emergency. A robe that is offered urgently is a robe offered by: a person who must leave on a trip; a pregnant woman; a sick person or a person whose faith in the dhamma suddenly arises. This donor can then invite the bhikkhu so as to offer him, or can himself go to the bhikkhu, and tell him: " vassāvāsikaṃ dassāmi." In English: "I offer you this robe of vassa." In these conditions (of emergency), the bhikkhus are authorised to accept a robe. If this robe is accepted before the kathina, it can be stored as a supplementary robe until the full moon of November (or beginning of December), that is to say, a month before the end of vassa. If this robe is accepted after the kathina, without determination, it can be stored during five months starting from the end of the vassa. If it is kept beyond the maximum authorised period, in both cases, it entails the nissaggiya 28.

nissaggiya 29

"upavassaṃ kho pana kattikapuṇṇamaṃ yāni kho pana tāni āraññakāni senāsanāni sākaṅkasammatāni sappaṭibhayāni, tathārūpesu bhikkhu senāsanesu viharanto ākaṅkhāno tiṇṇaṃ cīvarānaṃ aññataraṃ cīvaraṃ antaraghare nikkhipeyya, siyā ca tassa bhikkhuno kocideva paccayo tena cīvarena vippavāsāya, chārattaparamaṃ tena bhikkhunā tena cīvarena vippavasitabbaṃ. tato ce uttari vippavaseyya aññatra bhikkhu sammutiyā, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to leave one of the robes more than six nights in a village, at the end of the vassa period, while lodging in a dangerous area. If, during the kathina, a bhikkhu who is not sick, leaves one of his robes in a village for more than six nights, this robe must be abandoned and it entails a pācittiya.

During the kathina, if a bhikkhu living in a forest monastery fears a danger, he can leave one of his robes in a village for a period of six nights (at the most).

According to this rule, four conditions must be fulfilled to be permitted to leave a robe in a village:

- The bhikkhu has completed his vassa.

- The period – of the deposit of the robe – takes place during the kathina.

- The dwelling of the bhikkhu is located at least two thousand cubit lengths – approximately a kilometre/ (0.62 miles) – from the village.

- The bhikkhu fears to lose his robe.

nissaggiya 30

"yo pana bhikkhu jānaṃ saṃghikaṃ lābhaṃ pariṇataṃ attāno pariṇāmeyya, nissaggiyaṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to divert for his own benefit a donation made to the saṃgha. If, coming to know - by means of gestures or speech - that some things were meant to be offered to the saṃgha, a bhikkhu succeeds in getting them diverted to him for his own benefit, these things must be forsaken and it entails a pācittiya.

This rule specifies that even a bhikkhu who accepts things that his mother meant to offer to the saṃgha, after having influenced her to divert them to him, commits the nissaggiya 30.

The 92 pācittiyas

1st part, musāsāvāda

pācittiya 1

"sampajānamusāvāde pācittiyaṃ."

Not to lie. If a bhikkhu utters false speech whose nature he is aware of, he commits a pācittiya.

A bhikkhu who knows that what he has said is wrong only after having said it, if he doesn't rectify his speech, he immediately commits the pācittiya 1. The bhikkhu who gives erroneous talks, believing them to be right, does not commit any fault.

While asserting, with full knowledge of the facts, that something is true when it is not, or else that it is not true when it actually is, by making this wrong information known by means of body (gestures, hand writing) or speech, it is considered as a lie.

Note: This rule corresponds with the fourth of the ten precepts.

pācittiya 2

"omasavāde pācittiyaṃ."

Not to insult another bhikkhu. If, by means of abusive words, a bhikkhu verbally offends another bhikkhu, he commits a pācittiya.

pācittiya 3

"bhikkhupesuññe pācittiyaṃ."

Not to create disagreement between bhikkhus. If a bhikkhu deliberately provokes a disagreement between bhikkhus, he commits a pācittiya.

The simple fact of making a report of hostile talks can create a disagreement.

pācittiya 4

"yo pana bhikkhu anupasampannaṃ padaso dhammaṃ vāceyya, pācittiyaṃ."

Not to recite together with laymen, texts of dhamma in pāḷi. If a bhikkhu recites pāḷi texts taken from the tipiṭaka or authoritative commentaries on them, even short extracts, together with laymen or laywomen, sāmaṇeras or sīladharas, he commits a pācittiya.

By reciting together with such classes of people, texts in pāḷi or texts from dhamma in other languages, a bhikkhu does not commit any fault. By reciting together text from the dhamma in pāḷi with other bhikkhus or with some bhikkhunīs, a bhikkhu does not commit a fault.

pācittiya 5

"yo pana bhikkhu anupasampannena uttari dirattatirattaṃ sahaseyyaṃ kappeyya, pācittiyaṃ."

Not to spend the night under the same roof as the laity. If bhikkhu spends more than three nights under the same roof and between the same walls as a layman or a sāmaṇera, he commits a pācittiya.

In this context, when we speak about "spending the night", it is the simple fact of lying down at dawn time, - as soon as the first light of dawn appears in the sky once the night is over - which is taken into consideration. Thus, a bhikkhu who spends more than three nights with a layman, if he gets up before dawn by the fourth night, he does not commit a fault.

A bhikkhu commits the pācittiya 5 if he spends more than three nights under the same roof and between the same walls as a person who is not a bhikkhu or with an animal with which it is possible to commit the pārājika 1. If a bhikkhu spends more than three nights under the same roof but not between the same walls as a layman (that is to say in another room), he commits a dukkaṭa but not a pācittiya.

A bhikkhu who spends more than three nights in the same building as a layman, but who remains in a room that does not share a common entrance way with the one where the layman dwells (in such a way that if the layman wishes to enter the room of the bhikkhu, he is first compelled to proceed outside), does not commit the pācittiya 5.

pācittiya 6

"yo pana bhikkhu mātugāmena sahaseyyaṃ kappeyya, pācittiyaṃ."

Not to lie down in a building in which there is a woman. If a bhikkhu lies down in a building where there is at least one woman - under the same roof and between the same walls - he commits a pācittiya.

For the pācittiya 6 to be committed, a woman must also be lying down (with the head lying). For example, if a bhikkhu sleeps lying down in a room where there are several women who are all standing or seated without the head resting on the floor, he does not commit this pācittiya.

If a bhikkhu lies down under the same roof as a woman but not between the same walls - in a different room - he commits a dukkaṭa but not the pācittiya 6. If he lies down at an upper floor of the building, and the woman is at the ground floor and this floor does not communicate with the upper floors, he does not commit a fault. If this building has an inner staircase - which interconnects the two levels -, the bhikkhu commits the pācittiya 6 (except if he is in another room).

"Lying down" means to have the head resting; whether on the floor, a bed, or else a pillow, armrest, etc. The pācittiya 6 is committed every time the bhikkhu lies his head. If the head is not lying down, a bhikkhu can sleep seated with the head leaning, in the same room as a woman, without committing this pācittiya. Sick bhikkhus are not exempted from the pācittiya 6.

pācittiya 7

"yo pana bhikkhu mātugāmassa uttarichappañcavācāhi dhammaṃ deseyya aññatra viññunā purisaviggahena, pācittiyaṃ."

Not to teach to a woman more than six consecutive words of dhamma. If, not being in the presence of a man able to understand, a bhikkhu teaches a woman more than six consecutive words of dhamma (tipiṭaka or authoritative commentaries on them) in pāḷi, he commits a pācittiya.

If the bhikkhu uses another language, he can freely teach the dhamma to women. By pronouncing in pāḷi, the sentences of taking refuge in the triple gem or the precepts, there is no fault. The reason for this being that it was not meant to make known the points of the dhamma.

According to this rule, a series of words means a verse, for the texts composed in the form of stanzas. Concerning texts devoid of a particular structure, each word is considered as a continuation of the preceding one.

A bhikkhu, when in the presence of several women, can teach six consecutive words of dhamma to each one, even if the others listen. As soon as the bhikkhu or the woman changes his or her position, the bhikkhu can teach six supplementary continuations (to the same woman) without being at fault.

pācittiya 8

"yo pana bhikkhu anupasampannassa uttarimanussadhammaṃ āroceyya, bhūtasmiṃ pācittiyaṃ."

Not to announce to a layman a realisation that has been achieved. If a bhikkhu announces to a layman or to a sāmaṇera, a realisation partaking with a jhāna nature or with a stage of ariyā, and this realisation has genuinely been achieved, he commits a pācittiya.

On the other hand, a bhikkhu who makes such a declaration, while knowing it to be false, commits the pārājika 4. A bhikkhu must avoid making his attainments known, even to other bhikkhus. Apart from four exceptions when they can do so, ariyās never unveil their realisations:

- Under a violent threat.

- Undergoing an oppressive and virulent lack of respect.

- A t the time of passing away.

- To reveal it to his preceptor or to a fellow bhikkhu who does a similar practice.

pācittiya 9

"yo pana bhikkhu bhikkhussa duṭṭhullaṃ āpattiṃ anupasampannassa āroceyya aññatra bhikkhusammutiyā, pācittiyaṃ."

Not to denounce a saṃghādisesa to a layman. If, without permission from the saṃgha, a bhikkhu reveals to a layman or to a sāmaṇera a saṃghādisesa that another bhikkhu has committed, he commits a pācittiya.

To dissuade the bhikkhu who has committed a saṃghādisesa from doing it again, one or several bhikkhus could reach an agreement resulting from a meeting of the saṃgha, allowing them to openly announce this saṃghādisesa to the people. However, any bhikkhu can freely announce the saṃghādisesa committed by a bhikkhu to another bhikkhu or to a bhikkhunī.

By announcing to a layman or to a sāmaṇera that which the bhikkhu has committed without specifying what kind of fault is involved or by mentioning which category the fault being committed belongs to, without expressly specifying what was committed, a bhikkhu does not commit any fault.

pācittiya 10

"yo pana bhikkhu pathaviṃ khaṇeyya vā khaṇāpeyya vā pācittiyaṃ."

Not to dig or cause someone else to dig the earth. If a bhikkhu himself digs or causes someone else to dig for him some "real earth", he commits a pācittiya.

By digging, explosion, scratching, lighting a fire or by any other means whatsoever, a bhikkhu must, in no case at all, modify the earth in any shape whatsoever. Also, he cannot cause the earth to be dug by someone else by directly asking him to do so. However, he is authorised to make him indirectly understand, by telling him for example: "I inform you that there is some earth that needs to be moved."

Two types of earth are distinguished; the "real earth" and the "false earth". Earth that is on its original place is considered as the "real earth", and earth that has been moved is considered as the "false earth". When the latter has been humidified by four months of monsoon, it then becomes "real earth". A bhikkhu who digs or causes some "false earth" to be dug by someone else, does not commit any fault, whereas by digging or by causing some "real earth" to be dug by someone else, he commits the pācittiya 10.

The various qualities of earth are also taken into consideration. If the earth that is dug is situated in the depths or if it is some relatively pure or pure earth, the bhikkhu commits the pācittiya 10. However, if it concerns earth containing pebbles or fragments of pottery, the bhikkhu can dig or cause someone else to dig it without being at fault.

2nd part, bhūtagāma

pācittiya 11

"bhūtagāmapātabyatāya, pācittiyaṃ."