The Scientific Outlook Of Buddhism

By Wang Chi Biu

English Translation By P. H. Wei

Introduction:

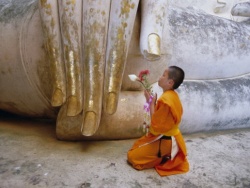

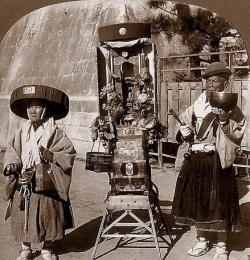

Buddhism, that oldest world religion, is generally misconceived to be a blind faith. As seen from its outward appearance, really it is painted with a strong religious color. To a non-Buddhist, who sees the golden image of Buddha, and hears the chanting of Sanscrit Sutras and the clinking of the bell, Buddhism is nothing but idolatry; in view of their passive life, Buddhists of the Order are said to be "social parasites". However, on the contrary, whatever is expounded in Buddhism, down to every minor matter, is based on the Teaching of Buddha. Indeed, some of the Buddhist principles are too profound to be easily explained and understood by the lay people, except those of high intellect. Without making a serious effort to study the issue in question, those who say what others say, and believe what others believe, that Buddhism is a superstitious faith, betray not only their ignorance of its fundamental principles but also their lack of common sense and understanding; therefore, in regard to Buddhism, what they say and what they believe cannot but be blind and untrue.

Depending in what sense Religion is defined, Buddhism may be called Religion or non-Religion. If religion refers to Monotheism or Polytheism, then Buddhism, being non-theological, is no religion at all. If religion, broadly defined, refers to some School of Teaching, Buddhism in that sense may be said to be in the same category as Confucianism and Taoism.

In the wake of the remarkable development of modern Science, the monotheistic and polytheistic religions of the world are open to scientists’ attack rather helplessly, but Buddhism stands out as unique exception to this. It is because the more advanced is Science, the more and the better is Buddhism understood. In the meantime, in parallel to the stupendous scientific achievements of this age. Buddhism spreads more and more to the world. In China, at one time some engineers and scientists were not only devout Buddhists but also conversant with Buddhist Scriptures. This is an eloquent proof that Buddhist theories can be tested and corroborated by science. In reality, the more learned the scientist is, the easier and the better can he comprehend the difficult Buddhist terms and the profound theories of Buddhism. Thus he would come to realize that whatever phenomena, physical or psychical, as explained by Buddha, far from being superstitious, are all based on Reason and reality only. In the light of this understanding, the writer was prompted to present to readers "The scientific Outlook of Buddhism."

Chapter 1

Buddhism is Absolutely a Rational Religion

Buddhism is an experimental intelectual product, like science. In view of this similarity between the two, it may be safely assumed that rather by science, than by Philosophy, Political Science, Economics or Literature, Buddhism can be better understood. Inasmuch as science has broken down the walls of ignorance and liberated mankind from the fetters of delusion since thousands of years ago, Buddhism also has made its significant contribution to humanity towards the same end. Some salient characteristics of Buddhism may be mentioned in the following to show where it is established absolutely on rational basis.

(A) To Remove Ignorance

Usually we are subjected to various sorts of illusion in daily life and unless detected by reason and awareness, they may remain with us and lead us to make errors once and again. For instance, in the old days it was generally held that the earth was flat, square and standing still while the sun was in motion; later this conception was refuted by scientists and proved fallacious. Again, eclipses of the sun and the moon were looked upon by the ignorant people to be something very mysterious, but today not only we are familiar with the sun eclipse to be caused by the moon and the moon eclipse to be due to the shadow of the earth, but when such incidents may take place can be known precisely by mathematical calculations. In Geometry many examples of illusions may be found. If two lines of same length are put in parallel with each other, with bracket sign appended to both ends of each line, likely we would be under the illusion that one line is longer than the other. From this, it shows that usually we cannot tell exactly the length of a thing merely by our eyes. Again, as pointed out by astronomers, it is fallacious to assume that those stars before us are existent, because they are so far from the earth that the distance between the two may be calculated in terms of Light Years only (each Light Year calculated by this formula: 300,000 miles per second multiplied by the number of seconds of one Calendar Year), thus some of those stars may be as far away from the earth as several ten Light Years; in such cases, most likely what we see are not stars but only their lights issued as far back as several decades ago and, where they are now, scientists can hardly know. Again, in our general conception, tables, chairs, cups, etc., in the house are solid and motionless, but according to physicists, the atoms of those hard objects are similar to the Solar System, with electrons rotating around atomic nuclei at the rate of Light Speed and also with adjoining atoms vibrating all the time, thus considerable spaces between electrons and atomic nuclei, and those between the adjoining atoms are left empty to a large extent; of course, such interior phenomena of those things and their outward appearances are entirely different from each other. This shows that owing to the illusion of the eyes, the reality of everything cannot be correctly perceived, and it is only by logical inference that illusion may be rectified and correct perception may be possible.

In the pre-science days many errors of illusion were rectified by Buddhism. Refuting the old Chinese saying, "there are no two suns in Heaven", the Sutra says: "In the Great Trichiliocosm, there are as many as ten billion suns." This statement, astounding as it is, is in accord with Astronomers’ discovery that all those densely-clustered stars in the space and everyone of them are affiliated with the Solar System. Whereas in the Chinese poetry the moon is described "full" of "partial", the Sutra says the moon is "bright", "clear", "dim", or "dark", and this is not only free of visual illusion but also in line with the scientific theory of the moon reflecting on the sun. Again, one who is ignorant of Biology would assume that the "self" is the sole possessor of the body, but, in fact, inside the body, there reside innumerable cohabitants of living germs. As far back as 2500 years ago, Buddha made this assertion: "Human body is but a swarm of worms which may be enumerated into eighty kinds." (Refer to The Secrets of Remedy for Chan Ills Sutra). In the Sutra not only those worms are differentiated by their specific names but also their behavior and activities are described in details. Again, the Sutra says: "As seen by the Buddha, a drop of water contains 84,000 germs." In those prescience days when the aid of scientific apparatus was nil, it was exceedingly difficult for Buddha to make his exposition of this scientific truth understood by his people, notwithstanding their implicit confidence in what he said of himself in the following words: "The Tathagata speaks the truth, speaks in concrete words, speaks of reality as it is, speaks no lies and no contradictions." Of course, those biological facts, revealed by Buddha, can be easily verified by science today.

Before Algebra was introduced in schools, people had very imperfect knowledge of Mathematics; apart from integrals, they knew nothing of negative and zero, and still less, the Imaginary Number. In contrast, Buddhist conception of everything is complete and all-inclusive. To illustrate, when the body is in touch with a thing, there is the feeling of Touch, and when it is not, there is the feeling of Non-touch; if one is used to be unaware of the latter, he would become indifferent to the former as well. To classify feelings of Touch and Non-touch may be said to be similar to the numbers of Integrals and zero in Algebra. Again, in Buddhism, sensation of pleasure, sensation of pain and neutral sensation (neither pleasure nor pain), are as differentiated from one another as integrals, negative and zero are in Algebra. Besides "good" and "evil", there is the "indefinite" which is neither good nor evil. All this shows that Buddhism is complete and all-embracing, and in some respects, apart from being in accord with the scientific spirit, is above the common sense.

The Theory of soul is repudiated by both Buddhism and Science. The reason why believers upholding this theory is this: as human body is made of flesh and other material things, all of which are without consciousness, the need of a conscious being to be its master is obvious, same as a motor car in need of a driver. According to this theory, when one is alive, the soul is inside the body, but at the time of one’s death, it departs from the body. Apparently, this sounds plausible, but if tested by Logic or Hutuvidya, the Science of Cause, its fallacy is perceived at once. Let us ask this question: Is the soul material or immaterial? If it is a material thing inside the body, why has it remained unknown to mankind without being discovered by Science of Anatomy even to the present day? The assumption that it leaves the body after one’s death is illogical, because no material can move by itself; and if it is sent out by the heat of the body, it should be found around the body. Again, since both the soul and the body are material things and both of them are without consciousness, to say that the one needs the other to be its ruler is utterly pointless. Therefore, to say that the soul is material is a fallacious statement. On the other hand, to say that it is immaterial is also fallacious, for if it can move in and out of the body, it is no longer immaterial.

Now that the concept of soul is refuted by Buddhism, we may ask, "What is THAT which rules over oneself during one’s lifetime and is subjected to reincarnation after one’s death?" Here is Buddhism’s answer: THAT may be expediently called either Consciousness or Buddha-nature and is the Essence of everything; it is immaterial and formless, neither inside nor outside the body, neither entering nor departing from the body. Consciousness is Essence contaminated with material craving and passionate vexation, and Buddha-nature is Essence pure and undefiled; in reality, Consciousness and Buddha-nature are but two aspects of one substance. Of course, Consciousness or Buddha-nature is essentially different from the soul, which is said to be of material form, abiding inside the body and capable of moving in and out. Despite that Consciousness or Buddha-nature is without these physical attributes of the soul, nevertheless, if and when conditions are ripe, it may transform itself into a material form to enter or to depart from the body. In view of this, it is said to be neither material nor immaterial. Now to return to the above question. Without being able to give any answer at all, the scientist merely says arbitrarily, "There is nothing like that." Buddhism tells us, however, that it is only by direct apprehension of the reality and by self-experiencing, as resorted to by Buddha, that truth and illusion may be perceived and the good and the evil may be clearly discerned; in the meanwhile by the various Dharmas of cultivation, we would be able to verify truth by ourselves, after the manner of Buddha’s self-experiencing.

Indeed, Buddhism and Science are two brilliant lamps of the world, and it is by their illuminating power that ignorance and superstition would be eliminated, biased views and dogmatism would be eradicated and infinite progress would be made by human beings in exploring human wisdom till the attainment of Supreme Enlightenment. It must be conceded, however, that no matter how progressive and advanced is its development, science is largely confined to the study of material phenomena, but to understand the reality of those phenomena where mind is involved, we cannot but depend on Buddhism, and Buddhism only. For instance, nowhere among those books of Western Psychology can we find such inexhaustive and analytical study of the psychological aspects and reactions of the various sense-organs of human beings as enunicated in the Sastra on the Hundred Divisions of Mental Qualities.

On hearing a musician playing a famous piece of music, not only we can tell its melody by Ear-Consciousness and its tune by Sense-center Consciousness, but various kinds of imagination would stir up and sensation of enjoyment and craving would arise automatically (according to Dharma-laksana sect, in such psychic phenomena the following Mental Associates would be brought out into play: touch, volition, sensation, conception, desire, greed, stupidity and indolence). This case refers to people with musical training. If it is played to someone ignorant of music, the tune and the melody notes are but packages of noises and his reaction would be a feeling of disgust instead of pleasure. Again, to a physicist, music is nothing but a series of air waves with chords and curves of various frequencies (simple harmonic vibrations), and actually this corresponds with the way the eardrum responds to the sympathetic vibration of air waves. According to his conception, on the sine curves there is neither melody from Ear-Consciousness nor there is tune from Sense-center Consciousness at all, and still less, the feeling of like and dislike. In short, the vital fact is often overlooked that whatever differentiations and reactions caused by Ear-Consciousness and Sense-center Consciousness are usually misconceived to be something of the air waves, and without our being aware of our illusion, we are used to say the song is "pathetic" or "beautiful", as if these were the qualities of the song. This shows our greatest error of illusion : [To Perceive the Unreal as Reality). Therefore, Buddhism expounds this fundamental principle that every phenomenal change is made by consciousness only. Let us take another illustration. To one who likes onion, it smells good, and for another person who dislikes it, its smell is repulsive. However, if in reality it is of one smell, it should not vary with different persons.

(B) To Let Go Emotions

To help us discover our various sorts of illusion and to rectify them by reasoning so as to enable us to proceed progressively towards the Path of enlightenment may be said to be the professional work of Buddhism. For this reason, Buddhism is said to be absolutely rational: not only it is unmixed with, but also free of, every sentiment, and in this respect, is completely identical with Science. Though Philosophy is also established on rational basis, it cannot be gainsaid that among those different schools of Philosophy, as far as their theories are concerned, there is no lack of biased views, dogmatism and subjectivity. This also holds true with other subjects of Social Science. Literature and Arts, where sentiment plays the predominating role, and where sentiment is strong, reasoning is weak, this is why, since thousands of years ago the work to make correct evaluation of Literature and Arts has been rather difficult. Feeling and reason usually and mutually counteract each other; when emotion gets the upper hand, reason flies out of the head, and when reason prevails, such feelings as fear, craving and so forth all give way. Parental love is a natural feeling but if it is carried to excess, one would not be able to understand the youngsters and their conduct correctly. Again, if patriotism bursts out for no cause, it would become chauvinistic, fanatic and calamitous. If male and female, desperately in love with each other, are unable to overcome obstructions standing in the way, they would lose their head and do such foolish thing as to commit suicide. In the eyes of Buddhism, all these private and public feelings, because they are overdone, are foolish and blind love, therefore on no account should we allow emotions to get the better of us. Thus, the Surangama Sutra says: "The reason why sentient beings may ascend or descend at the six levels of Transmigration is this: if emotion prevails, they would to go heaven; if there is emotion without conception, they would go down to hell; if there is half emotion and half conception, they would be born as human beings."

The critical attitude of the scientists is absolutely unsentimental, impersonal and with strong accent on the power of imagination. In view of the inadequate visual power of human eyes, we have to depend on our imagination to help us visualize the structure of atoms, the movement of the Celestial Body, transmission of electric waves, and the complicated structures of various scientific instruments. Projective Geometry, for example, is a subject where most far-fetched imagination is required.

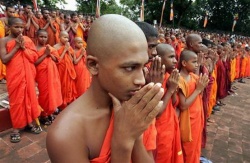

In Buddhism a good many Dharmas under the general heading of Ch’an Meditation take to imagination as a means of cultivation. The Five Meditations are a case in point: 1. Meditation on impurity of the body, 2. Meditation on Breathing, 3. Meditation on Compassion, 4. Meditation on Causality, and 5. Meditation on either the six levels of Transmigration of the eighteen Spheres. Besides, there are "Meditative Insight into the Unreality of all things", "Complete and Immediate Meditation", "Meditation on Mere-Consciousness", "Meditation on the Ten Realms", and as pointed by "Meditation on Amitabha Sutra", the Sixteen Meditations. According to the last-named Meditations, some of them are concerned with the principles of Buddhism and some with material phenomena. In the Meditation on impurity, the object of meditation is the structure of the human body, and in "the Nine Meditations", the process of decomposition of the dead body is meditated upon. Of the Sixteen Meditation, the First One is meditation on the setting of the sun at the western Paradise, and if the image can be clearly perceived whether with eyes opened or closed, the meditation would be considered well done. In the subsequent meditations from the Second to the Last ones, the objects of meditations are the people and things of the Supreme Happiness Buddhaland. To practise those Meditations calls for a high degree of imagination and so corresponds with the principle of Projective Geometry. Because he had had training in the study of Projective Geometry at school, the writer had experienced little or no difficulty in practising the First Meditation on the setting sun. This was corroborated by a distinguished Chinese Mathematician, the late Dr. Wong Chi-Tung, who used to practise the First and the Second Meditations with the most gratifying results. At all events, whatever meditation one may practise, intensive training of concentration and imagination is of fundamental importance on no account should such feeling as craving, fear, despair, disgust, etc. be allowed to enter into the meditator’s mind, otherwise one would run the risk of going the Devil’s way.

(C) To Establish Right Belief

"Buddhism is not a superstitious faith but a rational belief derived from wisdom", said the late Mr. Liang Chi-Chao, a veteran celebrated Chinese scholar. By Buddhist belief it is meant that the essence of a theory, though not yet verified by oneself, can be inferred by reasoning to be valid truth; in this sense it is at variance with the beliefs of other religions which enter on entirely different objects. What Buddhists believe is this: because Buddha-nature is inherent in every one, all sentient beings can become Buddha; Buddha-nature may manifest itself in everything, and neither becoming nor annihilating, is fundamentally pure and intrinsically immutable; inasmuch as every thing or every incident is dependent on combined causes and conditions, it has no self-nature of its own, is nothing but manifestation of the mind and is subjected to transformation by consciousness. The fundamental objective of Buddhism is to attain Complete Perfect Enlightenment, which is Wisdom evolving at the highest level of mental development, and also is the most progressive and the highest evolution of mankind. However, the belief held by some religion that God, the Omnipotent, is the Creator and "Father" of all humanity, and as such, has absolute authority over every one and should be absolutely obeyed by everyone, is in striking contrast with the Buddhist Belief and in effect, cannot but detrimentally undermine one’s own individuality, one’s own freedom of will and also the freedom to evolve one’s potential wisdom. As far as belief is concerned, evidently there is a world of difference between Buddhism and other religions. Buddha tells us the fundamental message: "Buddha’s virtues and Wisdom are immanent in all of you. This cannot be verified by you, because you are defiled by the Five Desires and egoistic thoughts; consequently, as long as you cannot deliver yourself from the bondage of delusion, you would be subjected to endure infinite sufferings." Once this fundamental truth that we are at par with Buddha is realized, a sense of self-respect would be enhanced, and every effort to practise spiritual cultivation to attain Complete Perfect Enlightenment would be exerted diligently. On the contrary, some religion has this to say: "God is our Creator, and has the power of rewarding or punishing us, therefore we should serve him like a master, and if we are absolutely obedient to him, we would be called his worthy children, and, after death, would be blessed to go to the Paradise." Granted ahtat as a reward for one’s own good deeds, one would go to the Paradise, but as long as he remains to be absolutely obedient to the Paternal Authority in question, how can one enjoy true equality and true freedom over there?

Apparently, intelligence – not belief – is stressed in learning science, but on closer examination, we can see that belief is an important requisite for studying science. The amount of lab. work of Physics and Chemistry, compared with the number of untested theories and principles, is said to be in the ratio of 1 to 1000, now the question arises: regarding those untested theories, should we first experiment with every one of them before we take for granted that they are all valid?, or, under the circumstances, should we accept all of them to be valid before testing them, one by one, ourselves? In fact, we can only choose the second alternative, for two reasons: firstly, because we know well enough from our study that not only those theories can stand to reason but also they are applicable and experimental; secondly, because in the history of science, neither a theory nor a scientist has ever been found to be a fraud, thus we have implicit confidence in the validity of those untested theories. From this, it can be seen that Belief is also essential to scientists: if a theory is deduced from commonly recognized principle, it should be accepted as valid. Again, as long as it is applicable to the present conditions, the validity of a theory holds good, unless contradicted by new discovery. Also, scientists firmly believe that all phenomenal transformations are subjected to the operation of the Law of Cause and Effect, and that none of them is uncaused, or cause by a Creator, or controlled by an unseen Power at all.

Similarly, Buddhists establish their belief in the same way. If, under critical study, no Buddhist principles are found to be illogical, impractical and deceptive, their validity should be accepted, despite the lack of their verification. Take the question of Buddha-nature, for example. Although in most cases Buddhists have not experienced what Buddha-nature is, nevertheless they all accept the validity of this theory, because of their belief in Buddha’s words, so the way to tackle the question of Buddha-nature is this: belief first and to follow up with practice till Buddha-nature is realized by self-experiencing. Once Buddha-nature is verified by oneself, it is immaterial whether to believe it or not. Again, the truth that one eats to satisfy hunger is known to everybody and needs no belief or persuasion. However, if some say that some kind of vitamin pills appease hunger, we should not believe then until we have learnt such effects of the pill from books or from their own experience. If no pill is available on hand or if no one has ever tried it, belief is still possible provided there are good reasons for believing. But to say that one would not go hungry merely by watching others eating, but without eating oneself, is so nonsensical that no amount of reasoning can dismiss its absurdity. Similarly, what some religionists say that thousands and thousands of sinners would be redeemed by a martyr’s death is exceedingly difficult to believe, and to believe it is nothing but superstition.

The Research Spirit of Buddhism

Buddhism teaches us not only to believe, but also to doubt, thus the Sutra says: "The greater doubt, the greater understanding, the less doubt, the less understanding, and no doubt, no understanding."

If a theory can be explained verbally or in writing, it may be believable; if it is inexplicable or inexpressible, it is doubtful. According to Ch’an Buddhism, once you are in doubt, keep it up incessantly with full attention, until at the advanced level of development, your mind is unobscured and completely clear. The research work of Buddhism is extraordinary and broadly extensive for it covers both the material and psychological phenomena of the world. Ordinarily people have the notion that scientists are the most critical people who ask mostly "Why" questions. Actually this is not ture, for scientists are not so much concerned with "Why" as with "What" questions; it is noteworthy that nowhere the bold question-word "Why" may be seen so oftentimes as in the Buddhist Texts. For example, while as Electrical Science says that particles of iron, if arranged in good order, would produce magnetism, it never asks, "why is magnetism produced?" or "why would particles of copper, if systematically arranged, not produce similar effect?" Again, science tells us that water boiled at 100 degree c. would turn into steam, but it does not explain why water should absorb the latent heat before it becomes steam nor would it ask "why is it possible for latent heat to be dormant in the steam?" Regarding Newton’s discovery of the gravitation of the earth, so far, there is still no answer to this question: "Why is the earth in possession of the gravitational force?" In view of the fact that even on material things, numerous "Why" questions have been left out by science unanswered, nor have scientists ever attempted to discuss them openly among themselves, therefore, to say that science has covered practically all the "why" questions about the phenomena of the world and that scientists have satisfactorily dealt with them all is utterly untrue. Buddhists, however, like a lion wounded by an arrow, are wiser and more courageous, for not only they would cure the wound, they would also find out who shot the arrow and why he did it. In dealing with every question, Buddhism is on the look-out for the cause; in other words, Buddhism raises the bold question "Why" every time without fail. If the vital question of life and the universe was confined to material phenomena alone, never could we arrive at any satisfactory solution at all. Therefore, it is only by studying both the spiritual and material aspects of the question that we may tackle it in the right way. Now we can see that as far as the spirit of research is concerned, science is incomparable to Buddhism.

(A) Research Methods

In science there are two research methods of Logic, namely, Induction and Deduction. Induction is to discover general laws or commonly accepted theories by inferring from the phenomenal change of a particular case or thing. On the other hand, Deduction, a priori reasoning, is to infer from general truths and proved theories to arrive at a particular theory or conclusion. Although scientists take every care to work out their experiments by these two methods, nevertheless, some conclusions reached by deductive reasoning are not absolutely reliable. For instance, in Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, the speed of movement of things was left out. Also, in the old Physics, two Laws, "Conservation of Matter" and "Conservation of Energy" were repudiated by modern science because of their fallacy. However, Mathematics, based on Deductions, are free of those errors; for in Maths. Although the way it infers general truths by deduction is different from the Buddhist Method of Direct Inference by Wisdom and Pure Mind, nevertheless, it is in conformity with direct apprehension of the reality of the world. Hence, in the eyes of Buddhists, all the theorems and conclusions of Mathematics are correct and true.

In comparison, the research methods of Buddhism are more rigid than those of science. According to Adhyatmavidya (a Treatise On the Inner Meaning of Buddhism), it is only by eliminating both vexation-and-passion-hindrances by wisdom and pure mind that the reality of all mental and physical phenomena may be clearly perceived. In order that this vital question may be more easily understood, Buddhism offers us the aid of Hetuvidya (the Science of Understanding the Cause), which incorporate Preposition, Reason and Example in tri-form of reasoning; the method of reasoning for the second form is Direct Inference and that for the third form is Comparison of the Known and Inference of the Unknown; both of these methods not only are in line with the logical reasoning of scientists, but are also accepted as general truth. Identically, the tri-statement formula of Hetuvidya corresponds to the three syllogisms of logic but in reverse order. In Hetuvidya, the first statement is the preposition, the second is the cause and the third is examples subdivided into (a) analogy and (b) opposite; in Logic, the major premise comes first, then the minor premise and the last is conclusion. For illustration, two charts are given below:

A) The Chart of Syllogism In Logic

1. The major premise: All metals conduct electricity.

2. The minor premise: Aluminum is a metal.

3. Conclusion: Therefore aluminum can also conduct electricity.

B) The Chart of Tri-statement Formul of Hetuvidya

1. Preposition: Aluminum can conduct electricity.

2. Cause: because aluminum is a metal.

3. Examples:

a) analogy: as far as they are known up to date, other metals can also conduct electricity. e.g. copper.

b) contrast: as far as they are known up to date, those things which cannot conduct electricity are non-metals. e.g. glassware.

Apart from some slight difference between the major premise and the example statement, the other parts of these two systems of deductive reasoning are correspondingly the same. However, in Chart B, examples, classified into a. analogy and b. contrast, compared with what is given in Char A, are more comprehensive; moreover, the conditional clause "as far as they are known." Indicates that the example statement is sound and flexible. On the other hand, in Chart A, the major premise is arbitrary and weak, as far as deductive reasoning is concerned; pending a conclusion whether aluminum can conduct electricity or not, to say that ALL metals can do so is illogical and contradictory. From this, it can be seen that as far as Logic is concerned, the Syllogistic Method is incomparable to Hetuvidya. In short, because of its exactitude, the research method of Buddhism is unsurpassable.

(B) Research Tools

Research tools are fundamentally important for research work of science: in view of the inadequate and limited powers of eyes, ears and the body to detect the intensity of light, sound, heat and hardness accurately, apart from the lack of a standard of visibility, audibility and sensitivity of those sense-organs to go by, scientists have invented numerous apparatus and instruments which not only can function more effectively and more extensively than the sensory organs of human beings but also can be free of errors of the subjective mind. By means of those ingenious instruments, quantitative measurements of various units may be obtainable, and from this information, not only the quantitative inter-relationships of all units may be inferred by mathematical deduction, but also the transformations of various material phenomena may be discovered. This, however, may mislead us to think that all scientific appliances are perfect and entirely free from error. No, they are not. In fact, this is the reason why scientists always do their utmost to improve appliances in every way. Here are some fundamental questions, which may be noteworthy for scientists to ask themselves: "WHO directs them to deal with the question of research tools in such ingenious manner?, and , if WHO goes wrong, what should be done to rectify the error?" Apparently, those questions are out of their mind, for so far, among themselves they have hardly gone into discussion of those hypothetical questions at all; moreover, apart from their indifferent attitude, they deem it best to let philosophers to speculate wildly, and religionists to talk devils, about it.

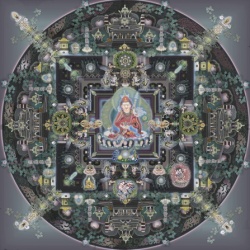

In the eyes of Buddhism, however, this fundamental question is the Fundamental Tool of all tools, and the Standard Implement of implements: it is an all-illuminating Mirror, by which all phenomena of the universe can be perceived; on the other hand, if the Tool is unworkable, or if the Standard Implement lacks accuracy, or if the Mirror is defiled with dust, then the reality of all phenomena and all things would not be correctly perceived. According to Buddhism, the Essence of mind of all sentient beings does not differ from that of Buddha, but like a dirty mirror, its function to shine does not work for the time being, thus it is only by cleaning and polishing that its bright Essence would be reverted to its original purity. All is said in the stupenduous volumes of the Tripitaka is nothing but an elucidation of different ways and means to eliminate various defilements to restore the mind to purity so that in this way the truths of life and the universe may be clearly comprehended. However, the cleaning work is by no means an easy thing to do, for not only we need the tools, but also the "Know-How" to do it well. Contrary to the conventional misconception that the Buddha’s image, the dru, the bell, flowers, pennants etc., are but symbols of superstition, we should realize that all those things and everyone of them are nothing but cleaning tools. Again, one may be seized with a sense of mystery about the odds and ends exhibited at a ritual ceremony of Tantric Buddhism in the monastery, but in Buddhism, there is no mystery at all, for, though its profound theories may not be comprehended by people generally, yet whatever it says of the phenomena and things of the world is based on Wisdom and Reason. If we observe the devotees of the Pure Land Sect zealously reciting the Buddha(chanting the name of Buddha), the serene Ch’an Buddhists sitting in meditation with one-pointed mindfulness, and devoted monks, nuns and lay Buddhists receiving Discipline and reciting sutras wholeheartedly, then we may realize that all these methods of cultivation aim to accomplish but one thing – To Clean The Mind and Keep it Clean. It cannot be too strongly stressed that there is nothing superstitious or mysterious in Buddhism; on the contrary, in Buddhism, every act, every move, and everything, come from the inflow of Purity and Wisdom of Supreme Perfect Enlightenment. Hence, Buddhism is said to be invaluable like the Mori Pearl, illuminating on all sides, but this can be realized only by self-experiencing.

(C) The Objects of Research

The Phenomena of scientific research comprise the structure of material things, changes of their movement, their mutual influence and transformations, and, as a result of these changes, their various quantitative relationships. At best, those phenomena may be said to be within the scope of a small part of the "Dharma of Matter vis-à-vis Time, Space, Speed, Graduation, etc." under the category of "Dharmas of Non-Associated Mental Activities", (see the Sastra on One Hundred Divisions of Mental Qualities) but have not touched the Dharmas of Mind and Mental Associates of Buddhism at all. Comparatively speaking, the Dharma of Matter is considerably more stagnant than the Dharma of Mind; in the sequence of its arising and passing out, thought undergoes changes so quickly and so suddenly that it is far more difficult to be aware of such changes than material transformations. Although the research of matter is comparatively easy and simple, yet scientists, by and large, cannot make a study of material transformations either separately or as a whole. If a change of a thing (A) is affected by several cause, B, C, D etc., they keep only B for research but leave out C, D, etc. altogether; in this way, the cause-and-effect relationships based on the transformations of A and B phenomena may be deduced and perceived. For example, the intensity of electric current is influenced by the voltage of electric pressure and resistance. In order to understand the relationship between electric current and pressure, the electric resistance must be kept stable without change; to understand the relationship between electric current and resistance, the electric pressure also should remain unchanged. From this, it can be seen that inasmuch as it is impossible for scientists to do their research of all phenomenal changes simultaneously, what they can best do is to simplify those complicated objects as much as possible.

The method of simplifying the research objects is also adopted by Buddhism. However, in Buddhism, the objects of research include not only material things but also the phenomena of matter and mind combined, furthermore, as the transformations of the latter are far more complex than those of the former, it is all the more necessary that Buddhism should resort to the scientific method of simplification. By the popular Dharma of Reciting Buddha, one concentrates intensively on reciting "Namo Amitabha" with unperturbed mind. Ch’an Buddhism asks us to look with undivided attention into a nonsensical and totally inexplicable question, e.g. "What is the Fundamental Face before one is born?" Likewise, other meditational practices also stress one-pointed concentration, as does the Reciting Method. Once advanced meditation is realized, the mind would be as calm as subsiding waves or would brighten up like a mirror, and then one would be able to see the reality of everything, but if one sees with a perplexed mind, then it would be a different picture altogether. A perturbed mind, like turbulent wave, can never perceive truth.

While it may do well to apply simplification method to material things, to extend its application to living beings, however, is entirely a different matter, because to research the multifarious physiological and psychological reactions would surely entail considerable difficulties. Though Anatomy enables us to know the functioning of every organism of the body, nevertheless, it is a study of a dead body, and not the body of a living being. Moreover, in the research work, apart from the complex material elements of the body, its numerous mental components should be reckoned with as well. However, as long as that being is alive, it is physically impossible to bring those material elements and mental components, or any one of them, to a halt for research of their causal relationships. If the research objects cannot be simplified, the phenomena of matter and mind combined would not be correctly perceive at all. Under the circumstances, scientists can only turn to Buddhism and its way of cultivating Meditation and Wisdom, for an answer.

Chapter 3

The Buddhist Theory of Equality

The conventional conception of equality is narrow and restricted to political, economic and educational sectors, and equality between the two sexes, but none of them deals with the fundamental question of absolute equality. In view of the manifold differences of individuals in their family background (high or low), personal appearances (good looking or ugly), disposition (gentle nature or quick-tempered), intellect (intelligent or dull), and health (strong or weak), fundamentally speaking, there can be no equality among mankind. However, such variations and differentiations, as pointed out by Buddhism, are but illusory phenomena of life, for insofar as the Essence of man is concerned, human beings are absolutely on equality with one another, According to Buddhism, equality is not fragmentary and sectional, but complete and universal. Not only between man and man, Buddha and Buddha, is there equality, but also between man and Buddha, man and animals, man and dwellers of Paradise and Hells, man and ghosts; all of them are equal with each other. Thus, the Sutra says: "Mind, Buddha and sentient beings are all at parity with one another." Furthermore, apart from this, all mental phenomena, physical phenomena, combined physical and mental phenomena, as well as causes and effects are also at par with each other. Again, the Sutra says: "This Dharma (Sammasambodhi) is in parity (with the others), and is neither superior nor inferior (to any of them)." It is because sentient beings are deluded and defiled with perverted views that they make discriminations and so they are oblivious of the Essence of Nature. In reality, the Essence of every sentient being is identical and immutable. This is the basic Principle and Fountainhead of the Complete Teaching of Buddhism.

(A) Illusory Phenomena of "Ego Personality" and "Other-Personality"

According to Buddhism, man is made up of five Aggregates, viz. Form, Sensation, Conception, Volition and Consciousness. Form is a material and the other four Aggregates are the activities of the mind. Sensation comprises feelings of suffering, pleasure, sorrow and joy. Conception is thought or imagination. Volition is mental activity for good or for evil. Consciousness is that which makes discriminations. If the physical body of man, made up of skin, hair, bone, flesh, blood and salivia, is analysised, by chemical process, it is nothing but a number of atoms of carbon, hydrogen, dioxide, phosphorus, calcium, iodine and other elements. This holds true with the body of everyone, yours and mine, and also with the body of every animal. In view of the fact that on analysis, the iron element of my body is not different from that of yours, the principle of Equality is established by deductive reasoning that as far as the material aspect is concerned, there is no difference between man and animal at all.

Let us turn to the spiritual or psychical aspect of man. Mencius (Ancient Chinese Philosopher) said: "The sense of Compassion is in everyone; the sense of Shame is in everyone; the sense of Right and Wrong is in everyone; and the sense of Humility is in everyone." This may be said to be in line with the Buddhist Theory that the four psychical functions of Sensation, Conception, Volition, and Consciousness are common to everybody. Regarding the last three psychical elements, thought animals do not and cannot function so well as man, nevertheless, they are sensitive to pain and pleasure all the same. Moreover, craving for live and fear of death are natural instincts of all animals. Thus, Buddha says: "Because Buddha-nature is inherent in all sentient beings, they are at parity with each other." However, people generally separate themselves from others, by making distinctions between Ego-personality and Other-personality. Furthermore, they pay so much attention to the Five-Aggregates-constituted body that it leads them to egoism, craving, stupidity and arrogance. Consequently, they come into conflict with others and resort to every means to overcome them. After all, if they realize this fundamental Buddhist Principle of Universal Equality, they can see that Ego-personalty is unreal and illusory, and the so-called "enemy" is also illusory. An Enlightened being can easily see that the whole thing is but an illusion.

The Sutra says: "All causally produced phenomena, I say, are empty and unreal, and their names are also fictitious. This is the Middle-Way Doctrine." Inasmuch as the "I-personality" constituted by the five Aggregates, is casually produced, it can be seen that neither from those psychical aspects of sensation, conception, volition and consciousness, nor from the material aspects of the body, such as bone, blood, flesh, etc. and still less, from atoms, can it be found. Positively, the phenomenon of "I-personality" is empty and unreal; for conventional usage, however, it is called the "I-personality". At any rate, if we are free from stupidity, arrogance, conceit and craving, not only we would regard all sentient beings to be of one entity with us, but also would extend every help to them, thus we may be said to be carrying out the Middle Doctrine in practical way. Moreover, apart from the "I-personality", the phenomena of all things are also produced by causes and conditions, hence, they are devoid of self-nature; inversely speaking, had they had self-nature, they would not have been dependent upon causes and conditions. This holds true not only with all material things but also with all Terms, all Theorems and all "…ISMs." For instance, if a country, which is constituted of land, people and sovereignty, lacks any of these elements, it is no longer a country, because of its being dependent on the combination of elements, it is devoid of self-nature, and because it is an illusory phenomenon, it is said to be empty and unreal. Likewise, an army, made up of a multitude of people in uniform and with military training, is also devoid of self-nature; for without uniform, military training, and people, no army can be formed. In the light of this understanding we would perceive the reality of everything without being deceived by its illusory phenomenon and also we would be free from misconceptions and discriminations. Again, on the question of mental phenomena, all principles and theories are nothing but a group of names, where nothing real can be found. Therefore, those who fail to see that both the ego-personality and things are empty and illusory, are really "pitiable and ignorant" of Truths of life.

"From what you have said" someone may argue to say, "Buddhism, as a Dharma, is also devoid of self-nature, thus it is empty and unreal, isn’t it?" I would reply: " Yes, it is. You are absolutely correct and this is right understanding of Buddhism." The Diamond Sutra says in the same vein: "What is called Buddhism is not Buddhism." Also it says: "If someone says that the Tathagata expounds the Dharma, he is slandering the Buddha, for he does not understand what I say at all. Subhuti, one who expounds Buddhism has no Dharma to expound, and thus he may be said to expound Buddhism." In view of the fact that owing to their ignorance, sentient beings are subjected to numerous defilements and heterodox views, Buddha therefore expounds Buddhism in various ways to cure them of their specific ills and to help them realize self-enlightenment according to their cultivation of awareness. In short, Buddhism is established on the basis of sentient beings’ stupidity, and if their stupidity is removed, there would be no (need of) Buddhism at all.

(B) The True Meaning of Objectivity

Objectivity is generally held to be a scientific way of looking into a problem or thing. From the standpoint of Buddhism, we should understand this popular term clearly, or we would miss its important sense entirely. If there is an object to be viewed, there must be a subject capable of viewing it, and whatever the view may be, it is always subjective and cannot be objective at all. As to the object, it may be a living being or a non-being; if it is a non-living being, logically it cannot view itself objectively at all, and if a living being, then it would turn into a subject and what is viewed would be subjective. From this, it may be said that the conventional conception of objectivity is vague and confusing. By the conventional standard, the so-called objectivity implies the following three characteristics: 1) unmixed with sentiments; 2) in accord with generally accepted truth; 3) based on logical reasoning. If these requisites can be fully met, objectivity is right there. This, as viewed by Buddhism, however, is not absolute objectivity at all. The fundamental truth is this: all dharmas are essentially pure and equal with one another. However, holding the misconception that the "I-personality" is real and permanent, sentient beings make distinctions and barriers between themselves and other people, they become increasingly egoistic. Consequently, whatever they like, they accept, and whatever they dislike, they reject. Such is the general way of life with all sentient beings of the world. Consequently, antagonism and conflict of interests is their order of the day; hence, what is fundamentally pure becomes defiled at once, and what is fundamentally universal equality, is no longer practised. This may be illustrated with a metaphor. If stones are thrown into a clear and smooth pool, the water will be turbulent with numerous bubbles; extending its way from its center to the outside, each bubble comes into collision with other adjourning ones, thus the water of the pool is all commotion at once. The subjective mind of every sentient being, like each bubble, acts identically the same, and also with the same effect. From this metaphor, it may be inferred that with regard to everything and every phenomenon, sentient beings are bound to think of them subjectively, and moreover, even the so-called objective phenomena and objective principles are not uncommonly interwoven with a good deal of subjective thinking, and are not devoid of the motive of self-interest. With scientific measurement instruments and mathematical formulae, this also holds true. In order that truth may be absolutely and truly objective, it is necessary that ego-personality be completely eradicated, with neither a subject nor an object to be involved. In this way, the mind is calm like still water, and bright like a clear mirror, and whatever it reflects, is nothing but the true image. This is true objectivity.

(C) Compassion and Altruism

Whereas altruism is strongly advocated by religious people with hearty support of many scholars, and its high principle is held to be irrefutable and incontrovertible truth, Buddhism, however, says nothing of altruism, but on the contrary, urges that love, as the root cause of all sufferings and samsaric existence(existence of samsara), by all means, should be discarded. What is the difference between compassion and altruism? According to Buddhism, positively there is a world of difference between the two. Where there is love, it involves two aspects of love a subject to love and an object to be loved, e.g. the "I-personality" and the other or others, and between the two, there is a marked difference of love. Usually, one loves oneself more than others. If someone say that he loves others more than himself, it may be conceded that in such case, the motive of prejudice is not ruled out. Moreover, if love is conditional, and, as conditions are not immutable, change of love or loss of love would be inevitable, e.g. one may love another person because of the latter’s appearance, education, character, etc. but since all these things are subjected to change and if they are changed for worse, then love would be quickly lost. Again, assuming that the object of love is a person, and there is a rivalry of love over the same person, in such case, whoever captures the object, envy and conflict would remain unabated; thus there would be the suffering of meeting the hated, the suffering of not getting what one craves for, the suffering of parting with the beloved, and under these conditions, the pure and peaceful world would be turned into "five turbulent worlds." In view of this, Buddha says that love is the root cause of transmigration and the source of vexations and sorrow. Considering that love is the cause of defilement, no matter how broadly, extensively and infinitely it may be extended to others, one can not be free from its power of contamination. An this is the reason why Buddhism refrains from promoting altruism. "Love thy enemies", another popular slogan on the lips of faithful religious people, is paradoxical, if not hypocritical, for as long as there is "the enemy" in the sayer’s mind, there is no abatement of such bitter feelings as envy, hate and vengeance, therefore to say of loving one’s enemy is utterly a hypocrisy, lying and deception. On the other hand, Buddhism teaches us that the way to deal with those of evil intent is to look upon them neither as enemy nor as friend, but in accord with the fundamental principle of universal equality, to treat them as equals, and in playing this game, there is no place for love, because, on the understanding that all sentient beings are of one entity, and, therefore at parity with one another, at once All-Compassion would be aroused, averting every evil intention, and so nothing but happy feeling would ensue. In the light of this principle of Buddhism, let us proceed further to understand the true meaning of compassion.

In Buddhism, Compassion is defined with two Chinese characters "Chi", "Bei"; "Chi" means loving-kindness to help others joyfully, and "Bei" means to deliver others from suffering out of pity. These two aspects of compassion are selfless, non-egoistic and based on the principle of universal equality. Here at this point lies the fundamental difference between compassion and altruism. As mentioned previously, as far as the material elements of the body and the psychical aspect of consciousness are concerned, all sentient beings are identical with one another. This shows conclusively that they are of one entity and at parity with one another. Hence, in Buddhist terms, "Chi" is said to be "pity for one and same entity". Therefore in practising Compassion-Meditation, one should dwell with full attention on the thought that since all sentient beings, oneself included are of one substance and at parity with one another, one should help them, as best as one can, to satisfy their needs: If giving charity, he does not cherish the thought that he is the giver, and sentient beings are the receivers, what is given and how much is given, thus, in one’s mind no arrogance and self-conceit would arise; if charity is given without expecting fame, remuneration or anything in return and without any conditions whatsoever, this is called : "unconditioned almsgiving" or "compassion on equality basis". If this principle of affinity of substance and equality of all sentient beings is put into practice, one would look upon others’ sufferings as if one’s own, and compassion would be aroused spontaneously and indiscriminately. And if help is given without making distinctions of "self" and others, without consideration of personal gains or advantages, and without any ulterior motive, this is called "The Great All-Compassion for the same entity".

In the light of the principle of compassion, at once we can realize that it is wrong to kill those living things for food to satisfy our appetites; it is wrong to take what is not our own for personal enjoyment; it is wrong to have improper sexual relations. We can realize that passionate desire for beauty and wealth is nothing but manifestation of the mind, where both the subject and the object of desire are empty and unreal; from this standpoint, all killing, stealing and debauchery committed by sentient beings cannot but be called "stupidity".

Again, with our understanding of the principle of compassion, we can realize that it is foolish to say of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara’s remarkable miracles as superstition, inasmuch as both Dharmakaya of every Bodhisattva and the essence of sentient beings are of one substance and at parity with each other, and it is because of this affinity that the S.O.S. call of the one may draw the spontaneous compassionate response of the other; however, there must be no lack of sincerity, otherwise the mid of sentient beings, contaminated by cravings and defilements, would hardly be in unison with that of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, and if the two minds do not meet on the common ground, it means that sentient beings are separating themselves far apart from the Bodhisattva and the two are not of one and the same essence, in that event when there is no compassion on the part of the sentient beings, naturally there will be no response from the compassionate Bodhisattva, for only the like may draw the like together; in short, without evoking compassion, one can hardly accomplish anything, and even the Dharma of Reciting Buddha can be of little avail.

(D) Distinguishing The Good and The Evil

"Refrain from every evil. Practise every good deed." So popular is this dictum that even a little child may be able to say it. In view of the fact that it is generally accepted by every religion, some simple-minded people assume that because all religions teach morality, they are all beneficial to humanity. To scientific-minded person who go into every question by analytic and deductive reasoning, such assumption sounds too simple to be true. Here are a few relevant questions: 1) How do these religions of the world define right and wrong in their own way? 2) What are the criteria to distinguish the right and wrong? 3) What is the objective of every religion to urge people to do good and not to do evil? 1)) Regarding the first question of defining right and wrong, not only there is no uniformity among the world religions; in some respects, they are at variance with one another; whiles ancestral worship is disapproved by some religions, it is supported by Buddhism and Confucianism; again, according to some religions, there is nothing wrong with killing animals for food as they are made by the Creator for human consumption; another religion forbids eating a certain kind of animal only. According to Buddhism, positively it is wrong to kill animals, birds, fish and any other living things just to satisfy one’s palate for food. 2)) As to the question of criteria to determine right and wrong, again, there is no uniformity among the world religions, as every religion goes by its own laws established by its founder, and to disobey them is considered sinful; on the other hand, Buddhism sets up most meticulous rules of discipline for Buddhist at different levels of spiritual development. Those rules for monks and nuns are more numerous and more strict than those for lay Buddhists at large, and what is permissible for Bhiskshus and Bhikshunis does not apply to Buddhists ordained for Bodhisattvahood. 3)) On the question of the objective of moral teaching, all religions hold different views from one another; to go to Paradise is the goal of some religion and to be saints and sages is the aspiration of another, but Buddhism asks for no reward whatsoever either from this world or from Buddha-lands for what Buddhists may attain spontaneously at the advanced stage of buddhahood development is Supreme Perfect Enlightenment. After all, it must be conceded that the question of right and wrong is not so simple as ordinary people think it to be.

Indeed, Buddhism treats the principle of right and wrong most meticulously and most comprehensively. One may do good deeds in either positive or negative way, and good deeds may be either producing good karma or entirely free from karma. If one practises good deeds actively and energetically, this is said to be working in the positive way, and if one refrains from doing evils, this is said to be doing good in the negative way; good deeds that are productive of good karma are not all free from defilements and may be subject to further changes, but good deeds that are karma-free are undefiled pure and unconditioned. Being unable to discern clearly what is right and what is wrong, people generally would say: "I’ll do what is right as prompted by my clear conscience. In my life I’ve never done any evil." This, however, is no assurance at all that one may not go wrong, in view of the fact that every day, every minute, one may be subjected to the impact of stupidity, egoism, arrogance, craving, etc in every act of his daily life, and so he is sowing numerous seeds of bad karma continually and incessantly. Moreover, the so-called "conscience" is no other than the six discriminating Consciousnesses, which, as described in the Sutra, are the "six thieves in one’s own house". This is how unconsciously, one goes wrong easily from day to day, or from moment to moment. In order to do the good and not the evil, the first and foremost thing is to realize the true meaning of good and evil before one chooses what to do, and in order to discern the good and the evil correctly, it is necessary to have good understanding of the fundamental truth of Equality. From the standpoint of Buddhism, true Equality is where the sentient beings art at parity with one another, where there is neither a subject nor an object of parity, nor any distinction between Ego-personality and other-personality. In delusion, sentient beings, however, make discrimination of subject and object, the ego and others; from egoism arise arrogance, pride and self-conceit, and for themselves, they would grab everything, by hook or by crook. This is the fundamental reason why the Ten Demeritorious Deeds (greed, hatred, stupidity, killing, stealing, debauchery, gossip, slander, lying, frivolous talk) and erroneous views crop up in the world so abundantly. IN short, as long as there is egoism, regardless whatever one may do for oneself or for others, all thoughts and behavior corresponding to it would be bad karma automatically; on the other hand, if one is free of egoism, invariable every deed would be good karma. All this shows that in defining and distinguishing right and wrong, Buddhism tackles the question fundamentally at its very root. However, in view of the numerous bad karma of sentient beings accumulated from beginningless time, Buddha has set up various expedient means of cultivation to help all of them at different levels of development to attain gradually the goal of self-enlightenment. On the other hand, other religions, ignorant of the fundamental truth of universal equality of all sentient beings, not only look upon killing living creatures with immunity but also with approval on the ground that though animals have life, they have no consciousness at all and furthermore, they are made by the Creator for human food; positively such heretical views are in striking contrast with the Buddhist principle of Universal Equality of sentient beings. Whereas monotheistic and polytheistic religions, by the imposition of reward and punishment, ask people to believe in God or gods, e.g. believers would go to Paradise and non-believers to hell, Buddhism says that because Buddha-nature is immanent in everyone, fundamentally Buddha and sentient beings are at parity with each other. From this standpoint of Buddhism, to believe in God or any deity to be higher than sentient beings runs counter to the Principle of Universal Equality.

As to the question of establishing criteria to determine right and wrong, instead of stressing on the act, as conventional practices usually do, Buddhism probes into the motive of the act. In the view of Buddhism, scolding and hitting others may not be a bad thing at all if it is done for their benefit, and paying compliments and respects to others may be insincere and wrongful if it is done for an ulterior motive; for one practising Bodhisattva discipline rules, it may not be wrong to kill or to steal, provided that this is done entirely for others’ benefit. To illustrate, if an avaricious and chauvinistic despot, who has caused the loss of innumerable lives and properties of his people, is killed by a Buddhist undergoing Bodhisattva discipline, this is considered not only justifiable and noble, but also highly meritorious. In view of this, we can see what a Positive and Rational religion Buddhism is.

Chapter 4

Distinguishing The Good and The Evil

"Refrain from every evil. Practise every good deed." So popular is this dictum that even a little child may be able to say it. In view of the fact that it is generally accepted by every religion, some simple-minded people assume that because all religions teach morality, they are all beneficial to humanity. To scientific-minded person who go into every question by analytic and deductive reasoning, such assumption sounds too simple to be true. Here are a few relevant questions: 1) How do these religions of the world define right and wrong in their own way? 2) What are the criteria to distinguish the right and wrong? 3) What is the objective of every religion to urge people to do good and not to do evil? 1)) Regarding the first question of defining right and wrong, not only there is no uniformity among the world religions; in some respects, they are at variance with one another; whiles ancestral worship is disapproved by some religions, it is supported by Buddhism and Confucianism; again, according to some religions, there is nothing wrong with killing animals for food as they are made by the Creator for human consumption; another religion forbids eating a certain kind of animal only. According to Buddhism, positively it is wrong to kill animals, birds, fish and any other living things just to satisfy one’s palate for food. 2)) As to the question of criteria to determine right and wrong, again, there is no uniformity among the world religions, as every religion goes by its own laws established by its founder, and to disobey them is considered sinful; on the other hand, Buddhism sets up most meticulous rules of discipline for Buddhist at different levels of spiritual development. Those rules for monks and nuns are more numerous and more strict than those for lay Buddhists at large, and what is permissible for Bhiskshus and Bhikshunis does not apply to Buddhists ordained for Bodhisattvahood. 3)) On the question of the objective of moral teaching, all religions hold different views from one another; to go to Paradise is the goal of some religion and to be saints and sages is the aspiration of another, but Buddhism asks for no reward whatsoever either from this world or from Buddha-lands for what Buddhists may attain spontaneously at the advanced stage of buddhahood development is Supreme Perfect Enlightenment. After all, it must be conceded that the question of right and wrong is not so simple as ordinary people think it to be.

Indeed, Buddhism treats the principle of right and wrong most meticulously and most comprehensively. One may do good deeds in either positive or negative way, and good deeds may be either producing good karma or entirely free from karma. If one practises good deeds actively and energetically, this is said to be working in the positive way, and if one refrains from doing evils, this is said to be doing good in the negative way; good deeds that are productive of good karma are not all free from defilements and may be subject to further changes, but good deeds that are karma-free are undefiled pure and unconditioned. Being unable to discern clearly what is right and what is wrong, people generally would say: "I’ll do what is right as prompted by my clear conscience. In my life I’ve never done any evil." This, however, is no assurance at all that one may not go wrong, in view of the fact that every day, every minute, one may be subjected to the impact of stupidity, egoism, arrogance, craving, etc in every act of his daily life, and so he is sowing numerous seeds of bad karma continually and incessantly. Moreover, the so-called "conscience" is no other than the six discriminating Consciousnesses, which, as described in the Sutra, are the "six thieves in one’s own house". This is how unconsciously, one goes wrong easily from day to day, or from moment to moment. In order to do the good and not the evil, the first and foremost thing is to realize the true meaning of good and evil before one chooses what to do, and in order to discern the good and the evil correctly, it is necessary to have good understanding of the fundamental truth of Equality. From the standpoint of Buddhism, true Equality is where the sentient beings art at parity with one another, where there is neither a subject nor an object of parity, nor any distinction between Ego-personality and other-personality. In delusion, sentient beings, however, make discrimination of subject and object, the ego and others; from egoism arise arrogance, pride and self-conceit, and for themselves, they would grab everything, by hook or by crook. This is the fundamental reason why the Ten Demeritorious Deeds (greed, hatred, stupidity, killing, stealing, debauchery, gossip, slander, lying, frivolous talk) and erroneous views crop up in the world so abundantly. IN short, as long as there is egoism, regardless whatever one may do for oneself or for others, all thoughts and behavior corresponding to it would be bad karma automatically; on the other hand, if one is free of egoism, invariable every deed would be good karma. All this shows that in defining and distinguishing right and wrong, Buddhism tackles the question fundamentally at its very root. However, in view of the numerous bad karma of sentient beings accumulated from beginningless time, Buddha has set up various expedient means of cultivation to help all of them at different levels of development to attain gradually the goal of self-enlightenment. On the other hand, other religions, ignorant of the fundamental truth of universal equality of all sentient beings, not only look upon killing living creatures with immunity but also with approval on the ground that though animals have life, they have no consciousness at all and furthermore, they are made by the Creator for human food; positively such heretical views are in striking contrast with the Buddhist principle of Universal Equality of sentient beings. Whereas monotheistic and polytheistic religions, by the imposition of reward and punishment, ask people to believe in God or gods, e.g. believers would go to Paradise and non-believers to hell, Buddhism says that because Buddha-nature is immanent in everyone, fundamentally Buddha and sentient beings are at parity with each other. From this standpoint of Buddhism, to believe in God or any deity to be higher than sentient beings runs counter to the Principle of Universal Equality.

As to the question of establishing criteria to determine right and wrong, instead of stressing on the act, as conventional practices usually do, Buddhism probes into the motive of the act. In the view of Buddhism, scolding and hitting others may not be a bad thing at all if it is done for their benefit, and paying compliments and respects to others may be insincere and wrongful if it is done for an ulterior motive; for one practising Bodhisattva discipline rules, it may not be wrong to kill or to steal, provided that this is done entirely for others’ benefit. To illustrate, if an avaricious and chauvinistic despot, who has caused the loss of innumerable lives and properties of his people, is killed by a Buddhist undergoing Bodhisattva discipline, this is considered not only justifiable and noble, but also highly meritorious. In view of this, we can see what a Positive and Rational religion Buddhism is.

(B) The Universal Law of Cause and Effect

In all aspects of transformations of A) matter, B) mind, and C) matter and mind combined, the Law of Cause and Effect extends its operation incessantly and continuously. From the time of their spiritual development to their attainment of Buddhahood, in and out of this world, sentient being are subjected to the operation of this Law. In view of its extensive application, it may be fittingly called The Universal Law of Cause and Effect. For short, it is called the Law of Cause and Effect; for elaboration, "Cause and Conditions, Fruit and Retribution." The cause means the primary cause and conditions are auxiliary causes; whatever is produced by cause and conditions is called "fruit", and to whoever is responsible for making the cause, the fruit is identically a "retribution". The Law of Cause, Condition, Fruit and Retribution is well summed up in the following gatha: "Even with the passing of hundreds and thousands of aeons, one’s karma may remain and would not bear the fruit till the cause and conditions meet, and then none but its maker alone would have to bear the suffering of the retribution. "In the gatha three points are noteworthy: 1) Karma, as a cause, would not be nullified by itself even after the lapse of long, long time, same as what was said in Newton’s Law of Motion that still things always remained still and moving things were always on the move, and in either case, they would not by themselves, change their phenomena of stillness and motion, unless intervened by an external force. 2) When the cause and conditions meet together, regardless how long and how short this may take, the fruit would be produced eventually, e.g. by the external force, still things would move at once and moving things would either change their direction, or accelerate their speed or come to stop. 3) By one’s doing, which is the cause, one gets the fruit automatically, this is to say, for one’s happiness or misery, one oneself alone is responsible, and neither happiness is reward, nor misery is punishment from God; as claimed by some religion, one gets retribution for another’s doing, and vice versa, but such cases are repudiated by Buddhism to be fallacious and illogical. In science, the Law of Cause and Effect, though included in the Universal Law of Cause and Effect, deals only with material things and their interrelationships. But if the object of research has to do with human affairs or with the mind, then the scientific experiment would come to a halt. From this, it may be seen that the cause-and-effect relationships expounded by science are comparatively simple. For example, when a copper wire moves in a magnetic field, in order to intercept the magnetic line of force, electric pressure would be produced. In this case, the copper wire is the primary cause, its motion and the magnetic line are the conditions and the electric pressure is the effect; but it there is no copper wire, or if the wire is not moving in the magnetic field to counteract the magnetic line of force, there would be no electric pressure at all. From this, it can be clearly seen that the cause-and-effect relationships of material things may be summed up in a simple dictum: "such cause, such effect". In a word, the Law of Cause and Effect works out automatically and precisely in due time. Not only it applies to relationships between the material things, but also those between mind and mind, and to those of combined matter and mind as well. Considering that matter and mind are of one integrated whole, it can be inferred that the Law of Causality, that applies to the one, also holds good with the other.

Of couse, the interrelationships of combined matter and mind are far more complicated than those of material things discussed in the foregoing, and what is said on this question so far, is too precise, readers may better refer to Buddhist Scriptures for comprehensive and meticulous details. Speaking of causes, there are tow fundamental theories: 1) the six causes given by Abbhidharma-kosa-Sastra; and 2) the ten causes given by Yogacarabhumi-Sastra; in both Sastras the sphere of causes is so extensive that conditions (secondary causes) are also included. In Dirghagama Sutra conditions are classified into four different kinds: a) Primary cause and Secondary cause, b) Equal Incessant Causes, c) Condition qua perceived qua perceived object, and d) Condition qua contributing factor (causes helping primary cause to grow). This classification of cause and conditions is common to both Mahayana and Hinayana Schools. In the Pali texts there are as many as twenty-four conditions, resulting from the further divisions of both Condition qua perceived object and Condition qua contributing factor. Under those twenty-four conditions all aspects of interrelationships between mind and form, mind and mind, mind and combined matter and mind, body and mind, combined body and mind and another combined body and mind are dealt with at great length. From this, we can see that the question of complicated and comprehensive relationships of those diverse and manifold phenomena of the world is dealt with thoroughly and scientifically in Buddhism. Let us take up those four general Conditions for brief discussion.

1) Both cause and conditions are primary causes. For instance cotton is the primary cause of yarn, wheat, the cause of flour, and copper wire, the cause of electric current. As to those cases where mind is concerned or where matter and mind are involved, every act of the body, of the mouth, of the mind, commonly called karma, is the primary cause.

2) By Equal Incessant Cause, it is meant that owing to the eight Consciousness and their Mental Associates, thoughts arise and pass out from moment to moment continually in succession, and when transformation is brought about in this manner, the cause is called Equal Incessant Cause. Such cause applies to phenomena of the mind exclusively.

3) When the discriminating mind and the objects of discrimination are confronting each other, with the former looking upon the latter as the object of causation, such phenomenon is attributed to be the secondary cause responsible for subsequent thoughts; thus it is called Condition qua perceived objects.

4) In all psychic and material phenomena, those causes, either by their being in accord with, or by their being in opposition to the primary cause, affects its subsequent development, and for this reason, they are called Conditions que contributing factor. It holds only with phenomena of material things that if there are a primary cause and conditions qua perceived objects, the fruit would be produced accordingly, but as to those phenomena where mind is involved, the four conditions must be present together to bear the fruit.

Fruits produced by the combination of causes and conditions as enumerated in the foregoing are classified in to five categories:

1) Vipakaphala, (retribution maturing at various times);

2) Nisyandaphala, (like effects from like causes);

3) Visamyogaphala (cutting off the retribution bond);

4) Perusakaraphala, (the fruit as result of human activity);

5) Adhiputiphala, (dominant effect or superior fruit).

For better and deeper understanding of those interrelationships, readers may refer to Abhidharma-kosa-Sastra and Vidya-matra-siddhi Sastra(Theory of Mere Consciousness).