Difference between revisions of "C. George Boeree: An Introduction to Buddhism"

(Created page with " <poem> C. George Boeree: ages of this web site were written for the students of my class on Buddhist Psychology. Although the religious aspects of Buddhism are d...") |

|||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{DisplayImages|594|109|1079|1391|944|1903|1648|674|265|1860|687|1121|1099|1496|1895|11|1919|1968|811|1423|79|920|1027|1564|242|582|451|1671|281|2114|1890|1946|651|1802|1641|1588|82|18|1542|163|1460|1913|1594|151|1536|358|115|1069|1006|1002|555|1400|2058|1436|1381|1589|2124|858|667|1269|1920|2017|99|66|1153|672|1817|1953|369|376|1303|338|255|1635|49|1312|741|364|39|1409|1447|733|1417|498|1831|1195|101|139|660|492|1510|317|774|1243|1406|2003|227|51|9|62}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 24: | ||

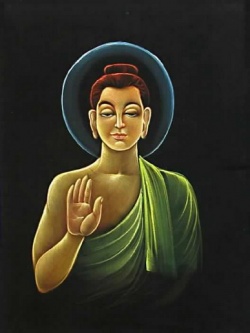

The [[Buddha]] was born [[Siddhartha Gautama]], a {{Wiki|prince}} of the [[Sakya tribe]] of [[Nepal]], in approximately 566 BC. When he was twentynine years old, he left the | The [[Buddha]] was born [[Siddhartha Gautama]], a {{Wiki|prince}} of the [[Sakya tribe]] of [[Nepal]], in approximately 566 BC. When he was twentynine years old, he left the | ||

| − | comforts of his home to seek the meaning of the [[suffering]] he saw around him. After six years of arduous [[yogic]] training, he abandoned the way of selfmortification and instead sat in [[mindful]] [[meditation]] | + | comforts of his home to seek the meaning of the [[suffering]] he saw around him. After six years of arduous [[yogic]] {{Wiki|training}}, he abandoned the way of selfmortification and instead sat in [[mindful]] [[meditation]] |

beneath a [[bodhi tree]]. | beneath a [[bodhi tree]]. | ||

| − | On the [[full moon]] of May, with the rising of the morning star, [[Siddhartha Gautama]] became the | + | On the [[full moon]] of May, with the [[rising]] of the morning {{Wiki|star}}, [[Siddhartha Gautama]] became the |

[[Buddha]], the [[enlightened one]]. | [[Buddha]], the [[enlightened one]]. | ||

| − | The [[Buddha]] wandered the plains of northeastern [[India]] for 45 years more, [[teaching]] the [[path]] or [[Dharma]] he had [[realized]] in that moment. Around him developed a {{Wiki|community}} or [[Sangha]] of [[monks]] and, later, [[nuns]], | + | The [[Buddha]] wandered the plains of northeastern [[India]] for 45 years more, [[teaching]] the [[path]] or [[Dharma]] he had [[realized]] in that [[moment]]. Around him developed a {{Wiki|community}} or [[Sangha]] of [[monks]] and, later, [[nuns]], |

drawn from every tribe and [[caste]], devoted to | drawn from every tribe and [[caste]], devoted to | ||

practicing this [[path]]. In approximately 486 BC, at the age of 80, the [[Buddha]] [[died]]. His last words are said to be... | practicing this [[path]]. In approximately 486 BC, at the age of 80, the [[Buddha]] [[died]]. His last words are said to be... | ||

| Line 24: | Line 34: | ||

Strive on with [[awareness]]. | Strive on with [[awareness]]. | ||

| − | Including the | + | [[Including]] the [[Mahamangala Sutta]] |

An Introduction to [[Buddhism]] 5 | 86 The [[Life]] of [[Siddhartha Gautama]] | An Introduction to [[Buddhism]] 5 | 86 The [[Life]] of [[Siddhartha Gautama]] | ||

| − | There was a small country in what is now southern [[Nepal]] that was ruled by a {{Wiki|clan}} called the [[Shakyas]]. The head of this {{Wiki|clan}}, and the [[king]] of this country, was named | + | There was a small country in what is now southern [[Nepal]] that was ruled by a {{Wiki|clan}} called the [[Shakyas]]. The head of this {{Wiki|clan}}, and the [[king]] of this country, was named [[Shuddodana Gautama]], and his wife was the beautiful [[Mahamaya]]. [[Mahamaya]] was expecting her first born. She had had a strange [[dream]] in which a baby [[elephant]] had blessed her with his trunk, which was understood to be a very [[auspicious]] sign to say the least. As was the {{Wiki|custom}} of the day, when the [[time]] came near for [[Queen Mahamaya]] to have her child, she traveled to her father's {{Wiki|kingdom}} for the [[birth]]. |

| + | |||

| + | But during the long journey, her [[birth]] [[pains]] began. In the small town of [[Lumbini]], she asked her handmaidens to assist her to a nearby grove of [[trees]] for privacy. One large [[tree]] lowered a branch to her to serve as a support for her delivery. They say the [[birth]] was nearly painless, even though the child had to be delivered from her side. After, a gentle [[rain]] fell on the mother and the child to cleanse them. | ||

| − | It is said that the child was born fully awake. He could speak, and told his mother he had come to free all mankind from [[suffering]]. He could stand, and he walked a short distance in each of the four [[directions]]. [[Lotus]] blossoms rose in his footsteps. They named him [[Siddhartha]], which means "he who has attained his goals." Sadly, [[Mahamaya]] [[died]] only seven days after the [[birth]]. After that [[Siddhartha]] was raised by his mother’s kind sister, [[Mahaprajapati]]. [[King]] Shuddodana consulted [[Asita]], a well-known sooth-sayer, concerning the {{Wiki|future}} of his son. [[Asita]] proclaimed that he would be one of two things: He could become a great [[king]], even an [[emperor | + | It is said that the child was born fully awake. He could speak, and told his mother he had come to free all mankind from [[suffering]]. He could stand, and he walked a short distance in each of the four [[directions]]. [[Lotus]] blossoms rose in his footsteps. They named him [[Siddhartha]], which means "he who has [[attained]] his goals." Sadly, [[Mahamaya]] [[died]] only seven days after the [[birth]]. After that [[Siddhartha]] was raised by his mother’s kind sister, [[Mahaprajapati]]. [[King]] [[Shuddodana]] consulted [[Asita]], a well-known sooth-sayer, concerning the {{Wiki|future}} of his son. [[Asita]] proclaimed that he would be one of two things: He could become a great [[king]], even an [[emperor]]. |

| − | [[ | + | Or he could become a great [[Wikipedia:Sage (sophos|sage]] and savior of [[humanity]]. The [[king]], eager that his son should become a [[king]] like himself, was determined to shield the child from anything that might result in him [[taking up]] the [[religious]] [[life]]. And so [[Siddhartha]] was kept in one or another of their three {{Wiki|palaces}}, and was prevented from experiencing much of what [[ordinary folk]] might consider quite commonplace. He was not permitted to see the elderly, the sickly, the [[dead]], or anyone who had dedicated themselves to [[spiritual]] practices. Only [[beauty]] and [[health]] surrounded [[Siddhartha]]. |

| − | + | [[Siddhartha]] grew up to be a strong and handsome young man. As a {{Wiki|prince}} of the [[warrior]] [[caste]], he trained in the [[arts]] of [[war]]. When it came [[time]] for him to marry, he won the hand of a beautiful {{Wiki|princess}} of a neighboring {{Wiki|kingdom}} by besting all competitors at a variety of [[sports]]. [[Yashodhara]] was her [[name]], and they [[married]] when both were 16 years old. | |

| − | + | As [[Siddhartha]] continued living in the {{Wiki|luxury}} of his {{Wiki|palaces}}, he grew increasing restless and curious about the [[world]] beyond the palace walls. He finally demanded that he be permitted to see his [[people]] and his lands. The [[king]] carefully arranged that [[Siddhartha]] should still not see the kind of [[suffering]] that he feared would lead him to a [[religious]] [[life]], and decried that only young and healthy [[people]] should greet the {{Wiki|prince}}. As he was lead through [[Kapilavatthu]], the capital, he chanced to see a couple of old men who had accidentally wandered near the parade route. Amazed and confused, he chased after them to find out what they were. Then he came across some [[people]] who were severely ill. | |

| − | + | And finally, he came across a [[funeral]] {{Wiki|ceremony}} by the side of a [[river]], and for the first [[time]] in his [[life]] saw [[death]]. He asked his [[friend]] and squire [[Chandaka]] the meaning of all these things, and [[Chandaka]] informed him of the simple [[truths]] that [[Siddhartha]] should have known all along: That all of us get old, sick, and eventually [[die]]. [[Siddhartha]] also saw an [[ascetic]], a [[monk]] who had renounced all the [[pleasures]] of the flesh. The [[peaceful]] look on the [[monks]] face would stay with [[Siddhartha]] for a long [[time]] to come. Later, he would say this about that [[time]]: | |

| − | + | When [[ignorant]] [[people]] see someone who is old, they are disgusted and horrified, even though they too will be old some day. I [[thought]] to myself: I don’t want to be like the [[ignorant]] [[people]]. After that, I couldn’t [[feel]] the usual [[intoxication]] with youth anymore 86 When [[ignorant]] [[people]] see someone who is sick, they are disgusted and horrified, even though they too will be sick some day. I [[thought]] to myself: I don’t want to be like the [[ignorant]] [[people]]. After that, I couldn’t [[feel]] the usual [[intoxication]] with [[health]] anymore. | |

| − | + | When [[ignorant]] [[people]] see someone who is [[dead]], they are disgusted and horrified, even [[thought]] they too will be [[dead]] some day. I [[thought]] to myself: I don’t want to be like the [[ignorant]] [[people]]. After than, I couldn’t [[feel]] the usual [[intoxication]] with [[life]] anymore. (AN III.39, interpreted) At the age of 29, [[Siddhartha]] came to realize that he could not be [[happy]] living as he had been. He had discovered [[suffering]], and wanted more than anything to discover how one might overcome [[suffering]]. | |

| − | [[Siddhartha]], now the [[Buddha]], remained seated under the [[tree]] – which we call the [[bodhi tree]] – for many days longer. It seemed to him that this [[knowledge]] he had gained was far too difficult to {{Wiki|communicate}} to others. Legend has it that [[Brahma]], [[king of the gods]], convinced [[Buddha]] to teach, saying that some of us perhaps have only a little dirt in our [[eyes]] and could [[awaken]] if we only heard his story. [[Buddha]] agreed to teach. At [[Sarnath]] near [[Benares]], about one hundred {{Wiki|miles}} from [[Bodh Gaya]], he came across the [[five ascetics]] he had practiced with for so long. There, in a [[deer park]], he {{Wiki|preached}} his first {{Wiki|sermon}}, which is called "setting the [[wheel]] of the [[teaching]] in motion." He explained to them the [[Four Noble Truths]] and the [[Eightfold Path]]. They became his very first [[disciples]] and the beginnings of the [[Sangha]] or [[community of monks]]. | + | After kissing his [[sleeping]] wife and newborn [[son Rahula]] goodbye, he snuck out of the palace with his squire [[Chandara]] and his favorite [[horse]] [[Kanthaka]]. He gave away his rich clothing, cut his long [[hair]], and gave the [[horse]] to [[Chandara]] and told him to return to the palace. He studied for a while with two famous [[gurus]] of the day, but found their practices lacking. |

| + | |||

| + | He then began to practice the austerities and self-mortifications practiced by a group of [[five ascetics]]. For six years, he practiced. The sincerity and intensity of his practice were so astounding that, before long, the [[five ascetics]] became followers of [[Siddhartha]]. But the answers to his questions were not forthcoming. He redoubled his efforts, refusing [[food]] and [[water]], until he was in a [[state]] of near [[death]]. One day, a peasant girl named [[Sujata]] saw this starving [[monk]] and took [[pity]] on him. She begged him to eat some of her [[milk-rice]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Siddhartha]] then [[realized]] that these extreme practices were leading him nowhere, that in fact it might be better to find some [[middle way]] between the [[extremes]] of the [[life]] of {{Wiki|luxury}} and the [[life]] of selfmortification. So he ate, and drank, and bathed in the [[river]]. The [[five ascetics]] saw him and concluded that [[Siddhartha]] had given up the [[ascetic]] [[life]] and taken to the ways of the flesh, and left him. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the town of [[Bodh Gaya]], [[Siddhartha]] decided that he would sit under a certain fig [[tree]] as long as it would take for the answers to the problem of [[suffering]] to come. He sat there for many days, first in deep [[concentration]] to clear his [[mind]] of all {{Wiki|distractions}}, then in [[mindfulness]] [[meditation]], opening himself up to the [[truth]]. He began, they say, to recall all his previous [[lives]], and to see everything that was going on in the entire [[universe]]. On the [[full moon]] of May, with the [[rising]] of the morning {{Wiki|star}}, [[Siddhartha]] finally understood the answer to the question of [[suffering]] and became the [[Buddha]], which means "he who [[is awake]]." | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is said that [[Mara]], the [[evil one]], tried to prevent this great occurrence. He first tried to frighten [[Siddhartha]] with storms and armies of {{Wiki|demons}}. [[Siddhartha]] remained completely [[calm]]. Then he sent his three beautiful daughters to tempt him, again to no avail. Finally, he tried to ensnare [[Siddhartha]] in his [[own]] [[ego]] by appealing to his [[pride]]. That, too, failed. [[Siddhartha]], having conquered all temptations, touched the ground with one hand and asked the [[earth]] to be his {{Wiki|witness}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Siddhartha]], now the [[Buddha]], remained seated under the [[tree]] – which we call the [[bodhi tree]] – for many days longer. It seemed to him that this [[knowledge]] he had gained was far too difficult to {{Wiki|communicate}} to others. Legend has it that [[Brahma]], [[king of the gods]], convinced [[Buddha]] to teach, saying that some of us perhaps have only a little dirt in our [[eyes]] and could [[awaken]] if we only heard his story. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Buddha]] agreed to teach. At [[Sarnath]] near [[Benares]], about one hundred {{Wiki|miles}} from [[Bodh Gaya]], he came across the [[five ascetics]] he had practiced with for so long. There, in a [[deer park]], he {{Wiki|preached}} his first {{Wiki|sermon}}, which is called "setting the [[wheel]] of the [[teaching]] in {{Wiki|motion}}." He explained to them the [[Four Noble Truths]] and the [[Eightfold Path]]. They became his very first [[disciples]] and the beginnings of the [[Sangha]] or [[community of monks]]. | ||

| − | | 86 [[King Bimbisara]] of [[Magadha]], having heard [[Buddha’s]] words, granted him a [[monastery]] near Rahagriha, his capital, for use during the [[rainy season]]. This and other generous {{Wiki|donations}} permitted the {{Wiki|community}} of converts to continue their practice throughout the years, and gave many more [[people]] an opportunity to hear the teachings of the [[Buddha | + | | 86 [[King Bimbisara]] of [[Magadha]], having heard [[Buddha’s]] words, granted him a [[monastery]] near [[Rahagriha]], his capital, for use during the [[rainy season]]. This and other generous {{Wiki|donations}} permitted the {{Wiki|community}} of converts to continue their practice throughout the years, and gave many more [[people]] an opportunity to hear the teachings of the [[Buddha]]. |

| − | |||

| − | The [[Buddha]] said that it didn’t matter what a person’s {{Wiki|status}} in the [[world]] was, or what their background or [[wealth]] or nationality might be. All were capable of [[enlightenment]], and all were welcome into the [[Sangha]]. The first [[ordained]] [[Buddhist monk]], [[Upali]], had been a barber, yet he was ranked higher than [[monks]] who had been [[kings]], only because he had taken his [[vows]] earlier than they! [[Buddha’s]] [[life]] wasn’t without | + | Over [[time]], he was approached by members of his [[family]], [[including]] his wife, son, father, and aunt. His son became a [[monk]] and is particularly remembered in a [[sutra]] based on a [[conversation]] between father and son on the dangers of {{Wiki|lying}}. His father became a lay follower. Because he was saddened by the departures of his son and grandson into the [[monastic]] [[life]], he asked [[Buddha]] to make it a {{Wiki|rule}} that a man must have the permission of his [[parents]] to become a [[monk]]. [[Buddha]] obliged him. His aunt and wife asked to be permitted into the [[Sangha]], which was originally composed only of men. The {{Wiki|culture}} of the [[time]] ranked women far below men in importance, and at first it seemed that permitting women to enter the {{Wiki|community}} would weaken it. But the [[Buddha]] relented, and his aunt and wife became the first [[Buddhist]] [[nuns]]. |

| + | |||

| + | The [[Buddha]] said that it didn’t {{Wiki|matter}} what a person’s {{Wiki|status}} in the [[world]] was, or what their background or [[wealth]] or nationality might be. All were capable of [[enlightenment]], and all were welcome into the [[Sangha]]. The first [[ordained]] [[Buddhist monk]], [[Upali]], had been a barber, yet he was ranked higher than [[monks]] who had been [[kings]], only because he had taken his [[vows]] earlier than they! [[Buddha’s]] [[life]] wasn’t without | ||

disappointments. His cousin, [[Devadatta]], was an ambitious man. As a convert and [[monk]], he felt that he should have greater power in the [[Sangha]]. He managed to influence quite a few [[monks]] with a call to a return to extreme [[asceticism]]. Eventually, he conspired with a local [[king]] to have the [[Buddha]] killed and to take over the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}}. Of course, he failed. | disappointments. His cousin, [[Devadatta]], was an ambitious man. As a convert and [[monk]], he felt that he should have greater power in the [[Sangha]]. He managed to influence quite a few [[monks]] with a call to a return to extreme [[asceticism]]. Eventually, he conspired with a local [[king]] to have the [[Buddha]] killed and to take over the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}}. Of course, he failed. | ||

| − | [[Buddha]] had achieved his [[enlightenment]] at the age of 35. He would teach throughout [[northeast]] [[India]] for another 45 years. When the [[Buddha]] was 80 years old, he told his [[friend]] and cousin [[Ananda]] that he would be | + | [[Buddha]] had achieved his [[enlightenment]] at the age of 35. He would teach throughout [[northeast]] [[India]] for another 45 years. When the [[Buddha]] was 80 years old, he told his [[friend]] and cousin [[Ananda]] that he would be leaving them soon. And so it came to be that in [[Kushinagara]], not a hundred {{Wiki|miles}} from his homeland, he ate some spoiled [[food]] and became very ill. He went into a deep [[meditation]] under a grove of [[sala trees]] and [[died]]. His last words were... |

| − | leaving them soon. And so it came to be that in [[Kushinagara]], not a hundred {{Wiki|miles}} from his homeland, he ate some spoiled [[food]] and became very ill. He went into a deep [[meditation]] under a grove of [[sala trees]] and [[died]]. His last words were... | ||

[[Impermanent]] are all created things; | [[Impermanent]] are all created things; | ||

| Line 59: | Line 84: | ||

Resources: | Resources: | ||

| − | Snelling, John (1991). The [[Buddhist]] Handbook. Rochester, VT: Inner [[Traditions]]. The {{Wiki|Encyclopedia}} of Eastern [[Philosophy]] and [[Religion]] (1994). Boston: Shambhala. The Encyclopaedia Britannica CD (1998). {{Wiki|Chicago}}: Encyclopaedia Britannica | + | [[Snelling, John]]]] (1991). The [[Buddhist]] Handbook. Rochester, VT: Inner [[Traditions]]. The {{Wiki|Encyclopedia}} of Eastern [[Philosophy]] and [[Religion]] (1994). Boston: Shambhala. [[The Encyclopaedia Britannica]] CD (1998). {{Wiki|Chicago}}: [[Encyclopaedia Britannica]]. Soon after [[Buddha's]] [[death]] or [[parinirvana]], five hundred [[monks]] met at the [[first council]] at [[Rajagrha]], under the [[leadership]] of [[Kashyapa]]. |

| − | + | [[Upali]] recited the [[monastic code]] ([[Vinaya]]) as he remembered it. [[Ananda]], [[Buddha's]] cousin, [[friend]], and favorite [[disciple]] – and a man of [[prodigious]] [[memory]]! – recited [[Buddha's]] lessons (the [[Sutras]]). The [[monks]] [[debated]] details and voted on final versions. These were then committed to [[memory]] by other [[monks]], to be translated into the many [[languages]] of the [[Indian]] plains. It should be noted that [[Buddhism]] remained an [[oral tradition]] for over 200 years. | |

| − | The {{Wiki|traditionalists}}, now referred to as [[Sthaviravada]] or "way of the [[elders]]" (or, in [[Pali]], [[Theravada]]), developed a complex set of [[philosophical]] [[ideas]] beyond those elucidated by [[Buddha]]. These were collected into the [[Abhidharma]] or "[[higher teachings]]." But they, too, encouraged disagreements, so that one splinter group after another left the fold. Ultimately, 18 schools developed, each with their own interpretations of various issues, and spread all over [[India]] and {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}. Today, only the school stemming from the [[Sri Lankan]] [[Theravadan]] survives. | + | In the next few centuries, the original {{Wiki|unity}} of [[Buddhism]] began to fragment. The most significant split occurred after the [[second council]], held at [[Vaishali]] 100 years after the first. After [[debates]] between a more liberal group and {{Wiki|traditionalists}}, the liberal group left and labeled themselves the [[Mahasangha]] – "the great [[sangha]]." They would eventually evolve into the [[Mahayana tradition]] of northern {{Wiki|Asia}}. |

| + | |||

| + | The {{Wiki|traditionalists}}, now referred to as [[Sthaviravada]] or "way of the [[elders]]" (or, in [[Pali]], [[Theravada]]), developed a complex set of [[philosophical]] [[ideas]] beyond those elucidated by [[Buddha]]. These were collected into the [[Abhidharma]] or "[[higher teachings]]." But they, too, encouraged disagreements, so that one splinter group after another left the fold. Ultimately, 18 schools developed, each with their [[own]] interpretations of various issues, and spread all over [[India]] and {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}. Today, only the school stemming from the [[Sri Lankan]] [[Theravadan]] survives. | ||

[[Ashoka]] | [[Ashoka]] | ||

| − | One of the most significant events in the [[history of Buddhism]] is the chance encounter of the [[monk]] [[Nigrodha]] and the [[emperor]] [[Ashoka Maurya]]. [[Ashoka]], succeeding his father after a bloody power struggle in 268 bc, found himself deeply disturbed by the carnage he [[caused]] while suppressing a revolt in the land of the Kalingas. Meeting [[Nigrodha]] convinced [[Emperor Ashoka]] to devote himself to [[peace]]. On his orders, thousands of rock pillars were erected, bearing the words of the [[Buddha]], in the [[brahmi]] script – the first written {{Wiki|evidence}} of [[Buddhism]]. The [[third council]] of [[monks]] was held at [[Pataliputra]], the capital of [[Ashoka's | + | One of the most significant events in the [[history of Buddhism]] is the chance encounter of the [[monk]] [[Nigrodha]] and the [[emperor]] [[Ashoka Maurya]]. [[Ashoka]], succeeding his father after a bloody power struggle in 268 bc, found himself deeply disturbed by the carnage he [[caused]] while suppressing a revolt in the land of the [[Kalingas]]. Meeting [[Nigrodha]] convinced [[Emperor Ashoka]] to devote himself to [[peace]]. On his orders, thousands of rock pillars were erected, bearing the words of the [[Buddha]], in the [[brahmi]] [[script]] – the first written {{Wiki|evidence}} of [[Buddhism]]. The [[third council]] of [[monks]] was held at [[Pataliputra]], the capital of [[Ashoka's empire]]. |

| − | There is a story that tells about a poor young boy who, having nothing to give the [[Buddha]] as a [[gift]], collected a handful of dust and innocently presented it. The [[Buddha]] smiled and accepted it with the same graciousness he accepted the gifts of wealthy admirers. That boy, it is said, was [[reborn]] as the [[Emperor Ashoka]]. | + | There is a story that tells about a poor young boy who, having nothing to give the [[Buddha]] as a [[gift]], collected a handful of dust and innocently presented it. The [[Buddha]] smiled and accepted it with the same graciousness he accepted the gifts of wealthy admirers. That boy, it is said, was [[reborn]] as the [[Emperor Ashoka]]. |

| − | [[Emperor Ashoka]] sent one of his sons, [[Mahinda]], and one of his daughters, [[Sanghamitta]], a [[monk]] and a [[nun]], to [[Sri Lanka]] ([[Ceylon]]) around the year 240 bc. The [[king]] of [[Sri Lanka]], [[King]] [[Devanampiyatissa]], welcomed them and was converted. One of the gifts they brought with them was a branch of the [[bodhi tree]], which was successfully transplanted. The descendants of this branch can still be found on the island. The [[fourth council]] was held in [[Sri Lanka]], in the [[Aloka]] | + | [[Ashoka]] sent [[missionaries]] all over [[India]] and beyond. Some went as far as {{Wiki|Egypt}}, {{Wiki|Palestine}}, and {{Wiki|Greece}}. St. [[Origen]] even mentions them as having reached {{Wiki|Britain}}. The [[Greeks]] of one of the [[Alexandrian]] {{Wiki|kingdoms}} of {{Wiki|northern India}} adopted [[Buddhism]], after their [[King]] [[Menandros]] ([[Pali]]: [[Milinda]]) was convinced by a [[monk]] named [[Nagasena]] – the [[conversation]] immortalized in the [[Milinda]] Pañha. A {{Wiki|Kushan}} [[king]] of [[north]] [[India]] named [[Kanishka]] was also converted, and a council was held in [[Kashmir]] in about 100 ad. {{Wiki|Greek}} [[Buddhists]] there recorded the [[Sutras]] on {{Wiki|copper}} sheets which, unfortunately, were never recovered. It is [[interesting]] to note that there is a [[saint]] in {{Wiki|Orthodox}} [[Christianity]] named [[Josaphat]], an [[Indian]] [[king]] whose story is [[essentially]] that of the [[Buddha]]. [[Josaphat]] is [[thought]] to be a [[distortion]] of the [[word]] [[bodhisattva]]. [[Sri Lanka]] and [[Theravada]] |

| + | |||

| + | [[Emperor Ashoka]] sent one of his sons, [[Mahinda]], and one of his daughters, [[Sanghamitta]], a [[monk]] and a [[nun]], to [[Sri Lanka]] ([[Ceylon]]) around the year 240 bc. The [[king]] of [[Sri Lanka]], [[King]] [[Devanampiyatissa]], welcomed them and was converted. One of the gifts they brought with them was a branch of the [[bodhi tree]], which was successfully transplanted. The descendants of this branch can still be found on the [[island]]. The [[fourth council]] was held in [[Sri Lanka]], in the [[Aloka Cave]], in the first century bc. During this [[time]] as well, and for the first [[time]], the entire set of [[Sutras]] were recorded in the [[Pali]] [[language]] on palm leaves. This became [[Theravada's]] [[Pali Canon]], from which so much of our [[knowledge]] of [[Buddhism]] stems. It is also called the [[Tripitaka]] ([[Pali]]: [[Tipitaka]]), or [[three baskets]]: The three [[sections]] of the [[canon]] are the [[Vinaya Pitaka]] (the [[monastic]] law), the [[Sutta Pitaka]] (words of the [[Buddha]]), and the [[Abhidamma Pitaka]] (the [[philosophical]] commentaries). | ||

In a very real [[sense]], [[Sri Lanka's]] [[monks]] may be credited with saving the [[Theravada tradition]]: Although it had spread once from [[India]] all over [[southeast]] {{Wiki|Asia}}, it had nearly [[died]] out due to competition from [[Hinduism]] and {{Wiki|Islam}}, as well as [[war]] and colonialism. [[Theravada]] [[monks]] spread their [[tradition]] from [[Sri Lanka]] to [[Burma]], [[Thailand]], {{Wiki|Malaysia}}, [[Cambodia]], and [[Laos]], and from these lands to {{Wiki|Europe}} and the [[west]] generally. | In a very real [[sense]], [[Sri Lanka's]] [[monks]] may be credited with saving the [[Theravada tradition]]: Although it had spread once from [[India]] all over [[southeast]] {{Wiki|Asia}}, it had nearly [[died]] out due to competition from [[Hinduism]] and {{Wiki|Islam}}, as well as [[war]] and colonialism. [[Theravada]] [[monks]] spread their [[tradition]] from [[Sri Lanka]] to [[Burma]], [[Thailand]], {{Wiki|Malaysia}}, [[Cambodia]], and [[Laos]], and from these lands to {{Wiki|Europe}} and the [[west]] generally. | ||

| Line 77: | Line 106: | ||

[[Mahayana]] | [[Mahayana]] | ||

| − | [[Mahayana]] began in the first century bc, as a development of the Mahasangha rebellion. Their more liberal attitudes toward [[monastic]] [[tradition]] allowed the lay {{Wiki|community}} to have a greater {{Wiki|voice}} in the [[nature]] of [[Buddhism]]. For better or worse, the simpler needs of the common {{Wiki|folk}} were easier for the [[Mahayanists]] to meet. For example, the [[people]] were used to [[gods]] and heroes. | + | [[Mahayana]] began in the first century bc, as a [[development]] of the [[Mahasangha]] rebellion. Their more liberal attitudes toward [[monastic]] [[tradition]] allowed the lay {{Wiki|community}} to have a greater {{Wiki|voice}} in the [[nature]] of [[Buddhism]]. For better or worse, the simpler needs of the common {{Wiki|folk}} were easier for the [[Mahayanists]] to meet. For example, the [[people]] were used to [[gods]] and heroes. |

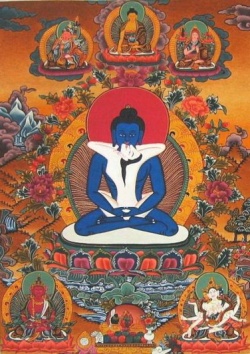

| − | + | So, the [[Trikaya]] ([[three bodies]]) [[doctrine]] came into being: Not only was [[Buddha]] a man who became [[enlightened]], he was also represented by various [[godlike]] [[Buddhas]] in various appealing [[heavens]], as well as by the [[Dharma]] itself, or [[Shunyata]] ([[emptiness]]), or [[Buddha-Mind]], depending on which [[interpretation]] we look at – sort of a [[Buddhist]] Father, Son, and {{Wiki|Holy}} [[Ghost]]! | |

| − | Shurangama-samadhi or Hero's | + | More important, however, was the increased importance of the [[Bodhisattva]]. A [[Bodhisattva]] is someone who has [[attained]] [[enlightenment]], but who chooses to remain in this [[world]] of [[Samsara]] in order to bring others to [[enlightenment]]. He is a lot like a [[saint]], a [[spiritual]] [[hero]], for the [[people]] to admire and appeal to. Along with new [[ideas]] came new [[scriptures]]. |

| + | |||

| + | Also called [[Sutras]], they are often attributed to [[Buddha]] himself, sometimes as special [[transmissions]] that [[Buddha]] supposedly felt were too difficult for his original [[listeners]] and therefore were hidden until the times were ripe. The most significant of these new [[Sutras]] are these: [[Prajñaparamita]] or [[Perfection of Wisdom]], an enormous collection of often [[esoteric]] texts, [[including]] the famous [[Heart Sutra]] and [[Diamond Sutra]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The earliest known piece of [[printing]] in the [[world]] is, in fact, a copy of the [[Diamond Sutra]], printed in [[China]] in 868 ad. [[Suddharma-pundarika]] or [[White Lotus]] of the True [[Dharma]], also often [[esoteric]], includes the [[Avalokiteshwara Sutra]], a [[prayer]] to that [[Bodhisattva]]. [[Vimalakirti-nirdesha]] or [[Vimalakirti's Exposition]], is the teachings of and stories about the [[enlightened]] [[householder]] [[Vimalakirti]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Shurangama-samadhi]] or [[Hero's Sutra]], provides a [[guide]] to [[meditation]], [[shunyata]], and the [[bodhisattva]]. It is most popular among [[Zen Buddhists]] | ||

[[Sukhavati-vyuha]] or [[Pure Land]] [[Sutra]], is the most important [[Sutra]] for the [[Pure Land]] [[Schools of Buddhism]]. The [[Buddha]] tells [[Ananda]] about [[Amitabha]] and his [[Pure Land]] or [[heaven]], and how one can be [[reborn]] there 86 There are many, many others. Finally, [[Mahayana]] is founded on two new [[philosophical]] interpretations of [[Buddhism]]: [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Yogachara]]. | [[Sukhavati-vyuha]] or [[Pure Land]] [[Sutra]], is the most important [[Sutra]] for the [[Pure Land]] [[Schools of Buddhism]]. The [[Buddha]] tells [[Ananda]] about [[Amitabha]] and his [[Pure Land]] or [[heaven]], and how one can be [[reborn]] there 86 There are many, many others. Finally, [[Mahayana]] is founded on two new [[philosophical]] interpretations of [[Buddhism]]: [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Yogachara]]. | ||

[[Madhyamaka]] | [[Madhyamaka]] | ||

| − | [[Madhyamaka]] means "the [[middle way]]." You may recall that [[Buddha]] himself called his way the [[middle way]] in his very first {{Wiki|sermon}}. He meant, at that [[time]], the [[middle way]] between the [[extremes]] of [[Wikipedia:Hedonism|hedonistic]] [[pleasure]] and extreme [[asceticism]]. But he may also have referred to the [[middle way]] between the competing [[philosophies]] of {{Wiki|eternalism}} and {{Wiki|annihilationism}} – the [[belief]] that the [[soul]] [[exists]] forever and that the [[soul]] is annihilated at [[death]]. Or between {{Wiki|materialism}} and [[nihilism]].... An [[Indian]] [[monk]] by the [[name]] of [[Nagarjuna]] took this [[idea]] and expanded on it to create the [[philosophy]] that would be known as [[Madhyamaka]], in a [[book]] called the [[Mulamadhyamaka-karika]], written about 150 ad. Basically a treatise on [[logical]] argument, it concludes that nothing is [[absolute]], everything is [[relative]], nothing [[exists]] on its own, everything is [[interdependent]]. All systems, beginning with the [[idea]] that each thing is what it is and not something else (Aristotle's law of the excluded middle), [[wind]] up contradicting themselves. Rigorous [[logic]], in other words, leads one away from all systems, and to the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[shunyata]]. [[Shunyata]] means [[emptiness]]. This doesn't mean that nothing [[exists]]. It means that nothing [[exists]] in and of itself, but only as a part of a [[universal]] web of being. This would become a central {{Wiki|concept}} in all branches of [[Mahayana]]. Of course, it is actually a restatement of the central [[Buddhist]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of [[anatman]], [[anitya]], and [[dukkha]]! | + | [[Madhyamaka]] means "the [[middle way]]." You may recall that [[Buddha]] himself called his way the [[middle way]] in his very first {{Wiki|sermon}}. He meant, at that [[time]], the [[middle way]] between the [[extremes]] of [[Wikipedia:Hedonism|hedonistic]] [[pleasure]] and extreme [[asceticism]]. But he may also have referred to the [[middle way]] between the competing [[philosophies]] of {{Wiki|eternalism}} and {{Wiki|annihilationism}} – the [[belief]] that the [[soul]] [[exists]] forever and that the [[soul]] is {{Wiki|annihilated}} at [[death]]. |

| + | |||

| + | Or between {{Wiki|materialism}} and [[nihilism]].... An [[Indian]] [[monk]] by the [[name]] of [[Nagarjuna]] took this [[idea]] and expanded on it to create the [[philosophy]] that would be known as [[Madhyamaka]], in a [[book]] called the [[Mulamadhyamaka-karika]], written about 150 ad. Basically a treatise on [[logical]] argument, it concludes that nothing is [[absolute]], everything is [[relative]], nothing [[exists]] on its [[own]], everything is [[interdependent]]. All systems, beginning with the [[idea]] that each thing is what it is and not something else ([[Aristotle's]] law of the excluded middle), [[wind]] up contradicting themselves. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rigorous [[logic]], in other words, leads one away from all systems, and to the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[shunyata]]. [[Shunyata]] means [[emptiness]]. This doesn't mean that nothing [[exists]]. It means that nothing [[exists]] in and of itself, but only as a part of a [[universal]] web of being. This would become a central {{Wiki|concept}} in all branches of [[Mahayana]]. Of course, it is actually a restatement of the central [[Buddhist]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of [[anatman]], [[anitya]], and [[dukkha]]! | ||

[[Yogachara]] | [[Yogachara]] | ||

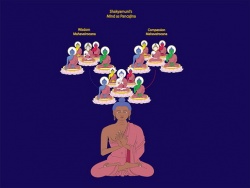

| − | The second [[philosophical]] innovation, [[Yogachara]], is credited to two brothers, [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]], who lived in [[India]] in the 300's ad. They elaborated earlier movements in the [[direction]] of the [[philosophy]] of {{Wiki|idealism}} or chitta-matra. Chitta-matra means literally [[mind only]]. [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]] believed that everything that [[exists]] is [[mind]] or [[consciousness]]. What we think of as [[physical]] things are just {{Wiki|projections}} of our [[minds]], [[delusions]] or hallucinations, if you like. To get rid of these [[delusions]], we must [[meditate]], which for the [[Yogachara school]] means the creation of [[pure consciousness]], devoid of all content. In that way, we leave our deluded {{Wiki|individual}} [[minds]] and join with the [[universal]] [[mind]], or [[Buddha-mind]]. | + | The second [[philosophical]] innovation, [[Yogachara]], is credited to two brothers, [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]], who lived in [[India]] in the 300's ad. They elaborated earlier movements in the [[direction]] of the [[philosophy]] of {{Wiki|idealism}} or [[chitta-matra]]. [[Chitta-matra]] means literally [[mind only]]. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]] believed that everything that [[exists]] is [[mind]] or [[consciousness]]. What we think of as [[physical]] things are just {{Wiki|projections}} of our [[minds]], [[delusions]] or [[hallucinations]], if you like. To get rid of these [[delusions]], we must [[meditate]], which for the [[Yogachara school]] means the creation of [[pure consciousness]], devoid of all content. In that way, we leave our deluded {{Wiki|individual}} [[minds]] and join with the [[universal]] [[mind]], or [[Buddha-mind]]. | ||

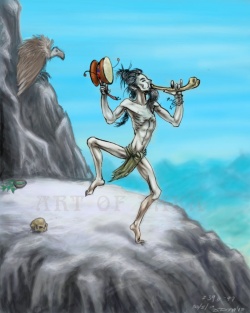

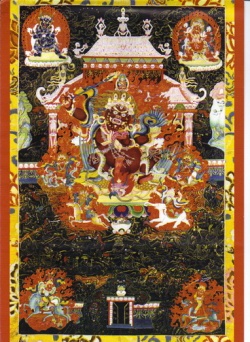

[[Tantra]] | [[Tantra]] | ||

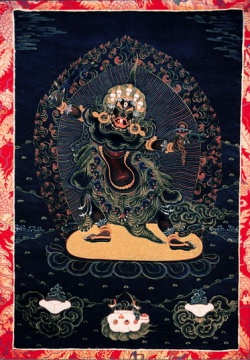

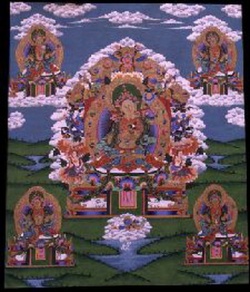

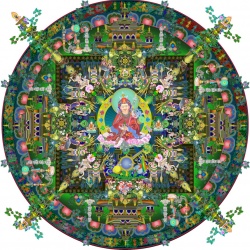

| − | The last innovation was less [[philosophical]] and far more practical: [[Tantra]]. [[Tantra]] refers to certain writings which are concerned, not with [[philosophical]] niceties, but with the basic how-to of [[enlightenment]], and not just with [[enlightenment]] in several [[rebirths]], but [[enlightenment]] here-and-now! In order to accomplish this feat, dramatic methods are needed, ones which, to the uninitiated, may seem rather bizarre. [[Tantra]] was the domain of the siddhu, the {{Wiki|adept}} – someone who [[knows]] the secrets, a [[Wikipedia:Magician(paranormal)|magician]] in the ways of [[enlightenment]]. [[Tantra]] involves the use of various | + | The last innovation was less [[philosophical]] and far more {{Wiki|practical}}: [[Tantra]]. [[Tantra]] refers to certain writings which are concerned, not with [[philosophical]] niceties, but with the basic how-to of [[enlightenment]], and not just with [[enlightenment]] in several [[rebirths]], but [[enlightenment]] here-and-now! In order to [[accomplish]] this feat, dramatic [[methods]] are needed, ones which, to the uninitiated, may seem rather bizarre. [[Tantra]] was the domain of the [[siddhu]], the {{Wiki|adept}} – someone who [[knows]] the secrets, a [[Wikipedia:Magician(paranormal)|magician]] in the ways of [[enlightenment]]. [[Tantra]] involves the use of various [[techniques]], [[including]] the well-known [[mandalas]], [[mantras]], and [[mudras]]. |

| − | These [[ideas]] would have enormous impact on [[Mahayana]]. They are not without critics, however: [[Madhyamaka]] is sometimes criticized as word-play, and [[Yogachara]] is criticized as reintroducing [[atman]], [[eternal]] [[soul]] or [[essence]], to [[Buddhism]]. [[Tantra]] has been most often criticized, especially for its emphasis on secret methods and strong [[devotion]] to a [[guru]]. Nevertheless, these innovations led to a renewed flurry of [[activity]] in the first half of the first millenium, and provided the foundation for the kinds of [[Buddhism]] we find in [[China]], [[Tibet]], [[Japan]], [[Korea]], [[Vietnam]], and elsewhere in [[east]] {{Wiki|Asia}}. [[China]] | + | [[mandalas]] are paintings or other {{Wiki|representations}} of higher [[awareness]], usually in the [[form]] of a circular pattern of images, which may provide the focus of [[one-pointed meditation]]. [[Mantras]] are words or phrases that serve the same {{Wiki|purpose}}, such as the famous "[[Om mani padme hum]]." [[Mudras]] are hand positions that [[symbolize]] certain qualities of [[enlightenment]]. Less well known are the [[yidams]]. A [[yidam]] is the image of a [[god]] or [[goddess]] or other [[spiritual being]], either {{Wiki|physically}} represented or, more commonly, [[imagined]] clearly in the [[mind's eye]]. Again, these represent {{Wiki|archetypal}} qualities of [[enlightenment]], and [[one-pointed meditation]] on these complex images lead the {{Wiki|adept}} to his or her goal. |

| + | |||

| + | These [[ideas]] would have enormous impact on [[Mahayana]]. They are not without critics, however: [[Madhyamaka]] is sometimes criticized as word-play, and [[Yogachara]] is criticized as reintroducing [[atman]], [[eternal]] [[soul]] or [[essence]], to [[Buddhism]]. [[Tantra]] has been most often criticized, especially for its {{Wiki|emphasis}} on secret [[methods]] and strong [[devotion]] to a [[guru]]. Nevertheless, these innovations led to a renewed flurry of [[activity]] in the first half of the first millenium, and provided the foundation for the kinds of [[Buddhism]] we find in [[China]], [[Tibet]], [[Japan]], [[Korea]], [[Vietnam]], and elsewhere in [[east]] {{Wiki|Asia}}. [[China]] | ||

Legend has it that the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Wikipedia:Emperor Ming of Han|Emperor Ming]] Ti had a [[dream]] which led him to send his agents down the [[Silk Road]] – the {{Wiki|ancient}} trade route between [[China]] and the [[west]] – to discover its meaning. The agents returned with a picture of the [[Buddha]] and a copy of the [[Sutra]] in 42 [[Sections]]. This [[Sutra]] would, in 67 ad, be the first of many to be translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. | Legend has it that the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Wikipedia:Emperor Ming of Han|Emperor Ming]] Ti had a [[dream]] which led him to send his agents down the [[Silk Road]] – the {{Wiki|ancient}} trade route between [[China]] and the [[west]] – to discover its meaning. The agents returned with a picture of the [[Buddha]] and a copy of the [[Sutra]] in 42 [[Sections]]. This [[Sutra]] would, in 67 ad, be the first of many to be translated into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. | ||

| − | The first [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}} in [[China]] is [[thought]] to be one in [[Loyang]], established by "foreigners" around 150 ad, in the {{Wiki|Han dynasty}}. Only 100 years later, there emerges a native {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Sangha]]. And during the Period of Disunity (or {{Wiki|Era}} of the Warring States, 220 to 589 ad), the number of [[Buddhist]] [[monks and nuns]] increase to as many as two million! Apparently, the uncertain times and the [[misery]] of the lower classes were {{Wiki|fertile}} ground for the [[monastic]] [[traditions]] of [[Buddhism]]. [[Buddhism]] did not come to a land innocent of [[religion]] and [[philosophy]], of course. [[China]], in fact, had three main competing streams of [[thought]]: [[Wikipedia:Confucianism|Confucianism]], {{Wiki|Taoism}}, and {{Wiki|folk}} [[religion]]. | + | The first [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}} in [[China]] is [[thought]] to be one in [[Loyang]], established by "foreigners" around 150 ad, in the {{Wiki|Han dynasty}}. Only 100 years later, there emerges a native {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Sangha]]. |

| + | |||

| + | And during the {{Wiki|Period of Disunity}} (or {{Wiki|Era}} of the Warring States, 220 to 589 ad), the number of [[Buddhist]] [[monks and nuns]] increase to as many as two million! Apparently, the uncertain times and the [[misery]] of the lower classes were {{Wiki|fertile}} ground for the [[monastic]] [[traditions]] of [[Buddhism]]. [[Buddhism]] did not come to a land innocent of [[religion]] and [[philosophy]], of course. [[China]], in fact, had three main competing streams of [[thought]]: [[Wikipedia:Confucianism|Confucianism]], {{Wiki|Taoism}}, and {{Wiki|folk}} [[religion]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Confucianism]] is [[essentially]] a moral-political [[philosophy]], involving a complex [[guide]] to [[human]] relationships. {{Wiki|Taoism}} is a life-philosophy involving a return to simpler and more "natural" ways of being. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And the {{Wiki|folk}} [[religion]] – or, should we say, [[religions]] – consisted of rich {{Wiki|mythologies}}, {{Wiki|superstitions}}, [[astrology]], reading of entrails, [[magic]], {{Wiki|folk}} [[medicine]], and so on. (Please understand that I am simplifying here: Certainly [[Wikipedia:Confucianism|Confucianism]] and {{Wiki|Taoism}} are as sophisticated as [[Buddhism]]!) | ||

Although these various streams sometimes competed with each other and with [[Buddhism]], they also fed each other, enriched each other, and intertwined with each other. Over [[time]], the [[Mahayana]] of [[India]] became the [[Mahayana]] of [[China]] and, later, of [[Korea]], [[Japan]], and [[Vietnam]]. | Although these various streams sometimes competed with each other and with [[Buddhism]], they also fed each other, enriched each other, and intertwined with each other. Over [[time]], the [[Mahayana]] of [[India]] became the [[Mahayana]] of [[China]] and, later, of [[Korea]], [[Japan]], and [[Vietnam]]. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 155: | ||

[[Pure Land]] | [[Pure Land]] | ||

| − | The first example historically is [[Pure Land Buddhism]] ([[Ching-T'u]], J: [[Jodo]]). The peasants and working [[people]] of [[China]] were used to [[gods]] and [[goddesses]], praying for [[rain]] and health, worrying about [[heaven]] and [[hell]], and so on. It wasn't a great leap to find in [[Buddhism's]] [[cosmology]] and {{Wiki|theology}} the bases for a [[religious]] [[tradition]] that catered to these needs and [[habits]], while still providing a sophisticated [[philosophical]] foundation. The [[idea]] of this period of [[time]] as a fallen or {{Wiki|inferior}} [[time]] – [[traditional]] in [[China]] – led to the [[idea]] that we are no longer able to reach [[enlightenment]] on our own power, but must rely on the intercession of higher [[beings]]. 86 The [[transcendent]] [[Buddha Amitabha]], and his [[western paradise]] ("[[pure land]]"), introduced in the [[Sukhavativyuha Sutra]], was a perfect fit. | + | The first example historically is [[Pure Land Buddhism]] ([[Ching-T'u]], J: [[Jodo]]). The peasants and working [[people]] of [[China]] were used to [[gods]] and [[goddesses]], praying for [[rain]] and [[health]], worrying about [[heaven]] and [[hell]], and so on. It wasn't a great leap to find in [[Buddhism's]] [[cosmology]] and {{Wiki|theology}} the bases for a [[religious]] [[tradition]] that catered to these needs and [[habits]], while still providing a sophisticated [[philosophical]] foundation. The [[idea]] of this period of [[time]] as a fallen or {{Wiki|inferior}} [[time]] – [[traditional]] in [[China]] – led to the [[idea]] that we are no longer able to reach [[enlightenment]] on our [[own]] power, but must rely on the intercession of higher [[beings]]. 86 The [[transcendent]] [[Buddha Amitabha]], and his [[western paradise]] ("[[pure land]]"), introduced in the [[Sukhavativyuha Sutra]], was a {{Wiki|perfect}} fit. |

[[Ch'an]] | [[Ch'an]] | ||

Another school that was to be particularly strongly influenced by {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[thought]] was the [[Meditation School]] – [[Dhyana]], [[Ch'an]], Son, or [[Zen]]. [[Tradition]] has the [[Indian]] [[monk]] [[Bodhidharma]] coming from the [[west]] to [[China]] around 520 ad. It was [[Bodhidharma]], it is said, who carried the [[Silent]] [[Transmission]] to become the [[First Patriarch]] of the [[Ch'an School]] in [[China]]: | Another school that was to be particularly strongly influenced by {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[thought]] was the [[Meditation School]] – [[Dhyana]], [[Ch'an]], Son, or [[Zen]]. [[Tradition]] has the [[Indian]] [[monk]] [[Bodhidharma]] coming from the [[west]] to [[China]] around 520 ad. It was [[Bodhidharma]], it is said, who carried the [[Silent]] [[Transmission]] to become the [[First Patriarch]] of the [[Ch'an School]] in [[China]]: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

From the very beginning, [[Buddha]] had had reservations about his ability to {{Wiki|communicate}} his message to the [[people]]. Words simply could not carry such a [[sublime]] message. So, on one occasion, while the [[monks]] around him waited for a {{Wiki|sermon}}, he said absolutely nothing. He simply held up a [[flower]]. the [[monks]], of course, were confused, except for [[Kashyapa]], who understood and smiled. The [[Buddha]] smiled back, and thus the [[Silent]] [[Transmission]] began. | From the very beginning, [[Buddha]] had had reservations about his ability to {{Wiki|communicate}} his message to the [[people]]. Words simply could not carry such a [[sublime]] message. So, on one occasion, while the [[monks]] around him waited for a {{Wiki|sermon}}, he said absolutely nothing. He simply held up a [[flower]]. the [[monks]], of course, were confused, except for [[Kashyapa]], who understood and smiled. The [[Buddha]] smiled back, and thus the [[Silent]] [[Transmission]] began. | ||

| − | [[Zen Buddhism]] focuses on developing the immediate [[awareness]] of [[Buddha-mind]] through [[meditation]] on [[emptiness]]. It is notorious for its dismissal of the written and spoken [[word]] and occasionally for his roughhouse antics. It should be understood, however, that there is great reverence for the [[Buddha]], the [[Dharma]], and the [[Sangha]], even when they are ostensibly ignoring, poking fun, or even turning them upside-down. [[Zen]] has contributed its own {{Wiki|literature}} to the [[Buddhist]] melting-pot, including The [[Platform Sutra]], written by [[Hui Neng]], the [[Sixth Patriarch]], around 700 ad., The [[Blue Cliff Record]], written about 1000 ad., and The Gateless Gate, written about 1200 ad. And we shouldn't forget the famous Ten Ox-Herding Pictures that many see as containing the very [[essence]] of Zen's message. | + | [[Zen Buddhism]] focuses on developing the immediate [[awareness]] of [[Buddha-mind]] through [[meditation]] on [[emptiness]]. It is notorious for its dismissal of the written and spoken [[word]] and occasionally for his roughhouse antics. It should be understood, however, that there is great reverence for the [[Buddha]], the [[Dharma]], and the [[Sangha]], even when they are ostensibly ignoring, poking fun, or even turning them upside-down. [[Zen]] has contributed its [[own]] {{Wiki|literature}} to the [[Buddhist]] melting-pot, [[including]] The [[Platform Sutra]], written by [[Hui Neng]], the [[Sixth Patriarch]], around 700 ad., The [[Blue Cliff Record]], written about 1000 ad., and The [[Gateless Gate]], written about 1200 ad. And we shouldn't forget the famous [[Wikipedia:Ten Bulls|Ten Ox-Herding Pictures]] that many see as containing the very [[essence]] of [[Zen's]] message. |

The Blossoming of Schools | The Blossoming of Schools | ||

| Line 119: | Line 170: | ||

During the {{Wiki|Sui dynasty}} (581-618) and [[Wikipedia:Tang Dynasty|T'ang dynasty]] (618-907), [[Chinese Buddhism]] [[experienced]] what is referred to as the "blossoming of schools." The [[philosophical]] inspirations of the [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Yogachara]], as well as the [[Pure Land]] and [[Ch'an]] [[Sutras]], interacting with the already sophisticated [[philosophies]] of [[Wikipedia:Confucianism|Confucianism]] and {{Wiki|Taoism}}, led to a regular {{Wiki|renaissance}} in [[religious]] and [[philosophical]] [[thought]]. | During the {{Wiki|Sui dynasty}} (581-618) and [[Wikipedia:Tang Dynasty|T'ang dynasty]] (618-907), [[Chinese Buddhism]] [[experienced]] what is referred to as the "blossoming of schools." The [[philosophical]] inspirations of the [[Madhyamaka]] and [[Yogachara]], as well as the [[Pure Land]] and [[Ch'an]] [[Sutras]], interacting with the already sophisticated [[philosophies]] of [[Wikipedia:Confucianism|Confucianism]] and {{Wiki|Taoism}}, led to a regular {{Wiki|renaissance}} in [[religious]] and [[philosophical]] [[thought]]. | ||

| − | We find the Realistic School, based on the "all things [[exist]]" [[Hinayana]] School; the Three-Treatises School, based on [[Madhyamaka]]; the Idealist School, based on [[Yogachara]]; the [[Tantric]] School; the [[Flower Adornment]] School ([[Hua-Yen]], J: [[Kegon]]), which attempted to consolidate the various [[forms]]; and the [[White Lotus]] School ([[T'ien-T'ai]], J: [[Tendai]]), which focused on the [[Lotus Sutra]]. All the {{Wiki|Chinese}} Schools had their representatives in neighboring countries. [[Korea]] was to develop its own powerful [[form]] of [[Ch'an]] called Son. [[Vietnam]] developed a [[form]] of [[Ch'an]] that incorporated aspects of [[Pure Land]] and [[Hinayana]]. But it was [[Japan]] that would have a field day with [[Chinese Buddhism]], and pass the [[Mahayana]] [[traditions]] on to the US and the [[west]] generally. | + | We find the Realistic School, based on the "all things [[exist]]" [[Hinayana]] School; the Three-Treatises School, based on [[Madhyamaka]]; the Idealist School, based on [[Yogachara]]; the [[Tantric]] School; the [[Flower Adornment]] School ([[Hua-Yen]], J: [[Kegon]]), which attempted to consolidate the various [[forms]]; and the [[White Lotus]] School]] ([[T'ien-T'ai]], J: [[Tendai]]), which focused on the [[Lotus Sutra]]. All the {{Wiki|Chinese}} Schools had their representatives in neighboring countries. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Korea]] was to develop its [[own]] powerful [[form]] of [[Ch'an]] called Son. [[Vietnam]] developed a [[form]] of [[Ch'an]] that incorporated aspects of [[Pure Land]] and [[Hinayana]]. But it was [[Japan]] that would have a field day with [[Chinese Buddhism]], and pass the [[Mahayana]] [[traditions]] on to the US and the [[west]] generally. | ||

86 [[Japan]] | 86 [[Japan]] | ||

| − | Again, we begin with the legendary: A delegation arrived from [[Korea]] with gifts for the [[Emperor]] of [[Japan]] in 538 ad., including a bronze [[Buddha]] and various [[Sutras]]. Unfortunately a plague led the [[Emperor]] to believe that the [[traditional]] [[gods]] of [[Japan]] were annoyed, so he had the gifts thrown into a canal! But the {{Wiki|imperial court}} on the 600's, in their [[constant]] [[effort]] to be as sophisticated as the courts of their distinguished neighbors, the {{Wiki|Chinese}}, continued to be drawn to [[Buddhism]]. Although starting as a [[religion]] of the upper classes, in the 900's, [[Pure Land]] entered the picture as the favorite of the peasant and working classes. And in the 1200's, [[Ch'an]], relabeled [[Zen]], came into [[Japan]], where it was enthusiastically adopted by, among others, the [[warrior]] class or {{Wiki|Samurai}}. [[Zen]] was introduced into [[Japan]] by two particularly talented [[monks]] who had gone to [[China]] for their educations: | + | Again, we begin with the legendary: A delegation arrived from [[Korea]] with gifts for the [[Emperor]] of [[Japan]] in 538 ad., [[including]] a bronze [[Buddha]] and various [[Sutras]]. Unfortunately a plague led the [[Emperor]] to believe that the [[traditional]] [[gods]] of [[Japan]] were annoyed, so he had the gifts thrown into a canal! But the {{Wiki|imperial court}} on the 600's, in their [[constant]] [[effort]] to be as sophisticated as the courts of their {{Wiki|distinguished}} neighbors, the {{Wiki|Chinese}}, continued to be drawn to [[Buddhism]]. |

| + | |||

| + | Although starting as a [[religion]] of the upper classes, in the 900's, [[Pure Land]] entered the picture as the favorite of the peasant and working classes. And in the 1200's, [[Ch'an]], relabeled [[Zen]], came into [[Japan]], where it was enthusiastically adopted by, among others, the [[warrior]] class or {{Wiki|Samurai}}. [[Zen]] was introduced into [[Japan]] by two particularly talented [[monks]] who had gone to [[China]] for their educations: | ||

| − | In [[China]] and elsewhere, a certain simple, elegant style of [[writing]] and drawing developed among the [[monks]]. In [[Japan]], this became an even more influential aspect of [[Zen]]. We have, for example, the [[poetry]], {{Wiki|calligraphy}}, and paintings of various [[monks]] – [[Bankei]] (1622-1698), Basho (1644-1694), [[Hakuin]] (1685-1768), and Ryokan (1758-1831) – which have become internationally beloved. One last [[Japanese]] innovation is usually attributed to a somewhat unorthodox [[monk]] named [[Nichiren]] (1222- 1282). Having been trained in the [[Tendai]] or [[White Lotus]] [[tradition]], he came to believe that the [[Lotus Sutra]] carried all that was necessary for [[Buddhist]] [[life]]. More than that, he believed that even the [[name]] of the [[Sutra]] was enough! So he encouraged his students to [[chant]] this [[mantra]]: Namu-myoho-renge-kyo, which means "homage to the [[Lotus Sutra]]." This practice alone would ensure [[enlightenment]] in this [[life]]. In fact, he insisted, all other [[forms]] of [[Buddhism]] were of little worth. Needless to say, this was not appreciated by the [[Buddhist]] [[powers]] of the day. He spent the rest of his [[life]] in [[relative]] isolation. The [[Nichiren School]] nevertheless proved to be one of the most successful [[forms]] of [[Buddhism]] on the {{Wiki|planet}}! | + | [[Eisai]] (1141-1215) brought [[Lin-chi]] (J: [[Rinzai]]) [[Ch'an]], with its [[koans]] and occasionally outrageous antics; [[Dogen]] (1200-1253) brought the more sedate [[Ts'ao-tung]] (J: [[Soto]]) [[Ch'an]]. In addition, [[Dogen]] is particularly admired for his massive treatise, the [[Shobogenzo]]. [[Ch'an]] has always had an artistic side to it. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In [[China]] and elsewhere, a certain simple, elegant style of [[writing]] and drawing developed among the [[monks]]. In [[Japan]], this became an even more influential aspect of [[Zen]]. We have, for example, the [[poetry]], {{Wiki|calligraphy}}, and paintings of various [[monks]] – [[Bankei]] (1622-1698), Basho (1644-1694), [[Hakuin]] (1685-1768), and [[Ryokan]] (1758-1831) – which have become internationally beloved. One last [[Japanese]] innovation is usually attributed to a somewhat [[unorthodox]] [[monk]] named [[Nichiren]] (1222- 1282). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Having been trained in the [[Tendai]] or [[White Lotus]] [[tradition]], he came to believe that the [[Lotus Sutra]] carried all that was necessary for [[Buddhist]] [[life]]. More than that, he believed that even the [[name]] of the [[Sutra]] was enough! So he encouraged his students to [[chant]] this [[mantra]]: [[Namu-myoho-renge-kyo]], which means "homage to the [[Lotus Sutra]]." This practice alone would ensure [[enlightenment]] in this [[life]]. In fact, he insisted, all other [[forms]] of [[Buddhism]] were of little worth. Needless to say, this was not appreciated by the [[Buddhist]] [[powers]] of the day. He spent the rest of his [[life]] in [[relative]] isolation. The [[Nichiren School]] nevertheless proved to be one of the most successful [[forms]] of [[Buddhism]] on the {{Wiki|planet}}! | ||

[[Tibet]] | [[Tibet]] | ||

| − | Finally, let's turn out [[attention]] to the most mysterious site of [[Buddhism's]] history, [[Tibet]]. Its first encounter with [[Buddhism]] occurred in the 700's ad, when a [[Tantric]] [[master]], [[Guru]] [[Rinpoché]], came from [[India]] to battle the {{Wiki|demons}} of [[Tibet]] for control. The {{Wiki|demons}} submitted, but they remained forever a part of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] – as its [[protectors]]! | + | Finally, let's turn out [[attention]] to the most mysterious site of [[Buddhism's]] history, [[Tibet]]. Its first encounter with [[Buddhism]] occurred in the 700's ad, when a [[Tantric]] [[master]], [[Guru]] [[Rinpoché]], came from [[India]] to {{Wiki|battle}} the {{Wiki|demons}} of [[Tibet]] for control. The {{Wiki|demons}} submitted, but they remained forever a part of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] – as its [[protectors]]! |

| + | |||

| + | |||

During the 800's and 900's, [[Tibet]] went through a "dark age," during which [[Buddhism]] [[suffered]] something of a setback. But, in the 1000's, it returned in force. And in 1578, the {{Wiki|Mongol}} overlords named the head of the [[Gelug School]] the [[Dalai Lama]], meaning "[[guru]] as great as the ocean." The title was made retroactive to two earlier heads of the school. The [[fifth Dalai Lama]] is noted for bringing all of [[Tibet]] under his [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} control. | During the 800's and 900's, [[Tibet]] went through a "dark age," during which [[Buddhism]] [[suffered]] something of a setback. But, in the 1000's, it returned in force. And in 1578, the {{Wiki|Mongol}} overlords named the head of the [[Gelug School]] the [[Dalai Lama]], meaning "[[guru]] as great as the ocean." The title was made retroactive to two earlier heads of the school. The [[fifth Dalai Lama]] is noted for bringing all of [[Tibet]] under his [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} control. | ||

The [[lineage]] continues down to the {{Wiki|present}} [[14th Dalai Lama]], [[Tenzin Gyatso]], born 1935. In 1989, he was awarded the {{Wiki|Nobel}} [[Peace]] Prize for his efforts on behalf of his [[people]] and {{Wiki|nation}}, which had been taken over by the {{Wiki|Communist}} {{Wiki|Chinese}} in 1951. | The [[lineage]] continues down to the {{Wiki|present}} [[14th Dalai Lama]], [[Tenzin Gyatso]], born 1935. In 1989, he was awarded the {{Wiki|Nobel}} [[Peace]] Prize for his efforts on behalf of his [[people]] and {{Wiki|nation}}, which had been taken over by the {{Wiki|Communist}} {{Wiki|Chinese}} in 1951. | ||

| − | + | The [[West]] | |

| − | |||

| − | In {{Wiki|England}}, for example, {{Wiki|societies}} sprang up for {{Wiki|devotees}} of "orientalia," such as T. W. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}}' [[Pali Text Society]] and T. {{Wiki|Christmas Humphreys}}' [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}}. [[Books]] were published, such as Sir Edwin Arnold's epic poem The Light of | + | It was in the [[latter]] half of the 1800's that [[Buddhism]] first came to be known in the [[west]]. The great {{Wiki|European}} colonial empires brought the {{Wiki|ancient}} cultures of [[India]] and [[China]] back to the [[attention]] of the intellectuals of {{Wiki|Europe}}. [[Scholars]] began to learn {{Wiki|Asian}} [[languages]] and translate {{Wiki|Asian}} texts. Adventurers explored previously shut-off places and recorded the cultures. [[Religious]] enthusiasts enjoyed the exotic and [[mystical]] tone of the {{Wiki|Asian}} [[traditions]]. |

| + | |||

| + | In {{Wiki|England}}, for example, {{Wiki|societies}} sprang up for {{Wiki|devotees}} of "orientalia," such as T. W. {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}}' [[Pali Text Society]] and T. {{Wiki|Christmas Humphreys}}' [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Society}}. [[Books]] were published, such as Sir [[Edwin Arnold's]] {{Wiki|epic}} poem [[The Light of Asia]] (1879). And the first {{Wiki|western}} [[monks]] began to make themselves know, such as [[Allan Bennett]], perhaps the very first, who took the [[name]] [[Ananda Metteya]]. In {{Wiki|Germany}} and {{Wiki|France}} as well, [[Buddhism]] was the [[rage]]. | ||

In the [[United States]], there was a similar flurry of [[interest]]. First of all, thousands of {{Wiki|Chinese}} immigrants were coming to the [[west]] coast in the late 1800's, many to provide cheap labor for the railroads and other expanding industries. Also, on the [[east]] coast, intellectuals were reading about [[Buddhism]] in [[books]] by {{Wiki|Europeans}}. One example was Henry Thoreau, who, among other things, translated a {{Wiki|French}} translation of a [[Buddhist]] [[Sutra]] into English. | In the [[United States]], there was a similar flurry of [[interest]]. First of all, thousands of {{Wiki|Chinese}} immigrants were coming to the [[west]] coast in the late 1800's, many to provide cheap labor for the railroads and other expanding industries. Also, on the [[east]] coast, intellectuals were reading about [[Buddhism]] in [[books]] by {{Wiki|Europeans}}. One example was Henry Thoreau, who, among other things, translated a {{Wiki|French}} translation of a [[Buddhist]] [[Sutra]] into English. | ||

| − | A renewal of [[interest]] came during {{Wiki|World War II}}, during which many {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhists]] – such as the [[Zen]] author {{Wiki|D. T. Suzuki}} – came to {{Wiki|England}} and the U.S., and many {{Wiki|European}} [[Buddhists]] – such as the [[Zen]] author {{Wiki|Alan Watts}} – came to the U.S. As these examples suggest, [[Zen Buddhism]] was particularly popular, especially in the U.S., where it became enmeshed in the Beatnik artistic and {{Wiki|literary}} {{Wiki|movement}} as "beat [[Zen]]." | + | A renewal of [[interest]] came during {{Wiki|World War II}}, during which many {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhists]] – such as the [[Zen]] author {{Wiki|D. T. Suzuki}} – came to {{Wiki|England}} and the U.S., and many {{Wiki|European}} [[Buddhists]] – such as the [[Zen]] author {{Wiki|Alan Watts}} – came to the [[U.S]]. As these examples suggest, [[Zen Buddhism]] was particularly popular, especially in the U.S., where it became enmeshed in the Beatnik artistic and {{Wiki|literary}} {{Wiki|movement}} as "beat [[Zen]]." |

One by one, {{Wiki|European}} and {{Wiki|Americans}} who studied in {{Wiki|Asia}} returned with their [[knowledge]] and founded [[monasteries]] and {{Wiki|societies}}, {{Wiki|Asian}} [[masters]] came to {{Wiki|Europe}} and {{Wiki|America}} to found [[monasteries]], and the {{Wiki|Asian}} immigrant populations from [[China]], [[Japan]], [[Vietnam]] and elsewhere, quietly continued their [[Buddhist practices]]. | One by one, {{Wiki|European}} and {{Wiki|Americans}} who studied in {{Wiki|Asia}} returned with their [[knowledge]] and founded [[monasteries]] and {{Wiki|societies}}, {{Wiki|Asian}} [[masters]] came to {{Wiki|Europe}} and {{Wiki|America}} to found [[monasteries]], and the {{Wiki|Asian}} immigrant populations from [[China]], [[Japan]], [[Vietnam]] and elsewhere, quietly continued their [[Buddhist practices]]. | ||

| − | Today, it is believed that there are more than 300 million [[Buddhists in the world]], including at least a quarter million in {{Wiki|Europe}}, and a half million each in [[North]] and {{Wiki|South America}}. I say "at least" because other estimates go as high as three million in the U.S. alone! Whatever the numbers may be, [[Buddhism]] is the fourth largest [[religion]] in the [[world]], after [[Christianity]], {{Wiki|Islam}}, and [[Hinduism]]. And, although it has [[suffered]] considerable setbacks over the centuries, it seems to be attracting more and more [[people]], as a [[religion]] or a [[philosophy]] of [[life]]. | + | Today, it is believed that there are more than 300 million [[Buddhists in the world]], [[including]] at least a quarter million in {{Wiki|Europe}}, and a half million each in [[North]] and {{Wiki|South America}}. I say "at least" because other estimates go as high as three million in the [[U.S.]] alone! Whatever the numbers may be, [[Buddhism]] is [[the fourth]] largest [[religion]] in the [[world]], after [[Christianity]], {{Wiki|Islam}}, and [[Hinduism]]. And, although it has [[suffered]] considerable setbacks over the centuries, it seems to be attracting more and more [[people]], as a [[religion]] or a [[philosophy]] of [[life]]. |

The [[Dharma]] incomparably profound and exquisite | The [[Dharma]] incomparably profound and exquisite | ||

| Line 159: | Line 222: | ||

I [[take refuge]] in the [[Sangha]]. | I [[take refuge]] in the [[Sangha]]. | ||

I [[take refuge]] in the [[Buddha]], the incomparably honoured one; I [[take refuge]] in the [[Dharma]], honourable for its [[purity]]; I [[take refuge]] in the [[Sangha]], honourable for its harmonious [[life]]. I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Buddha]]; | I [[take refuge]] in the [[Buddha]], the incomparably honoured one; I [[take refuge]] in the [[Dharma]], honourable for its [[purity]]; I [[take refuge]] in the [[Sangha]], honourable for its harmonious [[life]]. I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Buddha]]; | ||

| + | |||

I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Dharma]]; | I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Dharma]]; | ||

I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Sangha]]. | I have finished [[taking refuge]] in the [[Sangha]]. | ||

| + | |||

The [[Four Great Vows]] | The [[Four Great Vows]] | ||

| − | However innumerable [[beings]] are, I [[vow]] to save them; However inexhaustible the [[passions]] are, I [[vow]] to extinguish them; However [[immeasurable]] the [[Dharmas]] are, I [[vow]] to [[master]] them; However incomparable the Buddha-truth is, I [[vow]] to attain it. The [[Teaching | + | However {{Wiki|innumerable}} [[beings]] are, I [[vow]] to save them; However inexhaustible the [[passions]] are, I [[vow]] to extinguish them; However [[immeasurable]] the [[Dharmas]] are, I [[vow]] to [[master]] them; However incomparable the [[Buddha-truth]] is, I [[vow]] to attain it. The [[Teaching of the Seven Buddhas]] |

Not to commit [[evils]], | Not to commit [[evils]], | ||

| Line 174: | Line 239: | ||

They are [[subject]] to [[birth]] and [[death]]; | They are [[subject]] to [[birth]] and [[death]]; | ||

Put an end to [[birth]] and [[death]], | Put an end to [[birth]] and [[death]], | ||

| − | And there is blissful [[tranquility]].* | + | And there is [[blissful]] [[tranquility]].* |

* The preceding quoted in {{Wiki|D. T. Suzuki}}, Manual of [[Zen Buddhism]]. N.Y.: Grove, 1960. | * The preceding quoted in {{Wiki|D. T. Suzuki}}, Manual of [[Zen Buddhism]]. N.Y.: Grove, 1960. | ||

| − | 86 | + | 86 [[Mahamangala Sutta]]* |

| − | [{{Wiki|Discourse}} of Supreme [[Happiness]] | + | [{{Wiki|Discourse}} of Supreme [[Happiness]]) |

[[Pali]] | [[Pali]] | ||

| − | Bahu [[deva]] [[manussa]] ca | + | [[Bahu]] [[deva]] [[manussa]] ca |

Mangalani acintayum | Mangalani acintayum | ||

Akankha-mana sotthanam | Akankha-mana sotthanam | ||

| Line 194: | Line 259: | ||

[[Atta]] [[samma]] [[panidhi]] ca | [[Atta]] [[samma]] [[panidhi]] ca | ||

Etam [[mangala]] muttamam. | Etam [[mangala]] muttamam. | ||

| − | Bahu saccanca sippanca | + | [[Bahu]] saccanca sippanca |

Vinayo ca susikkhito | Vinayo ca susikkhito | ||

Subhasita ca ya [[vaca]] | Subhasita ca ya [[vaca]] | ||

| Line 206: | Line 271: | ||

Anavajjani kammani | Anavajjani kammani | ||

Etam [[mangala]] muttamam | Etam [[mangala]] muttamam | ||

| − | [[Arati]] virati papa | + | [[Arati]] [[virati]] [[papa]] |

Majja-pana ca sannamo | Majja-pana ca sannamo | ||

Appa-mado ca [[dhammesu]] | Appa-mado ca [[dhammesu]] | ||

| Line 218: | Line 283: | ||

Many [[deities]] and [[humans]], yearning after good, | Many [[deities]] and [[humans]], yearning after good, | ||

| − | have pondered on [[Blessings]]. Pray, tell me the Supreme [[Blessings]]. Not to follow or associate with the [[foolish]], to associate with the [[wise]], and {{Wiki|honor}} those who are [[worthy]] of {{Wiki|honor}}. This is the Supreme [[Blessing]]. To reside in a suitable locality, to have done [[meritorious]] [[actions]] in the {{Wiki|past}}, and to have set oneself on the right course This is the Supreme [[Blessing]] Vast-learning, perfect handicraft, a highly trained [[discipline]] and [[pleasant]] [[speech]]. | + | have pondered on [[Blessings]]. Pray, tell me the Supreme [[Blessings]]. Not to follow or associate with the [[foolish]], to associate with the [[wise]], and {{Wiki|honor}} those who are [[worthy]] of {{Wiki|honor}}. This is the Supreme [[Blessing]]. To reside in a suitable locality, to have done [[meritorious]] [[actions]] in the {{Wiki|past}}, and to have set oneself on the right course This is the Supreme [[Blessing]] Vast-learning, {{Wiki|perfect}} handicraft, a highly trained [[discipline]] and [[pleasant]] [[speech]]. |

| + | |||

This is the Supreme [[Blessing]]. The support of mother and father, the cherishing of spouse and children and [[peaceful]] occupations. This is the Supreme [[Blessings]]. Liberality, righteous conduct, the helping of relatives and [[blameless]] [[action]]. | This is the Supreme [[Blessing]]. The support of mother and father, the cherishing of spouse and children and [[peaceful]] occupations. This is the Supreme [[Blessings]]. Liberality, righteous conduct, the helping of relatives and [[blameless]] [[action]]. | ||

| Line 233: | Line 299: | ||

Putthassa [[loka]] dhammehi | Putthassa [[loka]] dhammehi | ||

[[Cittam]] [[yassa]] na kampati | [[Cittam]] [[yassa]] na kampati | ||

| − | Asokam virajam khemam | + | [[Asokam]] [[virajam]] [[khemam]] |

Etam [[mangala]] muttamam | Etam [[mangala]] muttamam | ||

Eta-disani katvana | Eta-disani katvana | ||

| Line 253: | Line 319: | ||

* Resources: | * Resources: | ||

| − | Snelling, John (1991). The [[Buddhist]] Handbook. Rochester, VT: Inner [[Traditions]]. [[Rahula]], Walpola (1959). What the [[Buddha]] Taught. NY: Grove Press. Gard, Richard (1962). [[Buddhism]]. NY: George Braziller. The {{Wiki|Encyclopedia}} of Eastern [[Philosophy]] and [[Religion]] (1994). Boston: Shambhala. The Encyclopaedia Britannica CD (1998). {{Wiki|Chicago}}: Encyclopaedia Britannica. Access in | + | [[Snelling, John]] (1991). The [[Buddhist]] Handbook. Rochester, VT: Inner [[Traditions]]. [[Rahula]], [[Walpola]] (1959). What the [[Buddha]] [[Taught]]. NY: Grove Press. Gard, Richard (1962). [[Buddhism]]. NY: George Braziller. The {{Wiki|Encyclopedia}} of Eastern [[Philosophy]] and [[Religion]] (1994). Boston: Shambhala. [[The Encyclopaedia Britannica]] CD (1998). {{Wiki|Chicago}}: [[Encyclopaedia Britannica]]. [[Access in Insight]]: [[Gateways to Theravada Buddhism]]. (world.std.com/~metta/index.html) |

The [[Four Noble Truths]] * | The [[Four Noble Truths]] * | ||

| Line 263: | Line 329: | ||

1. [[Suffering]] is perhaps the most common translation for the [[Sanskrit]] [[word]] [[duhkha]], which can also be translated as imperfect, stressful, or filled with anguish. | 1. [[Suffering]] is perhaps the most common translation for the [[Sanskrit]] [[word]] [[duhkha]], which can also be translated as imperfect, stressful, or filled with anguish. | ||

| − | Contributing to the anguish is [[anitya]] – the fact that all things are [[impermanent]], including living things like ourselves. Furthermore, there is the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[anatman]] – literally, "no [[soul]]". [[Anatman]] means that all things are interconnected and [[interdependent]], so that no thing – including ourselves – has a separate [[existence]]. 2. [[Attachment]] is a common translation for the [[word]] [[trishna]], which literally means [[thirst]] and is also translated as [[desire]], [[clinging]], [[greed]], [[craving]], or [[lust]]. Because we and the [[world]] are imperfect, [[impermanent]], and not separate, we are forever "[[clinging]]" to things, each other, and ourselves, in a mistaken [[effort]] at {{Wiki|permanence}}. Besides [[trishna]], there is [[dvesha]], which means avoidance or [[hatred]]. [[Hatred]] is its own kind of [[clinging]]. | + | |

| + | Contributing to the anguish is [[anitya]] – the fact that all things are [[impermanent]], [[including]] living things like ourselves. Furthermore, there is the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[anatman]] – literally, "no [[soul]]". [[Anatman]] means that all things are interconnected and [[interdependent]], so that no thing – [[including]] ourselves – has a separate [[existence]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. [[Attachment]] is a common translation for the [[word]] [[trishna]], which literally means [[thirst]] and is also translated as [[desire]], [[clinging]], [[greed]], [[craving]], or [[lust]]. Because we and the [[world]] are imperfect, [[impermanent]], and not separate, we are forever "[[clinging]]" to things, each other, and ourselves, in a mistaken [[effort]] at {{Wiki|permanence}}. Besides [[trishna]], there is [[dvesha]], which means avoidance or [[hatred]]. [[Hatred]] is its [[own]] kind of [[clinging]]. | ||

And finally there is [[avidya]], [[ignorance]] or the refusal to see. Not fully [[understanding]] the [[impermanence]] of things is what leads us to [[cling]] in the first place. | And finally there is [[avidya]], [[ignorance]] or the refusal to see. Not fully [[understanding]] the [[impermanence]] of things is what leads us to [[cling]] in the first place. | ||

| − | 3. Perhaps the most misunderstood term in [[Buddhism]] is the one which refers to the [[overcoming]] of [[attachment]]: [[nirvana]]. It literally means "blowing out," but is often [[thought]] to refer to either a [[Buddhist]] [[heaven]] or complete [[nothingness]]. Actually, it refers to the [[letting go]] of [[clinging]], [[hatred]], and [[ignorance]], and the full [[acceptance]] of imperfection, [[impermanence]], and interconnectedness. 4. And then there is the [[path]], called [[dharma]]. [[Buddha]] called it the [[middle way]], which is understood as meaning the [[middle way]] between such competing [[philosophies]] as {{Wiki|materialism}} and {{Wiki|idealism}}, or {{Wiki|hedonism}} and [[asceticism]]. This [[path]], this [[middle way]], is elaborated as the [[eightfold path]]. | + | |

| + | 3. Perhaps the most misunderstood term in [[Buddhism]] is the one which refers to the [[overcoming]] of [[attachment]]: [[nirvana]]. It literally means "blowing out," but is often [[thought]] to refer to either a [[Buddhist]] [[heaven]] or complete [[nothingness]]. Actually, it refers to the [[letting go]] of [[clinging]], [[hatred]], and [[ignorance]], and the full [[acceptance]] of imperfection, [[impermanence]], and interconnectedness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4. And then there is the [[path]], called [[dharma]]. [[Buddha]] called it the [[middle way]], which is understood as meaning the [[middle way]] between such competing [[philosophies]] as {{Wiki|materialism}} and {{Wiki|idealism}}, or {{Wiki|hedonism}} and [[asceticism]]. This [[path]], this [[middle way]], is elaborated as the [[eightfold path]]. | ||

| + | |||

* quotations adapted from The [[Anguttara Nikaya]] 3.65, [[Soma Thera]] Trans., emphases added. | * quotations adapted from The [[Anguttara Nikaya]] 3.65, [[Soma Thera]] Trans., emphases added. | ||

The [[Eightfold Path]] | The [[Eightfold Path]] | ||

| − | 1. [[Right view]] is the true [[understanding]] of the [[four noble truths]]. 2. [[Right aspiration]] is the true [[desire]] to free oneself from [[attachment]], [[ignorance]], and hatefulness. These two are referred to as [[prajña]], or [[wisdom]]. 3. [[Right speech]] involves abstaining from lying, gossiping, or hurtful talk. 4. [[Right action]] involves abstaining from hurtful behaviors, such as killing, [[stealing]], and careless {{Wiki|sex}}. 5. [[Right livelihood]] means making your living in such a way as to avoid [[dishonesty]] and hurting others, including [[animals]]. | + | 1. [[Right view]] is the true [[understanding]] of the [[four noble truths]]. |

| − | These three are refered to as [[shila]], or [[morality]]. 6. [[Right effort]] is a matter of exerting oneself in regards to the content of one's [[mind]]: Bad qualities should be abandoned and prevented from [[arising]] again; Good qualities should be enacted and nurtured. | + | |