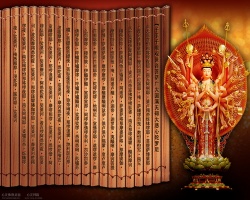

The Shurangama Sutra With Commentary by the Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua: Volume 1

The Shurangama Sutra

With Commentary by the Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua

Volume 1

Contents

- 1 Exhortation to Protect and Propagate

- 2 CHAPTER 1: The Ten Doors of Discrimination

- 2.1 The General Explanation of the Title

- 2.2 Causes and Conditions for the Arising of the Teaching

- 2.3 The Division and The Vehicle

- 2.4 The Depth of the Meaning and Principle

- 2.5 The Teaching Substance

- 2.6 Individuals Able to Receive the Teaching

- 2.7 Similarities, Differences and Determination of Time

- 3 CHAPTER 2: The History of the Transmission and Translation

- 4 CHAPTER 3: The Testimony of Faith

- 5 CHAPTER 4: Ananda’s Fall

- 6 CHAPTER 5: The Way to Shamatha

- 7 CHAPTER 6: Ananda Repents and Seeks the Truth

- 8 Continue Reading

- 9 Source

Exhortation to Protect and Propagate

Within Buddhism, there are very many important sutras. However, the most important Sutra is the Shurangama Sutra. If there are places which have the Shurangama Sutra, then the Proper Dharma dwells in the world. If there is no Shurangama Sutra, then the Dharma Ending Age appears. Therefore, we Buddhist disciples, each and every one, must bring our strength, must bring our blood, and must bring our sweat to protect the Shurangama Sutra. In the Sutra of the Ultimate Extinction of the Dharma, it says very, very clearly that in the Dharma Ending Age, the Shurangama Sutra is the first to disappear, and the rest of the sutras disappear after it. If the Shurangama Sutra does not disappear, then the Proper Dharma Age is present. Because of that, we Buddhist disciples must use our lives to protect the Shurangama Sutra, must use vows and resolution to protect the Shurangama Sutra, and cause the Shurangama Sutra to be known far and wide, reaching every nook and cranny, reaching into each and every dust-mote, reaching out to the exhaustion of empty space and of the Dharma Realm. If we can do that, then there will be a time of Proper Dharma radiating great light.

Why would the Shurangama Sutra be destroyed? It is because it is too true. The Shurangama Sutra is the Buddha’s true body. The Shurangama Sutra is the Buddha’s sharira. The Shurangama Sutra is the Buddha’s true and actual stupa and shrine. Therefore, because the Shurangama Sutra is so true, all the demon kings use all kinds of methods to destroy the Shurangama Sutra. They begin by starting rumors, saying that the Shurangama Sutra is phony. Why do they say the Shurangama Sutra is phony? It is because the Shurangama Sutra speaks too truly, especially in the sections on The Four Decisive Deeds, the Twenty-five Sages Describing Perfect Penetration, and the States of the Fifty Skandha Demons. Those of off-center persuasions and externally-oriented ways, weird demons and strange freaks, are unable to stand it. Consequently there are a good many senseless people who claim that the Shurangama Sutra is a forgery.

Now, the principles set forth in the Shurangama Sutra are on the one hand proper, and on the other in accord with principle, and the weird demons and strange freaks, those in various cults and sects, all cannot hide away their forms. Most senseless people, in particular unwise scholars and garbage-collecting professors “Tread upon the holy writ.” With their extremely scant and partial understanding, they are confused and unclear, lacking real erudition and true and actual wisdom. That is why they falsely criticize. We who study the Buddhadharma should very deeply be aware of these circumstances. Therefore, wherever we go, we should bring up the Shurangama Sutra. Wherever we go, we should propagate the Shurangama Sutra. Wherever we go, we should introduce the Shurangama Sutra to people. Why is that? It is because we wish to cause the Proper Dharma long to dwell in the world.

If the Shurangama Sutra is regarded as true, then there is no problem. To verify its truth, let me say that if the Shurangama Sutra were phony, then I would willingly fall into the hells forever through all eternity - for being unable to recognize the Buddhadharma - for mistaking the false for true. If the Shurangama Sutra is true, then life after life in every time I make the vow to propagate the Great Dharma of the Shurangama, that I shall in every time and every place propagate the true principles of the Shurangama.

Everyone should pay attention to the following point. How could the Shurangama Sutra not have been spoken by the Buddha? No one else could have spoken the Shurangama Sutra. And so I hope that all those people who make senseless accusations will wake up fast and stop creating the causes for suffering in the Hell of Pulling Out Tongues. No matter who the scholar is, no matter what country students of the Buddhadharma are from, all should quickly mend their ways, admit their mistakes, and manage to change. There is no greater good than that. I can then say that all who look at the Shurangama Sutra, all who listen to the Shurangama Sutra, and all who investigate the Shurangama Sutra, will very quickly accomplish Buddhahood.

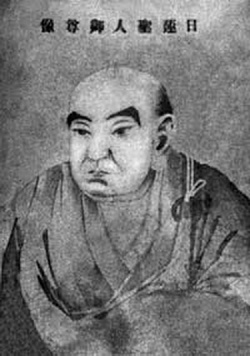

Composed by

Gold Mountain Shramana Tripitaka Master Hua

CHAPTER 1: The Ten Doors of Discrimination

The Sutra of the Foremost Shurangama at the Great Buddha’s Summit Concerning the Tathagata’s Secret Cause of Cultivation, His Certification to the Complete Meaning and all Bodhisattvas’ Myriad Practices.

Commentary:

These words are the complete title of the sutra. All but the word “sutra” are the specific designation which differentiates this sutra from others. The word “sutra” is the general designation for all the discourses of the Buddha.

The sutra titles in the tripitaka are divided into seven classes, which are more broadly divided into three kinds of single titles, three kinds of double titles, and complete titles.

The three kinds of single titles are:

1. Sutra titles that refer only to people. The Buddha Speaks the Amitabha Sutra is an example of this kind. The “Buddha” and “Amitabha” are both people; only people are named in this title. 2. Sutra titles that refer only to dharmas. The Maha-Parinirvana Sutra is an example. “Nirvana” is the dharma of non-production and non-extinction. 3. Sutra titles that contain only analogies. The title Brahma Net Sutra refers to the analogy, discussed in that sutra, of the circular curtain of netting of the Great Brahma King.

The three kinds of double titles are:

4. Sutra titles that refer both to people and to dharmas. The title Sutra of Manjushri’s Questions on Prajna indicates that Manjushri, a person, requests prajna, a dharma. 5. Sutra titles that refer both to people and to analogies. In the title Sutra of the Tathagata’s Lion’s Roar, the “Tathagata” is a person, and the "Lion’s Roar” is an analogy for the Buddha’s speaking of dharma. 6. Sutra titles that refer both to dharmas and to analogies. An example is the Wonderful Dharma Lotus Flower Sutra. “Wonderful Dharma” is the dharma, and "Lotus Flower” is the analogy.

The complete titles are:

7. Sutra titles that refer to people, to dharmas, and to analogies. The Buddha’s Universal Great Means Expansive Flower Adornment Sutra is an example. “Great” and “Universal” refer to dharmas, the “Buddha” is a person, and “Flower Adornment” is an analogy, in which the myriad practices that lead to enlightenment are said to be flowers that adorn the unsurpassed and virtuous attainment of enlightenment.

Every sutra title belongs to one of these seven classes, and everyone who lectures sutras should be able to explain them. If you do not understand these seven, how can you explain sutras for others? How can you teach others to become enlightened when you yourself have not awakened? You should not be like people who decide to call themselves dharma masters after reading a book or two, despite the fact that they can’t explain even one of the seven The Ten Doors of Discrimination 3 types of sutra titles or the fivefold mysterious meanings or a single door of the ten doors of discrimination. That is truly a case of premature exuberance. By speaking sutras and lecturing dharma without having reached a true understanding of them, these people send most of their listeners to the hells, and they themselves fall, too. Once in the hells, neither they nor their followers know how they got there. How pitiful! Only after reaching a genuine understanding and gaining genuine wisdom in the study of the Buddhadharma can one teach and transform living beings without making mistakes.

To explain the inexhaustible principles contained in the Shurangama Sutra, I will use the ten doors of discrimination of the Xian Shou (“Worthy Leader”) school rather than the fivefold mysterious meanings of the Tian Tai (“Heavenly Vista”) school. The Xian Shou and the Tian Tai are two great schools of Buddhism in China. Some dharma masters who lecture sutras have studied only one of the two schools, and so their explanations do not always reach the level of “perfect penetration without obstruction.”

The ten doors of discrimination of the Xian Shou school are:

- The general explanation of the title;

- The causes and conditions for the arising of the teaching;

- The division in which the sutra is included and the vehicle to which it belongs;

- The examination of the depth of the meaning and the principle;

- The expression of the teaching-substance;

- The identification of the appropriate individuals able to receive the teaching;

- The similarities and differences between the principle and its implications;

- The determination of the time;

- The history of the transmission and translation;

- The specific explanation of the meaning of the text.

The General Explanation of the Title

The Sutra of the Foremost Shurangama at the Great Buddha’s Summit Concerning the Tathagata’s Secret Cause of Cultivation, His Certification to the Complete Meaning and all Bodhisattvas’ Myriad Practices is the complete name of this sutra.

The word Great has four aspects and refers to a great cause, a great meaning, a great practice, and a great fruition.

The great cause is a Secret Cause. It differs from other causes in that ordinary people do not know of it; adherents of externalist religions do not understand it; and those of the two vehicles, sound-hearers and pratyekabuddhas, have not awakened to it. Thus it is great.

The great meaning is the Complete Meaning: the culmination of one’s Cultivation of the Way leading to Certification.

The great practice includes all the Bodhisattvas’ Myriad Practices.

The great result is the Foremost Shurangama. Because of these four kinds of greatness, the specific title begins with the word da “great.”

Buddha comes from a Sanskrit word that was transliterated into Chinese as fo tuo ye and subsequently abbreviated to fo. Although many people think the word fo is Chinese for Buddha, it is in fact only the first syllable of the full transliteration of the Sanskrit for Buddha. Buddha means “enlightened,” “awakened.” There are three kinds of enlightenment: enlightenment of self, enlightenment of others, and the perfection of enlightened practice.

The Buddha is enlightened. His state of being is different from that known to ordinary, unenlightened people. To be enlightened oneself is not enough, however. One must also enlighten others. The enlightenment of others involves thinking of ways to cause everyone else to become enlightened.

Within the enlightenment of self and the enlightenment of others there are various stages and myriad distinctions. There are, for instance, small enlightenments, which are not complete, and there is great enlightenment, which is total. The Buddha has by himself realized great enlightenment, and he also causes others to obtain great enlightenment.

When one has perfected both the enlightenment of self and the enlightenment of others, one attains the perfection of enlightenment and practice.

The Buddha has perfected the three kinds of enlightenment and so is adorned with myriad kinds of virtuous practices.

The three enlightenments perfected,

The myriad virtues complete:

Thus is he called the Buddha.

Someone may wonder why people believe in the Buddha. It is because we ourselves are Buddhas. That is, fundamentally we are Buddhas, but at present we are confused and unable to attain certification as Buddhas. The reason I say we are basically Buddhas is that the Buddha himself said: “All living beings have the nature; all can become Buddhas. It is only because of polluted thinking and attachments that they are unable to attain certification.” The polluted thoughts of living beings shift to the north, south, east, and west, above, and below. They suddenly pierce the heavens, suddenly drill into the earth. They reach to every conceivable place and their number is incalculable. Do you know how many polluted thoughts you have in a single day? If you do, you are a Bodhisattva. If not, you are still an ordinary person.

People become attached to possessions and constantly make distinctions of “me” and “mine.” They are unable to put aside material objects or physical pleasures. “That is my airplane.” “This is my car, the very latest model, you know.” One is attached to whatever one possesses. Men have masculine attachments, women have feminine attachments; good people have the attachments of good people; bad people have the attachments of bad people. No matter what the attachments are, those who have them cannot let them go. They keep grabbing, taking, and hanging on, getting more and more attached. The process is endless. Pleasures such as good food, a fine home, exciting entertainment, and the like are usually considered beneficial, but it isn’t certain that they are. Although you may not realize it, it is that very craving for pleasure that prevents your realization of Buddhahood. So the Buddha said, “It is only because of polluted thinking and attachments that living beings are unable to realize Buddhahood.”

In the Shurangama Sutra the Buddha said, “Bodhi is the ceasing of the mad mind.” The mad mind is explained as the false egocentric mind, the mind fond of status, the mind full of vain hopes and illusions, the mind that looks down on others and cannot see beyond its own achievements and intelligence. Even someone who is really ugly will consider himself to be very beautiful. Such strong attachments as these are dissolved when the mad mind is made to cease. That ceasing is Bodhi. It is an awakening to the Way; it is an enlightenment that is a first step toward the realization of Buddhahood. If you can cause the mad mind to cease, then you are well on your way.

Of the three kinds of enlightenment, the arhats’ and pratyekabuddhas’ enlightenment of self distinguishes them from ordinary, unenlightened people. Pratyekabuddhas awaken to the Way by cultivating the twelve links of conditioned causation. Arhats awaken to the Way by cultivating the dharma-door of the four sagely truths. Bodhisattvas differ from arhats and pratyekabuddhas in that they resolve to enlighten and to benefit others.

Ultimately, the arhats, the pratyekabuddhas, and the Bodhisattvas are simply people who have cultivated to the point of realization. How many people are we speaking of? We could be speaking of one person who cultivates to become first an arhat, then a pratyekabuddha, and then a Bodhisattva by means of the six paramitas and the myriad practices; such a person embodies all three levels.

Someone else, however, may cultivate to the level of arhatship, and then not want to go on. Once he himself has understood, such a person says: “I myself have already become enlightened. I understand. I can ignore everyone else.” He is a selfish person. He comes to a halt at the accomplishment of arhatship and it does not occur to him to continue down the path to pratyekabuddha-hood. Others continue to pratyekabuddhahood but do not consider progressing further. So one can say they are one person or one can say they are three people.

A Bodhisattva, however - one who enlightens himself and others . cultivates the six paramitas and the magnificence of the myriad practices, and he can continue to progress until he reaches the perfection of the Bodhisattva Way. That stage is said to be the perfection of enlightenment and practice; it is the realization of Buddhahood. The Buddha’s state of perfect enlightenment and practice distinguishes him from the Bodhisattva.

These three kinds of enlightenment can be discussed at length. When one practices them, many distinctions appear; within realizations are further realizations; within distinctions are further distinctions. The process is extremely complex.

The Summit is the highest point. The crown of the head is its summit; above that is heaven. It is sometimes said of people that “the top of the head touches heaven and the feet touch the earth”; such people are indomitable. Together, the words “Crown of the Great Buddha” refer to the top of the great Buddha’s head.

How big is the great Buddha? “The size of a six-foot-high Buddha-image?” you wonder.

No, a Buddha-image is like a mere drop in the ocean, or one fine mote of dust in a world-system. There is nothing greater than the great Buddha. He is great and yet not great. That is true greatness.

”Who is he?” you ask.

He is the Buddha who pervades all places. There is no place where he is and no place where he is not. No matter where you say he is, he is not there. Wherever you say he is not, he is there. What size would you say he is? There is no way to calculate how great he is, and so he is truly great - so great that he is beyond greatness.

”How can one be beyond greatness?”

No greatness can compare to his; his greatness is the most great.

”Who is he then?”

The great Buddha.

”Who is this great Buddha?”

He is you, and he is me.

”But I am not that great. And as far as I can tell, neither are you. How can you say he is you and me?” you ask. “How can you talk about it like this?”

If he did not have any connection with you and me, it would not be necessary to discuss him.

”How am I that great?” you ask.

The Buddha-nature is great, and it is inherent in us all. Just that is the incomparably great Buddha.

Now we are not only speaking of the great Buddha, we are referring to the crown of his head: his summit. And the great Buddha’s summit refers to the appearance of yet another great Buddha.

”How big is that Buddha?” you ask.

That Buddha is invisible. He is referred to in the verse that we recite before reciting the Shurangama Mantra:

The transformation atop the invisible summit

poured forth splendorous light

and proclaimed this spiritual mantra.

What is invisible can be said not to exist. How can one refer to the existence of a great Buddha when he cannot even be seen?

What cannot be seen is truly great. If it weren’t so big as to be invisible, why do you suppose you couldn’t see it?

”Little things are invisible, not big ones.”

Really? The sky is big, but can you see all of it? No! The earth is vast, but can you see its entire surface? No. What is truly great cannot be seen.

The great Buddha’s “invisible summit emits a light.”

”How great is the light?”

Think it over. Could a great Buddha emit a small light? Naturally the light he emits is so great it illuminates all places.

”Does it shine on me?”

It has shone on you all along.

”Then why am I not aware of it?”

Do you want to know of it?

When the mind is pure

the moon appears in the water.

When the thoughts are settled

the sky is without a cloud.

If your mind is extremely pure, the Buddha’s light will shine on you and illumine your mind like the moonlight deeply penetrating clear water. If your mind is impure, it is like a puddle of muddy water through which no light can pass. The mind in samadhi is like a cloudless sky, a state that is inexpressibly wonderful. If you can truly purify your mind, then you can obtain the strength of the Shurangama Samadhi.

Tathagata is a Sanskrit word; it means “Thus Come One.” There is nothing which is not “thus,” and nothing which is not “come.” “Thus” refers to the basic substance of the Buddhadharma, and “come” refers to the function of the Buddhadharma. “Thus” refers to a state of unmoving suchness. “Come” means to return and yet not return. It is said,

Thus, thus unmoving,

Come and come again,

Come and yet not come.

”Did he go?”

No.

”Did he come?”

No.

Therefore, it says in the Vajra Sutra that the Tathagata does not come from anywhere, nor does he go anywhere. He does not go to you nor does he come to me, yet he is right there with you and right here with me.

Tathagata is one of the ten names of the Buddha. Originally every Buddha had ten thousand names. In time these ten thousand names were reduced to one thousand because people got confused trying to remember them all. For a while every Buddha had a thousand names, but people still couldn’t remember so many, so they were again reduced to one hundred names. Every Buddha had a hundred different names and living beings had a hard time remembering them, so they were shortened again to ten, which are:

- Tathagata;

- One Worthy of Offerings;

- One of Proper and Universal Knowledge;

- One Perfect in Clarity and Practice;

- Well Gone One;

- One Who Understands the World;

- Unsurpassed One;

- Great Regulator;

- Teacher of Gods and People;

- Buddha, World Honored One.

All Buddhas have these ten names. The first, “Tathagata,” indicates that he has traveled the path as it truly is, and has come to realize proper enlightenment, that is, he has accomplished Buddhahood. The second, “One Worthy of Offerings,” indicates that he is worthy of receiving the offerings of gods and people.

The Secret Cause is the basic substance of samadhi power inherent in everyone. It is called “secret” rather than “manifest” because, although it is fundamentally complete in every person without exception, not everyone is aware of it. And so it is a secret. The secret is the basic substance of the Tathagata’s samadhi-power and in turn it is the basic substance of the samadhi-power of all living beings. The only difference is that living beings haven’t uncovered it, and so for them it remains a secret.

Cultivation, His Certification to the Complete Meaning. The secret cause must be cultivated and certified. Although investigation of dhyana and mindfulness of the Buddha are both means of cultivation, the cultivation referred to here is exclusively that of investigating dhyana. Through exclusive cultivation of dhyana one can be certified to and obtain the complete meaning, which is just no-meaning.

”Is that to say it is meaningless?”

The complete meaning is a complete certification to and realization of all worldly and world-transcending dharmas. There is no further dharma that can be cultivated, no further dharma that one can be certified as having attained. Great Master Yong Jia’s “Song of Enlightenment” speaks of the complete meaning:

Have you not seen the person of the Way,

who is beyond all learning

And, in leisure does nothing?

He neither casts out false thoughts

nor seeks reality.

The person of the Way does not do anything at all. He does not cast out false thoughts because he has already gotten rid of them. Only one who is not fully rid of them still needs to cast them out. The person of the Way does not seek after truth because he has already obtained it. Only those who have not obtained it need to seek it. These lines speak of the complete meaning.

The complete meaning, which is certified to, is also said to be “complete” because the principles spoken by the Buddha are so complete that an exhaustive study of them would reach to the end of all “meaning.” When one has exhausted all the principles that the Buddha spoke, then they do not exist; the meaning is complete. An incomplete meaning still has “meaning” left in it. The complete meaning is without any “meaning” at all. It is pure. When it is reached, it is the secret cause, the basic substance of proper samadhi. Reaching the basic substance, you cultivate and are certified to the complete meaning. If you do not cultivate you cannot attain the realm of the complete meaning, the great meaning which encompasses all meanings.

”But you said the complete meaning does not exist,” you say.

Yes, but that very non-existence is true existence. Relative existence is not true existence. When you have been certified as having understood the complete meaning, there are no further meanings for you to understand. You have arrived at the ultimate point.

”What is the ultimate accomplishment?”

It is the state of Buddhahood. But if you wish to reach the state of Buddhahood, you must continue to practice the Bodhisattva Way. Therefore, the title speaks of all the Bodhisattvas’ Myriad Practices. “All” can refer to the incalculable number of Bodhisattva’s practices. In general there are fifty-five Bodhisattva stages, which will be explained in detail later in the text. They include the ten faiths; the ten dwellings; the ten practices; the ten transferences; the four aiding practices; the ten grounds; and equal enlightenment, which comes before the wonderful enlightenment of Buddhahood. At each position are millions of Bodhisattvas. The fifty-five stages do not refer to a mere fifty-five Bodhisattvas, but rather to fifty-five levels through which limitless Bodhisattvas pass.

The “myriad practices” are the numerous ways in which Bodhisattvas cultivate. There are said to be 84,000 dharma-doors, but the title simply refers to them as “myriad practices.” In addition to their myriad practices, Bodhisattvas also cultivate the six paramitas - also called the six perfections.

"Paramita,” a Sanskrit word, literally means “arrived at the other shore.” It means to completely finish whatever you do. If you decide to become a Buddha, then the realization of Buddhahood is paramita. If you want to go to a university and get a Ph.D., obtaining the degree is paramita. If you’re hungry and want to eat, then to get full is paramita. If you’re sleepy, then to lie down and go to sleep is paramita. The Sanskrit word “paramita” is transliterated into Chinese as bo luo mi. Bo luo is Chinese for pineapple, and mi means honey. So the fruit of paramita is said to be sweeter than the pineapple.

Bodhisattvas cultivate the six paramitas. They are:

There are three kinds of giving: the giving of wealth, the giving of dharma, and the giving of fearlessness.

As to wealth: although money is one of the things people love most, it is also the dirtiest thing in the world. Just consider how many hands it passes through and how many germs it gathers. In Buddhism, money is considered unclean. First of all, its source is often unclean. It may have been stolen or embezzled.

”I’ve earned every penny of my money,” someone may complain. ”It’s clean!”

Even if your money comes from legitimate sources, you still can’t deny that the money itself is filthy and covered with germs. Even so, everyone still likes it. A lot of people spit on their fingers when they count money. Then they pass it back and forth, making it highly suspect as a carrier of infectious diseases. But in spite of its filth, no one is afraid of getting too much money. If you gave someone all the money in America, he would not think it was too much. But when you have a lot of money, you also have a lot of problems. You can’t get to sleep at night. You are kept busy figuring out where to put it. Since money keeps you so preoccupied, it is basically not a good thing. But even though it is not a good thing, most people love it and cannot give it up. One who can give away money practices the paramita of giving and is cultivating the Bodhisattva Way.

It is not easy for people to give. Their hearts are the junction of yin and yang, the battleground of reason and desire. For instance, someone sees someone else in bitter straits without a bit of food and, being a principled person, he decides to give the poor person a dollar. He reaches into his pocket, but suddenly his desire seizes him and he starts to have second thoughts. “Wait a minute. I can’t give him that dollar. It’s the last bit of change I’ve got. If I give it away, I won’t have any money for the bus and I’ll have to walk. I can’t do it.” His first impulse was to be generous to someone else, but it was followed immediately by a second thought: his own welfare. So he puts the money back in his pocket and doesn’t give it away. That’s the way it goes. It happens the same way on a large scale as it does on a small scale, all the way from a penny to a million dollars. The first thought is to give, the second thought concerns oneself. The giving of wealth is not easy. Some people even go so far as to think, “I’d be stupid to give my money to you. Why don’t you give yours to me?” It is easy to talk about giving, but when the time comes to do it, it is difficult.

Ever since I was young, I haven’t known how to count. Whenever I got some money, I gave it away. If I had one dollar, I gave that, and if I had two dollars, I gave them both away. I didn’t want money. Most people would consider my behavior very stupid, because I didn’t know how to help myself out. I only knew how to help others.

By benefiting others one brings forth the heart of a Bodhisattva, and those who bring forth the heart of a Bodhisattva benefit others rather than themselves. They say, “It’s all right if I have to suffer and endure distress, but I don’t want others to suffer.” Bodhisattvas always benefit others by practicing good conduct without bothering to figure out if they take a loss.

Some people spend all their time making sure they get a bargain. When they set out to buy something, they do a lot of comparison shopping until they come up with the best buy. But what they end up buying turns out to be cheap in more ways than one - things made of the “latest material” wrought from scientific experiments, things which look handsome enough but which break as soon as they are used. Although such people think they’re getting a good deal, in the end they take a loss. Instead of indulging in such calculated selfish behavior, you should work for the good of others.

The lecturing of sutras and explaining of dharma are the giving of dharma. It is said:

Of all the kinds of offerings

The gift of dharma is the highest.

The money you give can be counted, but the gift of dharma can’t be reckoned. If someone comes to a sutra lecture and hears something that causes him to become enlightened - to genuinely understand - can you imagine how great the merit derived from such a gift would be? Because the gift of a sentence of dharma can cause people to realize Buddhahood, it is the highest kind of giving.

The giving of fearlessness takes place, for example, when you bring calm to the victims of robbery or fire or any other catastrophe that causes them to be terrified or panic-stricken. You can calm them and comfort them by saying something like, “Don.t be afraid. No matter what the problem is, it can eventually be resolved.”

The second paramita practiced by Bodhisattvas is keeping moral precepts. This refers to the precepts and rules, which are one of the most important aspects of the Buddha’s teachings.

What are precepts?

Precepts are the rules of moral conduct that Buddhist disciples follow. The precepts stop evil and guard against mistakes. When you maintain precepts, you don’t indulge in any bad actions, but instead you conduct yourself properly and you offer up your good conduct to the Buddha.

How many kinds of precepts are there?

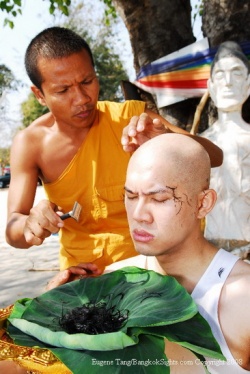

Laypeople who have taken refuge with the Triple Jewel - the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha - and who wish to make progress should take the five precepts. The five are not to kill, not to steal, not to commit sexual misconduct, not to lie, and not to take intoxicants. One vows to follow these rules for the rest of one’s life. After receiving the five precepts, laypeople can make further progress by taking the eight precepts. Beyond the eight precepts are the ten precepts of a shramanera (novice). After receiving the shramanera precepts, to become fully-ordained - to become one who has left the home-life - one can take the two hundred fifty precepts of a bhikshu (monk) or the three hundred forty-eight precepts of a bhikshuni (nun). There are also the ten major and forty-eight minor Bodhisattva precepts. The first ten are called “major” because one cannot repent and reform for violation of any of these ten. If one violates the minor precepts, it is still possible to change one’s faults and begin anew.

When the Buddha was about to enter nirvana, his disciple Ananda asked him four questions, one of which was this: “When the Buddha was in the world, he was our master; after the Buddha enters nirvana, who will be our master?”

The Buddha told him, “After I enter nirvana, you should take the precepts as master.” He was indicating that people who leave the home-life - all bhikshus and bhikshunis - should take the precepts as master.

Laypeople who seek to receive precepts should certainly seek them from one who has left the home-life. When the precepts are transmitted, the precept-substance must be bestowed upon the recipient by a bhikshu. According to the Buddha’s precepts, bhikshunis cannot transmit precepts.

It is absolutely essential for people who want to cultivate the Way to receive precepts. If you can guard the pure precept-substance, then you are as beautiful as a gleaming pearl. Vinaya Master Dao Xuan (“Proclaimer of the Way”), who lived on Zhong Nan mountain during the Tang dynasty, held the precepts so well that gods made offerings of food to him. The virtue of the precepts is very great. If you study the Buddhadharma without receiving the precepts, you will be a leaky bottle. To keep the precepts is to patch the leaks. The human body has outflows. It leaks. If you maintain the precepts for a long time, eventually there will be no outflows.

This Shurangama dharma assembly, in which the sutra is now being explained, offers a combination of study and practice. The schedule is strenuous, from 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. daily, much more rigorous than regular school - but this is a school for ending birth and death. It is a school of complementary practice and understanding. From the study of the Shurangama Sutra we derive understanding, and we practice by investigating dhyana. Through the combination of practice and understanding we can stride forward over solid ground and get the job done without carelessness or negligence. Through your efforts, you may solve the problem of birth and death and obtain extremely great benefit.

An example will help to illustrate the value of combining understanding with practice. A blind man and a cripple lived together in a family compound. There were several other people living with them and helping them out. One day, however, everyone else went out - fishing, shopping, doing the sorts of things people like to do. The blind man and the cripple were the only ones left at home. On that particular day a fire broke out in the house. The blind man couldn’t see and had no way to get out. The cripple could see, but he didn’t have any legs. What a predicament they were in! Both of them were certainly going to burn to death.

At that time a good and wise advisor gave them some advice. “You two can avoid dying. You can get out of this burning house. How? Cripple, let the blind man use your eyes. Blind man, let the cripple use your legs.” They followed his advice. Did the cripple gouge out his eyes and stick them in the sockets of the blind man? Without a surgeon such a method would surely fail. To put the blind man’s legs on the cripple without a physician would also be difficult. What did they do?

They made the best of the situation. The cripple climbed on the blind man’s back and told the blind man where to walk. “Go left, go right, go straight ahead.” The blind man had legs and, although he couldn’t see, he could hear the cripple’s instructions. Thanks to the timely advice, the two managed to save themselves.

When you hear this, don’t mistakenly think that I am calling you blind or crippled. It is not you who are blind or you who are crippled. I am blind and crippled. But having understood the principle involved, I have spoken the analogy, which is not speaking of you or me and yet is speaking of you and me.

No one should be arrogant. Don’t reflect on your singular understanding or the greatness of your wisdom. Why haven’t you realized Buddhahood? It is because you are too arrogant. “I have so much knowledge,” you think, but whatever you learn obstructs you. If you have a lot of knowledge, you are burdened with the obstruction of knowledge. If you have a lot of ability, your ability obstructs you so that you are unable to realize the Way. We should get rid of our thoughts of you, me, and him. Let the thoughts settle. Relax. Purify them. Empty your belly.

”What for?”

Then you can fill your belly with the wonderful flavor of clarified butter, the unsurpassed wonderful dharma. Once there was a young woman, a Ph.D. candidate, who admitted that her mind was full of garbage. Now we’ll use her words and say, throw out the “garbage” from your mind, and then you can listen to sutras. Then each thing you hear will unfold into a thousand understandings.

The third paramita of the Bodhisattva is patience. There are three kinds: patience with production; patience with dharmas; and patience with the non-production of dharmas.

The fourth paramita is vigor. To be vigorous is to continually advance and never retreat. An example of extreme vigor is given in the Wonderful Dharma Lotus Flower Sutra in the Chapter on the Past Deeds of Medicine King Bodhisattva. This Bodhisattva wrapped his body in cotton, saturated it with fragrant oils, went before the Buddhas, and burned his body as an offering.

”Why did he do that?” you ask.

Because he felt the Buddhas’ kindness was so sublime, so profound, and so great that there was just no way to repay it.

Therefore, he used his own body, heart, nature, and life as an offering to the Buddhas.

”How long did his body burn?” you wonder.

For an extremely long time. There is no way to calculate for how long it burned.

When the Great Master Zhi Yi (“Wise One”), third patriarch of the Tian Tai school, read the Chapter on the Past Deeds of Medicine King Bodhisattva, he entered samadhi when he came to the passage that reads: “This is true vigor. This is a true offering of dharma.” Within samadhi he saw that the assembly at Vulture Peak, where the Dharma Flower Sutra was spoken by the Buddha, was still there and had not yet adjourned.

Master Zhi Yi saw that Shakyamuni Buddha was still there speaking dharma, turning the great dharma wheel, teaching and transforming living beings. Thereupon Great Master Zhi Yi entered the Dharma Flower samadhi and obtained the once-revolving dharani. After experiencing this he withdrew from samadhi. By means of the great wisdom he had gained, he established and systematized the Tian Tai school. This response was evoked by the inconceivable merit and virtue of Medicine King Bodhisattva’s vigor when he burned his body as an offering to the Buddhas.

Most people will react by saying, “If plucking out a single hair of my head would benefit the entire world, I still wouldn’t do it.” That’s because they only know how to benefit themselves and not how to benefit others. They can’t be called vigorous.

The fifth paramita is dhyana concentration, also called dhyana samadhi. There are four dhyanas and eight samadhis. The nine successive stages of samadhi are discussed in the text of the Shurangama Sutra, so they will not be dealt with in detail now. I will explain the four dhyanas briefly.

The first dhyana is called the “state of joy apart from production.” In the first dhyana, one’s pulse stops.

The second dhyana is called the “state of joy from achieving samadhi.” Here one’s samadhi is more solid than in the first dhyana. In the second dhyana one’s breath stops, but this does not mean death; it is instead another realm of consciousness. The outer breath ceases and an inner breath comes to life. Ordinary people can use only their external breath. If a person can breathe internally, he can avoid death. He can live as many years as he wants. However, one can live so long as to turn into a useless corpse-guarding ghost obsessed with the need to protect his “stinking skin-bag” of a body.

The third dhyana is called the “state of wonderful bliss detached from joy.” Most people who cultivate like to experience joy. However, the bliss experienced in the third dhyana, which is detached from joy, is extremely wonderful. In this dhyana, conscious thought ceases.

The fourth dhyana is called the “state of pure renunciation of thought.” Here all thoughts are abandoned. One can know what is happening in the heavens and among people. But one should not become attached to the experience. Entering the samadhi of the fourth dhyana represents only a first step in cultivating the Way. One should not think that accomplishing the fourth dhyana is a special attainment. It is just the first step toward realizing Buddhahood. It is not even the accomplishment of the first stage of arhatship.

The sixth paramita is prajna. Prajna is a Sanskrit word that may be translated as wisdom. Most people consider mundane intelligence to be wisdom. It is not. Intelligence is worldly knowledge such as that derived from the study of science, philosophy, and the like. “Wisdom” refers to the world-transcending wisdom that realizes Buddhahood. This is prajna. The word prajna is not translated because it contains many meanings and thus falls within the five kinds of terms not translated, which are:

- terms that are secret;

- terms that have many meanings;

- terms that refer to something not existing in the translator’s country;

- terms that traditionally have not been translated; and

- terms that are honorifics.

This list was first drawn up by Tripitaka Master Xuan Zang in the Tang dynasty.

There are three kinds of prajna:

- literary prajna;

- contemplative prajna;

- true-appearance prajna.

Literary prajna refers to the wisdom contained in the sutras. Contemplative prajna refers to the wisdom gained through returning the light and illumining within, through reversing the hearing to hear the self-nature. It arises when your eyes don’t gaze outside but look within. With the light of wisdom of contemplative investigation, you can illumine and break through all darkness within you. When that happens you become very clear and pure inside and are no longer burdened with filth. True-appearance prajna, the most wonderful inconceivable kind of prajna, is synonymous with the “complete meaning” of which the sutra speaks. The true appearance has no appearance, and yet there is nothing left without an appearance. If you say that it has no appearance, everything thereupon appears. Thus it is the true appearance. If you understand this, you are right next to the Buddha; you are but a step away.

The Vajra Sutra says, “All that has appearance is empty and false. If you see all appearances as no appearance, then you see the Tathagata.” Everything that has an appearance is false. If, while in the midst of appearances, you can understand that they have no appearance, then you see the Buddha. You understand the basic substance of the dharma and penetrate to the dharma’s source. To see the source of all dharmas is to see the Buddha.

uch an experience is easy to talk about, but difficult to attain. You can’t understand just by hearing lectures; you must think of a way to travel that road. For instance, one may say, “I’d like to travel to New York, but it’s so far away and flying is very expensive. I guess I won’t go.” However, if you never go, you’ll never know what New York is like. Realization of Buddhahood is the same way. On the one hand, you want to become a Buddha, but on the other hand, it’s such a long hard pull that it would take forever to get there. It’s just like looking at the sea and heaving a great sigh. “Studying the dharma is too difficult; I’ll find something easier to do.” If you take that attitude, you will never realize Buddhahood. If you don’t want to become a Buddha, then there’s nothing to talk about. But if you do then you must endure difficulties, because only through difficulty is ease attained. In China it is said, “If the winter’s cold did not pierce to the bone, how could the plum blossoms be so fragrant?” The extremely sweet-smelling plum blossom of China blooms in mid-winter. As a result of enduring the bitter cold, the blossoms have an exquisite fragrance.

Every living being is endowed with true-appearance prajna, but like the “secret cause” of this sutra, it is not yet manifest within them, and they are unaware of their own inheritance. We do not realize the prajna of our own nature, its inherent true-appearance, and so we are as if poverty-stricken within the dharma. Prajna is the wisdom we have always had. We should open this treasure-room of wisdom, and then our original face will appear. As long as we don’t know that we are endowed with true-appearance prajna, we carry an undiscovered gold mine inside us. To discover the gold mine is not enough, however. We have to use manpower to mine the gold before it can be used. The sutras tell us that the gold mine of prajna exists within each one of us, but unless we mine the gold, it’s not of much use to know about it. We must put in the work and vigorously resolve to cultivate. Then we can mine the prajna, and our inherent Buddha-nature will appear.

The Buddha said, “All living beings have the Buddha-nature and can realize Buddhahood.” But one cannot say, “The Buddha said I am a Buddha, so I am a Buddha even without cultivating.” This is to know the gold is there and yet not bother to dig it from the ground.

This has been a general explanation of the six paramitas of the Bodhisattva. Everyone can decide to be a Bodhisattva and cultivate the Bodhisattva’s practices. If you carry out the deeds of a Bodhisattva, then you are a Bodhisattva with an initial resolve. Bodhisattvas do not selfishly say, “Only I can become a Bodhisattva. You can’t be a Bodhisattva. You can’t compare to me.” Not only can everyone become a Bodhisattva; everyone can become a Buddha. I believe that everyone in this assembly will attain Buddhahood someday.

Foremost Shurangama. Shurangama is a Sanskrit word that means “the ultimate durability of all phenomena.” “All phenomena. refers to everything - all the mountains, rivers, the great earth, buildings, people, and things, as well as all creatures born from wombs, from eggs, from moisture, and by transformation. When one plumbs all things to their unchangeable source, one obtains the basic substance of samadhi, the samadhi of the “secret cause.” When one obtains the samadhi of the “secret cause,” one can then be certified as having attained the “complete meaning.” When one is certified as having attained the complete meaning, one then cultivates the six paramitas and the myriad practices of a Bodhisattva and thereby attains the “great practice.” When one has attained the great practice, one can then accomplish the samadhi of the ultimate durability of all things, which is the “great result”

The Great Buddha’s Summit, then, refers to the wonderful advantages of the four kinds of greatness: the great cause, the great meaning, the great practice, and the great result. They can also be called the wonderful cause, the wonderful meaning, the wonderful practice, and the wonderful result. However, “wonderful” doesn’t describe them completely, and so the word “great” is used.

”The ultimate durability of all phenomena” refers to samadhi. Without samadhi, the body and mind are distracted and do not work in harmony. You may decide to go south, but your legs refuse to obey; you end up walking north. Or you may want to do good deeds, but you lose control and somehow end up committing crimes instead. A lack of consistency or constancy in carrying things out is also evidence of a lack of samadhi. In studying the Shurangama Sutra everyone should be firm, sincere, and constant. You should firmly resolve, “I am determined to study until I understand the principles of the Shurangama Sutra.” You shouldn’t stop in the middle of the road and turn around to go back; you shouldn’t hit the drum to adjourn the meeting prematurely. Don’t draw the line when you’ve come only half way. Don’t say, “Ah, I’ve studied so many days and haven’t understood yet. This is extremely difficult material. I don’t think I’ll study it any more.”

With sincerity, you can study in earnest and can keep your mind on what you are doing. You are so delighted by study that all worries are forgotten. You study so industriously that you forget to eat. When you lie down at night to sleep no thoughts arise other than those of the doctrines in the sutra.

With constancy, you don’t study for a few days and then back out, feeling that studying the Buddhadharma is dry and uninteresting. You don’t decide to go play in the park or find some good entertainment. You don’t think up excuses: “There’s no practical value in studying this stuff. It’s antiquated in this scientific age,” and then run away. Without constancy, you lack ultimate durability.

With cultivation of these three - firmness, sincerity, and constancy - you can be “ultimately durable” and gain Samadhi-power. With samadhi-power, you will not be “turned by states”: you won’t be controlled by your environment. This is a general explanation of the specific title of this sutra

Sutra. To translate the Sanskrit word “sutra,” the Chinese used the character that means “to tally,” because a sutra tallies above with the principles of all Buddhas and below with the opportune circumstances for teaching all living beings.

”Sutra” is also defined as a “path,” for it can lead ordinary people to the position of Buddhahood. “Sutra” has four further meanings: stringing together, attracting, constant, and method. A sutra strings together the meanings within it, like beads strung on a thread. It attracts the beings for whom the teaching will be opportune. The sutras present the dharmas appropriate to the particular needs of beings, as medicine is prescribed to cure specific illnesses. The sutra is like a magnet and living beings are like the iron filings which are attracted to the magnet. The Shurangama Sutra is like a magnet, and so it is called “durable.” But the Shurangama Sutra is even stronger than a magnet. It can keep people from falling ever again. Thus it gathers in living beings so that they cannot possibly fall again into the realms of the hells, or turn into hungry ghosts, or change into animals. They are magnetized so that even if they want to run away they can’t. Even if they want to fall they won’t be able to. That’s how wonderful the sutras are! People come to listen to a sutra lecture and once they’ve heard they become magnetized. They hear one passage and they want to hear the next. “This makes sense!” they exclaim. “I like the flavor. It’s really sweet!” Sutras are said to be constant because from ancient times to the present day they have not changed. Not one word can be added or taken away. They are permanent and unchanging. The sutras are said to be methods, for they are revered by beings in the past, present, and future because they contain methods to cultivate the Way, realize Buddhahood, and teach and transform living beings.

The Buddhist canon is composed of twelve divisions. All twelve may be found within each sutra. The twelve divisions are:

- prose;

- reiterative verses;

- bestowal of predictions;

- causes and conditions;

- analogies;

- past events;

- present lives;

- broadening passages;

- previously non-existent dharma;

- unrequested dharma;

- interpolations;

- discussions.

The first of the twelve divisions consists of the prose sections of the sutras - in Chinese, literally the “long lines.” The second division, the reiterative verses, consists of verses that rephrase the meanings expressed in the prose sections of the sutras.

The third division is bestowal of predictions. In the sutra Shakyamuni Buddha may tell a Bodhisattva, “In such and such an age, you will become a Buddha. Your name will be such and such, your lifespan will be so long and in such and such a country you will teach living beings.” An example is Dipankara (“Burning Lamp”) Buddha’s bestowing the prediction of Buddhahood upon Shakyamuni Buddha. In a former life, on the cause-ground, Shakyamuni Buddha cultivated the Bodhisattva Way so sincerely in his search for the dharma that once he “spread out his hair to cover the mud.” Why did he do that? Once in a former life, when Shakyamuni Buddha was walking down a road, he noticed a bhikshu walking toward him. He didn’t know the bhikshu was actually a Buddha. The road that lay between them was muddy and full of puddles. “If that old bhikshu walks through all this water, he’s bound to get drenched,” thought the future Shakyamuni Buddha, and out of his respect for the Triple Jewel, the ascetic lay down in the mud and water. He used his body as a mat on top of the water and invited the old monk to walk on his body to cross the puddles. There was a small portion of the puddle still exposed, and fearing the old bhikshu would have to step in the mud, he loosened his hair and spread it out over the mud for the bhikshu to walk on.

Who would have guessed that the old bhikshu was a Buddha! The Buddha, whose name was Dipankara, was pleased to witness such a sincere offering and he said, “So it is, so it is, you are this way and I am also this way.” The first “so it is” meant: “You have now made an offering to me by lying down and allowing me to walk over the top of your body.” The second “so it is” meant “In the past, I was this way, too. I also cultivated the Bodhisattva Way.” His meaning was, “You are correct.” And then Dipankara Buddha gave him a prediction, saying, “In the future you will become a Buddha named Shakyamuni.” Why did Dipankara Buddha offer this prediction? Because he was moved by the sincerity of the future Shakyamuni Buddha’s heart, and so although he usually paid no attention to other people’s affairs, he took notice of this gesture and gave him a prediction of Buddhahood.

The fourth division of the sutra explains the causes and conditions that lie behind the speaking of various dharmas. In the fifth division, analogies are used to make clear the wonderful aspects of the Buddhadharma. In past events, the sixth division, the sutras relate events in the former lives of Shakyamuni Buddha or of various Bodhisattvas. Present lives, the seventh division, discusses events in Shakyamuni Buddha’s present life or in the present lives of various Bodhisattvas. Broadening dharma, the eighth division, refers to the universality of the dharma spoken. Previously non-existent dharma, the ninth division, refers to dharma that has never been spoken before. Without a request from anyone, the Buddha himself emits light, moves the earth, and speaks unrequested dharma, the tenth division. Interpolation, the eleventh division, refers to verses that express meanings that have no connection with the passages preceding or following. The twelfth division is discussions.

A verse says:

Prose and reiterations;

Interpolations;

Bestowal of predictions;

Unrequested dharma;

Causes and conditions;

Past lives; analogies;

Discussions; never been before;

This life; broadening passages

Make up twelve divisions;

The shastra of great wisdom

Explains them in roll thirty-three.

Each sutra has within it these twelve divisions. This is not to say that there are only twelve volumes in the Buddhist canon, but that every section of the sutra text falls under one of these divisions.

Causes and Conditions for the Arising of the Teaching

Teachings are the transmissions of a sage - a Buddha or Bodhisattva - in order to teach and transform living beings. The teaching arises from causes and conditions, and these come from living beings. If there were no living beings, there would be no Buddha. If there were no Buddha there would be no teaching. Therefore the teaching is established for the sake of living beings. The causes and conditions are the reasons for the teaching. They cause living beings to end birth and death. This is the reason Shakyamuni Buddha appeared in the world. The Dharma Flower Sutra says, “The Buddha appeared in the world because of the causes and conditions of one great matter.” What is this matter? It is the problem of everyone’s birth and death. Because people don’t understand why they are born and why they die, they continue to undergo birth and death. Shakyamuni Buddha appeared in the world to cause living beings to understand why they are born and why they die.

Where did you come from when you were born?

Where will you go after you die?

Once born into the world, living beings are busy all their lives finding places to live, clothes to wear, and food to eat. They become so preoccupied with pursuing food, clothing, and shelter that they have no time to solve the problem of birth and death. This is how ordinary people carry on. They say, “We must work hard and keep busy to get two meals, clothes, and a place to live.” Nobody is busy figuring out how to end birth and death. They don’t think about it. They don’t wonder, “Why did I come into this world? How did I get here? Where did I come from?”

When you meet someone, you say, “Where are you from? How long have you been here?” But people never ask these questions of themselves. They have forgotten where they came from, and they have forgotten where they are going. They forget to ask themselves, “Where am I going to go when I die?” It is just because people have forgotten to ask themselves this question that Shakyamuni Buddha came into this world to urge us to investigate the problem of birth and death.

The Dharma Flower Sutra says further that the Buddha appeared in the world to cause all living beings to give rise to the Buddha’s knowledge and vision; to display the Buddha’s knowledge and vision, to become enlightened to the Buddha’s knowledge and vision; and to enter the Buddha’s knowledge and vision. Originally all living beings inherently possess the Buddha’s knowledge and vision. Their wisdom is identical to the Buddha’s. But in a living being the wisdom is like the gold in the mine mentioned above. Before the mine is excavated the gold is not evident. Once you realize the existence of your inherent Buddha-nature, you can cultivate in accord with the dharma; you can excavate the mine and extract the pure gold that contains no slag or impurities.

”Where is our inherent Buddha-nature? Where is our inherent wisdom?”

The Buddha-nature is found within our afflictions. Everyone has afflictions and everyone has a Buddha-nature. In an ordinary person it is the afflictions, rather than the Buddha-nature, that are apparent. Afflictions are like ice. Our wisdom is like water. Our Buddha-nature is like moisture, which is present in both ice and water. So, too, the Buddha-nature is found within both wisdom and affliction. But while moisture is common to both ice and water, their physical properties differ. A small piece of ice is hard and can harm people if you hit them with it; in the same way you can injure people by giving rise to afflictions. But a small amount of water is harmless if you pour it over somebody; in the same way, a wise person, by the sound of his voice, can make people happy even when he’s scolding them. If you use your affliction to make trouble for others, your great ignorance will ignite as soon as you speak to them. In fact, you may upset someone so much that the two of you come to blows, and certainly someone will be injured.

People can return to the original source if they can change their afflictions into wisdom. The change is analogous to the melting of ice. You can’t say that the ice is not water, for the ice melts into water. You also can’t say that the water is not ice, for water can freeze into ice. Their common quality is their moisture. In the same way, no one can argue that living beings are not the Buddha or that the Buddha is not a living being. The Buddha belongs to living beings, and living beings belong to the Buddha. You should understand this doctrine. You need only change and melt the ice. This is to be useful to people.

I say that water can’t harm people; but someone may argue that everyone is aware of the danger of drowning and the danger brought by floods.

It is true that a lot of water can harm people; but in the analogy I referred to a small amount of water. If you want to come up with unreasonable objections, the possibilities are endless. You should grasp the meaning and not be obstructed by the particulars. Without faith your genuine wisdom won’t ever manifest. Genuine wisdom arises out of genuine stupidity. When the ice turns to water, there is wisdom; when the water freezes into ice, there is stupidity. Afflictions are nothing but stupidity. If you are thoroughly clear, then you are without afflictions.

In lecturing the sutras, I refer to principle. Don’t try to use specifics to criticize principles; the two are different. You should continue to listen, and when you have heard a lot of dharma you will understand. Having only heard a little, you are unable to put it together. “What is he talking about?” you wonder. “I don’t understand.” You’ve never heard it at all before; how could you understand? If you could understand the dharma without ever having heard it before, your wisdom would be truly exceptional. Perhaps you have heard it in the past; but this is the first time for you in this life. The first time you hear it, it seems familiar; but even then, hearing it is a gradual process. In the same way, if you meet someone for the first time, he may seem familiar to you, but it takes several meetings before you can easily recognize him.

Once you understand that your own nature is the Buddha-nature, you can change your afflictions into Bodhi. To realize Bodhi means to become enlightened: enlightened to the fact that you should not be attached to anything. If you have attachments, you cannot become enlightened.

A Bodhisattva is not the same as you. Although he has attachments, he is not enlightened. If you had no attachments, you’d be enlightened. A Bodhisattva is not enlightened because he doesn’t want to be enlightened. He wants to be together with living beings. But your thoughts are not the same as the attachments of a Bodhisattva, for he can’t forsake living beings and he sees everyone as good. For this reason he doesn’t want to be enlightened. One with the heart of a Bodhisattva wishes for the welfare of others and is unconcerned for himself. A Bodhisattva would willingly descend into the hells and undergo limitless sufferings if it would cause people to realize enlightenment. If there are good things to eat, he tastes a little bit and then gives the food to others. In the same way, he has already tasted a bit of the flavor of enlightenment and wants to give everyone a taste. To taste the flavor of enlightenment, you must sever your afflictions. When you are without afflictions and devoid of ignorance, wisdom comes forth and you become liberated. That is to give rise to the Buddha’s knowledge and vision.

Once you give rise to the Buddha’s knowledge and vision - once you’ve excavated the gold mine - then you need to display the Buddha’s knowledge and vision. You still need to work hard, just as it takes manpower to bring up the gold. First you must get rid of the dirt and then gradually you remove the gold from the sand. To display the Buddha’s knowledge and vision, you instruct living beings in how to be truly vigorous.

Displaying requires cultivation - sitting in meditation and investigating Chan every day, until one day, while you are sitting, your contemplation will suddenly penetrate through, and you will become enlightened. You will understand, “Oh, originally it was thus. Originally it was all just this way.” You will have truly solved the questions of human existence. This is to be enlightened to the Buddha’s knowledge and vision.

The Buddha’s knowledge and vision are not to be mistaken for the knowledge and vision of living beings. Living beings use their knowledge and vision to give rise to incessant false thoughts. Deep attachments cause them to become afflicted by the least impoliteness. “How can you be so mean to me?” you say. In fact, people will inevitably be good to you if you are truly good to them. It is not that people are not good to you but rather that you have not been good to them. If you understand this doctrine, then no one can be mean to you.

One hand claps,

but makes no sound

Only two hands clapping

can make a sound.

Everyone bows to the Buddha with utmost respect because the Buddha is truly good. This is why no one is not good to the Buddha.

”I don’t believe it,” someone may say. “Some people slander the Buddha.”

People who slander the Buddha can’t even be counted as people. They simply don’t understand how to be people and so they slander the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. They don’t understand the basic question of their own lives. If they knew how to be human, they wouldn’t slander the Triple Jewel.

We should enter the Buddha’s knowledge and vision once we are enlightened to them. This also takes work. You must work to understand and then you must work some more. You must return the light and illumine inwardly. When your light illumines your heart and you become truly wise, then you will have entered the Buddha’s knowledge and vision, with no duality, no difference. The Buddha spoke the sutras in order to cause beings to give rise to, to display, to become enlightened to, and to enter the Buddha’s knowledge and vision.

In general, these are the reasons that Shakyamuni Buddha, in over three hundred dharma assemblies held for over forty-nine years, spoke the sutras and taught the dharma in the world. With particular reference to the Shurangama Sutra, six causes and conditions lie behind its being spoken.

The first of these six is:

1.The dependence on erudition and the neglect of Samadhi-power.

T he Buddha’s disciple and cousin, Ananda, was very learned; he read widely and he was very knowledgeable. He followed the Buddha for several decades and could remember the dharma spoken at every dharma assembly. His memory was so keen that once he heard something, he never forgot it. Ananda didn’t have to force himself to remember, it came very naturally. Often, however, learned people force themselves to remember the principles they read in books and they come to rely upon their learning. “Look at me,” is their attitude, “I know more than all of you. I have Ph.D.’s in science, philosophy, and literature. Why, I have more than a hundred Ph.D.’s!” Although Ananda’s ability to learn came naturally, he also relied on it too much, and he neglected developing his samadhi-power. He thought samadhi was not important. “I know a lot of things and have wisdom. That’s sufficient. Samadhi-power isn’t important. It is said that through samadhi one develops wisdom, but I already have wisdom.” So he forgot about samadhi.

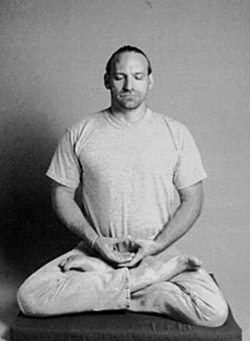

The Shurangama Sutra was spoken for Ananda’s sake, precisely because he didn’t have sufficient samadhi-power. He had not done the work of meditation required to develop it. When others were sitting investigating dhyana, Ananda would go read a book or write instead. The wonderful quality of the Shurangama Lecture and Cultivation Session, in which this sutra is being explained, is that it combines the actual practice of sitting in meditation with the understanding gained from the study of the sutra. You can practice meditation in accord with your new understanding. Through the application of effort, you can become enlightened. But it is essential both to develop samadhi and to acquire learning.

In other words, Ananda hadn’t cultivated true-appearance prajna; he thought he could realize Buddhahood through literary prajna alone. He thought that since he was the Buddha’s cousin, the Buddha, who had realized Buddhahood, would certainly help him realize Buddhahood, too. Thinking that it didn’t really matter whether he cultivated or not, he ended up wasting a lot of time.

One day, as the Shurangama Sutra relates, Ananda went out to receive alms by himself. He took his bowl and went from house to house. While walking alone on the road, he encountered the daughter of Matangi. Ananda was particularly handsome, and when Matangi’s daughter saw him, she was immediately attracted to him. But she didn’t know how to snare him. So she went back and told her mother, “You absolutely must get Ananda to marry me. If you don’t, I’ll die.”

Now the mother, Matangi, belonged to the religion of the Kapilas, the “tawny-haired,” and she cultivated this religion’s mantras and dharma-devices, which were extremely effective. Since Matangi really loved her daughter, she used a mantra of her sect - a mantra that they claimed had come from the Brahma Heaven - to confuse Ananda. Ananda didn’t have any Samadhi-power, so he couldn’t control himself. He followed the mantra and went to Matangi’s daughter’s house, where he was on the verge of breaking the precepts.

The first five precepts prohibit killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and the taking of intoxicants; and Ananda was about to break the precept against sexual misconduct. The Buddha knew about it as it was happening. Realizing his cousin was in trouble, he quickly spoke the Shurangama Mantra to break up the former Brahma Heaven mantra of the Kapila religion. Ananda’s confusion had made him as if drunk or as if he had taken dope - he was totally oblivious to everything. But when the Buddha recited the Shurangama Mantra, its power woke Ananda up from his confusion, and there he was wondering how he had gotten himself into such a situation.

He returned, knelt before the Buddha, and cried out in distress. “I have relied exclusively on erudition and have not perfected any strength in the Way. I haven’t any samadhi-power. Please, Buddha, tell me how the Buddhas of the ten directions have cultivated so they were able to obtain samadhi-power.” In reply the Buddha spoke the Shurangama Sutra. This was the first reason that it was spoken.

The second reason it was spoken was:

2. To warn about those with insane wisdom who cherish deviant thoughts.

There are many intelligent people in the world who, despite their intellectual ability, do not follow proper paths, but instead use their knowledge in ways that harm people. This is deviant thought. They harbor deviant thoughts and have no desire to put an end to them, because they think they are correct. They outsmart themselves and act in a very confused way. The sutra issues a warning about them.

There is a proverb that says:

Intelligence is helped by hidden virtue.

Hidden virtue leads you to enter the path of intelligence.

Those who do not practice hidden virtue,

but make use of intelligence alone,

Will be defeated by their own intelligence.

People are intelligent because in past lives they undertook virtuous practices. Perhaps they studied hard in past lives, or they read many Buddhist sutras. But intelligence is established by doing this good work in secret. It is “hidden virtue” that others do not see. Intelligence does not come to people who do a good deed and then strike the gong, beat the drum, and put an ad in the paper or on television saying, “I, so-and-so, have just now done something good.” Such a person may have done good deeds, but this is not hidden virtue. Good deeds that are done unknown to anyone are hidden virtue; they are genuine good deeds. So it is said:

Good done hoping others will notice it is not true good.

Evil done fearing others will discover it is great evil.

People who want the good they do to be known haven’t done genuine good; they’re just being greedy for a good reputation. The very greatest kind of evil is done secretly in the fear that people will find out.

Hidden virtue practiced in the past may endow us with intelligence, but if we don’t use our intelligence correctly, if we don’t practice hidden virtue and do good deeds, but instead do evil, our intelligence defeats us and we defeat our intelligence. It becomes merely a petty knowledge, a petty intelligence, not true intelligence.

For example, the great general Cao Cao of the Three Kingdoms period in China was extremely intelligent, but as deceptive as a ghost. But great Emperor Yao of China was said to have divine wisdom. Wise people are sometimes even called gods. But, one should not view gods too highly in the Buddhadharma. They do not hold a very high position. They are simply dharma protectors whose job is to protect the Triple Jewel of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

One of great good who falls will join the ranks of evil. If someone who does great evil recognizes it and changes, he can be considered a person of great good because he has had the courage to change. However, when someone who ordinarily does good deeds decides to do evil and cheat people because he doesn’t notice any particular response to his former conduct, he thereby becomes a very evil person since he is one who clearly knows what is right and intentionally does wrong.

A person with “insane wisdom” does upside-down things - improper things - and still feels he is correct. He may go so far as to commit murder and say: “If I hadn’t killed that man, he might have killed others. But because I have killed him, he won’t kill anyone else.” In truth, the victim was not a potential murderer at all, but the killer had a grudge against him. This is deviant thought. Someone basically in error makes up a rationale for his behavior; he makes up a fine story to avoid the judgment of the courts. Although he is wrong, he is very convincing and he wins his case. This is insane wisdom. The Shurangama Sutra warns people against making arguments based on deviant thoughts. It warns people who do this not to cherish deviant thoughts, not to be convinced that they are right, but to change their ways and to correct their thinking so they may return to the proper path, to proper thought.

The third reason for the speaking of the sutra is:

1. To point to the true mind and manifest the basic nature.

The Shurangama Sutra points directly to our mind so we may see our nature and realize Buddhahood.

”What is this mind?”

It is the true mind, which cannot be seen. The heart within your chest that you can see is merely the flesh-heart, the only function of which is to keep you alive. It is not the true mind. It certainly cannot lead you to genuine understanding. If the heart within your chest were the true mind, it should be able to accompany you when you die. However, a person’s body remains after death and the flesh heart is still within it. So the flesh heart is not your true mind. Your true mind is the Buddha nature.

”Where is the Buddha nature?”

It is “not outside or inside or in the middle.” The sutra text will explain this principle in great detail. The sutra will also explain the “ten instances of manifesting the seeing-nature,” that is, one’s true mind. This is the third reason the sutra was spoken: to point out the pure nature and bright substance of the eternally dwelling true mind, which neither comes nor goes, neither moves nor changes. It is the basic substance, without defilement; its nature is pure, its substance, bright.

The fourth reason the sutra was spoken is:

2. To display the samadhi of the nature and to exhort us to actual certification.

There are many dharma-doors in the cultivation of samadhi. Externalists also develop samadhis; but in cultivating samadhis, if one is off at the beginning even by a hair’s breadth, one will miss the mark in the end by a thousand miles. Therefore it is necessary to cultivate proper samadhi, and to avoid cultivating deviant samadhi. The samadhis cultivated by externalists are deviant samadhis, not proper samadhis. Because their samadhis are not the proper samadhi of the true nature, they will never achieve sagehood, no matter how long they cultivate. It is said:

When the nature is in samadhi,

demons are subdued and every day is blissful;

When false thoughts do not arise

everywhere is peaceful.

Why do people have demonic obstacles when they cultivate? Why do karmic obstacles arise? It is just because people’s natures lack samadhi. If the nature is in samadhi, all demons can be subdued.

There are many kinds of demons. This sutra explains fifty kinds of “skandha demons.” Actually there are many, many demons: heavenly demons, earth demons, human demons, ghost demons, and weird demons. Heavenly demons are the demon-kings in the heavens who come to disturb your dhyana concentration. Earth demons that dwell on the earth, human demons, ghost demons, weird demons, and strange creatures also all come to disturb your dhyana concentration.

”Why do they do this?”

Because before you attain Buddhahood you are a member of the demons’ family. When you decide to leave the family of demons, cultivate dhyana concentration, end birth and death, and break through the turning wheel, the demons are still fond of you. They love you and can’t let you go. Therefore they come to bother your spirit and disturb your dhyana concentration.

If you have no concentration-power, you can be turned by the demon-states and end up following them. If you have concentration- power, you won’t be turned. You will be “thus, thus unmoving / clear and eternally bright.” To be “thus, thus unmoving” is to have concentration power. To be “clear and eternally bright” is to have wisdom-power. With the combined powers of concentration and wisdom, no demon can move you. But if you have no concentration or wisdom-power, you will follow the demons and become their children and grandchildren. It is extremely dangerous.